The question of whether firearms availability helps cause homicides is important for two reasons. First, scholars want to understand why homicide rates differ over space and time, and access to guns may partly account for the patterns. Firearms are then one of many factors that might explain variations in the rates, making the relationship a matter of theoretical interest.

Second, and more controversially, the link between firearms and homicides has a bearing on gun control policies. If widespread gun ownership promotes lethal violence, stricter regulations may lead to fewer murders. If gun availability does not affect homicides, gun control laws will be of only symbolic value. Knowing that people have ready access to guns might even deter some potential killers, and tighter restrictions could endanger public safety.

No doubt exists that many murderers use firearms—usually handguns—to commit their crimes. Currently, guns are the instruments of death in about 65% of homicides in the United States. In 2002, firearms accounted for more than nine thousand killings in the nation, with seven thousand of these due to handguns (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2002a).

Homicides of police officers are even more likely to involve firearms than homicides of other citizens. Between 1993 and 2002, gunshot wounds claimed the lives of 93% of all law enforcement officers murdered in the line of duty (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2002b). Lester (1987) shows that the risk of firearm murder for a city police officer rises with the gun murder rate in the city at large.

Despite these figures, it does not necessarily follow that gun ownership levels influence homicidal violence. Homicide rates may depend mostly on the number of persons who wish to kill. If guns were not handy, murderers might simply switch to other weapons.

Two issues have received special attention in studying the impact of gun availability on murder. The first of these is a theory to explain how firearm ownership levels might affect homicide rates. The second is how much association exists between the two variables.

Weapon Choice Theory

The mechanism most often used to link firearm ownership to homicides is the weapon choice theory proposed by Zimring (1968; Zimring and Hawkins 1997). The theory rests on the idea that murderers often do not set out with a desire to kill. A robbery goes awry, for example, or an argument spirals into violence. The offender attacks the victim with whatever weapon is at hand, ending the assault after causing injury. The victim’s fate then depends heavily on the weapon. If the weapon is highly lethal, it is more likely that the victim will die.

According to the weapon choice theory, shootings are more deadly than are other methods of attack. If fewer guns were available, the offender would not be as likely to have one and would use a less effective weapon instead, reducing the chances of death.

The theory assumes that people who are bent on killing can find guns if they make enough effort. Yet they must make more effort when firearms are less available, and fewer assailants will have a gun nearby if general levels of ownership are low.

The weapon choice theory suggests that lower rates of firearm ownership will not change the total amount of criminal violence. Violent persons can, and will, use other weapons. Still, if these weapons are not as dangerous as guns, assaults will not as often end as murders.

Evaluation of the Weapon Choice Theory

The weapon choice theory claims that guns are especially lethal instruments and that homicides are often unintentional. There is little question about the first point. In Zimring’s (1968) study, the death rate for persons attacked with guns was five times higher than the death rate for persons attacked with knives.

It is not as easy to estimate how many murderers lack a firm wish to kill. This depends on motivations, and motivations can be elusive. Scattered evidence does suggest that criminal shootings are often a matter of chance. In one research project, Wright and Rossi (1986) surveyed a sample of felons about the weapons they used. Of the felons who had fired a gun during a crime, only 23% said that they had originally planned to do so.

These and other data measure motivations after the fact, and this part of the theory probably will remain arguable. The theory also does not consider the role that armed citizens might play in discouraging violent attacks. Due to issues such as these, the effect of firearm ownership on homicides must be found empirically.

