Dinosaurs. New Jersey played an important role in the early discovery and study of dinosaurs, the dominant land animals of the Mesozoic Era, in North America. In the nineteenth century, numerous discoveries of dinosaur partial skeletons, isolated bones, and teeth were made in the marl pits of southern New Jersey. In addition to Hadrosaurus, the official state dinosaur, early paleontologists described Dryptosaurus, a larger meat eater, and Coelurus, a smaller, hollow-boned dinosaur, from the Late Cretaceous deposits of the Garden State. Both E. D. Cope and O. C. Marsh were active in the state at this time, and their famous "Bone War” feud, which led to the discovery of many new dinosaur types, started in the New Jersey marl pits.

Besides Late Cretaceous dinosaurs, the red rocks of New Jersey’s Newark Basin contain footprints of many smaller early dinosaurs from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic parts of the Mesozoic era. These footprints and trackways record the increase in variety and in size that led to the success of the dinosaurs as a group. Most of these tracks were made by small to medium-sized carnivorous dinosaurs.

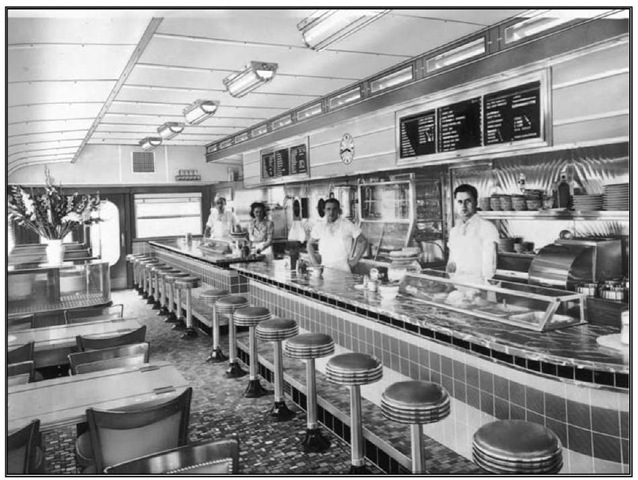

Interior of Joe’s Diner, Egg Harbor, c. 1940.

Disbrow, Levi (fl. i82os-i83os). Engineer. Levi Disbrow, an ingenious mechanic, lived at various times in Piscataway, Franklin, and New Brunswick. He bored the first successful artesian well in the United States in May 1824, in New Brunswick. It was 175 feet deep and supplied pure water for J. H. Bostwick’s distillery. Over the next several years he and his agents were at work at numerous sites from the Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, to Boston. His unprecedented exploits were admiringly reported in many newspapers and magazines.

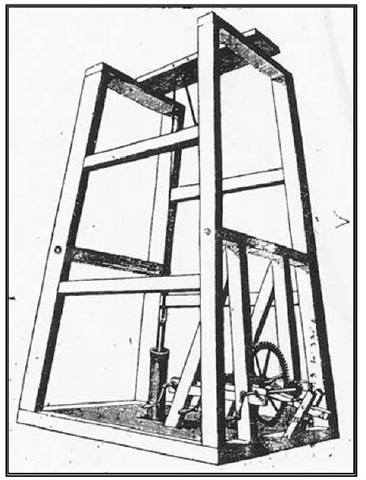

Disbrow obtained patents for his rock-boring machinery in 1825, 1830, and 1832. In 1828 he was involved in a fanciful scheme, financed by the Raritan Coal Company, to locate and mine coal beneath the Raritan River. No coal was discovered.

After 1828 his base of operations was in New York City. His well for the Manhattan Company was bored through granite to a depth of 448 feet. Between 1832 and 1834, Disbrow and a partner, J. L. Sullivan, sought to persuade the Common Council to rely on bored wells to meet future needs. Instead, the council wisely decided to bring water to the city from the Croton River. There is no record of Disbrow after 1836, when his son John took over his business.

Levi Disbrow’s earth-boring machine.

