INTRODUCTION

The Internet has revolutionised the way that business is conducted by customers and organisations that serve them. Texts are now being devoted to explaining how e-business can be practically undertaken, for example see Lawrence et al. (2003). There is a rapidly emerging trend of organisations using Intranet portals for internal business processes and communication between employees and their organisation.

Systems that deploy Intranet portals with intelligent agents and e-processes have replaced routine procedural knowledge used by clerical and lower level management levels. These portals facilitate self-service as a first step toward developing more knowledge-intensive knowledge management (KM) portal applications. However, the greatest value to be derived from well-designed intranet portals is probably their potential as a KM tool (Lloyd-Walker & Soutar, 2005). Portals must be convenient to use and represent an advantage to users over more traditional means (Peansupap & Walker, 2005a). Also, appropriate change management practices should be adopted when planning, deploying, and applying portals as a tool for KM in an organisation to ensure that an appropriate knowledge sharing culture exists where both the organisation and its staff values and rewards knowledge-sharing (Fernie, Green, Weller, & Newcombe, 2003; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; Lloyd-Walker et al., 2005).

We will now focus on our main theme of describing a prototype KM portal developed for a major Australian construction contractor. We set aside further detailed discussion of the important diffusion and adoption issues. These are addressed in depth elsewhere (Attewell, 1992; Peansupap & Walker, 2005b; Rogers, 1995).

This article is structured as follows. We have provided a brief introduction to knowledge portals in this section and highlighted further references for ICT diffusion. In the next section, we provide background to the prototype KM portal tool to enable readers to understand its scope and limitations. In that section we also briefly explain how a soft systems methodology (SSM) approach facilitated the development of our ideas. We then focus our next section on describing the prototype. This is followed by a brief discussion of future trends and concluding comments. The value of this work lies in its novel approach to designing a knowledge portal and the conceptual work that supports this prototype KM system.

BACKGROUND: THE SSM PROCESS

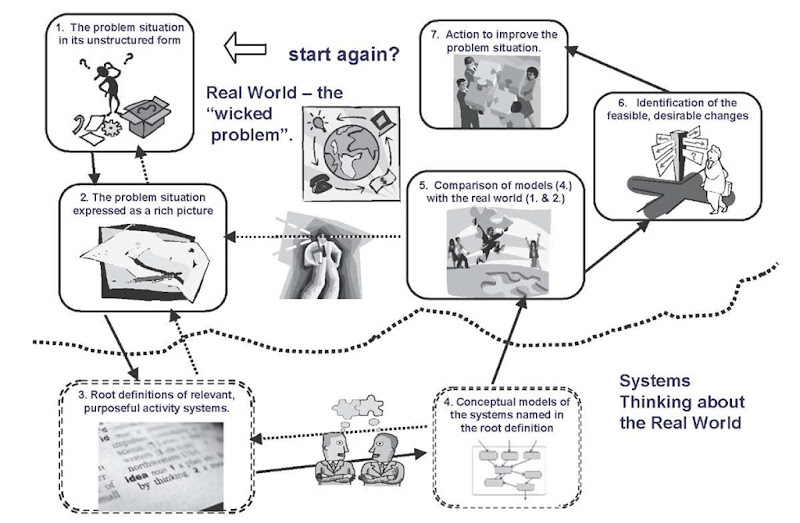

The KM tool described in this article evolved from a PhD research project of KM as applied by a major Australian construction contractor (Maqsood, 2006). More specifically, it focussed on investigating how knowledge in the pre-tender process of prospective construction projects is identified, shared, and used. This knowledge is related to establishing and maintaining contact with clients and design teams associated with these projects and potential members of the supply chain that would be involved in tendering for the project. The research applied a SSM approach for gathering data, this yielded unexpected insights, and sources of rich tacit knowledge that had been hitherto poorly explicated, shared, and understood by many participants in the process. The development of rich pictures (a technique of representing a complex situation as a kind of cartoon that highlighted salient issues through dialogue balloons and symbols) was used as part of this SSM approach. SSM, in its idealised form, is described as a seven-step process as illustrated in Figure 1 (Checkland, 1999, p. 162-183). This yielded a potentially powerful means whereby participants could visualise knowledge assets and make sense of complex situations. We decided that rich pictures could provide a stimulating visual representation of a knowledge intranet portal, which could serve as a tool for managing knowledge about a process including mapping knowledge assets that could be rapidly accessed via that portal.

