Pacata-Mu

This huge and important pre-Inca religious center featured a complex labyrinth the size of four football fields surrounded by high walls of mud brick. The maze was apparently the scene of large-scale ritual activities, judging from the sacrificed remains of llamas and curious tiny squares of exquisitely woven cloth of no apparent utilitarian value. Such squares are still used, however, by North American aboriginals of the southwestern states to contain religious offerings of tobacco.

Pacata-Mu’s name and location in northern coastal Peru, on a promontory overlooking the Pacific Ocean, underscore its Lemurian origins.

Painted Cave

A site located on the North American west coast above Los Angeles. Its interior is decorated with dozens of red, white, and black pictoglyphs and astronomical depictions created by the Chumash Indians before their extinction in the late 19th-century. Painted Cave and all such illustrated sites were revered by Chumash shamans as the spiritual centers of their ancestors, who named a number of islands and settlement after the lost Pacific civilization of Mu, such as Pismu, modern Pismo beach, at San Nicholas Island, formerly Limu.

Palatkwapi

An Atlantic island that the Patki Indians told of, on which a sorceress lived a very long time ago. Her evil powers so menaced the world, the gods drowned her by sinking Palatkwapi. The resulting tsunami destroyed almost all living things on Earth, but a few human survivors reached the eastern shores of North America to become the founders of the Patki tribe.

Pali-uli

Legendary island of plenty and joy from which the Hawaiian ancestors escaped before it was destroyed in a terrible deluge. (See Hiva, Kahiki)

Pan

The Algonkian Atlantis. Its flood myth tells how:

…the Earth rocked to and fro, as a ship and sea, and the rains fell in torrents, and loud thunderings came up from beneath the floor of the world. And the vortex of the Earth closed in from the extreme, and, lo, the Earth was broken! A mighty land was cut loose from its fastenings, and the fires of the Earth came forth in flames and clouds with loud roarings. And again the vortex of the Earth is about on all sides, and the land sank down beneath the waters, to rise no more. The Algonkian version takes a line from Plato’s account: “In the same day, the gates of heaven and Earth were opened” (Churchward, 74). Pan is likewise identified with Atlantis in various Puranas of India. An Atlantean saga was retold in the Mexican Toltec tradition of Pantitlan.

Pandyan

Indian version of Mu.

Partholon

In The Topic of Invasions, a Medieval collection of Celtic and pre-Celtic oral traditions, he was the tragic leader of a lost sea people who sought refuge in Ireland. They were preceded by the Fomorach, who stubbornly opposed them. Partholon nonetheless succeeded in conquering much of the country, dividing its land into five districts, after defeating Cichol Gricenchos, the Fomorach king. Unfortunately, a plague so decimated the Family of Partholon, they were unable to defend themselves against renewed Fomorach resistance, so they evacuated Ireland and disappeared into myth.

Coming as they did some time after the Fomorach, “Partholon’s people” were probably immigrants from the geologic upheavals that beset Atlantis during the late third millennium b.c. Certainly, Partholon’s division of Ireland into five districts is the same kind of Atlantean geopolitics found in Plato’s Kritias.

Patkinya-Mu

The Hopi “Dwelling-on-Water Clan” whose members anciently crossed the Great Sea from the west. The flood refugees in North America, known as the Patki, or “Water People,” were met by Massau, a native guide, who directed them to the Southwest, where they could live in peace. All the Patki were able to save from their sunken homeland was a stone tablet broken at one corner. Massau prophesied that some day in the distant future a lost white brother, Pahana, would deliver the absent fragment, thereby signalling the beginning of a new age, when brotherhood would again prevail on Earth. Over the millennia, the stone was in the special care of the Fire Clan. When their representative gave it to a Conquistador in the 1500s, the Spaniard did not reciprocate as expected, so the Hopi continue to wait for Pahana. It is remarkably similar to Pakeha, a name bestowed by New Zealand natives on the first modern Europeans they met in the late 18th century. It derives from the Pakahakeha, the Maui version of an ancestral sea people, a white-skinned race from the sunken kingdom of Haiviki.

Patulan-Pa-Civan

A Quiche Maya variant of Atlantis. The Popol Vuh, a Yucatan cosmology, tells how “the Old Men…came from the other part of ocean, from where the sun rises, a place called Patulan-Pa-Civan.”

Payetome

A South American version of the “Feathered Serpent” or “Sea Foam” known to various Indian tribes of coastal Brazil. Distantly removed from the high civilizations of both Mesoamerica and the Andes, their tradition of a tall, white-skinned, light-eyed, fair-haired, and fair-bearded man arriving in the ancient past is folkish evidence for a culturally formative event these less sophisticated natives shared with the materially superior Mayas and Incas. The aboriginal Brazilians remember Payetome as the leader of a “tribe” of fellow immigrants, whose kingdom across the ocean was obliterated by a world flood. He was a gentle and wise man who taught medicine, agriculture and magic.