Discrimination. Because discrimination—biased acts against individuals—fre-quently results in injury to those targeted, the U.S. Constitution bars state governments from engaging in certain kinds of discrimination, as does, since 1947, the New Jersey state constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court has determined that the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment imposes an antidiscrimination mandate on the states. Enacted during Reconstruction, when the rights of African Americans were the central issue, the Fourteenth Amendment assumed wider importance during World War II when Californians of Japanese descent were singled out and subjected to curfews, confiscation of property, and even incarceration under the justification of national security. In later years, the Court has determined that in themselves, racial classifications are presumptively odious and therefore require close judicial scrutiny.

Judicial review under the equal protection clause is limited to discrimination involving the state or its agents; it does not apply to private discrimination. The Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, has been held to apply to private discrimination, but only that kind deemed either a badge or incident of slavery. As a result, it is judicial interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment that sets the important standard. States, though, are not limited in their antidiscrimination efforts by the federal standard; they just are not permitted to fall below it.

Some states, including New Jersey, have set higher standards. New Jersey passed its first law against racial discrimination in 1884, just as the federal court limited the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment. The statute, however, was rarely used. In 1945 the Law against Discrimination (LAD) was enacted, providing an administrative remedy as well as judicial review; its focus was employment. It barred "discrimination against any of its inhabitants because of race, creed, color, national origin or ancestry.” In 1947 the new state constitution added to the state bill of rights a clause prohibiting discrimination. Pushed by Oliver Randolph, the only African American at the constitutional convention, this clause prohibited discrimination in schools or in the militia (National Guard). New Jersey was the first state to have such a constitutional provision.

Current notions of proscribed discrimination in New Jersey extend far beyond the categories covered in the 1945 LAD. By 1949 public accommodations, as well as schools and the militia, were the focus. It was housing in 1951, aging and employment in 1962, public contracts in 1966, and housing again in 1967. Gov. James Florio issued an executive order in 1991 that expanded the groups entitled to the state’s protection to include sexual orientation. In 1992 Gov. Christine Todd Whitman signed into law, amending the LAD, a provision prohibiting discrimination based upon "race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, age, marital status, familial status, affectional or sexual orientation, atypical hereditary, cellular or blood trait, genetic information, liability for service in the Armed Forces of the United States, or disability.” These categories place New Jersey in the vanguard—only eleven states have included gender as a basis of entitlement to the state’s protection.

Division against Discrimination.The Division against Discrimination was created in 1945, with the enactment of the Law against Discrimination (LAD), as an arm of the New Jersey Department of Education. The new division was a direct response to an ineffective 1884 statute barring racial discrimination; the 1884 statute had seen limited use because of an array of procedural problems and the inability of aggrieved parties to finance costly litigation. The new division provided an administrative remedy for allegations of discrimination in employment, subject to judicial review by the state’s highest court, and declared the right to employment to be a civil right. It barred "discrimination against any of its inhabitants because of race, creed, color, national origin or ancestry.” Fifteen years later the Division against Discrimination was removed from the Department of Education and placed in the Department of Law and Public Safety as the Division of Civil Rights—its present location— with greater emphasis on enforcement.

Division on Women. A permanent agency in the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, the Division on Women serves as the coordinator of state government programs and services for women. With the guidance of the New Jersey Advisory Commission on the Status of Women, the division administers programs, provides grants and technical assistance, supports information hot lines, and promotes legislation that advances women’s socioeconomic status and legal rights.

The division was established by statute under the Division on Women Act of 1974; it replaced the Office of Women in the Division of Human Resources, Department of Community Affairs. Patricia Q. Sheehan, then commissioner of the Department of Community Affairs, was appointed acting director. The division’s first director was Clara Allen.

Dix, Dorothea Lynde (b. Apr. 4,1802; d. July 18, 1887). Reformer, mental health advocate, Union Army nurse. Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Dorothea Dix, at age fourteen, opened a school for twenty children. Dix furthered her own education with long hours of extensive reading, and then opened schools in her grandmother’s mansion in Boston, one for wealthy girls and another for poor children. In six years she published seven books, but the intense pace of her work caused her health to fail, and in 1836, she went to England to convalesce.

