INTRODUCTION

Web museums take their origin from the “imaginary museum” (Malraux, 1956). They have sparked enthusiastic claims for art democratization, or the disseminating of images on original artworks for a diversified audience without access to physical art galleries using several forms of medium (e.g., books, magazines, or catalogues). Nowadays, the advent of the Internet for heritage institutions is an indisputable turning point in the 1990s and seen as the most innovative cultural portal by both curators and educators; it holds great potential with the realism of higher-end technologies.

SEVERAL FINDINGS ABOUT THE FRENCH POPULATION

Museum Web masters have little knowledge about virtual visitors’ tastes and needs when browsing art galleries; therefore design semantic networks must be addressed. Referring to an exploratory qualitative study undertaken on 10 Web museums1 in French and English, regrouped into five main categories (i.e., archaeology/antiquity, ethnology/civilization, gistory, fine arts and heritage) according to geographical location, interface design and captions’ originality (Vol & Bernier, 1999; Bernier, 2007). We then examined some of the French population’s viewpoints with respect to three variables: profession (i.e., IT-related work), taking into account Internet familiarity (i.e., novices vs. experts) and museum practices (i.e., occasional vs. regular visitors). Thirty-seven Parisian users were gathered (21 men and 16 women) between the ages of 15 and 68 (average age of 45 years), with mainly university graduates (bachelor level).

Our methodology was inspired by the hypermedia design model, proven effective for measuring what different nationalities expect in terms of interface designs, namely (1) contents, (2) layout, (3) navigation, (4) interactivity, and (5) features (Cleary, 2000; Davoli, Mazzoni, & Corradini, 2005; Garzotto & Discenza, 1999; Harms & Schweibenz, 2001; Nielsen, 2000; Schneiderman, 1997; Vetschera, Kersten, & Koszegi, 2003). Much literature exists on the subject, but one cannot give an exhaustive account of all authors studying Internet-based systems, notably perceived usefulness of ergonomics and user’s characteristics.

Contents

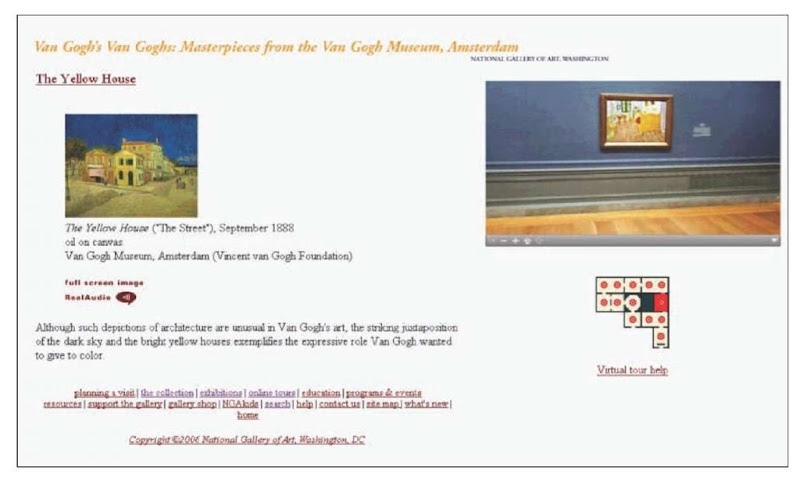

Assiduous Web surfers and regular museum visitors reported the home page to be the paramount feature, because it provides a wide selection of headings with possible explanations on the painter’s biography, its canvas, and artistic movements. The two most appreciated art galleries responding to these criteria were The Web Tours of the National Art Gallery of Washington and A Hundred Masterpieces of the Museum of Fine Arts of Bordeaux (see Figure 1).

Many assiduous surfers who are occasional visitors said that broad topics failed to arouse their curiosity, whereas regular visitors wanted Web museums with more imaginative headings for the given information. Several occasional visitors found some captions of the Metropolitan Museum of New York too general (i.e., Themes) or the wordings of the Caen Memorial (i.e., Virtual Exhibitions), others from the New Gallery of Art of Washington and the Natural History Museum of London too extensive (i.e., Education), even a few too subtle from the Museum of Lausanne (i.e., Cabinet of Curiosity) for their didactic goals. This comment is all the more true when curators offer a set of topics that are supposedly known by the general public, instead of answering what the public ought to learn. As for privileged sources of information, regular and occasional visitors are interested in: (1) art collections, (2) virtual guided tours, (3) conferences, (4) databases, and (5) upcoming exhibitions (Vol & Bernier, 1999). The latest figures (Kravchyna & Hastings, 2002) revealed that virtual visitors expect content on recent physical exhibits (80%), art collections (62%), special events (66%), and images of artworks (54%).

