Sacsahuaman

A skillful arrangement of several thousand colossal blocks rising in three tiers to 60 feet, located outside the city of Cuzco. Many of the finely cut, meticulously fitted stones weigh about 100 tons each. The largest single block is 9 feet thick, 10 feet wide, and 20 feet tall, with an estimated weight of nearly 200 tons.

According to conventional archaeological dogma, Sacsahuaman was raised as a fortress around 1438 a.d. by the Incas. But they only occupied the site long after it was built by an earlier people remembered as the Ayar-aucca, a race of “giants” who arrived in Peru as refugees from a cataclysmic flood. Sacsahuaman was used as a quarry by the Spanish throughout the 16th century to furnish construction material for churches and colonial palaces, so its original appearance and actual purposes were obscured. Even some mainstream archaeologists tend to believe the intentions of its creators were less military than ceremonial or spiritual.

The superb workmanship evidenced at Sacsahuaman is matched by the daunting tonnage of its blocks. Even with the aid of modern machinery, positioning them with equal precision and finesse would present severe challenges. Their cutting, moving, lifting, and fitting during pre-Columbian times seems far beyond the limited capabilities of any pre-industrial people. Modern experiments to replicate construction using the primitive tools and means supposedly available before the Europeans arrived invariably produce ludicrous results. Clearly, some unimaginable, lost technology was used by the Ancient Peruvians. Their Atlantean identity in the Ayar-aucca is underscored by Sacsahuaman’s uncanny resemblance to an underwater site in the Bahamas, a suspected outpost of Atlantis.

The Saga of Ninurta

A Sumerian epic describing the destruction of Atlantis: “From the mountain [Mount Atlas] there went forth the pernicious tooth [eruption] scurrying, and at his [Ninurta's] side the gods of his city cowered on the Earth.”

Sagara

In Japanese myth, a dragon-god of an undersea kingdom and possessor of a magical sword and a “pearl” able to cause catastrophic floods. Sagara appears to reference the sunken civilization of Mu.

Saka-duipa

Cited in the Sanskrit Suria Adanta as pre-deluge Atlantis, home of the sun-worshiping Megas, Atlantean priests or adepts who carried the esoteric principles and “magic” of their solar cult to India and other parts of the world.

Salinen Deluge Story

According to this California tribe, humanity perished in a world flood. Only a single diving bird survived. It dove to the bottom of the ocean and fetched up a beak-full of muck from the bottom of the sea. Seeing this performance, Eagle God descended from the sky to fashion a new race from the retrieved mud.

The Salinen myth describes the rebirth of mankind after its near-extinction in the Late Bronze Age catastrophe that destroyed Atlantis.

Samatumi-whooah

The Okanagons of British Columbia taught that their ancestors came from Samatumi-whooah, literally “White Man’s Island,” which sank in the midst of evil wars, drowning all its inhabitants, save a man and his woman. The Maryland Indians claimed that the whites were an ancient generation who, perishing in a great deluge, were reborn and had returned to claim their former holdings in America. Both traditions are tribal memories of the Atlantean war and flood described by Plato, with the addition of survivors arriving in the New World.

Samudranarayana

A temple standing on an embankment above the Gomati River where it flows into the Indian Ocean. Although the name of the sea-god Samudra, to which Samudranarayana has been dedicated, suggests the lost Pacific Motherland of Mu, the sacred structure’s circular design resembles the concentric layout of Atlantis, as described by Plato. Samudranarayana may have been a blending of both sunken civilizations.

Sa Na Duniya

An early king in Hausa oral tradition of Nigeria, head of the “Sea Peoples” who invaded around 1200 b.c., following the Great Flood which engulfed his former kingdom.

Saracura

“Water Hen,” a goddess who saved the ancestors of the Karaya and Ges Indians from a universal flood by leading them to the peak of a mountain at the center of the world. This deluge-myth suggests the Atlantean Navel of the World cult.