Evidence on the Relationship between Firearm Availability and Homicides

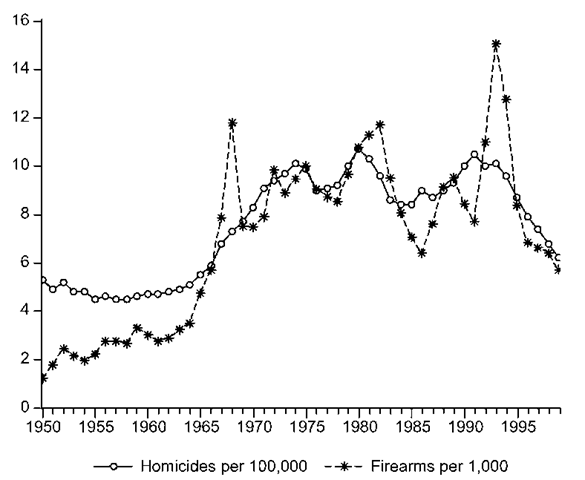

Figure 1 plots homicides per hundred thousand residents of the United States and new firearms offered for sale per thousand residents. The data are annual, between 1950 and 1999. Both variables follow similar trends, with changes in the homicide rate roughly mirroring changes in the stock of new guns.

This comparison suggests that the relationship between firearm ownership and homicides deserves additional study. By itself, however, it is not enough to show that rising levels of gun availability lead to increases in murder. This is so for three reasons.

First, the number of firearms in private hands is difficult to measure. Estimates of available guns in the United States vary widely, and useful figures do not exist for areas smaller than the entire nation. Figure 1 uses new guns, and homicides may also involve firearms that people obtained in earlier years. Guns wear out over time, and no one knows how many older weapons remain in service.

Second, firearm ownership may depend partly on the same social conditions that generate homicide rates. To take only one example, attitudes favorable to violence may lead to higher levels of gun access and also to higher rates of murder. As far as this is so, the association between gun ownership and homicides exists only because of common causes.

Figure 1 Homicides per hundred thousand and new firearm per thousand in the United States, 1950-1999.

Third, much firearm ownership may be a response to crime. That is, people may obtain guns to protect themselves as homicide rates rise. Then the two variables will be correlated because homicides help cause the demand for guns.

Many studies have considered the link between gun availability and homicides, and most have tried to deal with one or more of these problems. No study has satisfied all critics, and not all findings are in accord (Hemenway 2004; Kleck 1997). The bulk of this research nevertheless points in the same direction.

Studies of the Entire United States or of U.S. States

Several studies examine the stock of firearms and homicide rates in the entire United States or in individual states. As in Figure 1, they measure gun availability using data on firearm sales or production.

Examples are Kleck (1984), Magaddino and Medoff (1984), and Sorenson and Berk (2001). Each study included controls for common causes of gun availability and murders. Kleck and Magaddino and Medoff also considered whether homicide rates affected ownership levels. Except for Kleck, these researchers all found that increases in homicides accompanied increases in the supply of guns.

Studies that use production or sales figures must allow for the average lifetime of a firearm. Any estimate is no more than a guess, and errors here may affect the conclusions. In addition, murder rates are highest in large cities, but firearms are most common in rural areas. Findings for the nation or states may then rest on false correlations between crimes committed in urban areas and gun ownership in rural areas.

Studies of Cities and Counties in the United States

A second set of studies considers the association between firearms and homicides in U.S. cities or counties. These smaller areas avoid some of the problems with using the nation or states, but no accurate counts of gun owners exist for them. The city and county studies must therefore gauge firearm availability from indirect indicators. Common indicators include the fraction of robberies committed with guns, the fraction of suicides committed with guns, and sales of gun-oriented magazines. The values of these indicators presumably increase with levels of ownership.

Research that uses this approach includes Cook (1979), Duggan (2001), Kleck and Patterson (1993), and McDowall (1991). Each study controlled for common causes of firearm ownership and homicide, and Duggan, Kleck, and Patterson, and McDowall allowed for a mutual relationship between the two variables. Cook found that city robbery-murder rates rose with the volume of available guns. Duggan found that availability predicted homicide rates in a sample of counties, and McDowall found that availability influenced homicide rates in Detroit. In contrast, Kleck and Patterson concluded that gun ownership was unrelated to the murder rates of the cities that they examined.

