Oak

The tree sacred to Atlas; its branches, like his arms, supported the heavens. The oak’s association with Atlas implies a primeval tree cult or pillar cult, a memory of it surviving in Kritias, Plato’s Atlantis account, when he described a ceremonial column at the very midpoint of the Temple of Poseidon, itself located at the center of Atlantis. The Atlanteans’ oldest, most hallowed laws were inscribed on its exterior, and sacrificial bull’s blood was shed over it by all 10 kings of Atlantis in that civilization’s premiere ritual.

Oannes

Described in Babylonian myth as a bearded man dressed in a fish-like gown who brought “The Tablets of Civilization” from his kingdom in the sea to the Near East. The Maya preserved an almost identical tradition of Oa-ana, “he who has his residence in the water.” Like his Mesopotamian counterpart, he was considered an early culture-bearer who sparked Mesoamerican Civilization after arriving with great wisdom from across the Atlantic Ocean. Both Oannes and Oa-ana cross-reference Atlanteans landing on both sides of the world.

Obatala

Along the Gold Coast of West Africa, fronting the Atlantic Ocean, there are several accounts of the Atlantean deluge among the Yoruba people. They tell how Olokun, the sea-god, became angry with the sins of men, and sought to cause their extinction by instigating a massive flood that would drown the whole world. Many kingdoms perished in the ocean, until a giant hero, Obatala, standing in the midst of the waters and through his juju, or magical powers, bound Olokun in seven chains. The seas no longer swelled over the land, and humanity was saved.

In this West African version of the flood, Obatala is the Yoruba version of the Greco-Atlantean Atlas: Oba denotes kingship, while atala means “white.” Yoruba priests wear only white robes while worshipping him, and images of the god are offered only white food. Among these sacrifices are white kola and goats, recalling the Atlantean goat cults known to the ancient Canary Islanders, off the coast of northwest Africa, and the Iberian Basque. Obatala’s chief title is “King of Whiteness,” because he is revered as the white-skinned “Ancient Ruler” and “Father” of the Yoruba race by a native woman, Oduduwa. Like Atlas, Obatala was a giant in the middle of the sea, and the “seven chains” which signal the end of the Deluge may coincide with the seven Pleiades, associated throughout much of world myth with the Flood’s conclusion. Directly across the Atlantic Ocean, in the west, the Aztec version of Atlantis—Aztlan—was referred to as the “White Island.” In the opposite direction, in the east, Hindu traditions in India described ancestral origins from Attala, likewise known as the “White Island.”

Olokun, the Yoruba Poseidon, is commemorated at the ceremonial center of Ife, Nigeria. Its foremost ritual feature is the Opa Oran Yan, a 12-foot tall stone obelisk with nails driven into its side to form a trident. The monolith also bears the Egyptian hieroglyph, sekhet, initial of the god Shu, the Egyptian Atlas. To the north, 2 miles away, lies the presently overgrown Ebo-Olokun, a sacred grove reminiscent of the same holy precinct described by Plato at the innermost sanctuary of Atlantis. The site was excavated in the early 20th century by the famous German archaeologist Leo Frobenius, who found a cast bronze head which “cannot said to be ‘negro’ in countenance, totally unlike anything Yoruban” (328). These Yoruba cultural features unmistakably point up the impact made by Atlantean culture-bearers in West Africa. Even in the remote lower Congo region, an oral tradition recalls an ancient time when “the sun met the moon and threw mud at it, which made it less bright. When this meeting happened there was a great flood.”

Oceania Deluge Tradition

Commonly related throughout the islands is the story of an octopus which had two children, Fire and Water. One day, a terrible struggle broke out between their descendants, during which the whole world was set on fire, until Water extinguished the flames with a universal flood. The myth appears to preserve the folk memory of events from 3100 through 1198 b.c., when a comet or multiple comets rained down rocky debris on the Earth. Massive, destructive waves were caused when large meteors fell into the sea.

Oduduwa II

In Yoruba folk tradition, the native queen of West Africa when her realm was invaded by Atlantean “Sea Peoples,” who refrained from deposing her because she was a competent ruler.