Schliemann, Paul

Described as either the grandson or great nephew of Heinrich Schliemann, the renowned discoverer of Troy and Mycenea. Paul Schliemann’s published article, “How I Discovered Atlantis, The Source of All Civilization,” appeared in a 1912 edition of the New York American. It claimed that Heinrich, while excavating Trojan ruins on the hill at Hissarlik, in Turkey, found a large bronze vase covered with a Phoenician inscription that read, “From King Cronos of Atlantis.” Paul promised readers that a topic fully explaining his discovery of Atlantis would be published shortly thereafter, but he was never heard from again.

Most skeptics and even Atlantologists believe the article was a hoax, if only because records exist of neither a grandson nor great nephew for Heinrich Schliemann named Paul. But some investigators point out that, if it were a hoax, no one appears to have benefited from it in any way. And Paul Schliemann’s disappearance may have been explained by his death as a soldier in World War I, which followed publication of his story by two years. They also cite some internal evidence he provided, such as the association of Cronos, the Greek Titan synonymous for the Atlantic Ocean, with Atlantis. In any case, until written verification of Paul Schliemann’s existence and fate comes to light, his New York American article remains a mystery.

Scomalt

The North American Okanaguas’ ancestral “Medicine Woman,” who ruled over “a lost island” at the time of the Deluge. In the Hopi version, she was called Tuwa’bontumsi.

Sea Peoples

In Egyptian, the Meshwesh or Hanebu. In 1190 b.c., they mounted a major invasion of the Nile Delta. After initial success, they were defeated and taken captive. The testimony of Sea People prisoners-of-war, recorded in the wall-texts of Pharaoh Ramses Ill’s Victory Temple at Medinet Habu, in West Thebes, showed them to be the same aggressors described in Plato’s account of Atlantis. The Greeks claimed their land was first civilized by the Pelasgians, a “sea people” from the Far West.

In North America, the Menomonie Indians of the Upper Great Lakes remember an alien race of white-skinned “Marine Men” or “Sea People,” who arrived from over the Atlantic Ocean long ago to “wound Earth Mother by extracting her shining bones,”—that is, they mined copper.

Sekhet-Aaru

The Egyptians’ realm of the dead, but also their ancestral homeland on an island in the Distant West, from which their forefathers arrived at the Nile Delta in the Tep Zepi, or “First Time,” at the start of dynastic civilization. On the other side of the world, the Aztecs believed their ancestors came from an island kingdom in the Distant East, called Aztlan. Both Sekhet-Aaru and Aztlan mean “Field of Reeds.” To the Egyptians and the Aztecs alike, reeds, employed as writing utensils, were symbolic of literacy and wisdom, implying that Sekhet-Aaru/Aztlan was a place of extraordinary learning.

Sekhmet

Egyptian goddess of fiery destruction credited in the wall texts of Medinet Habu with the destruction of Neteru (Atlantis). Sekhmet was actually identified with a threatening comet, “shooting-star,” or awesome celestial phenomenon of some kind.

Semu-Hor

In ancient Egyptian tradition, “The Followers of Horus,” they were culture-bearers who arrived at the Nile Delta from Sekhet-aaru, “the Field of Reeds,” their sunken homeland in the Distant West. The Semsu-Hor were survivors from the upheavals that beset Atlantis in the late fourth millennium b.c.

Sequana

Celtic goddess of the River Seine, who reestablished her chief shrine at or near Dijon after the destruction of Atlantis, which is specifically mentioned in her French folk tradition. Alternate versions describe Sequana as a princess who sailed to the Burgundian highlands directly from the Great Flood that drowned her distant island kingdom. Its name, Morois, compares with Murias, the sunken city from which the pre-Celtic Tuatha da Danann arrived in Ireland.

Traveling up the Seine, Sequana erected a stone temple near Dijon. In it she stored a sumptuous treasure—loot from lost Atlantis—in many secret chambers. After her death, she became a jealous river-goddess. There is, in fact, a megalithic center near Dijon made up of subterranean passage ways that are still sometimes searched for ancient treasure.

