Jersey Devil. A legendary creature of South Jersey, native to the Pine Barrens, the Jersey Devil is said to have the head of a horse, the torso of a man, the wings of a bat, the legs and hooves of a goat, and a long serpentine tail. The story, which exists in different versions, has been in oral circulation since the devil’s reputed birth in 1735. Like other legends, the story has been passed down within families—father to son or mother to daughter—generation after generation. To this day, there are active tradition-bearers who grew up with the story in family, home, and community.

According to one version, the Jersey Devil was born to Jane Leeds, who lived with her husband, Daniel, near a swamp along the Mullica River. The couple had a large family of twelve children, requiring an exhausting amount of effort and attention. When Jane Leeds learned that she was pregnant with her thirteenth child, in a moment of understandable weakness and anger, she prayed, "Lord, I hope this one is not a child. Let this one be a devil!” Unfortunately, her prayers were answered. Shortly after the creature was born, he escaped into the Pines where he has lurked and terrified the people of South Jersey ever since.

Over the years, there have been many eyewitness sightings of the Jersey Devil, some by respectable members of society. Yet there has Museum opened as a historical museum in 1901 in the city’s public library. It is best known for its collection of paintings by nineteenth-century American artist August Will, documenting the changing landscape of Jersey City. Much of the museum’s activities were curtailed during the 1950s. Through community effort it underwent revitalization in the mid-1970s, when a professional staff was hired and the work of cataloging the collection and mounting exhibitions progressed. In 1993, the city donated a building to the museum for its relocation. After renovation, the new facility opened in 2001, continuing its mission of exhibiting historical art and artifacts relating to the area and work by contemporary artists demonstrating the cultural and artistic diversity of the region.

Littoral Society, and the New Jersey State Federation of Sportsmen. JCAA also sponsorsfish-eries tournaments and tries to improve youth participation and education programs.

Tom Van Pelt, The Jersey Devil Skeleton, a representation sculpted from animal bones found in the Pine Barrens of South Jersey.

Jersey Coast Anglers Association. The Jersey Coast Anglers Association (JCAA), a nonprofit organization, was started in 1981 by more than seventy-five saltwater never been any hard evidence or scientific proof of the creature’s existence. So far, for example, there have been no reliable plaster casts of footprints or confirmed photographs. The lack of evidence does not disprove the existence of the creature, however, so philosophically it remains an open question.

What interests folklorists is the question of why the stories persist and even flourish. For some, the story undoubtedly had a child-rearing function, to protect young children from the real dangers of the Pines. A parent might say, "Be sure to get home before nightfall, or the Jersey Devil will get you!” Others in the Pines, engaged in illegal activities, such as smuggling or bootlegging, might want to frighten outsiders and discourage intruders by promoting the story of a fearsome monster.

The Jersey Devil remained an obscure regional legend until 1909, when there was a rash of sightings in South Jersey, widely reported in newspapers. Capitalizing on the sudden interest, an enterprising Philadelphia businessman staged a hoax. He charged admission to the public to view a kangaroo with green stripes and fake wings, which he called "The Jersey Devil.”

In the mid-1980s, a National Hockey League team relocated to the Meadowlands and took the name the New Jersey Devils, an interesting development because a North Jersey team was taking the name of a South Jersey legend. One result was that a creature from agricultural and rural South Jersey was suddenly catapulted into statewide attention and into the realm of popular culture. It is now possible to find Jersey Devil T-shirts, bumper stickers, postcards, posters, and even namesake cocktails.

Jersey Glass Company. Located in the Paulus Hook section of Jersey City near the Morris Canal, from 1824 to 1862, this important glassworks produced a varied range of fine and utilitarian household objects as well as druggists’ wares. George Dummer was the principal developer. Trained as a glass cutter, he was a seller of imported glass and ceramics in Albany and New York City. After setting up the factory, Dummer maintained the company sales office across the Hudson River in lower Manhattan. The operation was immediately successful and by the 1840s employed 150 workers. Its products, mostly blown and cut glass, included flute glasses, wine goblets, bowls, decanters, compotes, lampshades, pitchers, and paperweights. While the company’s products earned many awards in its lifetime, its few surviving pieces are recognized almost solely through association with Dummer family descendants. The exceptions are a number of oblong, pressed-glass salt dishes, marked "Jersey Glass Co Nr N. York.” The business existed under various names, including George Dummer and Company and P. C. Dummer and Company (Phineas Cookwas the younger brother of George). Dummer also founded the short-lived Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company on an adjacent lot. In 1867, a sugar refinery was erected on the site, removing most traces of both operations. Parts of the factory’s foundation were excavated in 1988 and 1989.

