Dionysus of Mitylene

Also known as Dionysus of Miletus, or Skytobrachion, for his prosthetic leather arm, he wrote “A Voyage to Atlantis” around 550 b.c., predating not only Plato, but even Solon’s account of the sunken kingdom. Relying on pre-classical sources, he reported that, “From its deep-rooted base, the Phlegyan isle stern Poseidon shook and plunged beneath the waves its impious inhabitants.” The volcanic island of Atlantis is suggested in the “fiery,” or “Phlegyan,” isle destroyed by the sea-god. This is all that survives from a lengthy discussion of Atlantis in the lost Argonautica, mentioned 400 years later by the Greek geographer Diodorus Siculus as one of his major sources for information about the ancient history of North Africa.

As reported in the December 15, 1968 Paris Jour, a complete or, at any rate, more extensive copy of his manuscript was found among the personal papers of historical writer, Pierre Benoit. Tragically, it was lost between the borrowers and restorers who made use of this valuable piece of source material after Benoit’s death.

Donnelly, Ignatius

Born in Moyamensing, a suburb of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1831, Ignatius Donnelly became a young lawyer before moving with his new wife to the wilds of Minnesota, near Saint Paul. There he helped found Nininger City, named after its chief benefactor, William Nininger, but the project collapsed with the onset of national economic troubles. A born orator, Donnelly turned his writing and organizational skills to politics in a steady rise from state senator, congressman, lieutenant governor, and acting governor. A futuristic reformer, he owed no political allegiances, but regarded politics only as a means to promote his ideals, which were often far in advance of his time, including female suffrage. He was the first statesman to design and implement programs for reforestation and protection of the natural environment.

Despite his busy life as a politician, Donnelly was a voracious reader, mostly of history, particularly ancient history. Sometime before the Civil War, his sources of information opened into a veritable cornucopia of materials when he was sent to Washington, D.C., on state business. There he had access to the National Archives, which then housed the largest library in the United States, if not the world. Donnelly immersed himself in its shelves for several months, delegating political authority to others, while he virtually lived among stacks of topics. His study concentrated on a question that had fascinated him since youth: Where and how had civilization arisen? Although his understanding of the ancient world broadened and deepened at the National Archives, the answer seemed just as elusive as ever.

Not long before he was scheduled to return to Minnesota, he stumbled on Plato’s account of Atlantis in two dialogues, Timaeus and Kritias. The story struck Donnelly with all the impact of a major revelation. It seemed to him the missing piece of a colossal puzzle that instantly transformed the enigma into a vast, clear panorama of the deep past. The weight of evidence convinced him that Atlantis was not only a real place, but the original fountainhead of civilization.

For the next 20 years, Donnelly labored to learn everything he could about the drowned kingdom, even at the expense of his political career. Only in the early 1880s did he feel sufficiently confident of his research to organize it into a topic, his first. With no contacts in the publishing industry and in threadbare financial straits, he entrained alone for New York City, and headed for the largest topic producer he could find, Harper. It was his first roll of the dice, but it immediately paid off. His manuscript, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, was immediately accepted and released in 1882.

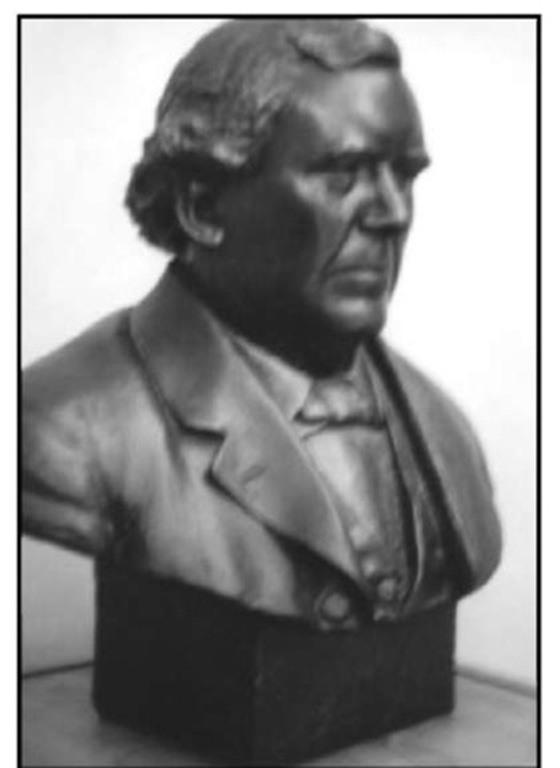

Bronze bust of Ignatius Donnelly, the founder of Atlantology, at the state capitol of Minnesota,St. Paul..