Sequana was reborn in the Sequani, a Celtic people who occupied territory between the Rhein, Rhone, and Saone Rivers. The Romans referred to the area as Maxima Sequanorum, known earlier as Sequana.

Seri Culture-Bearer Tradition

The “Come-From-Afar-Men” were revered by the Seri Indians of Tiburon Island as powerful but kindly sorcerers who arrived in a “long boat with a head like a snake” that ran aground and was ripped apart on a reef in the Gulf of California, “a long time ago, when God was a little boy.” Tall, with red or white hair, the “Come-From-Afar-Men” taught compassion and healing. They interbred with a local people, the Mayo, who still occasionally evidence anomalous Caucasian features. Until the 1920s, the Mayo expelled tribal members who married outside the group.

The Seri tradition appears to be a revealing folk memory of Lemurian priests shipwrecked on the shores of southern California.

Shan Hai Ching

Ancient Chinese cosmological account that describes a prehistoric catastrophe that occurred when the sky tipped suddenly, causing the Earth to tilt in the opposite direction. The resulting flood sent a vast kingdom to the bottom of the ocean.

Shasta

A volcanic California mountain described in several local American Indian myths as the only dry land to have survived a worldwide flood. Building a raft, Coyote-Man sailed over great expanses of water to arrive at its summit. There he ignited a signal fire that alerted other survivors, who gathered at Mount Shasta, from which they repopulated the Earth. Into modern times, mysterious lights sometimes seen on the mountaintop are associated with ceremonies of a “Lemurian brotherhood,” whose initiates allegedly perform rituals from the lost civilization. These lights, like that of the Indians’ flood hero, Coyote-Man, are probably electrical phenomena known to occur at the peaks of seismically active mountains bearing strong deposits of crystal. As earth tremors squeeze the mineral, it emits electrical discharges, similar to the piezeo-electrical effects of a crystal radio receiver.

The intensity of negative ions generated by this phenomenon can interface with the bio-circuitry of the human brain, inducing altered states of consciousness related to spiritual or shamanic experiences. Hence, the mystical character of Mount Shasta for Native Americans and modern visitors alike is not difficult to understand.

Shawnee Deluge Story

This American Indian tribe occupies much of southern Illinois, where massive stone walls atop precipitous bluffs form a broken chain, nearly 200 miles long, across the bottom part of the state from the Mississippi to Ohio Rivers. According to the Shawnee, these structures were built by immigrating giants who survived the Great Flood. An area of the Shawnee National Forest is still referred to as “Giant City” in memory of these ancient deluge immigrants. According to Shawnee tradition, this catastrophe killed every human being, save for a single, old woman. In despair at being alone in the world, she sadly molded clay dolls into anthropomorphic shapes to help her remember vanished mankind. Taking pity on her, the Great Spirit turned the clay figures into living men and women, and the Earth was repopulated. Hence, the Shawnee revere Old Grandmother as their ancestress.

The Shipwrecked Sailor

An Egyptian “tale” with strong Atlantean overtones, thought to date to an early dynastic epoch, but repeated and elaborated upon even in Ptolemaic times. An original papyrus of the story is in the possession of Russia’s Saint Petersburg Museum, and dates to the XX Dynasty, circa 1180 b.c. Significantly, this is the same period in which Egypt defended herself against the “Sea People” invasion. The final destruction of Atlantis is believed by investigators to have occurred in 1198 b.c.

The story of the shipwrecked sailor opens with a terrible storm, far out at sea. A freighter carrying miners is lost, and only one man clinging to some wreckage is eventually washed ashore at some distant island.

“Suddenly, I heard a thunderous noise,” he says. “I thought it must have been a great wave striking the beach. Trees swayed and the Earth shook.” These stirrings announced the arrival of the Serpent King, a huge, bearded creature overlaid with scales of gold and lapis lazuli. He carefully picked up the hapless sailor in his great jaws and carried him to his “resting place.” There he told the man about “this island in the middle of the sea, an Isle of the Blest, where nothing is lacking, and which is filled with all good things, a far country, unknown to men.” After a four-month stay, the king loads his guest down with gifts. “But when you leave this place,” he warns, “you will never see this island again, because it will be covered by the waves.”

