(1903-1977) Also wrote as: Kenneth Robeson

The other hard-boiled Bogart of the 1940s, William G. wrote good, entertaining crime novels about a private eye with a classic tough guy moniker, Johnny Saxon, and an unusual sideline, writing tough-guy detective stories for the pulp magazines. Bogart himself was a denizen of the pulp jungle for two decades, working both sides of the business, as writer and editor. Sometime near the tail end of the Great Depression, he took a job with Street & Smith. He remained a staff editor for many years, working in various capacities on various titles. Along the way he began contributing his own stories. By the late ’30s he had built up enough contacts and confidence to quit the editorial job and try writing for a living. He was soon appearing in the pages, and often on the covers, of numerous pulp magazines of every sort, from Range Romances to Unknown. “One of the best of the younger writers,” an editor wrote of him in an issue of The Avenger, published by his former full-time employer, Street & Smith. “He shows every sign of reaching the top in a very short time.”

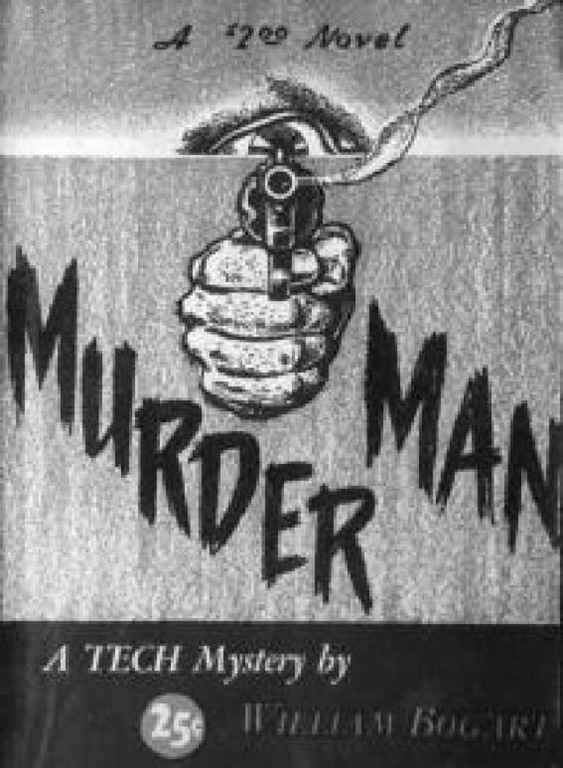

William G. Bogart’s Murder Man (first published as Hell on Fridays) is a mystery set in the pulp magazine world.

It didn’t quite go that way. But Bogart was good. Lester dent, the wizard behind Doc Savage, turned to Bogart when he needed a good backup to ghost write some of Doc’s monthly adventures. Bogart’s first was World’s Fair Goblin, printed in April 1939. The ghost writer didn’t bring Dent’s intensity to the job—it wasn’t his personal baby, after all—but he was clearly up to the job, turning out 13 Savage novels between 1939 and 1947. Dent was said to have polished or revised the ghost work, but Bogart also did some of his Docs directly for Street & Smith, published without changes.

Like many of his peers, Bogart in the early ’40s, started writing mystery novels for hardcover developers. Most were about Johnny Saxon, the Manhattan P.I. with the pulp stories to his credit. The first of these is the best and, from a historical perspective, makes fascinating reading. In Hell on Fridays (retitled Murder Man for later paperback publication), Bogart used the world of the pulp magazines as the backdrop for a crime story. The original title referred to the hectic payday at most rough-paper developers, when writers converged on the pulps to collect their checks for the week.

Hell on Fridays’ hero is a hard-boiled PI. turned hard-boiled pulp writer and now, with his muse missing in action, about to go back to detecting. On a snowswept winter morning in a crumbling Manhattan office building, Johnny Saxon wakes up in the seedy suite he shares with his business partner, “Moe Martin—Literary Agent.” The walls are covered with magazine covers, evidence of Saxon’s five years as the “prince of the pulps.” Once he had had his own detective agency and all the business he could handle, but he had walked out on it when he made his first sale. Bogart, a voice of experience, gives Saxon’s back story:

He learned formula, bought an electric typewriter, and ground out words by the ream for the fast action magazines. He wrote furiously, sometimes up to ten thousand words in a single day. In a year he was the most prolific writer in America. He started a whole new school of pulp writing . . . he’d written emotion instead of bang-bang. It was only natural. He was a romantic guy. He was—for a time—the boy wonder. It came to a point where he either had to graduate into the slicks, or burn out. He did neither. After three years he simply stopped writing. The business had lost its kick for him. . . . All he had left was the immortality of those three years.

Bogart goes on to describe Saxon’s past attempts to live off his reputation, going into the “literary consultant” racket, bleeding money from amateur writers, then trying for a comeback “via the ghost writer scheme,” putting his byline on the work of paid collaborators. “This worked fine,” he wrote, “but the ghosts were for the most part rum-sodden hacks, and once a check came in they’d disappeared. One committed suicide in a sordid Greenwich Village bar after a four-day bout—he was sixty-three years old; another landed in a straight-jacket in Bellevue.”

Was this crime fiction or confessional? Bogart’s first chapter details a hack writer’s world as bleak as Gissing’s Grub Street. But that’s only the beginning of Hell on Fridays’ tour of a largely sordid pulp world. Bogart puts his insider’s knowledge to use in the entire tale—describing barely disguised companies and real-life characters as Saxon is hired by one dime magazine developer to guard a hot new writer stolen away from a rival pulp house; the writer is kidnapped, the developer is murdered, justice is served, and private eye Johnny Saxon even gets to sell another story. For guys like Bogart this was the best possible sort of happy ending.

Works

- Hell on Fridays (1940);

- also published as Murder Man;

- Murder Is Forgetful (1944);

- also published as Johnny Saxon;

- Queen City Murder Case (1946);

- Sands Street (1942);

- Singapore (1947)

As Kenneth Robeson:

- Angry Ghost, The (1940);

- Awful Dynasty, The (1940);

- Bequest of Evil (1941);

- Death in Little Houses (1946);

- Disappearing Lady (1946);

- Fire and Ice (1946);

- Flying Goblin, The (1940);

- Hex (1939);

- Magic Forest, The (1942);

- Spotted Men, The (1940);

- Target for Death (1947);

- Tunnel Terror (1940);

- World’s Fair Goblin (1939)