Le Blanc, Antoine (b. Mar. 20, 1802; d. Sept. 6, 1833). Murderer. On September 6, 1833, Antoine Le Blanc, a French immigrant, was executed on a gallows in Morristown. He had been convicted of brutally murdering three people on a farm where he had been employed as a laborer. An estimated crowd of ten thousand people gathered on the Morristown Green to watch the hanging. After the execution Le Blanc’s corpse was given to a group of physicians who conducted experiments by passing electric currents through the body. Subsequently, his skin was removed and sent to a local tannery, where it was made into items such as wallets, pouches, and book covers, described in a contemporary newspaper account as "charming little keepsakes.” It has been argued that this unusual treatment of the corpse was due to the hatred felt in the community for a murderer who was a Catholic and a foreigner.

Lee, Charles (b. Feb. 6,1732; d. Oct. 2,1782). Soldier. Born to a prominent English family, Charles Lee rose to the rank of colonel in the British Army. He was retired on half-pay after the Seven Years’ War in 1763. A man of strong liberal sentiments, he settled in America in 1773 with the purpose of helping the colonists. When war erupted he lobbied the Continental Congress to be appointed one of the commanders of the newly created American army, and because of his military experience was named a major general. Within a short period of time he became second in command to Gen. George Washington.

Lee performed well on campaigns in Massachusetts and South Carolina, but in December 1776 he was captured at an inn at Basking Ridge by a detachment of British cavalry, and held prisoner until his exchange in the spring of 1778. He rejoined the Continental Army at a crucial moment in the war: British commander Sir Henry Clinton had evacuated Philadelphia and was marching across New Jersey toward New York with his army of 10,000 British and Hessian soldiers.

B. Rushbrooke, Caricature Portrait of Lee, with Small Dog, eighteenth century. Engraving by A. H. Ritchie, 1918, 5 x 7 in.

Washington gave Lee the command of an advance force of 4,240 Continentals and 1,200 Jersey militia, which was to catch up to Clinton. Washington, with the remaining 7,500 Continentals, followed behind. On the morning of June 28,1778, Lee clashed with the enemy near Monmouth Court House. When Washington arrived at Monmouth a few hours later, he saw soldiers from Lee’s command streaming to the rear in apparent disorder. In one of the most dramatic incidents of the war, Washington angrily confronted Lee in the midst of the battle and berated him for his retreat. After an angry exchange of letters following the battle, Lee was court-martialed for disobeying his orders to attack, for conducting an "unnecessary, disorderly, and shameful” retreat, and for disrespect to his commander. Lee was found guilty and cashiered from the army. After a futile effort to have Congress overturn the verdict, he died in disgrace in Philadelphia.

Historians have been sharply divided over the character and accomplishments of Lee. His partisans say that he was a talented officer who, outnumbered by the enemy at Monmouth, was performing a skillful strategic withdrawal to a better position when he was interrupted by Washington. His enemies say that Lee was an arrogant, incompetent, and cowardly officer, who was jealous of Washington and sought to replace him as commander-in-chief. His severest critics charge that Lee was a traitor, secretly allied with the British.

The weight of the evidence is that Lee was no traitor and no coward—although neither was he a military genius. His action at Monmouth was a reasonable, if somewhat timid, response to a difficult battlefield situation.

Lee, Jarena (b. Feb. II, 1783; d. date unknown). Preacher. Born to free African American parents in Cape May, Jarena Lee experienced deep spiritual struggles that caused her to read the Bible and visit churches of various Christian denominations. Lee’s conversion experience took place during a period of early nineteenth-century American revivalism, when thousands were converted in meetings marked by intense emotion, often accompanied by visions, dreams, and temporary debility or illness. In the Methodist tradition that Lee joined, both men and women spoke in church, despite traditional injunctions against women speaking during public worship.

Jarena Lee, 1844.

Lehigh and Hudson River Railroad. This railroad crossed northwestern New Jersey from Easton, Pennsylvania, to Maybrook, New York, serving Phillipsburg, Belvidere, Andover, Port Morris, Sparta, and Franklin. It was what was called a bridge railroad, meaning that its purpose was to connect other railroads, in this case the Pennsylvania, Reading, Lehigh Valley, and Lackawanna in the south to the New Haven in the north. From Maybrook, trains rolled across the Hudson River on the New Haven’s Poughkeepsie Bridge Route into southern New England.

The Lehigh and Hudson River Railroad was busy through the 1960s, running sixteen through freights each way each day. It was profitable, too, as through trains received from other railroads ran solid for the entire length without any terminal expense. Traffic dwindled as connecting lines began to merge, especially after the New Haven became part of Penn Central in 1969. Traffic was down to four trains or fewer each day by 1976, when it became part of Conrail and much of it was abandoned.