Jersey jokes. Among the fifty states, New Jersey is notorious as the object of humor. In these jokes, New Jersey is depicted as an unfashionable place pervaded by criminality, dim-wittedness, and pollution.

Jersey bashing has a long history. In 1872, the magazine Picturesque America observed that ever since New Jersey became a state, "it has been the butt of sarcasm and wit of those who live outside her borders.” Perhaps the first Jersey joke was a remark (often attributed to Benjamin Franklin, though no evidence links him to it) that New Jersey was a barrel tapped at both ends. Besides being a put-down, the remark is quite astute. New Jersey has long been dominated by New York and Philadelphia, which, like urban centers since time immemorial, regard themselves as hubs of sophistication, surrounded by an ignorant hinterland. There seems to be a human need to find places and peoples to feel superior to, and for much of the nation, unassuming, hardworking New Jersey has filled the bill.

Examples of the New Jersey joke abound. In Woody Allen’s 1973 movie Sleeper, a character explains his philosophical view that the universe is guided by an intelligent force—except in certain parts of New Jersey. In the 2001 comedy Heartbreakers, a sleazy character is asked if he can cover up a suspicious death. "I’m from New Jersey aren’t I?” he replies, as if this subject were taught in the state’s schools.

In a New York nightclub, a comic asks if anyone in the audience is from New Jersey. When hands go up, he snaps back, "What-samatta, bowling alleys closed tonight?” An Internet site presents the official New Jersey state motto as "I don’t have to show you no $#%&# motto!” A joke asks why New Jersey has more toxic waste dumps than any other state while California has more attorneys. "Because New Jersey got to choose first” is the punch line.

New Jerseyans (who, surveys indicate, have a high level of satisfaction with their state) occasionally strike back. In 1991, the New Jersey Devils hockey team journeyed to Toronto for a play-off series with the Maple Leafs.

A deodorant company ran advertisements in the city’s newspapers showing a stick of deodorant and a map of New Jersey. The tag line read, "Unfortunately, there are some smells even we can’t do anything about.” The acting governor of New Jersey issued a protest, and the CEO of the deodorant firm apologized for its "disrespectful and disparaging” advertisement.

New Jersey won that round, but it appears likely that the state will continue to be subjected to Jersey jokes. A Texas magazine, in fact, has begun a movement to designate the first week of July every year as "Be Kind to New Jersey Week,” a proposal that is itself a Jersey joke. Garden State residents weary of this sort of abuse might do well to adopt the stoic attitude of a New Jersey magazine editor, who observed with a shrug, "So New Jersey gets dissed. So what?”

Jersey Journal. The first issue of what was then called the Evening Journal was published on May 2,1867, by Major Z. K. Pangborn and Captain William B. Dunning. A partial interest in the newspaper was sold to Joseph Albert Dear, who was a former editor of the Jersey City Times. The newspaper proclaimed that it wanted to promote equal rights for all Americans, including freed slaves. The name of the newspaper was changed in 1908 to the Jersey Journal. In 1925 the offices were moved from their original location at 13 Exchange Place in Jersey City to 30 Journal Square, where they have remained. In 1945 a 50 percent share of the newspaper’s publishing company, the Evening Journal Association, was sold to S. I. Newhouse. By 1952 Newhouse owned 100 percent of the newspaper and it became part of the family’s Advance Publications newspaper group. TheJerseyJournal’s weekday circulation was forty-four thousand in 2000, but with dwindling circulation in 2001, the company offered staff buyout packages and mandated some union employee layoffs in an effort to save the newspaper from closing down.

Jersey Shore. The attractions of the Jersey Shore can be understood by arriving early on a summer day at one of its beaches. Footprints have been washed away by the night’s tides, and the white sand is fresh and cool, awaiting its new arrivals. Surfers and fishermen are among the first to come, often at sunrise, since their activities benefit from a lack of crowds. Walkers arrive next. Ambling along on the sloping sand is a challenge, but the orange ball of the sun and gray-green waves are spectacular rewards. When the lifeguards take up their posts, the pace quickens. Families arrive; children enter the water. Slowly the beach is covered by paraphernalia: blankets, towels, umbrellas, boogy boards, tubes, water wings, toys, folding chairs, coolers, hats, reading material. A beach volleyball game is organized; a prodigious quantity of sunblock is applied. The heat of the sun and the energy of the people reach their apex in the early afternoon. Then, as the sun loses its intensity, bathers begin to leave. Soon the lifeguards go off duty. At dusk the fishermen, surfers, and walkers return and, at night, teenagers seek summer romance on the dark beach and under the boardwalk.