Returning to the United States, Dix toured housing for the mentally ill in Massachusetts, and in 1843, her "Memorial to the Legislature of Massachusetts,” which advocated building units for the mentally ill at state hospitals, was presented to the all-male state legislature by Dr. Samuel Howe, husband of Julia Ward Howe. Dix’s study was called "the first piece of social research ever conducted in America,” and the legislation passed on February 25, 1843, hailed as the most sensational passed in Massachusetts since the Revolutionary War.

In New Jersey, Dix followed the same course. She toured jails and county alms-houses that housed the state’s more than six hundred mentally ill, and then met with small groups of legislators, wrote newspaper articles, and encouraged writing campaigns to persuade others. On March 25, 1845, her "Memorial” became law. Dix advised builders about the site and plans for a new hospital in Ewing Township, and in May 1848, the New Jersey Lunatic Asylum (Dix’s "first-born child”) was opened.

Dix visited every state east of the Rocky Mountains, crusading for humane treatment of the mentally ill. Then, between 1848 to 1854, she lobbied in the U.S. Congress for passage of a bill to set aside federal land funds for use by the insane poor. Congress passed the measure but President Franklin Pierce vetoed it, destroying hopes for a nationwide system of humane health care institutions.

Dorothea Lynde Dix.

When the Civil War broke out, Dix’s organizational skills earned her the position of superintendent of women nurses in the Union Army, but after the war, she returned to her campaigns for the mentally ill. A charismatic reformer, Dix was in frail health most of her life, and feeling personally inadequate, she avoided public appearances and formal social gatherings, even declining White House invitations.

Before most people, Dix believed that industrialized societies created stress, and that these societies must assume care of their mentally ill in humane ways. She was responsible for founding or enlarging thirty-two mental institutions in the United States and abroad.

Dixon, Franklin. Franklin Dixon is a pseudonym created by juvenile fiction mogul Edward L. Stratemeyer that was used by more than two dozen ghostwriters. Dixon is the listed author of the Ted Scott Flying Stories and the vastly popular Hardy Boys series. Part mystery, part adventure, the Hardy Boys series recount the exploits of Joe and Frank Hardy, proteges of their world-famous detective father. Although sales of Hardy Boys books have been in decline since World War II, they remain the longest running, best-selling series of books for boys.

Edward L. Stratemeyer was a prolific juvenile fiction writer and president of the Stratemeyer Literary Syndicate, which produced more than one hundred series, including the Bobbsey Twins, Tom Swift, and Nancy Drew as well as the Hardy Boys. The syndicate office was located in East Orange and was later transferred to Maplewood.

In 1926, Stratemeyer placed an advertisement in the trade journal Editor and Publisher: "Experienced fiction writer wanted to work from publisher’s outlines.” The notice, nestled among others calling for copyeditors, piqued the curiosity of the journalist and aspiring fiction writer Leslie McFarlane (1902-1977), who was subsequently hired to become the original Franklin Dixon. McFarlane penned the first eleven and five later volumes of the 140-book series. The pen name Franklin Dixon was the legal property of the syndicate, and great measures were taken to present him as a bona fide author to the reading public. Authors for the syndicate signed contracts promising to conceal their true identities. According to his memoirs, The Ghost of the Hardy Boys (1976), McFarlane kept his identity as Franklin Dixon hidden from even his own children until they were grown. Although McFar-lane and Stratemeyer were close collaborators for the first four years of the series (until Stratemeyer’s death), the two never met nor spoke.

At the time of Stratemeyer’s death, the syndicate was producing 80 percent of all juvenile literature in the United States. Control of the syndicate passed to his two daughters, Harriet Adams and Edna Camilla Squier, who continued to oversee the output of "Franklin Dixon.” Adams, who wrote several of the Hardy Boys herself, remained in control of the syndicate until her death in 1982. In 1984, the syndicate was sold to Simon and Schuster.