These studies assume that firearm availability in a city or county depends on how often its residents use guns. Yet no indicator of use will be a completely satisfactory measure. One limitation is that most indicators focus on violent acts, and so they may have only a weak relationship to the number of responsible owners.

Employing a different strategy, a highly publicized study by Lott (2000) compared homicide rates before and after states relaxed their laws on carrying concealed weapons. Lott found that homicides fell after the laws began, and he argued that this was due to easier access to guns by honest citizens. Yet his study did not measure actual changes in available guns, and critics have serious doubts about its conclusions (Hemenway 2004).

International Studies

A third approach compares murder rates in nations that differ in their amount of access to firearms. In one study of this type, Killias (1993) used survey data to estimate gun ownership in fourteen nations. Ownership levels ranged from very high (the United States) to very low (the Netherlands), and homicides increased with ownership. Hemenway and Miller (2000) likewise correlated measures of firearm availability with homicide rates in twenty-six nations. As with Killias, they found that nations with higher gun availability had higher homicide rates.

Killias, von Kesteren, and Rindlisbacher (2001) used the same procedures as Killias, but they expanded the number of nations they examined to twenty-one. Unlike the original Killias study, their results showed little connection between gun ownership and homicide rates. This difference was mainly due to the presence of Estonia in the second study. Estonia had low levels of ownership, and its crime rates had surged after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

The fragile findings show a general problem with the international research: Only a few observations exist, and unusual cases can skew the results. Culture and history also complicate the comparisons, because both gun ownership and homicide are due in part to features unique to a nation. These features are hard to measure, and the small number of countries makes it difficult to control them.

Magnitude and Implications of the Relationship

Although the findings are not entirely consistent, studies using different methods largely agree that homicide rates rise as firearms become more available. Importantly, however, the sizes of the associations are often small. McDowall (1991) estimated that Detroit’s 1986 homicide rate would have been 4% lower if access to guns had been at 1980 levels. Yet even then, the city’s 1986 rate would have been a 45% increase above its 1980 value. Cook’s (1979) results showed that a 10% decrease in gun availability would reduce a city’s rate of robbery-murder by only 4%. This broadly agrees with Duggan (2001), who found that a 10% drop in county gun ownership would reduce total homicide rates by 2%.

Firearm availability may therefore have only a relatively modest impact on murder rates. The United States has many guns, and only a tiny fraction of owners use them in criminal violence. This makes it hard to find effective prevention policies, and it ensures that restrictive gun control laws will be controversial.

FIREARMS: GUNS AND THE GUN CULTURE

Guns are versatile tools, useful in providing meat for the table, eliminating varmints and pests, providing entertainment for those who have learned to enjoy the sporting uses, and protecting life and property against criminal predators, so their broad appeal is not surprising (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002). They are an especially common feature of rural life, where wild animals provide both a threat and an opportunity for sport. As America has become more urban and more violent, however, the demand for guns has become increasingly motivated by the need for protection against other people (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002).

Gun enthusiasts are sometimes portrayed by the media as ”nuts,” ”sexually-warped fetishists,” ”vigilantes,” and ”anti-citizens” (Kates 1997, 9). Research on gun owners, however, reveals that they are not more likely to be racist, sexist, or violence prone than non-gun owners (Kleck 1991). Only a small fraction of privately owned firearms are ever involved in crime or unlawful violence (Kleck 1991). For many Americans, guns are an integral and essential part of their identity. Guns are revered as a liberator and guarantor of freedom; guns symbolize independence and self-reliance (Slotkin 2003). For many young men, guns can be a symbol of masculinity, status, aggressiveness, danger, and arousal (Fagan and Wilkinson 1998). Not surprisingly, gun owners are more likely to approve of ”defensive force” to defend victims when compared to their non-gun owning counterparts (Kates 1997).