Oera Linda Bok

Literally, “The topic of What Happened in the Old Time,” a compilation of ancient Frisian oral histories transcribed for the first time in 1256 a.d., and published in Holland, in 1871. The Frisians are a Germanic people of mysterious origins. All that is known of their earliest history is that they ousted the resident Celts of what is now a northern province of the Netherlands, today’s Frisia, and the Frisian Islands. They also live in Nordfriesland and Ostfriesland, in Germany. Their language is closely related to English.

The Oera Linda Bok tells of the ancestral origins of the Frisian people in the island kingdom of Atland. Subjected to seismic and volcanic violence, many of its residents fled to other lands. Those who arrived in Britain, according to the Oera Linda Bok, brought with them the Tex; this was the legal structure of Atland, which, in subsequent generations, came to be known as Old English common law. One of today’s Frisian Islands is called Texel.

Other Atland immigrants sailed into the Mediterranean, where they reestablished their worship of Fasta, the Earth Mother, with her perpetual flame, at the Roman Temple of Vesta. Voyaging further eastward, a princess from Atland, Min-erva, founded Athens and, after her death, was worshiped in Italy, first by the Etruscans, later by the Romans, as Minerva, the goddess of technical skill and invention.

Two royal brothers of troubled Atland parted in mid-ocean. Neftunis steered along the shores of North Africa, settling at what later became Tunis in his honor. After his death, the Etruscans named their sea-god after him—Nefthuns, subsequently adopted by the Romans as Neptune. His brother, with a smaller contingent, sailed to the west, and was never heard of again. But his name, Inka, suggests he, like Neftunis, was a culture-founder who bequeathed his name to subsequent generations, this time in South America, where they became the Incas of Peru and Bolivia.

According to the Oera Linda Bok, the ancestors of the Frisians left Atland in 2193 b.c.. Their oceanic homeland went under the sea either at that time or sometime later; the text is not entirely clear on this matter. In any case, its late third-millennium b.c. date fits the Bronze Age context of Atlantis, and probably corresponds to the penultimate geologic upheaval and mass-evacuation described both by Edgar Cayce and Greek myth in the Ogygian Deluge, following Deucalion’s Flood. Although the Oera Linda Bok is the only Frisian document of its kind with specific references to Atlantis (Atland), folktales of sunken islands and drowned kingdoms of old are still common throughout modern Frisia.

Oergelmir

The original name of Ymir, the Norse giant whose death caused the Great Flood. The Hrim Thursar, a race which sprang into being from the only two survivors of the catastrophe, knew him as Oergelmir, a designation in keeping with variations of “Og” recurring in the flood traditions of other cultures.

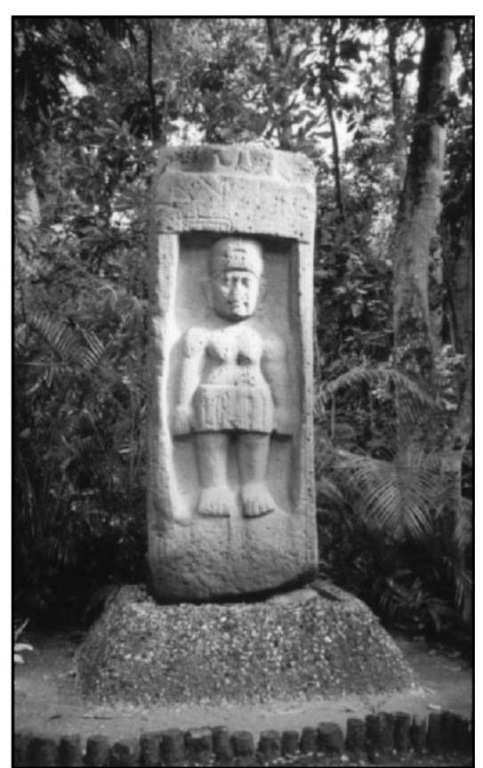

Olmec sculpture, Villahermosa, Mexico. Mesoamerican beginnings, growth, andpopulation surges from 3100 to 1200 b. c. parallel the rise and fall of Atlantis.