Before the turn of the 20th century, it went through more than 23 printings, selling in excess of 20,000 copies, a best seller even by today’s standards. The topic has been in publication ever since and translated into at least a dozen languages. It won international renown for Donnelly, even a personal letter from the British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, who was so enthusiastic about prospects for discovering Atlantis, he proposed a government-sponsored expedition in search of the lost civilization.

Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel, was the author’s sequel, but by the time of its release in 1883, his critics in the scientific community began marshalling bitter criticism against Donnelly, a non-degreed intruder into their academic feifdoms. They intimidated him with their high-handed skepticism, and he published no more topics about Atlantis. He wrote social novels, and returned to politics as a populist leader. Ignatius Donnelly died at the home of a friend, just as the bells of New Years Day, 1901, the first moment of a new century, were chiming in Saint Paul.

Dooy

The light-skinned, red-haired forefather of the Nages, a New Guinean tribe residing in the highlands of Flores. He was the only man to survive the Great Flood that drowned his distant kingdom. Arriving in a large boat, he had many wives among the native women. They presented him with a large number of children, who became the Nages. When he died peacefully in extreme old age, Dooy’s body was laid to rest under a stone platform at the center of a public square in the tribal capital of Boa Wai. His grave is the focal point of an annual harvest festival still celebrated by the Nages. During the ceremonies, a tribal chief wears headgear fashioned to resemble a golden, seven-masted ship, a model of the same vessel in which Dooy escaped the inundation of his Pacific island kingdom.

Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan

Famed British author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries wrote about Atlantis in The Maracot Deep for a 1928 serialization by The Saturday Evening Post, subsequently published in topic form.

Dwarka

A magnificent city built and governed by Krishna, a human manifestation of the god Vishnu. Although sometimes thought to have been located on a large island off India’s northwest coast, Dwarka’s actual position was uncertain.

Like Plato’s Atlantis, it was encircled by high, powerfully built walls similarly sheeted with gold, silver, and brass set in precious stones guarding monumental buildings and organized into spacious gardens during a golden age. This period came to an abrupt end with the dawning of the Age of Kali, the cosmic destroyer, in 3102 b.c., according to the Vishnu Purana. It tells tells how “the ocean rose and submerged the whole of Dwarka.”

The late fourth-millennium b.c. date coincides with the first Atlantean cataclysm, which inaugurated cultural beginnings in South America (the Salavarry Period), Mexico (with the simultaneous institution of the Maya calendar), the start of dynastic civilization in Egypt, the foundation of Troy, and so on. Krishna’s semi-divine origins parallel those of Atlas, the first king of Atlantis, the son of Poseidon the sea-god, by Kleito, a mortal woman.

Dzilke

Also known as Dimlahamid, the story of Dzilke is familiar to every native tribe across Canada. Among the most detailed versions are preserved by the We’suwet’en and Gitksan in northern British Columbia. They and other Indian peoples claim descent from a lost race of civilizers, who built a great city from which they ruled over much of the world in the very distant past. For many generations, the inhabitants of Dzilke prospered and spread their high spirituality to the far corners of the Earth. In time, however, they yielded to selfish corruption and engaged in unjust wars. Offended by the degeneracy of this once-valiant people, the gods punished Dzilke with killer earthquakes. The splendid “Street of the Chiefs” tumbled into ruin, as the ocean rose in a mighty swell to overwhelm the city and most of its residents. A few survivors arrived first at Vancouver Island, where they sired the various Canadian tribes. Researcher Terry Glavin, relying on native sources, estimated that Dzilke perished around 3,500 years ago, the same Bronze Age setting for the destruction of Mu around 1500 b.c. and Atlantis, 300 years later.