(1903-1968) Also wrote as: George Hopley, William Irish

Woolrich was one of the great innovative masters of pulp fiction, a writer whose singular talent was one of the crucial influences on the suspense story in fiction and film and on the creation of the category of dark melodrama now known as “noir.” Growing up with divorced parents, Woolrich spent much of his unconventional childhood with an engineer father in dangerous corners of Mexico. Cornell returned to New York City to attend Columbia University for a few years, then broke onto the literary scene as the author of a series of youthful Jazz Age novels inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald. This early promise of a serious writing career fizzled, as did a brief fling with Hollywood screenwriting.

With the coming of the depression, Woolrich was without prospects and lived with his mother in a Manhattan hotel room. Turning to writing again, this time merely to find some income, he peddled stories to the pulps for a penny a word or less. His first crime story was published in 1934 by Detective Fiction Weekly. “Death Sits in the Dentist’s Chair” was clever, crisp suspense about a murderous oral surgeon and the narrator’s race to save himself from the effects of a deadly cyanide tooth filling. Woolrich’s second story, “Walls That Hear You,” was even better. A man’s brother is found with his tongue and fingers cut off. The man tracks down the assailant, an insane abortionist, and the story climaxes in a grueling mix of anger, suspense, and dread.

Woolrich, in these and in many of his more than 100 other pulp stories in the next five years, gave mystery fiction an emotional intensity and delirious psychological dimension that it had seldom known. Many of his most effective early stories were imbued with the desperation and hovering violence of the Great Depression, and the settings were often the less savory neighborhoods of Manhattan, all cramped tenement buildings, dirty subway stations, dime-a-dance halls, and police interrogation rooms. The many great and memorable stories and novelettes of his pulp magazine period include “The Dancing Detective” (1938), “The Corpse Next Door” (1937), “You’ll Never See Me Again” (1939), and “Speak to Me of Death” (1937). Woolrich’s propensity for narrative hysteria was well-suited for horror fiction as well, although his ventures in this genre were relatively few. He wrote just four stories for the “weird menace” pulps that thrived in the mid to late 1930s, but two of these were classics. “Dark Melody of Madness,” published in Dime Mystery in July 1935, was a poetic and intricately structured evocation of fear and inescapable fate as a jazz musician runs afoul of the voodoo cult whose secret music he has appropriated for his own swing band recordings. There are a half-dozen climactic twists before the last haunting line: “All she says is ‘Stand close to me, boys—real close to me, I’m afraid of the dark.’” “Graves for the Living” was a tour de force of sustained suspense about premature burial and a fiendish cult, with a gut-wrenching climax as the hero searches for his buried-alive fiancee, exhuming coffin after coffin with his bare hands— the sort of race-against-time finale for which Woolrich became legendary. Woolrich could draw a reader so deeply into his protagonist’s dilemma that one finished the best of his work—and even some of the worst of it—in a state of anxious, almost unbearable empathy.

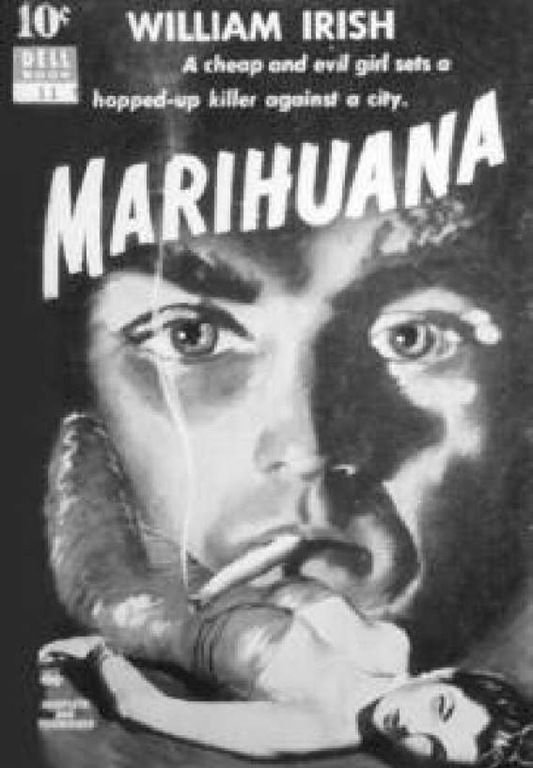

Paperback edition of the dark, suspenseful Marihuana (1951)

By the end of the 1930s, Woolrich, like many of his fellow pulp writers, began writing crime novels for hardcover publication. His first, The Bride Wore Black (1940), was a brilliant, dreamlike tale of a woman’s methodical revenge on the men who killed her lover moments before their marriage. It began his so-called black series—The Black Curtain, Black Alibi, and so on—each novel intensely suspenseful and written in the author’s irresistibly readable lyric-pulp style. Under his own name or his pen names of William Irish and George Hopley, Woolrich, with his story lines about revenge, murder, amnesia, and doomed romance and his pessimistic, paranoid vision of life on Earth, was crucial to the development of film noir and its offshoots. In the ’40s and ’50s his work was continually adapted for films and for radio, then television programs. These include such classic ’40s noirs as Deadline at Dawn (1946) and Phantom Lady (1944), French filmmaker Frangois Truffaut’s stylishly European versions of The Bride Wore Black (La Mariee etait en noir, 1967) and Mississippi Mermaid (La Sirene du Mississippi, 1969) from Waltz into Darkness, and, best of all, Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rear Window (1954), based on the short story “It Had to Be Murder,” originally published in Dime Detective magazine in 1942.

A recluse for much of his adult life, Woolrich died as he had lived, a lonely man in a Manhattan residential hotel.

Works

- Beyond the Night (1959);

- Black Alibi (1942);

- Black Angel, The (1943);

- Black Curtain, The (1941);

- Black Path of Fear, The (1944);

- Blind Date with Death (1985);

- Bride Wore Black, The (1940);

- Children of the Ritz (1927);

- Cover Charge (1926);

- Darkness at Dawn (1985);

- Dark Side of Love, The (1965);

- Death Is My Dancing Partner (1959);

- Doom Stone, The (1960);

- Hotel Room (1958);

- Into the Night (1987);

- Manhattan Love Song (1932);

- Marihuana (1951);

- Nightmare (1956);

- Rendezvous in Black (1948);

- Savage Bride (1950);

- Strangler’s Serenade (1951);

- Ten Faces of Cornell Woolrich, The (1965);

- Time of Her Life, The (1931);

- Times Square (1929);

- Vampire’s Honey moon (1985);

- Violence (1958);

- Young Man’s Heart, A (1930)

As George Hopley:

- Fright (1950);

Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945) As William Irish:

- After Dinner Story (1944);

- Blue Ribbon, The (1949);

- Bluebeard’s Seventh Wife (1952);

- Borrowed Crimes (1946);

- Dancing Detective, The (1946);

- Dead Man Blues (1948);

- Deadline at Dawn (1944);

- Eyes That Watch You (1952);

- I Married a Dead Man (1948);

- I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1943);

- If I Should Die Before I Wake (1945);

- Phantom Lady (1942);

- Six Nights of Mystery (1950);

- Somebody on the Phone (1950);

- Waltz into Darkness (1947);

- You’ll Never See Me Again (1951)