The portal is currently a prototype tool developed from the PhD work that was tested by potential users for their reaction (which was generally favourable). While it is yet to be developed to a production stage, it nevertheless provides an intriguing approach to developing knowledge portals, not only for the pre-tendering management process but also for a range of other processes. This could also deliver a widely linked process map for an organisation that could enable KM to be developed through a business process redesign and renewal.

A soft system thinking approach seeks to explore “messy” problematic situations that arise in human activity. However, rather than reducing the complexity of the “mess” so that it can be modelled mathematically (hard systems), soft systems strive to learn from the different perceptions that exist in the minds of the different people involved in the situation (Andrews, 2000). SSM may be used to analyse any problem or situation, but it is most appropriate where the problem “cannot be formulated as a search for an efficient means of achieving a defined end; a problem in which ends, goals, purposes are themselves problematic” (Checkland, 1999, p. 316). More detail on this approach is explained in Walker, Maqsood, and Finegan (2005) and is briefly summarised as follows.

SSM Stages 1 and 2

The problematic situation was first identified in its unstructured form. The situation revolved around problems involving the pre-tendering decision and the way that it was often handled. Knowledge was poorly transferred and all the participants we interviewed felt that the pre-tendering decision could have been accomplished much more effectively. In Stage 2, knowledge was unearthed to explicitly express the problem. This involved interviewing as many participants in the situation as was practicable who could explicate their tacit knowledge about that situation. Tacit knowledge, feelings, and perceptions were made explicit through developing rich pictures that represent a connective human communication channel expressing the situation through an elicitation process from interviews and possible surveys. Respondents were also encouraged to graphically express their unease.

SSM Stage 3 and 4

This comprised the interpretation of the rich picture (refer to Figure 7) into a root definition to take the rich picture and offer a more systemic and formulaic summary that explicitly described the situation. The root definition is the chosen system expressed in statements, which incorporate the points of view that make the activities and performance of the systems meaningful, providing the analyst with a framework for ensuring that all points of view and interest are considered in the knowledge elicitation process. Stage 4 involved developing an account of what must be done to achieve the transformation described in the root definition. This is generally illustrated as an activity model and uses whatever techniques may be available.

Figure 1. SSM approach as a seven-stage process

SSM Stage 5, 6, and 7

In Stage 5, we explored together with the study participants, questions needing to be addressed, assumptions to be re-visited and dysfunctional behaviours/actions to be remedied by comparing the ideal model represented in Stage 4 with what is perceived to be the way things actually happen. This stage provides a reality check for Stage 4 and challenges owners of the situation to rethink and re-analyse underlying assumptions to reach a more creative and fulfilling outcome. Stage 6 involved formulating specific recommendations and implementation plans. This often triggers organisational structure changes, procedures changes, and/or organisational culture change. Action is generally taken in Stage 7 to implement changes and/or restart the process using feedback loops to test and monitor changes made.

USING THE SSM PROCESS AS A KM TOOL

SSM is both a reflective learning process and an action learning approach to problem resolution (Argyris & Schon, 1996; Schon, 1983). It addresses the principal failing of previous attempts to capture knowledge in expert systems (an early manifestation of the study of KM). It does this through the appreciation of context, the validity of a wide range of perspectives of the described situation, and the whole concept of reality as independent truth. SSM addresses these problems through its inherent acceptance of the multiple realities experienced by different people with different worldviews and life experiences that have formed the lens through which they perceive any situation.

The KM portal described in this article is based upon the knowledge advantage (K-Adv) concept that recognises the need to manage the duality of both tacit and explicit knowledge. Its strength lies in its recognition of the primacy of focussed intelligent leadership that envisions how knowledge assets can be identified, nurtured, and harnessed as well as its advocacy of providing the essential human infrastructure that is supported by an enabling ICT infrastructure. An organisation requires a coordinated approach to gain and maintain a knowledge advantage that:

1. Nourishes the leadership capabilities to establish and deploy a vision to develop a capacity for sustained knowledge advantage;

2. Supports the people management necessary to effectively use their knowledge in business activities; it comprises systems that are supported by organisational processes, which facilitate the mobilisation of knowledge resources; and

3. Provides the necessary enabling information and communication technologies (ICT) infrastructure that encompasses hardware, software, and network delivery facilities, together with a support system.

For more details about the K-Adv, readers can refer to Walker, Wilson, and Srikanathan (2004) or Walker et al. (2005). .

