Homeland security has been defined (Dobbs 2001) as The prevention, deterrence, and preemption of, and defense against, aggression targeted at U.S. territory, sovereignty, population, and infrastructure as well as the management of the consequences of such aggression and other domestic emergencies.

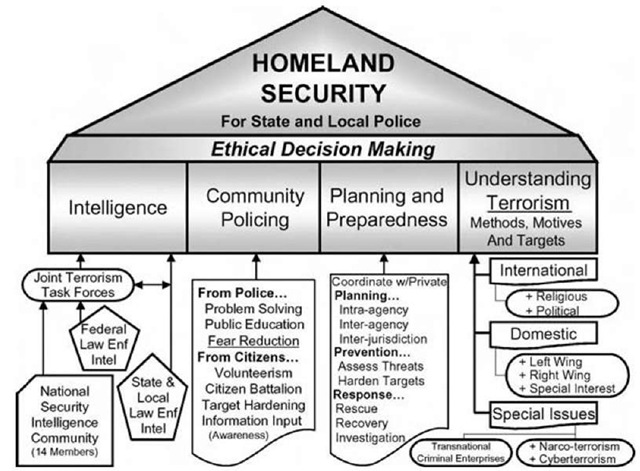

Figure 1 Homeland Security responsibilities for state, local, and tribal police.

As the idea of homeland security has been embraced (often reluctantly) by state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies, a pattern has emerged with respect to the programmatic, training, and policy implications for law enforcement agencies. There are four broad pillars of responsibility that have been embraced by policing as the strategic components of homeland security: intelligence, community policing/ partnerships, planning and preparedness, and understanding terrorism.

There are significant implications of these responsibilities with respect to re-socialization of the police work force, resource development and reallocation, and organizational development that go beyond any change experienced in modern American policing. Each law enforcement agency and community will respond in a different way, depending on the level and nature of the threat inherent in the community characteristics, the political and community mandate with respect to homeland security, the ideology of police leadership on these issues, and the resource capacity of the jurisdiction. Since every community is different, every community must make a self-assessment of how the pillars of homeland security will apply to its law enforcement agency.

Because of the changes brought to contemporary society by the threat of terrorism, new aggressive actions by the law enforcement and intelligence communities have been undertaken. Yet, an essential element of maintaining a secure homeland is to protect the constitutional principles that the United States is founded on. Hence, an ethical (and ideological) dilemma has emerged. Because of this dilemma, the overriding capstone to the four pillars of homeland security is to ensure adherence to our founding principles via ethical and judicious decision making by law enforcement personnel. If these principles are lost, so is our homeland.

The Pillars

Law Enforcement Intelligence

The National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan (NCISP) states that every law enforcement agency, regardless of size, should have an intelligence capacity. This means that law enforcement agencies need to have, at the least, a person who has been trained to understand the guidelines for collecting raw information for the intelligence process, proper means of storing and reviewing data in intelligence records systems, and rules for disseminating intelligence and sensitive information. That person should also have access to critical information systems, such as the FBI’s Law Enforcement Online (LEO) and/or the Regional Information Sharing System’s (RISS) secure system RISS.net.

Intelligence is critical to understanding the nature of terrorists’ threats, identifying local suspects and local targets, and determining intervention and prevention strategies. Intelligence is the currency by which homeland security is managed within a jurisdiction. The need to develop and share intelligence is unequivocal for the success of the homeland security initiative.

Community Policing

Inherent to the success of identifying threats within a jurisdiction is to have an effective, trusted line of communication between citizens and the law enforcement agency. Hence, the strong foundation that has been laid in America’s law enforcement agencies with community policing as a tool to reduce disorder and prevent crime can be translated to counterterrorism and homeland security. Law enforcement agencies must educate citizens about the signs and symbols of terrorism as well as provide direction on what to do when suspicious activity is observed. Lessons learned in Israel, Turkey, and the United Kingdom have found that good community partnerships can be critical in preventing terrorism. Indeed, each of these countries has policing programs with the community designed specifically for counterterrorism.

Planning and Preparedness

The primary goal of intelligence in homeland security is to prevent a terrorist attack. Lessons learned from crime prevention have shown us that while many crimes can be prevented, they cannot all be prevented. The same is true with terrorism. Hence, part of the homeland security responsibility is to ensure that comprehensive and effective plans are in place to respond to a terrorist attack in a manner that will both facilitate the safety of the community and permit a comprehensive investigation in order to identify and prosecute the offenders. As a result, the law enforcement agency must develop coordinated plans and incident management protocols and establish effective working relationships with neighboring law enforcement agencies as well as the first responder community (Bea 2005).