Many citizens of New Jersey, this highly industrialized and most densely populated state, gleefully load up their cars each summer and head "down the Shore” to repeat a version of this ritual day-at-the-beach (the Shore has such prominence in the New Jersey imagination that Shore is conventionally capitalized). While Shore denizens come from many states and even foreign countries to vacation at one of the forty-some Shore towns, New Jerseyans are its principal users, since most can reach the Shore by car in little more than an hour. Nineteenth-century poet Walt Whitman believed it was the "sea-side region that gives stamp to Jersey,” and he was right. Some New Jerseyans even buy a special Shore license plate to affirm this essential connection.

Visitors have considerable choice about where to stop on New Jersey’s long coastline. Along its 127-mile length, the Shore has seven distinct areas: Sandy Hook, the Northern Shore, Barnegat Island (until 1925 a peninsula), Long Beach Island (LBI to regulars), Atlantic City, the Southern Shore, and Cape May. Some authorities consider the easternmost portion of the Pine Barrens, around the estuary of the Mullica River, an eighth area, and a number of inland towns, with no ocean or even bay frontage, also fancy themselves part of the Shore. Thus, the limits of the Jersey Shore are somewhat open to interpretation.

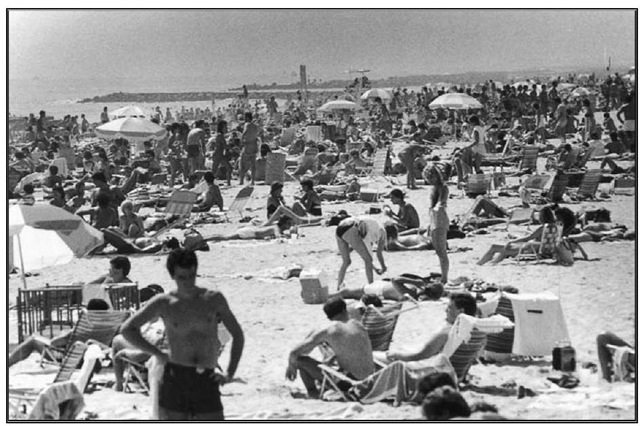

Crowds enjoy the beach in Belmar on Labor Day weekend, 1983.

Each area, town, and city at the Shore has a unique character, and vacationers often return to the same place each summer, generation after generation. Philadelphians, not surprisingly, favor the Southern Shore and Cape May. And religious and ethnic groups long ago settled or populated favorite areas, giving such towns as Ocean Grove, founded by Methodists, and Spring Lake, the so-called Irish Riviera, a particular cultural flavor.

For those who come to the Shore principally for sun and ocean, the summer months are best. Beginning with Memorial Day, the pace accelerates rapidly. High school prom-goers, for whom an overnight at the Jersey Shore is a rite of passage, are early summer visitors. Then come homeowners to check for damage and to sweep out the sand that enters everywhere. They are quickly followed by day visitors, who must contend with each town’s rules with regard to parking, beach access, and purchase of beach passes. Then, there are the seasonal renters, who stay in everything from motels and the barracklike bungalows of Normandy Beach and Lavallette to elegant homes they contracted for in the dead of winter.

Some Shore residents distastefully term the day-trippers "Shoobies” or "Bennies.”Every vacation community has its own language for the summer folk it both needs and dreads. Shoobies is an antique term for day visitors who brought their lunch in shoeboxes. Bennies is a mostly southern Shore term of disputed origin for visitors who usually change into their bathing suits out of the trunk of their car, somehow hosing themselves off after a day at the beach.