The gun culture plays a central role in the contentious American debate on guns and gun control. Three key areas provide important insights on the role the gun culture plays in the larger gun debate: gun ownership patterns, the Second Amendment and the ”rights and responsibilities” perspective, and the uses of guns for self-defense.

Patterns of Gun Ownership

The 1994 National Survey of the Private Ownership of Firearms (NSPOF) by the National Opinion Research Center found that 41% of American households included at least one firearm. Approximately 29% of adults say that they personally own a gun. These percentages reflect an apparent decline in the prevalence of gun ownership since the 1970s (Cook and Lud-wig 1996). While the prevalence of gun ownership has declined, it appears that the number of guns in private hands has been increasing rapidly. Since 1970, total sales of new guns have accounted for more than half of all the guns sold during this century, and the total now in circulation is on the order of two hundred million (Cook and Ludwig 1996).

How can this volume of sales be reconciled with the decline in the prevalence of ownership? Part of the answer is in the growth in population (and the more rapid growth in the number of households) during this period; millions of new guns were required to arm the baby boom cohorts. Beyond that is the likelihood that the average gun owner has increased the size of his or her collection (Wright 1981). The NSPOF estimates that gun-owning households average 4.4 guns, up substantially from the 1970s (Cook and Ludwig 1996). Kleck (1991), however, suggests that the true prevalence trended upward during the past couple of decades and that survey respondents have become increasingly reluctant to admit to gun ownership during this period.

One addition for many gun-owning households has been a handgun. The significance of this trend toward increased handgun ownership lies in the fact that while rifles and shotguns are acquired primarily for sporting purposes, handguns are primarily intended for use against people, either in crime or self-defense. The increase in handgun prevalence corresponds to a large increase in the relative importance of handguns in retail sales: Since the early 1970s, the handgun fraction of new-gun sales has increased from one-third to near one-half (Cook 1993). The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) estimated that one out of every two new guns sold in the United States in the early 1990s was a handgun. In the late 1990s, the handgun share of all new gun sales decreased to about 40% (ATF 2000).

Some of the increased handgun sales have been to urban residents who have no experience with guns but are convinced they need one for self-protection, as suggested by the surges in handgun sales after the Los Angeles riots and other such events (Kellerman and Cook 1999). But while the prevalence of handgun ownership has increased substantially during the past three decades, it remains true now as in 1959 that most who possess a handgun also own one or more rifles and shotguns. The 1994 National Survey of the Private Ownership of Firearms found that just 20.4% of gun-owning individuals have only handguns, while 35.6% have only long guns and 43.5% have both.

These statistics suggest that people who have acquired guns for self-protection are for the most part also hunters and target shooters. Indeed, only 46% of gun owners say that they own a gun primarily for self-protection against crime, and only 26% keep a gun loaded. Most (80%) grew up in a house with a gun. The demographic patterns of gun ownership are no surprise: Most owners are men, and the men who are most likely to own a gun reside in rural areas or small towns and were reared in such small places (Kleck 1991). The regional pattern gives the highest prevalence to the states of the Mountain Census Region, followed by the South and Midwest. Blacks are less likely to own guns than whites, in part because the black population is more urban. The likelihood of gun ownership increases with income and age.

The fact that guns fit much more comfortably into rural life than urban life raises a question. In 1940, 49% of teenagers were living in rural areas; by 1960, that had dropped to 34% and by 1990, to 27%. What will happen to gun ownership patterns as new generations with less connection to rural life come along? Hunting is already on the decline: The absolute number of hunting licenses issued in 1990 was about the same as in 1970 despite the growth in population, indicating a decline in the percentage of people who hunt (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002). Confirming evidence comes from the National Survey of Wildlife-Associated Recreation, which found that 7.2% of adults age sixteen and above were hunters in 1990, compared with 8.9% in 1970. This trend may eventually erode the importance of the rural sporting culture that has dominated the gun ”scene.” In its place is an ever greater focus on the criminal and self-defense uses of guns (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002).