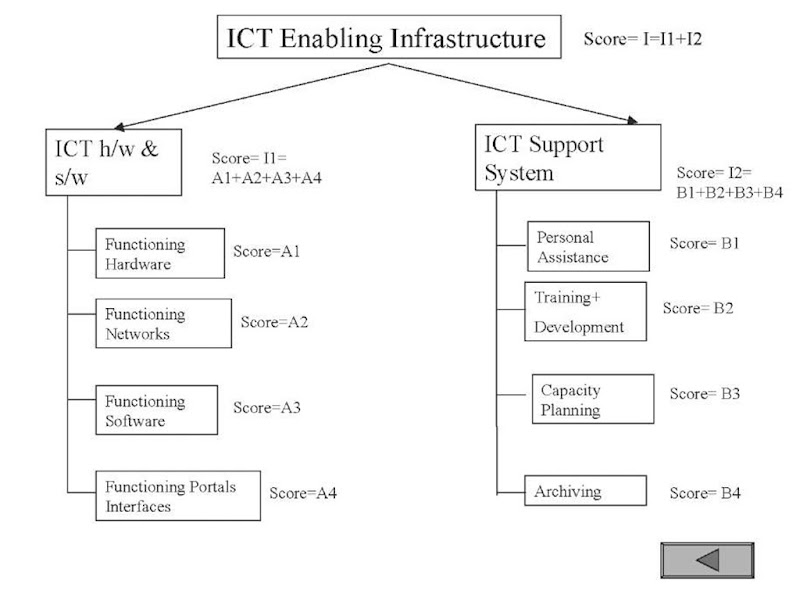

The Knowledge Audit Module

The purpose of the knowledge audit module is to efficiently facilitate KM gap analysis so that audited organisations can assess their maturity level for each KM infrastructure component. The scope of this article limits us to discussion of only one of the three K-Adv infrastructures. As Figure 3 indicates, each of the two main elements of the ICT enabling infrastructure has four sub-elements that can be scored. Scoring may be undertaken in a variety ways, by using a combination of auditing information such as documentary evidence from an asset register, by observation (seeing what is actually available), or by gaining opinions from frequent users.

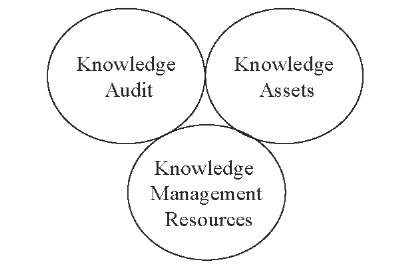

Figure 2. Three modules of the e-tool for knowledge management

Figure 3. Auditing ICT enabling infrastructure

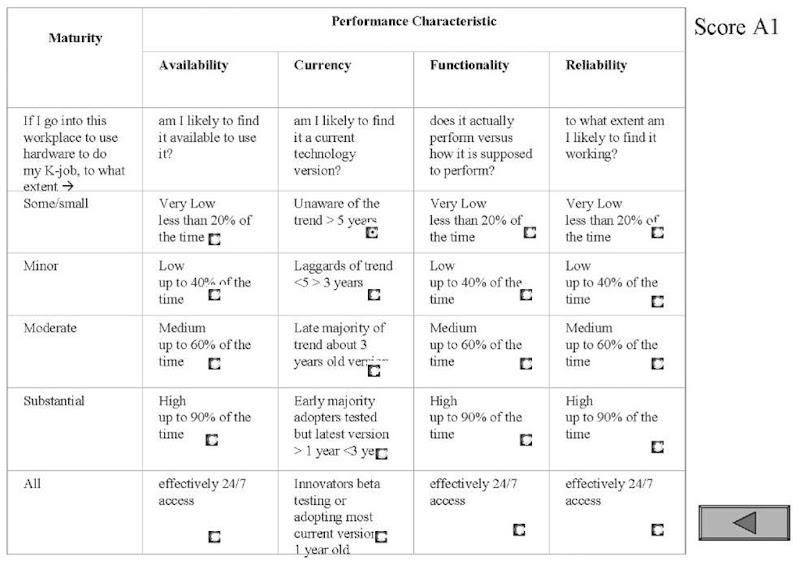

The assessment process begins with pertinent questions being asked about the state of the infrastructure elements. Figure 4 shows the portal screen image that poses the broad question “If I go to this workplace to use hardware to do my knowledge job, to what extent…” applied to the functioning hardware component in terms of its availability, currency, functionality, and reliability. Five maturity levels scored from 1-5 give a tangible measure of its level of support. This can be used to benchmark one workplace against others or to provide a gap analysis tool for scoring the “desirable state at time ‘T’ in the future” against the “now” situation. Cell descriptors were tried and tested with users for simplicity of use and being easy to understand. This was a beta-test so we remain open to suggestions for improvement in what is being measured and how it is being measured. This prototype KM portal provides a useful tool that can be adapted and used by anyone interested in doing so.

