INTRODUCTION

Web portals continue to grow as a force that could shift the balance of power between buyers and sellers and, therefore, could alter the structure of channel systems in many industries. In late 2005, the increase in the importance of portals appears to be reflected in their market capitalization, exceeding that of more traditional media and communications companies (see Figure 1).

Today, the Internet provides access to a vast data repository. Information on product pricing and quality that used to take hours to unearth can now be accessed in seconds with a click of a mouse. However, despite the ease of data access, one issue remains: how to find that piece of relevant information within all the data. Digital technology has reduced the cost of content creation, which has increased the amount of content or data available (e.g., replacing the typewriter with word processors and desktop publishing). Together with cheap digital distribution via the Internet and Web, much of this data is now available online. What remains is the challenge of finding relevant and reliable information. This issue is being addressed by one of the dominant forces in the online arena, the Web portal.

EVOLUTION OF PORTALS

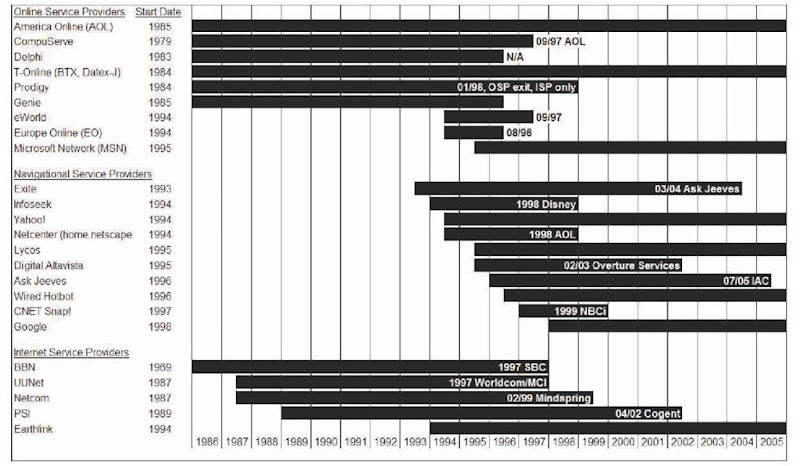

Traditionally, a portal has been viewed in a physical sense, as a door or entrance (Merriam-Webster, 2005). With the proliferation of the Internet and electronic media, the term “Web portal” came into existence as a Web site that “provides a starting point or gateway to other resources on the Internet or an intranet” (Wikipedia, 2005). The roots of Web portals—or navigational service providers, a term initially used in the 1990s—can be traced back to the proprietary online services business of the 1980s, which was dominated by three companies: America Online (AOL), CompuServe, and Prodigy (a joint venture between IBM and Sears; see Figure 2). Each online service provider built its own proprietary client/server system to provide the service. A user had to install a modem and a provider’s client software to be able to dial into the local phone network and then to log onto the provider’s remote server system. The service lineup included a choice of communication (e-mail, chat), information (news), entertainment, and transaction services (home shopping). The success of these services, and AOL in particular, coincided with the emergence of Internet and Web standards in the early 1990s (TCP/IP and http, html, and URL, respectively). These standards are open protocols, and their use eventually triggered a chain reaction leading to a disruption in the marketplace. This phenomenon could be observed in the mid 1990s, when new companies such as Yahoo! entered the market and many old online service providers disappeared (see Figure 2). The ultimate trigger of change was different economics: First, standards are cheaper than proprietary solutions. Second, they also introduce an interface between two systems, essentially splitting on old system into two components. As IT is used to automate business processes, an IT standard can also allow for the separation of a business process into two segments. In other words, the introduction of a standard presents a company with a choice: operating both segments or focusing or specializing in only one part of the old business. Economic theory suggests that specialized operations enjoy production cost advantages and companies tend to specialize (Malone, Yates, & Benjamin, 1987). An example of how open standards have led to specialization and the creation of a rich business ecosystem of competing and complementary vendors can be seen in the evolution of computing from vertically integrated mainframes to component-based personal computers (PCs). The introduction of a common set of interface specifications allowed a break up of the computer into hardware and software components, with software being further divided into operating system and applications (Rappaport & Halevi, 1992). With the success of open standards on the Internet, the functions of the old online service providers were broken out into specialized components, which created rich opportunities for new entrants (navigation/search, programming and content channels, and Internet access; see Figure 2).