Dixon, Joseph (b. Jan. 18, 1799; d. June 15, 1869). Inventor and manufacturer. Joseph Dixon was born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, the son of Joseph and Elizabeth Reed Dixon, and remained a resident of his native state for the next forty-eightyears. He married Hannah Martin, also of Marble-head, in 1822. He had little formal education, but early on demonstrated an aptitude for mechanical pursuits. In his teens, Dixon invented a machine for cutting files; soon after, he became a printer. Because he did not have the wherewithal to buy metal type, Dixon made his type out of wood and in the process developed skills as a woodcarver and also learned wood engraving and lithography. Still, he wanted to work with metal type. Consequently, he perfected a way to cast his own. This, in turn, led him to experiment with graphite as a substance for receptacles into which he could melt his type.

As he worked with graphite, Dixon recognized other of its properties and soon produced goods using it that became widely popular, including stove polish, lubricants, and lead pencils. In 1827, he built a factory in Salem, Massachusetts, and began to manufacture these materials.

In 1847, Dixon moved his manufacturing plant to Jersey City to be closer to his customers. He was subsequently granted several patents in a variety of fields. Two of the earliest, awarded in March and April of 1850, covered the use of graphite crucibles in the making of pottery and steel. Dixon had earlier used the principles explained in this patent to produce iron and steel during the Mexican War. In 1858, the patent office recognized his application for the "improvement in manufacturing steel.” As well, Dixon perfected a process for using graphite to grind lenses, invented a way to print calico in fast colors, discovered a method for tunneling under water, and produced a galvanic battery. Dixon acquired mining property and mills in Ticon-deroga, New York, to support his manufacturing activities. He befriended such luminaries as Robert Fulton, Samuel F. B. Morse, and Alexander Graham Bell.

During the 1860s, most people still used quill pens and ink; however, consumer demands for a dry writing instrument were growing. This led to the mass production of pencils, and in 1866, Dixon obtained a patent for a wood-planing machine that was specifically designed to give shape to wooden pencils. In 1867, in failing health, Dixon thought it prudent to incorporate all of his business interests; as a result, he formed the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company. When Dixon died two years later, his company was the largest maker of graphite products in the world.

Doane, George Washington (b. May 27,1799; d. Apr. 27,1859). Bishop, educator, and poet. The only son of Jonathan Doane, builder of New Jersey’s first State House, and Mary Higgins, George Washington Doane was born in Trenton. After his graduation from Union College in 1818, Doane read law but soon turned to the study of the ministry, entering General Theological Seminary in 1820. He was ordained a deacon of the Episcopal Church in 1821 and priest two years later, serving as an assistant at Trinity Church, New York City. From 1825 to 1828, he taught rhetoric and belles-lettres at Trinity College and became involved as an editor for church publications. He was called to Boston’s Trinity Church in 1828 and in 1829 married Eliza Greene Callahan Perkins, a wealthy widow.

The Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey elected Doane its second bishop in 1832. As there was no independent support for the bishop, Doane accepted the rectorship of Saint Mary’s Church in Burlington (founded 1703). His episcopate was marked by great expansion with over twenty new parishes established. Doane supported the education of girls, founding Saint Mary’s Hall (1837), and established Burlington College for men. A friend of William Wordsworth, he was interested in poetry and hymnody, writing "Thou Art the Way” and "Fling Out the Banner,” among other hymns. His residence by John Notman (1846; demolished 1965) was the first Italianate structure in the United States and New Saint Mary’s Church, built 1846-1854 by Richard Upjohn, was the first Gothic Revival structure. A friend of the Oxford movement, Doane was considered a leader of the High Church party in the United States.