Understanding Terrorism

Terrorist threats emerge from both ends of the political spectrum and can be domestic or international in nature. History has shown criminally extremist acts committed by such diverse groups as al-Qaeda, the Earth Liberation Front, and religious extremists. Regardless of their cause, there is a foundation of information that is consistent among all groups— each has motives, methods, and targets. For a law enforcement agency to be most effective in identifying the signs and symbols of terrorism, personnel must understand the motives, methods, and targets of the group(s) that threaten the community. This permits officers—and citizens—to focus their attention and more readily identify behaviors and circumstances that are truly suspicious. Understanding terrorism plays critical roles for successful intelligence and community policing.

Translating Responsibilities to Police Policy

Overarching the four pillars of responsibility for homeland security are critical organizational functions that must be addressed.

Information Management

There is a great deal of information associated with all policing tasks; homeland security is no different. Information management includes a broad array of responsibilities ranging from public education— which can contribute to fear reduction or aid in identifying threats—conducting threat assessments, establishing effective communications between agencies, and managing complaints or tips. This last element has significant implications and can be a labor-intensive investment for the organization.

For example, during the anthrax scare occurring shortly after the 9/11 attacks, police agencies across the United States received a large number of calls about potential anthrax. Fortunately, almost all of those calls were unfounded; nonetheless, they required some type of response from the police. Important questions emerged:

• How should an agency respond when the probability of a problem is extraordinarily low?

• Can the police agency afford to simply dismiss the call?

• If the agency responds, is there a mechanism for filtering which calls will receive a response?

• How would such a determination be made?

• What are the implications of not responding to a complaint that turns out to be valid?

• What will be the cost of responding and what, if any, other police responsibilities would have to be reduced in order to manage such calls, particularly in a time of crisis?

Although tempting, one has to be careful about dismissing a call. As an example, during the course of the sniper shootings occurring in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia during October 2002, a tip line was created that generated tens of thousands of calls. It was later learned that one of the suspects, John Muhammad, had actually called the tip line twice and the call was dismissed by an overwhelmed staff member. If contact had been established sooner, would lives have been saved? The answer is unknown; however, the point remains: A mechanism must be established to manage information.

Physical Responsibilities

When potential targets are identified within a community, there are inherent obligations to harden and protect those targets. In some cases, such as an electrical power generating plant, the target will typically have private security with whom the police must work to ensure that protection of the target is maximized. In other cases, such as a municipal water treatment plant, the only security available may have to be provided by the police. Moreover, if the threat to those targets should be heightened, the police agency must then become more vigilant in physical protection, often even supplementing private security forces.

When the wide range of potential critical infrastructure targets within a community are considered, then the impact of potential security responsibilities becomes even more profound. Not only are security responsibilities inherently labor intensive (and hence costly), but when personnel are at a security assignment, there are typically no other policing duties they can fulfill. As such, the options include the following:

• Minimize other police activities (for example, not respond to every call for service, decrease investigative follow-ups, reassign officers working in the schools, and so on).

• Pay overtime to officers to work security assignments.

• Contract with a private security firm to work the security assignments.

• Develop a volunteer force of citizens to supplement police security responsibilities.

• Employ a combination of these methods, depending on the nature or seriousness of the threat and the duration of the threat period.

Regardless of the option, there are significant resource implications for the police response. Law enforcement leaders must ask the question “How will we fund this?”

Procedural Responsibilities

Homeland security requires that there simply be ”a number of things which must be done” to accomplish the responsibilities discussed so far. These include the following:

• Developing and implementing a terrorism investigative capability

• Developing, teaching, and implementing prevention strategies

• Developing, continually reviewing, and practicing response plans

• Developing interagency planning responsibilities and agreements, with constant monitoring of changes that need to be made in such agreements as a result of fluctuations in the budget and agency staffing and the changing characteristics of the jurisdictions involved

As in the previous cases, the resource implications are significant, particularly for staff time.

Two factors cannot be stressed enough: (1) Each of these responsibilities has significant resource implications. (2) These are new responsibilities not previously bestowed on state, local, and tribal law enforcement. Thoughtful planning is essential for success to be achieved without undue sacrifice to other policing obligations.

