(1920- )

Although his work and his fame eventually made him a part of serious modern literature, Ray Bradbury was first a star among the readers of the rough paper pages of the pulp science fiction magazines of the more fantastic sort with lurid covers of sword-wielding spacemen, bosomy blondes, and rampaging, ray-gun-firing Martians. As a young boy Bradbury developed a taste for fantastic and horrific tales. He cultivated friendships with other young readers and aspiring writers and edited an early fan magazine. At age 21, writing with a friend named Henry Hasse, he sold his first story, “Pendulum,” to Super Science Stories. He became a regular contributor to Planet Stories, the most popular of the “soft science” SF pulps (the magazines devoted more to swashbuckling space adventure than to stories of real science-based speculation). Planet Stories published such early Bradbury classics as “Morgue Ship” and “Lazarus, Come Forth.” With each story he refined his style, known for the philosophical themes that interested him and the quietly poetic prose. In the summer 1946 issue of Planet Stories, Bradbury published “The Million Year Picnic,” the first of the stories that would eventually make up the acclaimed collection The Martian Chronicles.

Unlike so many of the technology-obsessed, dispassionate SF writers, Bradbury was something of a romantic Luddite when it came to scientific progress. He expressed a rueful view of science and progress in his stories of an ordinary family that has fled to Mars just before Earth’s inevitable self-destruction:

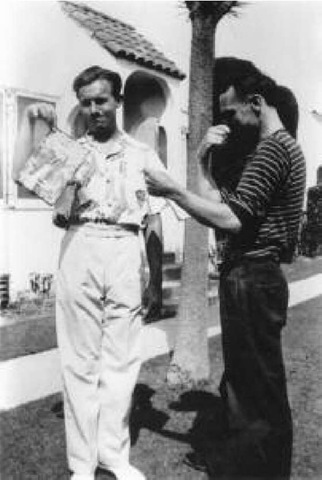

Ray Bradbury (left) with fellow science fiction writer Edmond Hamilton and a copy of Captain Future in Los Angeles, 1940 (Brackett estate)

Science ran too far ahead of us too quickly, and the people got lost in a mechanical wilderness, like children making over pretty things, gadgets, helicopters, rockets, emphasizing the wrong items, emphasizing machines instead of how to run the machines. Wars got bigger and bigger and finally killed Earth . . . that way of life proved wrong and strangled itself with its own hands . . .

When published in topic form in 1950, The Martian Chronicles made Bradbury famous. In 1953 he published another cautionary volume, this one even more pointed. Fahrenheit 451 was the tale of a thought-controlled future when alarms send fire brigades across the landscape to set fires—to burn hidden collections of the government’s most feared contraband, topics. Written in a time of industry blacklists, rampant censorship, and anti-intellectu-alism in the name of patriotism, the novel was obviously symbolic, but it also proclaimed through lucid, lyrical prose a more timeless theme, the power and allure of topics.

Bradbury’s acclaim brought him readers who had previously disdained genre fiction, and brought unusual offers like that from filmmaker John Huston to script his production of Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick. That Bradbury was the best-known “science fiction writer” in America created a certain amount of resentment among more hardcore SF readers and critics, who thought most of his work was only marginal to the genre and, in any case, not as good as others they could name. It is better to consider Bradbury as a category of one. Through the decades he has produced a unique, wide-ranging body of work, including poetry, children’s topics, screenplays, and memoirs.

Works

- Ahmed and the Oblivion Machine (1998);

- Dandelion Wine (1957);

- Dark Carnival (1947);

- Dinosaur Tales (1983);

- Driving Blind (1997);

- Fahrenheit 451 (1951);

- Golden Apples of the Sun, The (1953);

- Graveyard for Lunatics, A (1990);

- Green Shadows White Whale (1992);

- Illustrated Man, The (1951);

- I Sing the Body Electric (1969);

- I Sing the Body Electric and Other Stories (1998);

- Long After Midnight (1976);

- Machineries of Joy, The (1964);

- Martian Chronicles, The (1950);

- Medicine for Melancholy, A (1959);

- October Country, The (1955);

- Quicker Than the Eye (1996);

- R Is for Rocket (1962);

- Silver Locusts, The (1952);

- S Is for Space (1966);

- Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962);

- Switch on the Night (1955);

- Toynbee Con-vector, The (1988)