Layout

Some regular visitors and assiduous surfers appraised computer graphics representing explicit visual cues. This was also stressed as essential by novice surfers and occasional visitors. For instance, the iconography of Medieval Paintings in the South of France, like the Death’s-head’s caption, matched the information to be obtained and encouraged investigation. Many regular visitors were displeased looking at thumbnail images of the masterpieces, when in reality they can lose themselves in the exhibits, except for the National Gallery of Arts of Washington, where one can easily seek known or unknown paintings. Several others, mainly assiduous surfers who were regular visitors, claimed “a classy” lighting effect augmenting the paintings’ texture as provided by the National Art Gallery of Washington (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Museum of Fine Arts of Bordeaux

With respect to the visual presentation of contents, assiduous surfers who are regular visitors highly favored the plentiful homepages of the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York and of the Museum of Natural History of London, which use multiple subject areas, which had a positive result on their exploration. Regardless of Internet familiarity and museum practices, users appraised the headings Kids only of the MNH or Explore & Learn with Timeline of Art History of the MET; both museums aimed at reaching specific audiences and raised a strong interest in testing their knowledge (see Figure 3).

Navigation

Several regular visitors appreciated a topographical view of their art collections and galleries with great ease of use or a preliminary guidance derived from the real building such as offered by the Canadian Museum of Civilization. Furthermore, assiduous and novice surfers sought information in a traditional way, and therefore preferred hypertext followed by the table of contents, whereas regular visitors wanted Pop-up text boxes with features that enrich the visit. Some assiduous surfers as well as regular and occasional visitors, were displeased with nonstandardized indexes and stated a major inconvenience in becoming acquainted with most online exhibitions. Most virtual visitors that browsed the

National Art Gallery of Washington were unanimous about having the best guidance facilities. Nevertheless, many users, regardless of their Internet familiarity, complained they were forced to consult another Web page to obtain textual information on artworks.

Interactivity

Web museum designers need to highlight one media in relation with another, based on a single user-based approach, such as text leading to an image and images linking to sound. However, it is more natural to listen first and visualize second for better memorization of information (Bernier, 2003). In this respect, some novice surfers and occasional visitors indicated that images are extremely important, but that sound makes the information less grim (Vol & Leger, 1997). Several novice surfers and occasional visitors have a preference, for instance, palliative aids when visualizing masterpieces. The same users also expected a three-dimensional environment to guide them from one exhibit space to another with sophisticated software (e.g., QTVR, VRML), like the Virtual Tours of the National Gallery of Art of Washington.

Numerous occasional visitors criticized the absence or the under-utilization of audio and video comments for Medieval Paintings in the South of France, the Canadian Museum of Civilization, and the Jacques-Edouard Leger World Art Foundation, as well as for the Museum of Fine Arts of Bordeaux. Since our research was undertaken, the Leger Foundation has considerably improved its headings with Quick Survey, Art Trips, and Audio Conferences using Real Player. Moreover, according to assiduous surfers and occasional visitors, audio captions with period musical instruments or video feedback providing an historical context on the artist’s life would be welcomed, as one cannot depict a period’s feel, know an historical figure, appreciate a chemistry experiment, even visualize the Big Bang trough animated images (Bernier, 2003).

Figure 2. National Gallery of Art of Washington

Figure 3. Metroplitan Museum of Art of New York

Despite the efforts to produce attractive interactive visits, many regular visitors mentioned that the screen always remains an obstacle in terms of clear viewing, size, and texture. It was also occasionally stressed that the system’s slowness for downloading the masterpieces negatively affected its content exploration, while visitors become acquainted with a painting within a few minutes in the physical institution. Finally, some assiduous surfers and regular visitors stated that technical topics (e.g., space, environment, or natural sciences), as well as audiovisual formats, are most suitable for introducing exhibitions online, especially for social, historical, or political matters (Giaccardi, 2004; Tinelli, 2001), or within immersive exploration with onsite and remote visitors, or bypassing a covisit of the traditional museum (Galani & Chalmers, 2004).

Features

Several assiduous surfers and regular visitors stated that networked communication channels (e.g., Listservs, newsgroups, IRC) were seldom developed and thus can act as original hubs or initiate dialogues with curators with similar interests. The rise of online forums in the 1990s, like H-MUSEUM and MUSEUM-L for interdisciplinary cultural-related questions, is an indication for strengthening the museum community and intended for targeting common art knowledge, but they have not yet managed to reach the general public (Bernier & Bowen, 2004). Some assiduous surfers occasional or regular visitors, a humanistic perspective such as the people’s lifestyles rather than intellectual explanations, like the Canadian Museum of Civilization, or highlighted observations on the paintings’ characteristics on artworks as offered by Symbols in Art and Composition of the Metropolitan. Other users, mainly novice surfers and regular visitors, requested a virtual museum to be an open window onto the world, as it is the case for the Caen Memorial. This museum gives numerous links to other war-related subjects, such as the Australian War Memorial, the Hiroshima Bomb Museum and the BBC history.