The Impact on State, Local, and Tribal Governments

This is an uncharted journey that requires research, careful thought, and effective planning. As noted previously, homeland security is an added police responsibility with two broad concerns: policy and resources. An example will illustrate the issues:

• Police departments need to make policies on how to respond when the Homeland Security Advisory System (HSAS) alert status increases. If, for example, the alert status moves from yellow to orange, what does this mean to a police agency? Are police and emergency services placed on a standby status? If so, are there overtime costs associated with this? Are duty hours extended? If so, there are further salary implications.

• As a result of the higher alert level, will personnel be reassigned for contingency purposes? If so, what are the implications for managing calls for service? For example, during a high alert status will “priority three” calls be ignored because of staffing implications?

• What equipment—vehicles, radios, hazardous materials (hazmat) tools, and so forth—is needed and how will it be deployed? How will operational priorities change? For example, will officers be directed to be more proactive in stopping vehicles of people thought to be involved in terrorism? If so, the obvious concern is allegations of racial profiling and deprivation of civil rights.

This simple, yet realistic, example illustrates that the impact of homeland security on local police policy and resources can be dramatic. Expanding this line of thought, the National Preparedness Goal has significant implications for training, staffing, deployment, and resource allocation. Importantly, police administrators should fully analyze the expectations and role of their agencies in homeland security. This is a laborious, and somewhat subjective, process, yet it is essential.

Second, the department must conduct an operations analysis to understand its capacity to fulfill the homeland security mission. Were plans executed as anticipated? Were responses effective? Was intelligence accurate? Self-directed evaluations provide important insight for refining plans and responses.

Third, methods must be explored to determine how these homeland security needs may be met (for example, exploring grants and creative funding, partnering with agencies on a regional basis, public-private partnerships, working with community service groups, and developing a volunteer program). Of course, these must also consider the balance between homeland security with other police responsibilities.

Fourth, once methods are determined, they must be operationalized. This includes establishing a command structure, identifying responsibilities, developing operating policies and procedures, and implementing plans.

Fifth, implementation begins with training and education. Not only must skills be developed (that is, training), but there must also be an understanding of the broader issues. This includes ensuring that reasonable, consistent decision-making skills have been inculcated in personnel (that is, education). Finally, the homeland security initiative must be implemented and evaluated. Fundamentally, the question to be answered is, ”Did it work?”

In determining if the plan ”worked,” it must be recognized that homeland security has implications for changing all aspects of the police organization. Any type of change has implications for resources, management, the development of new expertise, defining accountability, and evaluating activities/initiatives to ensure that new plans and initiatives are meeting expectations. Examples of changes include the following:

Line level officers—greater awareness of the potential for terrorism, including scanning the community for ”signs” or indicators of threats, establishing relations and communications with segments of the community that may have some relationship with extremist groups, and creating a new public dialogue for public education and fear reduction associated with terrorism.

Investigations—new knowledge and responsibilities for detectives who must develop expertise for investigating the different types of extremist groups that may pose a threat to the community. This includes developing confidential informants, understanding local dynamics of criminal extremism, and developing the ability to infiltrate group(s) in an undercover capacity.

Intelligence—a more proactive intelligence capability within the police department to address homeland security issues, including more frequent and more substantive relationships with multiple agencies at all levels of government, including the FBI Field Intelligence Groups (FIG), Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTF), and intelligence fusion centers.

Public/private partnerships—required to maximize the protection of critical infrastructure as well as to coordinate resources and capabilities for a response to a terror attack.

Multiagency cooperation—both within the jurisdiction and between neighboring jurisdictions. The police agency must revisit formal relationships—such as mutual aid pacts or memoranda of understanding—to have a clear understanding of relationships, authority, responsibility, resource sharing, and types of aid that will be provided in prevention, planning, and response to terrorism.

First responders—ensuring that those who would respond first to a terror attack have the equipment, knowledge, and expertise to effectively manage virtually any type of terror scenario that could be anticipated. This requires a significant investment in training and equipment and cannot be strictly limited to a unique team since the first responders will frequently be patrol officers who, at the minimum, will need to render aid and manage the scene until specialists arrive. Hence, first responder training will need to include varied levels of expertise, ranging from those who are truly the first to arrive at a scene and need to manage the immediate emergency to the incident commander who will ensure stability of the scene, rescue, recovery, and investigative/evidence gathering responsibilities.

Prevention/target hardening— developing greater attention, knowledge about, and expertise in prevention and the hardening of potential terrorist targets. This requires broadened expertise and time, which translates into a greater number of dedicated staff hours to meet these responsibilities.