Middle-class shoregoers, whether day, seasonal, or residents, give the Jersey Shore its character. The Shore has its mansions, such as those in Mantoloking and Deal, and it has poverty, such as the depressed areas of Atlantic City behind the casinos and much of Asbury Park. But it is distinct from more upscale East Coast resorts like the Hamptons and Cape Cod by virtue of its predominantly middle-class character. Alice Logan, an actress and writer whovisited Long Branch in i875,ob-served that the town "is perhaps best in accord with the spirit of American institutions than any other of our watering places.” Sir Alfred Low, an English writer in the early twentieth century, called Atlantic City "the Middle-Class Playground,” and the same can be said of most of the Shore today.

The Jersey Shore has also been derided for this very middle-class aspect and for being overdeveloped and tawdry. Similar labels have long been applied to New Jersey as a whole, especially by the New York media, and the Shore’s image parallels the state’s. Not surprisingly, the music of the man most responsible for the renaissance of New Jersey’s image was inspired by his Jersey Shore heritage.

Bruce Springsteen came out of the Shore rock ‘n’ roll club culture of the 1970s, a culture that still produces fine musicians. While many saw the overdeveloped boardwalks or the abandoned buildings of Asbury Park as the worst of the Shore, Springsteen, born in Long Branch, saw these aspects as key to its allure. Such songs as "Fourth of July, Asbury Park (Sandy),” "Tunnel of Love,” and the Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. album suggest that the Shore has a distinct and vital culture of its own.

This culture has a long history. American Indians were the first to come to the Jersey Shore, but were pushed off the land by European settlers who established whaling, clamming, and salt mining businesses. The Jersey Shore as resort began in the 1830s, when the first hotels were built. Rail links made it possible for large numbers of people to travel to the Shore. Earlier, the difficult journey in carriages or boats made the trip too uncomfortable for all but the most adventurous. Soon places such as Long Branch set up "bathing huts” under the bluffs made famous in Winslow Homer’s 1869 painting Long Branch, New Jersey. In these huts, vacationers could rent "bathing dresses” and emerge properly covered. Increasingly, many wealthy and famous guests came to the Shore, including Presidents Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James Garfield (in a failed attempt to recover from an assassin’s bullet), Chester Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, and Woodrow Wilson. The Shore became generally available to the middle class only with the building of federal and state roads such as the Garden State Parkway.

The Jersey Shore as past and present-day visitors and residents know it was not always in its present location. Geologists believe that, in a late glacial age, it was some ninety miles inland, and this explains the immense sandi-ness of the Pine Barrens, which occupy much of the southeast quadrant of the state. Today, except for the section from Manasquan to just above Long Branch in the north, Cape May in the south, and numerous tidal inlets, the Shore’s form is that of a bow-shaped, almost complete barrier island coast. This formation has created two Shore environments and cultures, bay side and ocean side. New Jersey Bayshore areas, such as Barnegat Bay, Great Bay, and Sandy Hook Bay, are especially enjoyed by boaters, water skiers, and wind surfers and harbor the New Jersey section of the Intracoastal Waterway, a north/south boat route extending all the way to Florida.

The Shore is under constant assault from the elements, even on a sunny day, and beach accretion and erosion constantly revise the Shore’s map. The spectacular hurricanes that occasionally hit sometimes shift the real estate map of the Shore as well, destroying countless oceanside homes. The town of Loveladies on Long Beach Island, for example, contains homes built almost exclusively after 1962, the year a storm wiped out much of the town. Navigational technology has decreased the number of shipwrecks, but the Jersey coast is full of dangerous shoals and sandbars, and experienced fishermen, pleasure boaters, and swimmers have too often underestimated its challenges.

Many also underestimate the fragile nature of the Shore, and the ease with which its amenities can be spoiled, not just by acts of God but by acts of man. Visiting Wildwood in 1892, ornithologist Charles Conrad Abbott declared, "I am at last in a bit of Jersey’s primeval forest”; but those "wild” woods were soon replaced by homes. Today, numerous state parks and nature preserves at the Shore protect its trees, waters, beach grasses, dunes, and birds from pollution, depletion, or extinction. The bays’ salt marshes harbor countless bird species such as egrets and herons. Like their human counterparts, some birds, such as the red knot, use the Shore as a mere stopover, while others nest year round. Sandy Hook has the magical Holly Forest, a sanctuary for the curious, ocean-stunted holly trees and for migrating birds who take advantage of its location on the Atlantic Flyway. In Avalon, the World Wildlife Fund owns a thousand acres of wetlands; and the Trust for Public Land has designated thousands of acres of the Shore for protection.