WhileAOL dominated the industry throughout the 1990s, it has since lost power to “new entrants” like Google, MSN, and Yahoo! (The Economist, 2005a). MSN is the most similar to AOL, and offers content and search functionality on its Web site. Yahoo! focuses on categorizing Internet data into directories and enhances the user experience through page customization with its “My Yahoo!” service. As a result, Yahoo! leads the market with number of unique site visitors (eMarketer, 2005). On the other end of the spectrum, Google has been focused on returning the most accurate results for a given search query, and as a result leads in the share of searches performed online. Lately, additional features developed by the company have increased the site’s functionality beyond the core focus on search. Google’s recent expansion of their partnership with AOL (Wall Street Journal, 2005) continues the consolidation process. In addition, as the portals’ search technology continues to develop in both power and sophistication, their reach has begun to penetrate ad markets that were previously the territory of large print publications serving specific geographical locations and communities of interest (The Economist, 2005b). Advertisers are attracted to portals and search engines because of their ability to deliver more targeted ads. Portals have also begun to emphasize enriching user profiles (My Yahoo!), which could allow for even more narrowly targeted ads. Furthermore, there is greater accountability online than off-line: click-throughs and, therefore, ad performance, can be tracked and billing can be performance-based, which increases a seller’s return on marketing investments. As advertising dollars continue to migrate from the print to media, a key question emerges: What approach to Web portals will create the richest and most relevant customer profiles for advertisers, a “package of services” similar to what Yahoo! offered in 2005, or a “functional specialist” similar to Google’s 2005 offering?

Figure 1. Market capitalization of telecom and media companies

Figure 2 . Evolution of portals

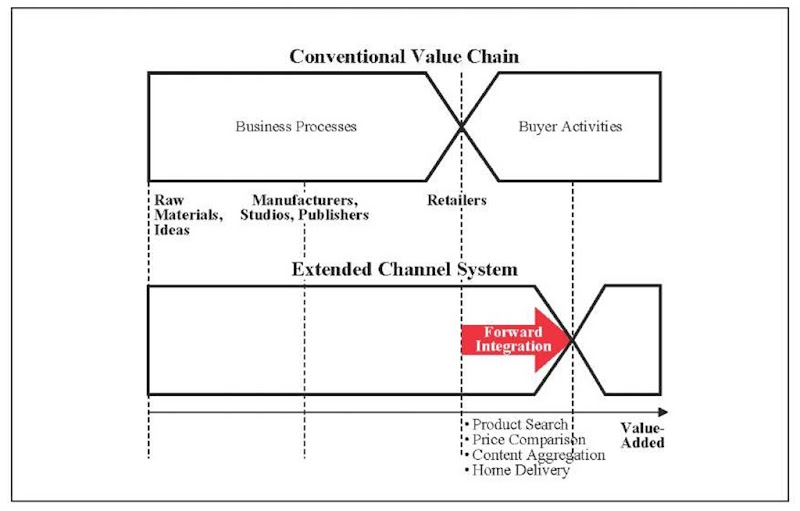

Figure 3. Extended electronic channel system

NEW BUSINESS SPACE: EXTENDING THE TRADITIONAL VALUE SYSTEM

From an industrial organization theory point of view, the Internet-enabled change in the interaction between a consumer (demand side) and vendor (supply side) led to an extension of the traditional value system (see Figure 3).

Vendors are doing more today. Activities that the consumer had to perform manually (such as contacting multiple stores to search for a product and find a low price) are now being supported online by information systems. Today, users push buttons online, while the systems have been designed, built, and implemented by sellers, which continue to spend money on operations, maintenance, and updates (Schlueter Langdon & Shaw, 2000). This software-enabled automation of business activities, also referred to as “softwarization” (Schlueter Langdon, 2003a), has opened up new ways to connect with customers. Softwarization of customer interaction remains an ongoing process. The extension of the industry values system represents an untapped market and business opportunity. For investors the two key questions are: Where is the most lucrative opportunity? Who is best positioned to take advantage of it? These questions have been answered for some of the first electronic channels (see Figure 4); however, the arrival of new technology such as mobile data fuels softwarization and forward integration, and constantly creates new business opportunities for incumbents (e.g., telecoms and DSL) as well as new entrants (such as Google and search) (Fife & Schlueter Langdon, 2004).

How To Conquer The “NEW BUSINESS SPACE”