The Second Amendment and the ”Rights and Responsibilities” Perspective on Guns

Very much in the foreground of the debate on guns and gun control lies the Second Amendment, which states, ”A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The proper interpretation of this statement has been contested in recent years. Scholars arguing the constitutionality of gun control measures focus on the militia clause and conclude that this is a right given to state governments (Vernick and Teret 1999). Others assert that the right is given to ”the people” rather than to the states, just as are the rights conferred in the First Amendment, and that the Founding Fathers were very much committed to the notion of an armed citizenry as a defense against both tyranny and crime (Kates 1992; Halbrook 1986).

The Supreme Court has not chosen to clarify the matter, having ruled only once during this century on a Second Amendment issue, and that on a rather narrow technical basis. William Van Alstyne (1994) argues that the Second Amendment has generated almost no useful body of law to date, substantially because of the Supreme Court’s inertia on the subject. In his view, Second Amendment law is currently as undeveloped as First Amendment law was up until Holmes and Brandeis began taking it seriously in a series of opinions in the 1920s. Indeed, no federal court has ever overturned a gun control law on Second Amendment grounds.

Regardless of the concerns that motivated our founding fathers in crafting the Bill of Rights, the notion that private possession of pistols and rifles is a protection against tyranny may strike the modern reader as anachronistic—or perhaps all too contemporary when recent events with such groups as the Branch Davidians and the Aryan Nation are considered. Much more compelling for many people is the importance of protecting the capacity for self-defense against criminals. Some commentators go so far as to assert that there is a public duty for private individuals to defend against criminal predation, now just as there was in 1789 (when there were no police).

The idea that citizens have responsibility for their own self-defense is now widely embraced by police executives and is central to the ”community policing” strategy, which seeks to establish a close working partnership between the police and the community. But the emphasis in this approach is on community-building activities such as the formation of block watch groups or neighborhood patrols, rather than on individual armaments. The argument is that if all reliable people were to equip themselves with guns both in the home and out, there would be far less predatory crime (Snyder 1993; Polsby 1993).

Other commentators, less sanguine about the possibility of creating a more civil society by force of arms, also stress the public duty of gun owners, but with an emphasis on responsible use: storing them safely away from children and burglars, learning how to operate them properly, exercising good judgment in deploying them when feeling threatened, and so forth (Karlson and Hartgarten 1997). In any event, the right to bear arms, like the right of free speech, is not absolute but is subject to reasonable restrictions and carries with it certain civic responsibilities. The appropriate extent of those restrictions and responsibilities, however, remains an unresolved issue.

Self-Defense Uses of Guns

While guns do enormous damage in crime, they also provide some crime victims with the means of escaping serious injury or property loss (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002). The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) is generally considered the most reliable source of information on predatory crime, since it has been in the field for more than two decades and incorporates the best thinking of survey meth-odologists. From this source it would appear that use of guns in self-defense against criminal predation is rather rare, occurring on the order of a hundred thousand times per year (Cook, Ludwig, and Hemenway 1997).

Of particular interest is the likelihood that a gun will be used in self-defense against an intruder. Cook (1991), using the NCVS data, found that only 3% of victims were able to deploy a gun against someone who broke in (or attempted to do so) while they were at home. Since 40% of all households have a gun, it is quite rare for victims to be able to deploy a gun against intruders even when they have one handy.

Gary Kleck and Marc Gertz (1995) have suggested a far higher estimate of 2.5 million self-defense uses each year and conclude that guns are used more commonly in self-defense than in crime. However, Cook, Ludwig, and Hemenway (1997) have demonstrated that Kleck and Gertz’s high estimate may result from problems inherent in their research design. There is also no clear sense of how many homicides were justifiable in the sense of being committed in self-defense (Kleck 1991).