Lehigh Valley Railroad. Originating in Pennsylvania as the coal-hauling Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill, and Susquehanna, the company was acquired by an industrialist, Asa Packer, who then created the Lehigh Valley Railroad in i855. Crossing New Jersey in i875 and extended to Buffalo in 1892, the company had i,i50 miles of track. The Pennsylvania Railroad operated LV’s passenger trains from Newark into Jersey City and later into New York City. The Black Diamond, the John Wilkes, and the Maple Leaf were its popular trains. The railroad became freight-only in 1961 and was absorbed into Conrail in 1976. Its route from Newark to Phillipsburg continues as a busy freight corridor for Conrail successor, Norfolk Southern Corporation.

The Lehigh and New England used several 2-8-0 locomotives of this camelback design.

Lehman Architectural Group. After graduating from the Cornell University School of Architecture, William E. Lehman established his own architectural firm, William E. Lehman, Architect, in his native city of Newark in 1896. In 1912 Lehman’s brother David J. Lehman, who studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, joined the firm. William E. Lehman’s son, William E. Lehman, Jr., and his nephews, John E. and Thomas C. Lehman, have carried on the business. The Lehman family has been active in real estate development in the Newark area, establishing the United States Realty and Investment Company in 1927. In its early years, the Lehman firm concentrated almost exclusively on private homes, apartment buildings, and theaters. In the i920s, however, Lehman turned toward commercial and industrial structures, such as the Goerke Department Store, the United States Trust Company Building, and the Progress Club. By 1979, Lehman architects had designed over five thousand buildings. In 2000 the firm, having been known as Lehman Architectural Partnership since i977, was renamed the Lehman Architectural Group.

Lehigh and New England Railroad. The Lehigh and New England Railroad crossed northwestern New Jersey on its way from the coalfields around Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, to Maybrook, New York, and a junction with the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad. Its purpose was to bring coal into southern New England. In New Jersey it served Columbia, Augusta, Sussex, and Wantage.

Lehrman, Daniel S. (b. June i, 1919; d. Aug. 27,1972). Psychobiologist. After graduating from the City College of New York, Daniel S. Lehrman received a doctoral degree from New York University in i954. He was founder and director of the Institute of Animal Behavior, Rutgers University-Newark. His pioneering studies of ring dove reproductive behavior established the field of behavioral neuroen-docrinology. He was an influential theorist of behavioral development, species-typical behavior, ethology and comparative psychology, and parental behavior in birds and mammals. Lehrman was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a visiting scientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, and founder and editor of Advances in the Study of Behavior.

Lemelson, Jerome (b. July is, 1923; d. Oct. 1, 1997). Inventor and philanthropist. Jerome Lemelson was born and raised on Staten Island, the oldest of three sons. He demonstrated an aptitude for invention while still in his youth, designing and building model airplanes and developing an illuminated tongue depressor for his physician father. After high school, his studies at New York University were interrupted by service in the Army Air Corps during World War II. He returned to graduate in 1951 with master’s degrees in aeronautical and industrial engineering. In 1954 Lemelson married Dorothy Ginsberg, an interior decorator. They settled in Metuchen and had two sons. In the attic of this home Lemelson maintained an informal laboratory where he could work on his inventions.

Lemelson initially pursued a career as an industrial engineer, but by the late 1950s was successful enough as an independent inventor that he was able to apply himself to inventing full-time. Describing his inventions as solutions for problems he saw in the world around him, Lemelson always carried around a notebook in which he recorded his ideas and had friends sign as witnesses. Most of his early inventions were toy and novelty items, but he soon branched into industrial technologies. Lemelson’s first significant commercial success was the automatic warehousing system, which was licensed by Triax Company of Cleveland in 1964.

Because of the costs involved in applying for patents, Lemelson early in his career began a lifelong practice of writing his own applications and often doing his own legal work. His first experience with patent infringement involved an idea for a cut-out face mask that could be printed on the back of a cereal box. Although his invention had been patented and then rejected by a major cereal manufacturer, the company proceeded to manufacture cereal boxes with face masks printed on them. This case was dismissed on appeal, but Lemelson eventually turned to litigation in more than twenty cases in order to protect his ideas. Some of his critics in the corporate world argued that Lemelson manipulated the system by filing patents for ideas that were not yet technologically feasible. Lemelson, in turn, criticized corporations for their "not-invented-here” attitude, a resistance to embracing ideas from independent inventors. His personal experiences and ultimate financial success turned Lemelson into a staunch advocate for the rights of the independent inventor. He also worked to strengthen federal legal protections for patents and served on the Patent and Trademark Office Advisory Committee from 1976 to 1979. In the mid-1980s the Lemelsons moved to Princeton and eventually to Nevada, where he remained until his death.

