Sir William Crookes is best remembered for the practical application of his scientific genius, as he discovered a new element (thallium) and invented two important scientific instru-ments—the radiometer and the Crookes tube. The latter innovation acted as a key precursor to the discovery of X rays and the electron. Crookes himself participated in research on radioactivity, inventing the spinthariscope for counting alpha particles emitted by radium. However, the significance of this invention is overshadowed by his establishment of the most accurate technique for determining atomic weight, a model in scientific precision.

Crookes was born on June 17, 1832, in London, England. He was the oldest son of the tailor Joseph Crookes and his second wife, Mary Scott. Crookes received his early education at the Chippenham grammar school until 1848. Then, at the age of 15, he enrolled in London’s Royal College of Chemistry to study under August Wilhelm von Hoffman, working as his assistant from 1850 through 1854. He published his first scientific paper, on the selenocyanides of the element selenium, in 1851.

In 1854, the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford named Crookes superintendent of its Meterological Department, and the next year, Chester College of Science appointed him as a lecturer in chemistry. He returned to London in 1856 and married Ellen Humphrey; together, the couple had four children—three sons and a daughter. In 1859, he became the founding editor of the Chemical News, which distinguished itself from scientific journals by its informal tone; Crookes remained its editor until 1906.

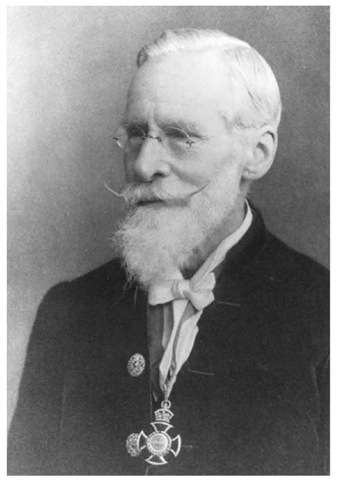

Sir William Crookes invented the Crookes tube, a key precursor to the discovery of X rays and the electron.

In 1861, while performing spectroscopic analyses (a technique recently introduced by R. W. E. bunsen and G. R. Kirchoff) of seleniferous deposits from a sulfuric acid factory, Crookes noticed an inexplicable green line in the spectrum of selenium. After isolating the metallic substance corresponding to this line, Crookes announced his discovery of the new element thallium. The Royal Society recognized the significance of this discovery by inducting him into its fellowship in 1863 (despite a controversy over propriety with C. A. Lamy, a French chemist who displayed the same metal at the 1862 International Exhibition in London).

In 1871, Crookes published Select Methods in Chemical Analysis, and two years later, he published a paper announcing his final determination of the atomic weight of thallium. This 1873 paper established a benchmark in the methodology of atomic weight calculation and was universally lauded for its accuracy and clarity. In order to make this determination, Crookes had to employ a vacuum balance, which inspired his next line of research.

Crookes published "Attraction and Repulsion resulting from Radiation" in 1874, a paper that laid the groundwork for his invention of the Crookes radiometer, announced in a paper the next year. The action of the apparatus resembled that of a paddle-wheel riverboat, except that Crookes colored his four paddles black on one side to absorb radiant energy, and silver on the other to reflect it, thus creating a directional draft of energy that set the blades in circular motion when exposed to radiant sunlight. The practical application of this instrument outweighed Crookes’s flawed explanation of its theoretical basis.

Crookes next turned his attention to study of rarefied gases in vacuum tubes. He discussed his investigations in his 1878 Bakerian Lecture and his 1879 British Association Lecture, explaining in the latter the apparatus he invented to carry out these experiments—the Crookes tube. This instrument consisted of an evacuated glass tube containing a negative electrode and a positive anode; when Crookes introduced a small electrical charge between the two, he observed an inexplicable ray emitting from the negative electrode, which he called a "molecular ray" (but subsequently became known as a "cathode ray," after Michael Faraday’s term for the negative electrode). Furthermore, Crookes observed a light-free zone at the point of discharge on the negative electrode that became known as a Crookes dark space.

Recognition for his significant contributions to the practice of scientific inquiry showered on Crookes, as he was knighted in 1897 and inducted into the Order of Merit in 1910. He served as president of the prestigious Royal Society from 1913 through 1915 and received its Royal, Davy, and Copley Medals. Crookes died on April 4, 1919, in London.