Of course, even if we had reliable estimates on the volume of such events, we would want to know more before reaching any conclusion. It is quite possible that most ”self-defense” uses occur in circumstances that are normatively ambiguous: chronic violence within a marriage, gang fights, robberies of drug dealers, or encounters with groups of young men who simply appear threatening (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002). In one survey of convicted felons in prison, the most common reason offered for carrying a gun was self-defense (Wright and Rossi 1986); a similar finding emerged from a study of juveniles incarcerated for serious criminal offenses (Smith 1996). Self-defense conjures up an image of the innocent victim using a gun to fend off an unprovoked criminal assault, but in fact many ”self-defense” cases may not be so commendable (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002).

The intimidating power of a gun may help explain the effectiveness of using one in self-defense. According to one study of NCVS data, in burglaries of occupied dwellings only 5% of victims who used guns in self-defense were injured, compared with 25% of those who resisted with other weapons (Cook 1991). Other studies have confirmed that victims of predatory crime who are able to resist with a gun are generally successful in thwarting the crime and avoiding injury (Kleck 1988; McDowall, Loftin, and Wiersema 1992). But the interpretation of this result is open to some question. Self-defense with a gun is a rare event in crimes such as burglary and robbery, and the cases where the victim does use a gun differ from others in ways that help account for the differential success of the gun defense. In particular, other means of defense usually are attempted after the assailant threatens or attacks the victim, whereas those who use guns in self-defense are relatively likely to be the first to threaten or use force (McDowall, Loftin, and Wiersema 1992). Given this difference in the sequence of events, and the implied difference in the competence or intentions of the perpetrator, the proper interpretation of the statistical evidence concerning weapon-specific success rates in self-defense is unclear (Cook 1991).

The ability of law-abiding citizens to be armed in public has been facilitated in recent years by changes in a number of state laws governing licensing to carry a concealed weapon, and by 1997 a majority of states had liberal provisions that enable most adults to obtain a license to carry firearms. A controversial study (Lott and Mustard 1997; Lott 2000) found evidence that states that liberalized their concealed-carry regulations enjoyed a reduction in violent crime rates as a result, presumably because some would-be assailants were deterred by the increased likelihood that their victim would be armed. However, other researchers, using the same data, conclude that there is no evidence of a deterrent effect (see Ludwig 2000 for a comprehensive review).

Many analysts are also skeptical of the deterrent effects of easing concealed-carry laws because the prevalence of carrying by likely victims is too small (less than 2% of adult residents) to generate the very large effects on homicide and rape suggested by the Lott studies (Cook, Moore, and Braga 2002). Given the available evidence, it is difficult to make firm conclusions about the effects of these laws on preventing crime.

Technological Developments

Firearm technology changed dramatically during the nineteenth century. The standard handgun in the early 1800s was a single-shot flintlock pistol loaded from the muzzle using black powder and a lead ball. These were available wrapped together in the form of a paper cartouche. The priming charge was poured into a small pan covered by a steel frizzen that sat in the arcing path of the spring-loaded cock. The cock grasped a piece of flint that, when the trigger was pressed, sprang forward to strike the steel frizzen to produce a shower of sparks. During the second quarter of the 1800s, the pressure-sensitive percussion cap containing fulminate of mercury came into use, and the flintlock gradually gave way to the new percussion lock. Importantly, this small explosive cap made it possible for Samuel Colt to design his multishot ”revolver.”

Colt’s Paterson model revolver and other ”cap-and-ball” style handguns of this general design had revolving cylinders typically featuring five or six chambers that could be loaded with powder and ball and left capped for immediate use. Prior to this development there was the major impediment to sustained and effective self-defense in that one had to have handy as many pistols as one might desire available shots. The revolver’s half-dozen shots therefore was a tremendous leap forward in a person’s capacity to counter an assault.

The next major development displaced the old technology of loose powder and lead ball, as well as the handier paper cartouche, through the introduction of the durable and far more reliable metallic cartridge. The self-contained metallic cartridge accomplishes several important ends; it confines the powder in its cavity and has its ignition source on one end in the form of a primer fitted into the base and at the other end, its bullet. Metallic cartridges are relatively impervious to moisture that always had plagued gunpowder.