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show how the tool can be used to audit at a variety of levels—the micro level of a cell (e.g., reliability), a macro level of an infrastructure component (functioning hardware) or even at the infrastructure level (ICT enabling infrastructure). Each level of analysis can provide insights of what KM tools are available and used for knowledge work to facilitate a knowledge advantage.

The Knowledge Assets Module

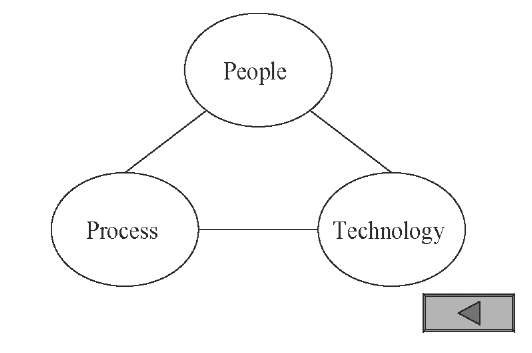

The second module of the e-tool is related with the identification ofknowledge assets. Knowledge assets in an organisation can be conceptualised as a triangle of people, processes, and technology that interact to accomplish a certain task.

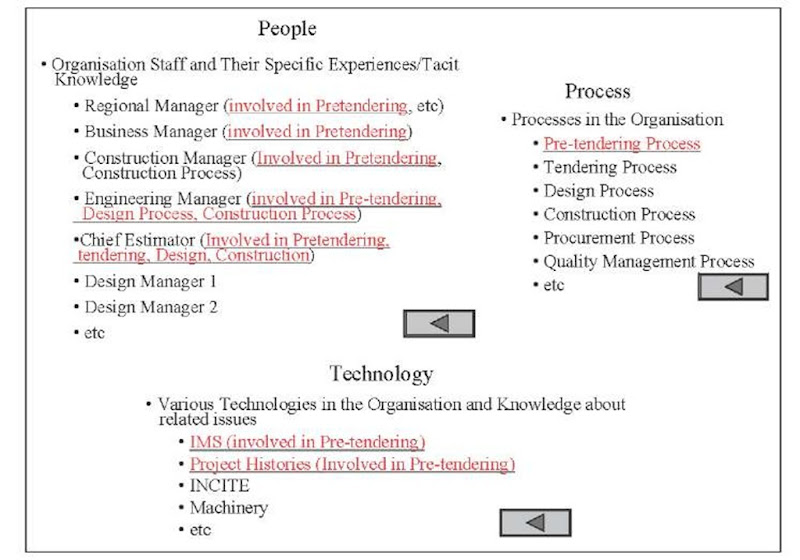

Each of the elements shown in Figure 5 are clickable from the top-level portal entry point illustrated in Figure 2 to be expanded as shown in Figure 6 for the people process. Each link inside the brackets connects users to further resources in the organisation’s ERP system or other IT data and knowledge base infrastructure. The Figure 5 knowledge asset module links to processes and technology screens similar to Figure 6 that also link to the organisation’s data and knowledge bases.

SSM investigation can be undertaken for each of the processes listed in the process part of Figure 6. This helps to unearth knowledge assets involved with people and technology processes. We selected the pre-tendering process in our research project to illustrate how the KM portal can function. The SSM research exercise helped us to identify and electronically link various knowledge assets through our development of rich pictures. These links allow users access to identified knowledge resources within the system described by the rich pictures for an understanding that particular process.

The Knowledge Management Resources Module

This module was accessed via Figure 6 and also provided a further format for the portal screen entry point to any knowledge asset as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 4. Framework for auditing “functioning hardware” through scoring

Figure 5. Knowledge assets

People intimately involved in the process illustrated in the Figure 7 rich picture are linked through processes (as illustrated in Figure 6). The rich picture helps them to understand the process concerned and they can click on the shaded dots to drill further down to access knowledge and contacts etc. These in turn are linked to the organisation’s data and knowledge bases. The screen image shaded dots illustrated in Figure 7 provide links to many resources. Alternatively, straightforward links in people and technology shown in Figure 6 also gave users access to knowledge resources available on an organisation’s IT data and knowledge bases. In this way, the portal prototype provides a fully structured KM tool that not only provides people in the organisation rapid access (only a few clicks away) to knowledge assets, but also provides the organisation with a useful auditing and benchmarking tool.