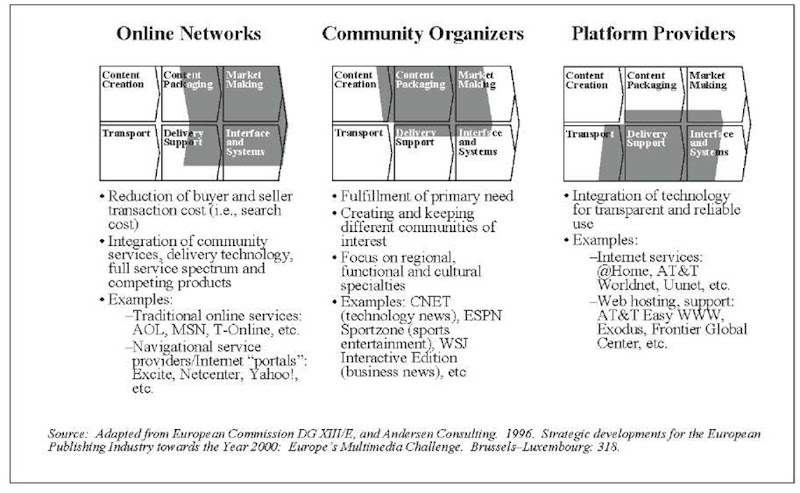

Of the many companies that entered the new business space, few have survived and succeeded in creating a sustainable business. The failure of the many and success of the few became the focus of many studies. One of the early empirical investigations suggested that opportunities fell into three distinct categories or strategic roles (see Figure 4; Schlueter Langdon, 1996; Schlueter Langdon & Shaw, 1997, 2002). The study was case-based and relied on the structure-conduct-performance paradigm of industrial organization theory (Bain 1956, 1968; Mason, 1939, 1949; Stigler, 1968), a theoretic foundation widely used in the analysis of industry structure change (for a historic perspective, see Chandler, 1990).

In a nutshell, the study described the structure of the emerging electronic or “virtual market space” (Rayport & Sviokla, 1995) using an industry classification or electronic value system concept, called 2-3-6. This 2-3-6 concept allowed for a consistent observation of horizontal and vertical integration activities of companies (e.g., telecom companies buying content providers). Trends in these observations provided clues for the identification of economic incentives that could explain the observed behaviour of the firms (transaction cost savings, scale advantages, etc). As a result, different clusters or strategic roles with different economic conditions or characteristics emerged (online networks or portals, community organizers, and platform providers; see Figure 4). This systematic uncovering of underlying economic forces provided a robust foundation for strategic decision-making in emerging digital interactive channel systems. It has since been updated and expanded to explain events in the emerging mobile media ecosystem (Fife & Schlueter Langdon, 2004).

Figure 4. Strategic roles in emerging e-channels

The 2-3-6 classification concept differed from other electronic value system concepts. It recognized activities related to “content” and electronic delivery systems as parallel strings of core processes (see Figure 4). This parallelism of infrastructure and content is also of great strategic importance in the U.S. cable television industry, where providers, such as Time Warner Cable, have leveraged ownership of cable infrastructure to gain control over access to content and programming by tens of millions of subscribers. In the area of online services, the issue of infrastructure access extends beyond network infrastructure to include human computer interfaces (such as the screen of the Windows operating system), as well as software applications (such as the Web browser).

BENEFITING FROM SUPERIOR ECONOMICS

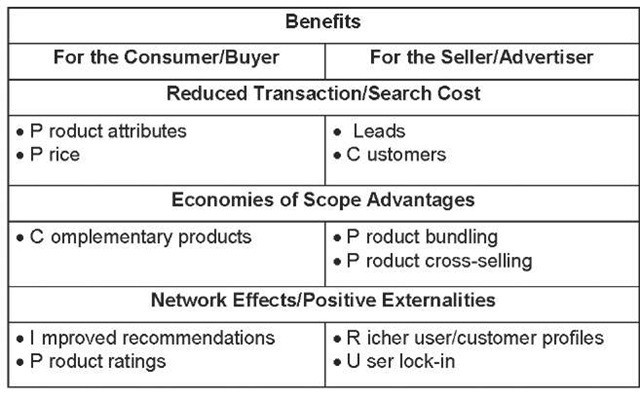

The factors driving the growth of Web portals are primarily rooted in the theories of transaction cost economics and economies of scope, and currently, to a lesser extent on network externalities (see Table 1).

Transaction Cost

The cost that is incurred by a consumer when purchasing a given product is typically not limited to the purchase price.

Typically, it takes time and traversal of a physical distance to complete a purchase. A real estate purchase even requires specialized intermediaries, such as agents/brokers, escrow services, and lawyers. All of these parties add to the expense of the transaction. These additional costs are considered transaction costs (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1975, 1985). Transaction costs may be explicit, such as escrow and legal fees; often though, transaction costs remain unaccounted for, as consumers do not perform any cost accounting. Web portals decrease the time and effort associated with search and for both sides of the market: the buyer and the seller. This gives portals access to two markets. Therefore, this constellation is also referred to as a two-sided market situation (Evans, 2002).