The next major development was to bore the chambers of the revolver’s cylinder straight through to accommodate metallic cartridges being inserted from the rear. Perhaps the most popular example is Colt’s Firearms’ Peacemaker.45 caliber introduced in 1873, which many consider to have been the standard of its day. For the military and police use, however, the ”single-action” Peacemaker that was thumb-cocked prior to each shot would soon give way to double-action revolvers that had a second mechanism for simply pressing the trigger to cock and fire the revolver. These revolvers also would come to feature a swing-out cylinder to facilitate easier and quicker loading.

The metallic cartridge’s final major development came around 1900, when ”smokeless” propellants began to displace the black powder that discharged thick smoke that grew thicker with subsequent shots. This metallic cartridge was the catalyst for another technological leap around the turn of the century: the semiautomatic handgun. This type of handgun, also referred to as ”self-loading,” holds its ammunition not in a revolver cylinder but, rather, stacked inside a spring-loaded magazine that is then inserted into the frame of the pistol. During the span of the nineteenth century, the single-shot flintlock pistol that might be loaded and fired two to perhaps three times a minute gave way to semiautomatic handguns capable of continuous firing.

Arming of the U.S. Police

Nineteenth-century municipal patrolmen did not at first routinely carry handguns. The infrequent but sometimes calamitous riots in large urban areas gave some impetus to carrying handguns, but the uncertainties imbedded in routine police work provided the principal motivation. Precisely how officers and their departments approached the matter of carrying handguns during the late nineteenth century remains difficult to chronicle, but we gain some sense of this from among the larger urban departments. For example, in 1857, New York State quietly provided its ”Metropolitan” police in New York City with revolvers that were to be carried in a uniform pocket. Detroit patrolmen were not provided with revolvers through the mid-1860s, but they were allowed to carry personally owned handguns. In the mid-1880s, the Boston Police Commission armed its patrolmen with Smith & Wesson .38 caliber revolvers. Near the turn of the century, Commissioner Roosevelt in New York City (NYPD) settled on a .32 caliber Colt’s Firearms revolver as the department’s approved, though not issued, handgun. By the early 1900s, the official or unofficial norm was to carry handguns, and carrying them concealed gradually gave way to wearing them in a holster worn in plain view over their uniforms.

Colt’s Firearms and Smith & Wesson dominated the U.S. police handgun market for roughly a century. The most popular cartridge was the Smith & Wesson .38 Special cartridge that the firm introduced in the early 1900s. Other revolver cartridges were developed during the middle of the twentieth century—such as the Smith & Wesson ”magnums” in .357 caliber in 1935, .44 caliber in 1955, and .41 caliber in 1963—but were not widely adopted by U.S. police even though they offered far more power than available in a .38 S&W Special. This was due to practical drawbacks; the revolvers designed for these cartridges usually were more expensive as well as larger and heavier, ammunition was more expensive, and they produced far heavier recoil, louder muzzle blast, and brighter flash in the barrel lengths favored by police.

Semiautomatic pistols were introduced to the civilian market around the turn of the century, and the U.S. Army adopted Colt’s Model of 1911 in .45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP) in the early 1900s. U.S. police remained faithful to various double-action, swing-out cylinder models by Colt’s Firearms and Smith & Wesson chambered in .38 Special through the mid-1980s. Among the earliest departments to make the change were the El Monte, California, Police Department, which adopted the Colt 1911 pistol in .45 ACP in 1966, and the Illinois State Police, which adopted Smith & Wesson’s Model 39 double-action semiautomatic pistol in 1967. Revolvers gave up noticeable ground to semiautomatic pistols in the mid-1980s and today essentially have been replaced. Now it is rare to see anything other than a semiautomatic pistol in a police officer’s holster. This also has had the effect of ushering in manufacturers that were relatively new to the U.S. police market, such as Beretta, Glock, and SigArms.