Training—new training must be provided at virtually all levels of the organization to meet several purposes. These include providing baseline information about threats, issues, plans, and responsibilities, providing more detailed/intensive training to develop new expertise in a wide range of areas from intelligence to investigations, and managing a response to weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

Planning—both long-range and short-range plans must add a new dimension not previously included in the police planning equation: having a greater sense of urgency when considering growing and changing terrorism threats to a community and how the law enforcement agency will respond to those threats.

Questions include the following:

• Are new businesses on the horizon that may be targets of any type of terrorist group?

• Is the demography of the community or region changing in a way that may suggest new targets or attract people who may be involved in terrorism?

• Are there changes occurring within the design of the community that will change a response plan?

• Are new resources—such as a hospital—emerging within the community that need to be included within the critical incident plan?

The implications of these activities can be dramatic. They all require two things that are inherently in short supply: money and people. There will be some financial support available from the federal government for the purchase of equipment and training personnel; however, these represent only a fraction of the costs. The personnel costs of learning to use the new equipment and to attend the training can be significant. Moreover, addressing these new homeland security responsibilities is more than a simple ”add on” to the police department. Decisions have to be made about how the department will balance homeland security with other responsibilities:

• Will there be fewer burglary follow-up investigations in order to devote more time to investigating extremist threats?

• Will less emphasis be devoted to gangs or drug enforcement in order to develop an intelligence expertise related to terrorism?

• Will less emphasis be placed on traffic enforcement and more emphasis on developing a comprehensive expertise in first response?

• Will less public education be devoted to fear of crime and more public education be devoted to fear of terrorism?

• Will citizen volunteers spend less time in assisting parking enforcement and more time observing critical infrastructure facilities looking for security lapses?

The answers to these questions, and others, must be unique to a community, as will be the method of paying for the added homeland security activities.

A Local Police Response to Federal and Public Demands

The impact of the added homeland security responsibility on police departments since 9/11 is substantial. A number of agencies—such as the police departments in New Orleans and Austin as well as sheriffs’ departments, such as in Orange County, Florida, and Harris County, Texas— have created homeland security units. Many other agencies have reassigned personnel to new homeland security-related areas as well as purchased equipment and increased training. (For the most part, the threat of terrorism has not translated into the hiring of more officers.) While efforts vary according to each community’s resources and perceived vulnerability, among the steps local law enforcement agencies have taken are the following:

• Strengthened liaisons with federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies, fire departments, emergency planners, emergency responders, and private businesses representing critical infrastructure or unique targets

• Refined their training and emergency response plans to address terrorist threats, including attacks with chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) weapons

• Increased patrols and strengthened barriers around landmarks, places of worship, ports of entry, transit systems, nuclear power plants, and other “hard” targets that include utilities, telecommunications, key transportation facilities, and government buildings

• Ensured that public speeches, parades, and other public events have greater police involvement in planning and, as appropriate, greater police presence

• Created new counterterrorism initiatives and reassigned officers to counterterrorism and/or intelligence from other assignments such as drug enforcement or gangs

• Employed new technologies such as devices that can test for and sense chemical and biological substances

The benefit of these initiatives is that police agencies are taking positive steps to deal with terrorism threats and make their communities safer. The problem, however, is that all too often these steps have been taken based upon assumptions of threats, not careful threat assessments related to the types of groups that pose threats, the character of those groups’ targets, the character of attack from those groups, and the probability of attack. In other words, most of these initiatives have been reactive and based on assumptions, rather than being the product of planning based on intelligence.

Federal, State, and Local Cooperation: The Joint Terrorism Task Forces

One aspect of law enforcement that has evolved significantly is local police involvement in the Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTF). The concept for these joint task forces, combining federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement capabilities, was first used by the FBI in New York City in 1979, due to an overwhelming number of bank robberies. Because this approach proved to be a valuable investigative tool, it was applied to the counterterrorism program in 1980 when the first JTTF was established in New York. This was the direct result of the increasing number of terrorist bombings in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which mandated an immediate and coordinated response. The JTTF’s have a wide variety of law enforcement agencies at all levels of government—FBI, ATF, Secret Service, immigration and customs enforcement, U.S. Marshals, and other federal organizations as well as state, county, municipal, and tribal police organizations within a defined geographic area. There are currently more than a hundred JTTFs operating out of all FBI field offices and many FBI resident agency offices.

The unfunded mandate of homeland security has broad implications that reach beyond protecting our communities from terrorist attacks. How will it affect yours?