In addition to font families, there are additional parameters that allow you to personalize the text that you should take into consideration. Let’s define a few more terms:

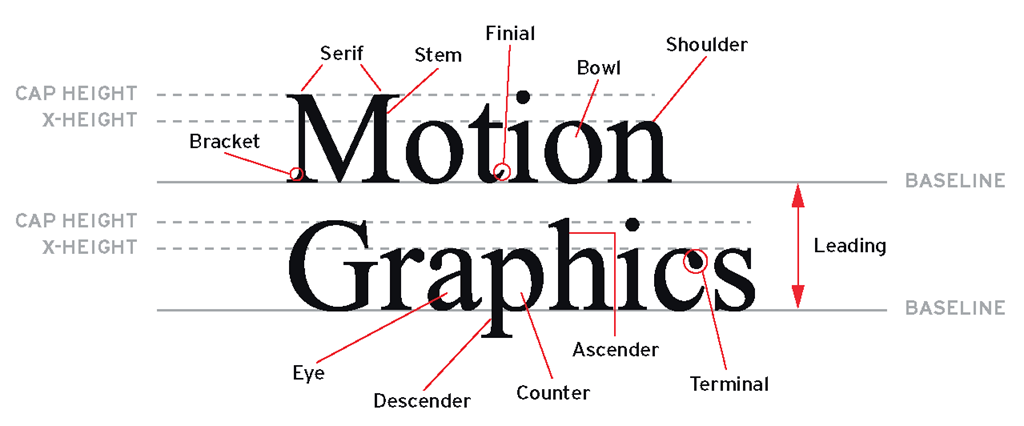

• Baseline. The invisible horizontal line that all letters rest on. This is the line across the bottom of the x-height. The curves of some letters, descenders, and punctuation marks often go below the boundaries of the baseline.

• Kerning. Kern is the measure of space between two characters. Kerning is the process of reducing or increasing the space between specific pairs of characters. Although it might seem appropriate to check the kerning throughout your titles, it could quickly become a time-consuming activity, especially when you’re under a tight timeline. While you could be forgiven for not checking your end titles, you should absolutely check your main title card and single/double title cards for any necessary kerning adjustments. When doing so, pay attention to how each letter looks adjacent to the previous or the following one and try to make spacing consistent between each letter.

Figure 3.4 Example of bad (top) and good (bottom) kerning.

Depending on the letters, the space should be reduced or increased. Common characters that require some kerning adjustments include uppercase letters that have a diagonal shape followed by a curved one or another diagonal one. To get more accustomed to this thought process, consider looking at the negative (white) space between each letter and try the following:

• Manipulate it to make it of an equal mass within similarly shaped letters (e.g., straight/round, straight/straight, round/round letters).

• Once you’ve established your point of reference, keep the negative space consistent throughout your title cards.

• Avoid letting serifs touch each other.

Some typefaces require more attention than others. Generally, well-designed typefaces from a well-established font foundry require minimal kerning adjustments. Kerning requires practice, time, and attention to detail. Keep in mind that well-kerned type generally goes unnoticed, but to a trained graphic designer’s eye, badly kerned type jumps off the screen immediately. Depending on the software you use to create your title cards—such as Adobe InDesign, Illustrator, or After Effects—you might be able to control your kerning via the following options:

• Metric kerning (or auto kerning). This adjusts the kerning based on settings originally designed by the type foundry. Metric kerning refers to the font’s built-in kern pair tables and is generally the default setting.

• Optical kerning. This involves adjusting the kerning based on the actual shape of each letter. This option helps you save time while initially creating the layout of your text, but this should not be a substitute for your own judgment. You should still consider doing manual tweaks after you’ve applied optical kerning.

• Manual kerning. This involves adjusting the kerning manually, allowing you to choose a preset kern value or type in your preferred one.

• Tracking (spacing). The process of reducing or increasing the space between letters in words or blocks of text. Tracking can be tight or loose. Tightening or loosening the tracking decreases or increases the overall spacing throughout the selected words or block of text by the same proportional amount. When text is tracked too tightly, the words appear crowded and touch each other, and as a result it is difficult to read. On the other hand, when the text is tracked too loosely, it presents too much white space between the words, which makes it hard to read as well. Similarly to kerning, appropriate tracking comes with practice and experience.

Figure 3.5 selecting a kerning option.

Appropriately tracked text should go unnoticed by viewers. In tracking, follow these guidelines:

• Condensed or compressed typefaces generally require less tracking than wider typefaces.

• Smaller font sizes generally require more tracking than larger font sizes.

• Ascender. The part of a lowercase letter that stems up from its body, such as in the letters l or b.

• Descender. The part of a lowercase letter that stems down from its body, such as in the letters p or q.

• Leading (pronounced ledding). The distance between the baselines of a type that spans two or more lines of text. When you’re setting the leading for your titles, especially when you’re designing a double card or scrolling titles, pay particular attention to the ascenders and descenders and make sure they don’t touch.

Figure 3.6 Examples of a typeface’s properties.

Exercise: a Typographic narrative

Objective: Animate one quote from a song, poem, or movie excerpt in a way that enhances its meaning. process: Pick a meaningful quote (don’t forget to include the quote’s author!), and focus on color(s), typeface, and camera movement to visually represent each quote in the animation.

Think of each word as individual characters. Are there any lead actors? Who are the supporting actors? How do they relate to each other? Do they interact with each other or do they stand alone?

Consider these elements in your composition: depth, scale, repetition, characters’ relationships, readability, and screen time. Arrange your composition so that you direct the viewer’s attention to a particular word when you plan it to be read, especially when multiple words appear on your screen at the same time.

Allowed assets:

• Type

• Colors

• Shapes

• Illustrations

• Video

• Audio

Technical requirements/specs:

• 720 x 540 square pixel composition

• At least 15 seconds of animation

• Motivated color

• Motivated type

• Motivated camera movement Restrictions:

• Maximum of two font families

Which "Type" are You?

• Type 1 (or PostScript). Originally developed by Adobe in the 1980s, Type 1 fonts include two components: an outline font and a metrics font, both necessary to print the font. This type of font is particularly preferred by Mac users because of the multitude of quality typefaces available, and also by print facilities because it allows a detailed and high-quality print of the font at any size and creates less technical trouble, since most of them use the same computer language (PostScript) to output their files.

• TrueType. Developed by Apple and Microsoft working together, TrueType fonts include only one file necessary to both display and print them. This type of font is particularly preferred by Windows users in that certain standard TrueType fonts, which are included in most operating systems, offer the user digital "hints” to improve the font’s clarity, especially when they are used in small point sizes.

• OpenType. Developed by Adobe and Microsoft together, OpenType fonts are cross-platform compatible (the same font files work on both Mac and Windows computers) and support an expanded character set—a typical Type 1 set contains 256 characters; OpenType can contain up to 65,000 characters, including ligatures, dingbats, and alternate glyphs.

On the Web Take a look at the following Web sites to see what’s out there.

Useful type Web sites:

• www.dafont.com/

• www.typographica.org

Type ID forum:

• www.typophile.com/forum/

Useful type foundries’ Web sites:

• www.fontshop.com/fonts/

• http://typography.com/

• www.typophile.com/

• www.fonthaus.com/

• www.houseind.com/

• www.emigre.com/