The Beretta and SigArms pistols usually are of the double-action variety in that the first shot is fired by way of a comparatively heavy, long pull on the trigger that both cocks and then releases the hammer. This is somewhat like the double-action revolver’s trigger-cocking and helps explain this design’s appeal. Subsequent shots with the double-action semiautomatic pistol, however, are fired using the second action that involves a shorter, lighter press on the trigger. This is because the hammer remains cocked after each shot. Some models are available in ”double-action only,” dispensing with the part of the mechanism that enables the shorter, lighter trigger press. The other major style of firing mechanism is the single-action venerable Colt Model of 1911 and the more recent Glock that features only one mechanism and thus a single manner for activating the firing mechanism.

Three pistol cartridges currently are popular among U.S. police. Two of these are the long-standing 9mm Parabellum and the .45 ACP, both of which trace their roots to the early 1900s, and the third is the .40 Smith & Wesson introduced in the 1990s. Glock added its .45 Glock Automatic Pistol (GAP) cartridge in 2004, which is a ballistic twin to the .45 ACP. The .45 GAP’s shorter overall length, however, permits its use in Glock’s already established line of smaller framed pistols designed for the 9mm and .40 S&W cartridges. This can be advantageous to officers with smaller hands because of the reduced circumference of the frame.

Proficiency Training

Across the first half-century of U.S. policing (1840s-1890s), there essentially was no handgun instruction, and during the second half-century (1900s-1940s), it remained the exception to the rule. Handgun safety and proficiency instruction first appeared in New York City in 1895 when its police commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt, introduced semiannual bull’s-eye target shooting through the School of Pistol Practice that he established. Although the approximately twenty shots fired by each patrolman seems very unlikely to have had much practical effect—contemporary entry-level training consumes two to three thousand cartridges per officer—this enlightened step nudged police practices toward meaningfully improving both officer and public safety.

In the 1920s, the National Rifle Association (NRA) (est. 1871) championed the introduction and improvement of handgun proficiency among the police from the editorial page to its national matches. NRA developed some practical shooting contests better suited to its practical-minded police contestants than the 25-and 50-yard bull’s-eye target matches. These police matches featured such elements as humanoid silhouette instead of bull’s-eye targets; simulated urban settings where targets appeared and disappeared from windows, doors, and corners or other concealed positions; and moving targets. NRA offered instructor development courses for police firearms instructors through it Small Arms Firing School, and it encouraged local affiliates to provide firing range access, instruction, and other assistance to state and local police.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was in its ascendancy as a law enforcement agency.

When its special agents were authorized by Congress in 1934 to be routinely armed, the FBI first looked to conventional military handgun training but then, around 1940, developed its well-known Practical Pistol Course (PPC), which became the basis for innumerable variants used widely by state and local police well into the 1980s. The generic elements of the PPC include a hu-manoid target; at least one close target distance of seven yards in better keeping with violent encounters; and greater emphasis upon gun handling such as drawing the handgun from its holster and reloading under time pressure.

Beginning in the 1980s, police slowly began to move toward more realistic firearms and deadly force training that reflects substantial change in the types and extents of marksmanship and gun handling skills, emphasis on tactics and judgment, and more comprehensive curriculum design and sophisticated instructional methods. Judgment and decision making are far more common today through live-fire tactics training, role-playing scenarios, and computer simulation exercises. Most recently, integrated training—for example, combining in one extended scenario such things as car stop procedures, approaching suspects, communication skills, applying one’s knowledge of the law, cues that might warn of pending assault, and physical and weapon-based use of force to include firearms-has been advanced as a means for achieving more realism.

These approaches seem far more likely to enhance police potential for dealing with dangerous encounters than that previously offered by the static and seemingly irrelevant nature of bull’s-eye target shooting or the rote nature of PPC courses that together formed the foundation for police firearms training during the twentieth century.