Interestingly, the Serpent King referred to his island kingdom as “Punt.” This is the same ambiguous land generations of pharaohs visited with commercial expeditions, returning with rich trade goods, until the late 13th-century b.c. destruction of Atlantis, with which it has been identified. Moreover, the Serpent King’s island is seismic (“the Earth shook”), “in the middle of the sea,” and “a far country unknown to men.” He calls his kingdom “the Isle of the Blest,” the same epitaph used by Greek and Roman writers to characterize Atlantis. His description of this island kingdom as rich in natural abundance (“where nothing is lacking and which is filled with all good things”) is reminiscent of Plato’s version of Atlantis: “The island itself provided much of what was required by them for the uses of life. All these that sacred isle lying beneath the sun brought forth fair and wondrous in infinite abundance” (Kritias). In fact, the Serpent King himself leaves no doubt of his island’s Atlantean identity: “You will never see this island again, because it will be covered by the waves.”

The Serpent King’s portrayal as a fabulous beast is transparently symbolic of a powerful monarch. The Pyramid Texts read, “Thou, Osiris, art great in thy name of the Great Green [the ocean]. Lo, thou art round as the circle that encircles the Hanebu.” Howey commented, “Osiris was thus the serpent [dragon] that lying in the ocean, encircled the world”—that is, had power over it (164). The Hanebu were the “Sea Peoples” of Atlantis reported by the scribes of Ramses III in the wall-texts of his Victory Temple at Medinet Habu. The Serpent King’s appearance points up his royal provenance. The beard was an emblem of sovereign authority. Even Queen Hatshepsut had to wear a false beard during her reign. And his “scales” of gold and lapis lazuli represented his raiment. The sailor’s transportation to the Serpent King’s “resting place,” (the palace) in the “great jaws”—the edged weapons of his guards—is a metaphor for the power of command.

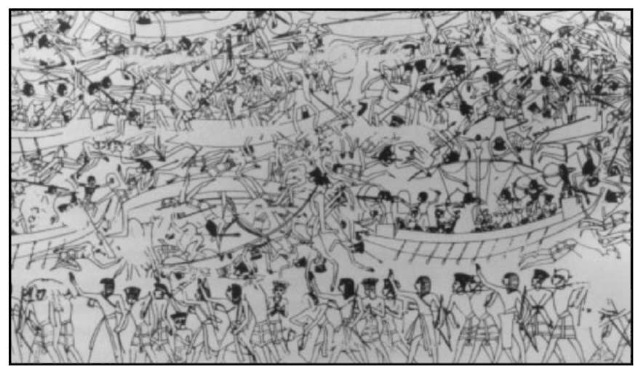

The ancient Egyptian artist commissioned to portray the war fought by his Pharaoh against invading Atlanteans conveyed something of the campaign’s vast scope and carnage, as reflected in this partial tracing from Medinet Habu.

These mythic images shed light on the Feathered Serpent, the legendary founding-father of Mesoamerican Civilization from across the Sunrise Sea. The Quiche Mayas’ foremost culture hero was Votan, from Valum, the Kingdom of Serpents. Both Coatlicue and Mama Ocllo, the leading ladies of Aztec and Inca legend, respectively, belonged to “the race of serpents.” Amuraca, the Bochica Indians’ first chief, means “Serpent King.” Like the Egyptian Serpent King, Amuraca once ruled over an island in the midst of the sea.

The Serpent King tells his shipwrecked guest about “a young girl on whom the fire from heaven fell and burnt her to ashes.” Why this curious aside should be included in the tale, if not as an allusion to the celestial impact responsible for the Atlantean catastrophe, is otherwise inexplicable.