SUMMARIZED OUTCOME

The results have shown that the French users, regardless of their museums’ practices and Internet familiarity, favored national art galleries using selected headings (i.e., a breakdown of information) sorted by meaningful captions and clear terminology, with navigational consistency through ergonomics recalling the premises of the real building. Furthermore, their prevailing perceptions about the Web museum is a facility that presents contents on fine arts and accentuates the aesthetic feeling of masterpieces through high-quality resolution images. We also learned that the chosen paintings are of utmost importance, because the French expected a great number of artworks and comprehensive explanations of them, all offered with user-friendly interfaces and innovative software for visualizing masterpieces in vivo. These findings confirm those noted by many academics (Bowen, Bennett, & Johnson, 1998; Davallon, 1998; Futers, 1997; Haley-Goldman & Wadman, 2002; Kravchyna & Hastings, 2002).

The museum has evolved from an information pool to a content provider and is no longer solely about preserving and making their artworks accessible to audiences, but also gathering captivating facts on important figure s or significant events (Falk & Dierking, 2000). Hence, the instructive role of Web museums is of benefiting from additional forms of content, that is as much as for pre-visit and post-visit information in order to accommodate several pedagogical approaches and complement physical visits (Bernier, 2005; Galanni & Chalmers, 2004; Mintz, 1998; Mokre, 1998; Tinelli, 2001). Furthermore, the curators must take into consideration the existing museum practices, having particular concerns for first-time visitors with little Internet expertise.

CONCLUSION

Museologically speaking, the Web museum should fall into four learning styles (Bernier, 2007; Gunther, 1990) for valorizing cultural resources: (1) giving facts and detailed information (e.g., databases), (2) supporting pragmatism and skill-oriented explorations (e.g., virtual guided tours), (3) sharing ideas (e.g., online forums), and 4) bringing about self-discoveries (e.g., quizzes).

KEY TERMS

Computer Graphics: An expression that encompasses design, labels, and forms with various texture, fonts or frames for highlighting a Web page. As for Web museums, a small graphic or thumbnail can be tiled to create an interesting background using a range of resolution, pixels, and color gradients—either radiance, transparency, or sharpness—in a manner that affects the aesthetic beauty of masterpieces.

Cultural Portal: A network service for multiple heritage organizations (e.g., museums, science centers, historical sites, castles) that allows discovery of the arts, monuments, or places and act as a representative of the material and immaterial cultural inheritance through nature, science, people, values, and objects. For national art galleries, these cultural inheritances are visible within masterpieces (e.g., paintings, prints, sculptures), by emphasizing different artistic movements (e.g., realism, cubism, impressionism) with regard to nationalities, religion, and gender.

Digitized Artwork: A high-resolution reproduction1 of an artwork incorporating texture, light, and colors for presenting the visual details and rendering the pigments, hues, and tones of painted oils, watercolors or impastos, and so forth, and thus amplifying the artists’ brushstrokes. This is in order to depict the realism of the actual masterpieces at a level deemed worthy of the museum’s reputation1. A reproduction is a visual image available in digital form for a licensee who has the required permission beyond the initial use; curators must then comply with copyrights for reusing masterpieces in the public domain (Kitchin, 1996).

Heritage Organization: Abuilding, place, or institution devoted to the acquisition, conservation, study, exhibition, and educational interpretation of objects having scientific, historical, or artistic value (American Heritage Dictionary, 2003). Their numbers include both governmental and private museums of anthropology, art history and natural history, aquariums, arboreta, art centers, botanical gardens, children’s museums, historic sites, nature centers, planetariums, science and technology centers, and zoos (American Association of Museums, 2000).

Interface Design: Avisual organizational space for classifying or grouping contents strategically, that is, through a schematic arrangement of information with interesting menus and creative hyperlinks, intriguing captions, specific headings, clear terminology, recognizable computer graphics, and higher-end technologies; in short, a user-friendly ergonomic easily accessible for virtual visitors.

Online Exhibition: A Web-based facility displaying images and using content interpretations for understanding fine arts, taking into account both users and art-focused paradigms to produce new meanings of the artist’s inspiration and recreate the objects’ historical context; hence encouraging the people’s curiosity to educate interactively, while presenting a unique and extensive view of art collections.

Virtual Visit: A resource that provides a visit within a real location, like an historic place and physical exhibitions. Virtual visits often aim at replicating real sites or art galleries, but they can also be fictitious spaces or imaginary exhibitions, benefiting from inventive learning attainments using interactive software, like Shockwave, Macromedia, Real Audio, or QuickTime Virtual Reality (M. Alexander, personal communication, July 2004). Hence, the utilization of higher end technologies conveys an exceptional aesthetic viewpoint focusing on interactivity and human experience.

Virtual Visitor: A term to designate a single user browsing museum Web sites, whether local or from a foreign country, that offers revealing data about the tendency of visiting online exhibitions, in particular access issues, date and duration of the visit, number of pages consulted and headings selected (Peacock, 2002).

Web Museum: A virtual gateway to online exhibitions displaying objects and digitized artworks, as well as museum-related information incorporating virtual visits (Dietz, Besser, Borda, Geber, & Levy, 2004).