The exercise in developing the entire prototype knowledge portal previously illustrated was valuable in highlighted how links between existing knowledge assets are currently poorly available to users when they need them at short notice. For example, research participants we interviewed had current phone numbers for many colleagues that they would need to contact, but details would be predominantly stored privately in hardcopy form, stored on hand-held devises, or stored in memory on mobile phones. Company phone lists are often out of date with duplicate lists providing conflicting information. Likewise, URL links can be obsolete. The effort to maintain and integrate IT databases emerged as a key issue from our research exercise. Also, a vital issue underscored by developing the prototype portal is that the much-needed knowledge bases (rather than information) are either unavailable or poorly structured.

FUTURE TRENDS

The more obvious trend highlighted by our prototype development is the growing appreciation of the critical value and competitive advantage of KM systems that can rapidly link people, processes, and technology. This was seen to enable people to be more productive within time constraints imposed by tight tender deadlines and trigger points leading to a tender submission. This is encouraging, but we only investigated one company—a construction industry leader being one of the largest 5 or 6 construction contractors in Australia. This suggests a healthy awareness of the value of KM but an underdeveloped realisation of KM as a core competitive competency.

Figure 6. People process and technology knowledge assets

Figure 7. SSM rich picture portal access screen

The technology to link information bases and even to develop and maintain sophisticated context-rich knowledge bases is already available. The gap lies with organisational leadership to commit to substantially invest in not only well-integrated IT systems, but to also to invest in supporting their people to use this technology. This leadership gap is a serious barrier to realising current potential without even considering how emerging technologies could exacerbate the current leadership gap. Voiceover Internet technology already allows, for example, people to use SKYPE to maintain contact with colleagues stretched out over the globe using their computers as a telephonic device. This current potential allows knowledge resources in Figure 6 to link people to directly talk to each other via their computers.

We believe that future trends will centre on people and leadership improvements. Leaders will focus on two things. First, leaders need to consolidate and improve existing competencies in using knowledge assets. Second, they need to improve collegiate behaviours to leverage organisational and people-related competences. These behaviours should be soundly recognised and rewarded by organisations to strengthen people’s creative and innovative powers.

CONCLUSION

This article emphasises the people and leadership gaps that need to be filled rather than heralding any further need for ICT advances. The research exercise in developing a knowledge portal tool quickly exposed the limits of current organisational integration of information and knowledge bases. We presented a series of screen images that were developed using a tool that comprised a series of linked PowerPoint slides to demonstrate a model that could be further developed.

The SSM part of our study revealed that much of the problem lies with people-related issues. These are in turn driven by indifference by an organisation’s leadership toward committing the necessary energy and funds to integrate existing information systems and develop KM applications that extend beyond merely providing IT for information access (rather than delivering deep contextual knowledge needed for effective KM).

We also discovered that the organisation studied had not adequately addressed many technical support issues such as providing sufficient ICT support to enable people to seamlessly click on a link and be able, for example, to automatically phone, fax, or e-mail a colleague. Other people related issues yet to be resolved include providing incentives for mentoring, knowledge creation, and sharing. We saw much evidence of informal help and support between people but the organisation had yet to establish formal arrangements that might ensure wide inclusion of those, for whatever reason, may be currently marginalised.

KEY TERMS

Community of Practice (CoP): Etienne Wenger defines a community of practice (CoP) as “groups of people informally bound together by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise” (Wenger & Snyder, 2000, p. 139). However, Wenger and others have described how organisations can encourage and support a COP. A COP shares knowledge and skills and sustains its members through obligation to exchange knowledge, providing access, and accessibility to shared insights and knowledge about the practice of work (Wenger et al., 2002, p. 4).

Information Communications Technology (ICT): This technology includes groupware applications such as intranets, e-mail, and an array of devises to transmit information in electronic form.

Knowledge Management (KM): The creation, sharing, and use of knowledge in a systematic way that adds meaning and context to information.

Rich Pictures: Ways of representing complex situations through cartoon-like representations. Constructing rich pictures requires intense investigation of the situation being described and capturing the essence of it and communication of key concerns and solutions through these illustrations. They convey a deeper sense of the situation than mere text because relationships between elements of the system of the situation being described as well as the emotional undercurrents documented in the cartoon-like pictures.

Skype: A free software package that links people together to enable voice messaging and video conferencing (http://www.skype.com/helloagain.html)

Soft System Methodology (SSM): Uses soft systems thinking to explore messy problematic situations that arise in human activity. It strives to learn from the different perceptions that exist in the minds of the different people involved in the situation. It uses a seven-step approach to map the elements of a situation in order to be able to better describe the situation and present a model of it in terms of its root cause, SSM, in its idealized form, is described as a logical sequence of seven steps (Checkland, 1999, p. 162-183) as described in the text.