Economies of Scope

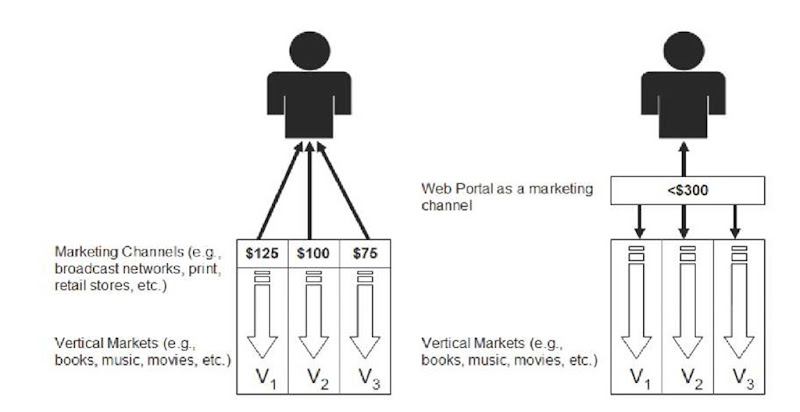

Vendors do not benefit from just the reduction in search costs that portals provide. They also benefit from product scope advantages. Economies of scope are advantages in which the joint cost of two products is less than the sum of the individual costs of each of the products (Teece, 1980). Economies of scope in the portal industry have evolved along two dimensions: horizontal and vertical. Horizontal economies of scope occur when products in two distinct industries are linked through a search result or a portal channel, and can be observed in the way Yahoo! links to Amazon. com for both books and electronics. Vertical economies of scope occur in one given industry and encompass related products, and can be observed when a consumer searches for and purchases a computer on Dell.com’s Web site, and then subsequently purchases peripherals and accessories for that computer on the same Web site. Economies of scope proved to be a compelling reason for many portals to expand across vertical markets. Amazon launched in books and quickly expanded into other categories, such as CDs and consumer electronics. In most vertical markets money is spent on customer acquisition (advertising, free samples, subsidized mobile handsets, etc.). But most vertical markets are selling to the same customer. In essence this customer is acquired multiple times by unrelated businesses, each of which pay a high acquisition price. Portals can establish a relationship with a customer or “acquire” the customer once and then provide leads to different vertical markets. For example, if it takes $125 to acquire a customer in vertical market Vp and $100 for the same customer in vertical market V2, a portal could spend up to $225. If the portal could acquire the customer for less, then it could help sellers in V1 and V2 reduce acquisition cost plus make a profit on its own (see Figure 5).

Table 1. Economic rational of portals

Network Externalities

Both consumers/buyers and sellers/advertisers benefit from positive externalities, in the form of network effects. The literature defines three types of network effects (Farrell & Saloner, 1986; Katz & Shapiro, 1985, 1994): direct effects, in which the number of users within a network directly increases the value of that network (i.e., the more fax machines, the larger the fax user base), indirect effects, in which the adoption of the network is affected by the number of users within the network (i.e., the bigger the share of an operating system, the more attractive it becomes for compatible software, whose availability, in turn, reinforces the appeal of the OS), and post-purchase effects, in which a user will, before buying into a network, take into consideration the size of after-sales services before buying into a network (e.g., an auto brand’s dealership and service center network).

Complexities of Portal Competition

EBay is a good example to illustrate network externalities in digital, interactive channel systems. As EBay’s user base increases in size, it also increases the liquidity of a given product market. This effect increases the value of the service to both sides of the market, the buyer shopping for a particular product, as well as the seller offering this type of product. Amazon, another high-profile digital marketeer and online retailing portal, also benefits from direct network effects. Amazon benefits through the use of consumer profiles. It can recommend products that other consumers with similar profiles have purchased. The higher the sales are, the richer profiles will be, and the more accurate recommendations can be. CNET, yet another Web portal, is also benefiting from its user base through user reviews of products. However, competitive dynamics differ. While EBay and Amazon benefit immediately from sales volume, high traffic is no guarantee that CNET will generate many and useful reviews. Instead, the key to success for CNET is an increase in customer involvement (Schlueter Langdon, 2003b).

By lowering costs for both the buyer and seller, portals have been able to provide all parties with value that is often above and beyond what traditional channels can offer. However, despite these advantages, portals remain subject to threats and opportunities just like other businesses. Specific pitfalls and lessons learned are discussed in a separate article in this publication titled “Portal Economics and Business Models: Pitfalls, Lessons Learned and Outlook.”

Figure 5. The power of profiles: Monetizing value across relationships

KEY TERMS

Business Ecosystem: Used to describe the larger community of individuals and organizations with complementary assets and skills involved in market interaction.

Channel System: A set of intermediaries and their infrastructure linking producers with markets. Few producers sell their goods directly to end users, but rely on intermediaries to perform a variety of activities, including marketing, distribution, and sales. The Internet has enabled digital interactive services and a digital interactive channel system.

Economies of Scope: Describe advantages in which the joint cost of two products is less than the sum of the individual costs of each of the products.

Network Externalities: Describe a change in benefit to one user of a good due to the change of total users of the good.

Softwarization: Describes the process of continuous automation of business activities using computer software and processing power.

Two-Sided Market: Describes a setting in which two distinct groups provide each other with network benefits. The setting can be “viral,” with demand from one group seeding more demand from the other; also called two-sided network.