Despite these efforts, many Shore bird, bog turtle, and horseshoe crab populations are dwindling. The Jersey Shore is balancing with difficulty a push for development with a pull for preservation, as the importance of a clean, thriving Shore to the state’s sense of itself becomes clearer. The medical wastes that in the late 1980s forced the closing of some Jersey beaches created publicity that fostered change. But the threats to the environmental health of the Shore are many and complex. So, while there is a Shore Preservation Fund which allocates millions for sand replenishment along the coast, the systematic destruction of sand dunes to build the original boardwalks was an act of environmental folly that wounded the Shore grievously.

The future of the Shore is important not only for recreation but for the economic well-being of New Jersey. Atlantic City’s casinos and the Shore generally are the first and second most profitable state tourist destinations. Other beach towns besides Atlantic City that capitalize on their boardwalks are Point Pleasant Beach, Seaside Heights, Ocean City, and Wildwood. These boardwalks and their amusements attract enormous crowds of people. For lovers of kitsch, the boardwalks are replete with folk sculptures and paintings, fantastic in their gaudiness. Seaside Heights may be the acme of what people most like and dislike about the Jersey Shore. Yet for many families, these are the principal towns they head for each summer for a two-week vacation, saturating themselves with beach time by day and boardwalk time and junk food by night.

The largest number of Jersey Shore visitors head to Atlantic City. Originally tourists traveled to Atlantic City for the water and the Boardwalk promenade, the first at the Shore. However, after giving the world saltwater taffy, rolling Boardwalk chairs, the Miss America Pageant, Lucy, the sixty-five-foot-high elephant museum and national landmark (in nearby Margate), as well as the street names for the popular board game Monopoly, Atlantic City became a depressed resort. Since 1978, when legalized gambling was initiated in Atlantic City after a statewide referendum, the city’s main attraction has been its casinos and hotels with twenty-four-hour-a-day entertainment. In his 1980 movie Atlantic City, the French director Louis Malle captured the moment when the then-rundown city evolved from backwater to glitzy casino boomtown. Revenues from gambling in Atlantic City now exceed those of Las Vegas. Although it still has many extremely poor neighborhoods, Atlantic City’s hotels, convention centers, and casinos are booming. Buses whose only stop is "Atlantic City” regularly take passengers with rolls of quarters for a day of gambling at casinos such as the Trump Plaza or the Taj Mahal, the world’s largest casino complex. Reporting on another Shore town in 1892, the writer Stephen Crane noted that on its boardwalk "there are a number of contrivances to tumble-bumble the soul and gain possession of nickels.” Updated for inflation, that’s a good description of Atlantic City’s casinos today. Atlantic City hosted over 34 million visitors in 1998, making it the nation’s premier tourist destination.

There are, however, many New Jerseyans who require more than a day trip to Atlantic City or a two-week vacation elsewhere, and who desire the sights and sounds of the ocean year round. Residence in the Shore areas of Monmouth, Ocean, Atlantic, and Cape May counties allows them to enjoy the quiet beauty of the Shore’s off-season. This beauty is especially evident in September, when the crowds are gone and the ocean is still warm enough for swimming. Many who work in the Shore’s marine industries have always been residents. But beginning in the 1960s, the populations of the Shore communities grew rapidly, with much of it from senior citizen communities. Younger people have also settled full time on the Shore. Condominiums are going up rapidly everywhere.

Other Shore communities have, instead, discovered the virtues of architectural preservation. Cape May, like the northern Shore town of Ocean Grove, was an early convert to its benefits. Its large stock of Victorian housing and hotels was renovated in the 1960s and 1970s, making it, as it was early in the Shore’s life, a renowned tourist destination for shoregoers who enjoy architecture and antique shops. Like Atlantic City, Cape May illustrates that many come to the Shore for attractions other than sand and water.

Yet, for most, the beaches are the Shore. Whether boating, swimming, fishing, surfing, reading a book, or just watching a child build a sandcastle at water’s edge, the beaches unite disparate towns and Shore lovers in the elemental enjoyment of beach culture. And each year millions get in their cars, turn on some tunes, and head to pristine and undeveloped Island Beach State Park, to Manasquan, or to another of New Jersey’s Shore communities. There they can indulge their fascination with the simple power of water and the great mystery of waves endlessly beating on a long, sandy coast.

![tmp5-38_thumb[1] tmp5-38_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/tmp538_thumb1_thumb.jpg)