In 1849, he was charged by his critics for misuse of Church funds. Doane defended himself successfully in an ecclesiastical tribunal but the trial took a toll on his health and fortune. He died in Burlington of an infectious fever, probably pneumonia. His eldest son, George Hobart, became the vicar general of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Newark and another, William Croswell, was the first Episcopal bishop of Albany, New York.

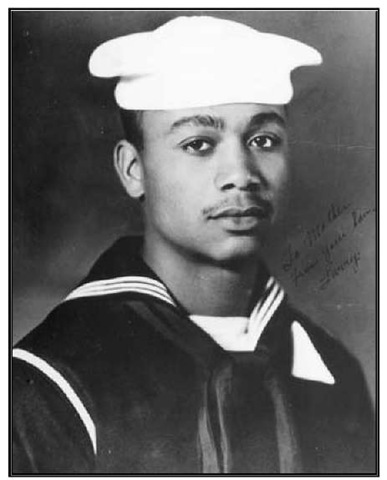

Doby, Lawrence Eugene (b. Dec. 13, 1924; d. June 18, 2003). Professional baseball player. Born in Camden, South Carolina, Larry Doby was raised in Paterson from the time he was eight years old. An outstanding athlete at Paterson’s Eastside High, he briefly attended Long Island University on a basketball scholarship. Before finishing, he joined the navy and served during World War II. Upon returning home, Doby focused on baseball and quickly became a standout for the Newark Eagles of the Negro League. As a power hitter and star second baseman, he lead the Eagles to their 1946 championship. In July 1947, just months after Jackie Robinson’s debut, Doby became the second African American in Major League Baseball when he was called up to the Cleveland Indians. Moving from infield to outfield, Doby went on to achieve a series of milestones for African Americans in baseball: first in the American League, first American League home run leader, first to play on a World Series championship team, and first to hit a World Series home run. He played in every All-Star Game from 1949 to 1955. After retiring, Doby coached for the Montreal Expos and Cleveland Indians. He took over as manager of the Chicago White Sox mid-season 1978, becoming the second African American to hold such a position. Doby was elected into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1998.

When Paterson’s Larry Doby left the Negro League to serve in the South Pacific during World War II, he sent this picture home to his mother.

Dodge, Geraldine Rockefeller (b. Apr. 3, 1882; d. Aug. 13, 1973). Philanthropist. The youngest child of William and Almira Rockefeller and niece of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge was born to wealth and social position resulting from her father’s presidency of Standard Oil of New York and his successful investments. She was edu-catedatMiss Spence’s, a progressive New York school for women founded in 1892. On holidays, she traveled to family homes at Mount Pleasant, New York; Jekyll Island, Georgia; and Bay Pond in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. Extended vacations were spent traveling throughout Europe.

In 1907, Geraldine married Marcellus Hartley Dodge, scion of the Remington Arms Company. The Dodges settled in Morristown and in 1916 purchased Onunda, an estate in Madison. Geraldine changed its name to Giralda, after Saint Geraldo, the Spanish patron of orphans, and there she began to pursue various interests, including dog breeding and collecting primarily historical art and an-imalier bronzes. Her state-of-the-art kennels became world-renowned. She cofounded the Morris and Essex Kennel Club, and from 1927 to 1957, she sponsored the club’s annual dog shows at Giralda. In 1939, Dodge established Saint Hubert’s Giralda (an animal shelter), and during the 1940s, she wrote books about German shepherds and cocker spaniels. Her generous donations to animal research contributed to the prevention and treatment of disease.

In August 1930, the couple’s only son, Marcellus Hartley Dodge, Jr., was killed in an automobile accident in France during a post-Princeton University graduation vacation. Devastated by the loss, Dodge decided to underwrite the construction and furnishing of a new Borough Hall in Madison in her son’s memory. In 1963, her husband died. At her death a decade later, Geraldine left the bulk of her estate to establish the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, which continues to provide support for animal welfare, the arts, local Morris County projects, as well as education and environmental causes.

Friedrich August von Kaulbach, Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, 1906. Oil on canvas, 33 1/2 x 30 in.