Lemelson was one of America’s most prolific inventors, holding over five hundred patents for a diverse set of inventions which included a talking thermometer, the magnetic tape drive used in Sony Walkman tape players, and brakes for in-line skates. His "machine vision device,” which made it possible for machines to read bar codes, was a huge financial success. It enabled him to establish the Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Foundation, which provided $10 million to the Smithsonian Institution to establish the Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation; it also funds the annual $500,000 Lemelson-MIT prize for outstanding inventors.

Lenape. The native people of New Jersey, whose name means "real or original people,” are also called Delaware Indians. Presumably, they descended from earlier groups, known only from archaeological traces. The Lenape spoke two dialects: Munsee in the northern part of their range, andUnami in the southern.

The population was divided into bands, each consisting of related families, which occupied traditional territories. Selected from female lineages, the chiefs were males, chosen for their wisdom, leadership, and success in hunting. They guided, rather than ruled, their people. Important decisions were announced only after consulting with village elders.

The Lenape lived primarily by foraging. Water transportation was by dugout canoe, rather than canoes fabricated from birch bark. There was an extensive network of overland trails.

Hunting, both communal and solitary, was practiced with bows and arrows. The Lenape hunted deer, bears, other mammals, and birds. In communal hunts, the animals were driven by fire to waiting hunters. The Lenape also devised animal traps. Fish, including shad and sturgeon, were speared, harpooned, netted, or captured in weirs. Shellfish were gathered both on the seacoast and from fresh waters. The Lenape also harvested nuts and berries. Later, certain groups began planting corn, beans, and squash. Surplus food was sometimes stored in subterranean pits, which later were used for refuse disposal and even for burials. The dead were often buried in flexed postures, sometimes with a few grave offerings.

The men hunted and fished, engaged in trading, and made equipment. The women tended to gardening, cooking, housekeeping, and childcare. They also prepared skins. The males wore loincloths, while females wore skirts. Both usually went about bare-breasted, but might wear sashes or headbands. In winter, cloaks of fur or turkey feathers provided warmth. Buckskin moccasins protected their feet, and leggings were sometimes worn.

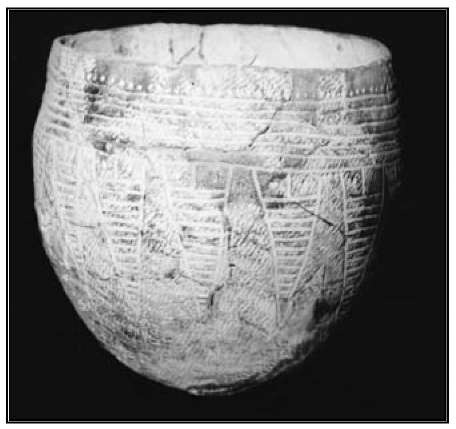

Late prehistoric ceramic vessel from southwestern New Jersey.

Houses were constructed from bent saplings and covered with bark. The largest houses sheltered several related families, the smallest, perhaps only one or two people. Sweat lodges were used for purification.

The Lenape made clay containers, cooking pots, and smoking pipes, some of which were ornately decorated. They fashioned bowls and utensils from wood and gourds. Foodstuffs were ground using mortars and pestles of wood or stone. Cordage, fabrics, and nets were fabricated from plant fibers or sinew, while wooden splints, rushes, or cornstalks were woven into baskets and mats. Woodworking tools, knives, and weapon tips were made from stone, bone, and antler. The latter materials also served for making awls, skewers, and needles.

Paint from mineral and plant pigments was used for adornment, along with feathers, porcupine quills, and beads of shell (wampum) and bone. Many people kept personal items-pipes, tobacco, and fetishes, for example—in small leather or fur pouches. Ritual masks were carved from wood or woven from plant materials.

The Lenape had a complex religion, according to which a Creator made the universe and gave spiritual life to everything in it. Another deity protected the animals of the forest. A personal spirit or totem, the Lenape believed, guided most people.

The growing population of European settlers eventually displaced most of the Lenape to midwestern states and Canada, where their descendants still reside. Between 1758 and 1802, as many as three hundred Indians occupied the Brotherton reservation at Indian Mills. A few remain in New Jersey today.

Lenape stone. The Lenape stone, an engraved slate tablet 4.5 inches long and 1.5 inches wide, was discovered by Bernard Hansell in 1872, near Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Today it is in the collections of the Mercer Museum in Doylestown. The stone’s surface is almost entirely covered by carvings. Those on the front depict an encounter between a mammoth and a group of stick-figure American Indians. On the obverse, the carvings include a turtle, a tobacco pipe, fish, teepees, and other symbols. Coming to light in the midst of great debate regarding the earliest human presence in the Delaware Valley, the stone seemed to support the coexistence of ancient Native Americans and long-extinct animals like mammoths. Most scholars of the time, including Charles Conrad Abbott, a major proponent of "paleolithic” settlement in the New World, believed it fraudulent. Today it is generally believed to be a fake, although the exact circumstances of its manufacture remain unknown.