Pelasgians, or Pelasgi

In Greek tradition, a “sea people” who entered the Peloponnesus and the islands of the Eastern Mediterranean about four thousand years ago. They were the forefathers of the Achaean or Bronze Age inhabitants of Greece, named after their leader, Pelasgus, remembered as the First Man. A third-century b.c. vase painting portrays him emerging from the jaws of a serpent, while the goddess Athena stands ready to welcome him. In Aztec sacred art, Mesoamerica’s white-skinned culture-bearer, Quetzalcoatl, the “Feathered Serpent,” identically appears out of a snake’s mouth. In both instances, the serpent signified their hero’s arrival by sea. Pelasgus was believed to have been born between the fangs of Ophion, a primeval, metaphorical snake personifying the undulating ocean. Athena’s presence in the vase painting signifies the destiny of Pelasgus as the first civilizer of Greece.

Notable mariners, the Pelasgians came from the Far West, where they conquered Western and Northern Europe, just as Plato’s Atlanteans were said to have done, previous to their arrival in the Eastern Mediterranean. The pre-Greek “Linear A” written language of ancient Crete and the enigmatic Phaistos Disk are attributed to the Pelasgians. The disk is a baked clay plate found at the Cretan city of Phaistos, inscribed in a spiral pattern on both sides with unknown hieroglyphs. According to the first-century b.c. Greek geographer Diodorus Siculus, writing was introduced by the Pelasgians, and the mathematical genius Pythagoras was supposed to have been directly descended from them.

Waves of immigrants from Atlantis who entered the eastern Mediterranean during the geologic upheavals of the late third millennium b.c. were referred to by the Greeks as “Pelasgians.”

Pelota

A Basque ball game virtually identical to a Maya version, and cited by various Atlantologists (Muck, von Salomon, and others) to establish a cultural correspondence with Atlantis. Both Basque and Maya oral traditions are rich in references to the lost civilization.

Peng Sha

In Chinese myth, a large and resplendent island kingdom in the East, far over the sea, where spiritual powers reached their fulfillment. Among the adepts were sorcerers who mastered human levitation. Peng Sha was sometimes identified with the original homeland of Kuan-Yin Mu.

Phaeacia

In the Odyssey, Calypso gives the hero sailing directions to Phaeacia. Her instructions are according to another set of Atlantises, the Pleiades, and indicate a currently blank area of the Atlantic Ocean between Madeira and the Strait of Gibraltar. Atlantologists have discovered no less than 56 details that Homer’s Phaeacia shares with Plato’s Atlantis, leaving little doubt that the same island is indicated by both names.

The king of Phaeacia was Alkynous, a male derivative of the Pleiadian Atlantis, Alkyone. His capital was Scherie, virtually a mirror-image of Atlantis, including bronze-sheeted walls, interconnecting causeways, and a centrally located Temple of Poseidon, from whom he and his royal family claimed direct descent, just as mentioned in Kritias. Like the Atlantean kings, he sacrificed bulls to the sea-god. The island of Phaeacia was described as remote, mountainous, agriculturally prosperous, with a year-round temperate climate and abundant natural springs of hot and cold water. Its inhabitants were rich in copper and gold, exceptional mariners, manufacturers of purple dye for royal robes, and the descendants of Titans—the same details Plato accords to the Atlanteans.

Some Phaeacian names cited by Homer, in addition to King Alkynous, are identifiably Atlantean, such as Eurymedusa (see “Gorgons”) and Amphialus, Plato’s Atlantean king, Ampheres. Interestingly, Homer identifies himself as the Phaeacian bard, Demodocus, “whom the Muse loved above all others, though she mingled good and evil in her gift, stealing his sight, but granting him sweetness of song.” Investigators have interpreted Homer’s one and only appearance in either the Iliad or the Odyssey as a self-declaration of his Atlantean descent.

His Phaeacian description of Atlantis, while so like Plato’s in numerous particulars, is more detailed. Readers learn about the sumptuous palace and its surrounding garden, together with information about the Atlanteans themselves,to an extent not covered in the Dialogues. Their counterpart is the Odyssey, and, combined, they flesh out an in-depth portrait of Atlantis during its cultural zenith.

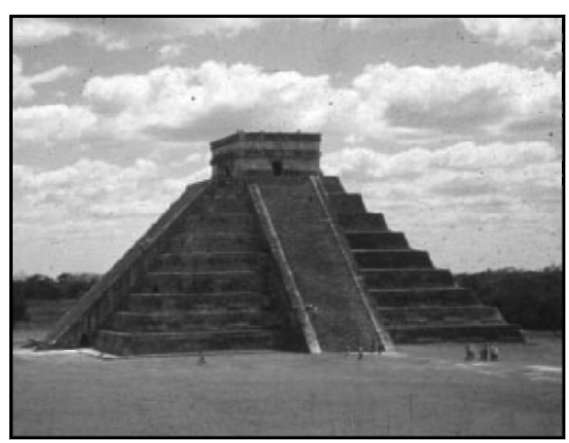

The uppermost chamber of Chichen Itza’s Pyramid of Kukulcan is decorated with the faded images of four bearded men holding up representations of the sky, like so many Atlases.