The cosmologies, religions, and spiritual traditions of Africa, a continent that includes more than 50 sovereign nations, represent thousands of linguistic groups and cultural communities that have developed over tens of thousands of years. Continental Africa is the locus of indigenous, vernacular expressions of the sacred including divination, ancestor worship, supernatural phenomena—particular forms of witchcraft, for example—and pantheistic traditions, among them the origins of contemporary New World Vodun, Afro-Caribbean Santeria, Brazilian Candomble, and Afro-Brazilian Um-banda. African religious practice also includes traditions that began outside of Africa, such as Judaism (the Abuyudaya Jews of Uganda, Ethiopian Jewry, and the Lemba people of Zimbabwe who claim to be one of the lost tribes of Israel), Christianity (beginning with the New Testament conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch in the Acts of the Apostles), and Islam (beginning with the military campaigns of General Amr ibn el-Asi who carried the Middle Eastern religion to Alexandria, Egypt, in 639). In addition, there are very small groups of practicioners of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Baha’i (Barrett, 2001). The forms that these large, non-African religions have taken involve syncretism in the Africanization of the Abrahamic traditions as well as the Christianization and Islamicization of Africa. Traditional indigenous religions have continued in both inherited and new forms at the national and regional levels; these have often mixed with spiritual expressions from other sources to create significant hybrids. The 1977 film, The Long Search, traces the commingling of Christian and traditional religious elements within the Zulu Zion churches of Southern Africa, an interplay attested to and encouraged in a number of papal letters to African Bishops’ synods.

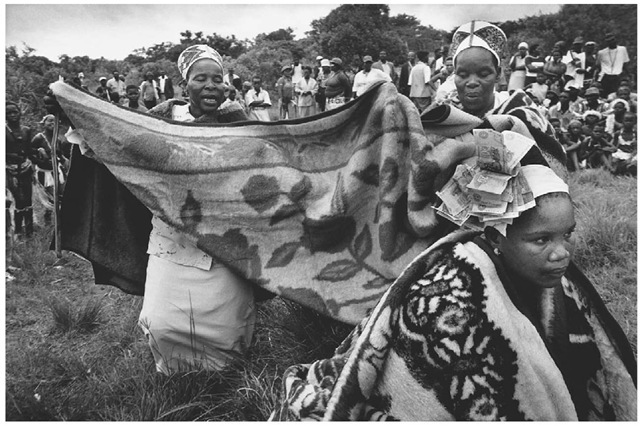

Traditional Zulu engagement ceremony.

In addition to the outline and observance of ritual and worship, some of the various traditions share, in different degrees, systems of cosmology, philosophy, dogma, doctrine, sacred writings or oral expression, rules of community engagement, and ethical practice. The latter have to do with corporate as well as personal action, including appropriate and ideal systems of human interaction. Love in its myriad forms —agape, philia, eros, the sacred, the communal, and the patriotic—is one of the areas of human conduct present in several of these traditions even as the very definition of “love” has undergone metamorphoses as a result of colonial histories. Much African literature has taken on the intersections between and among religious traditions and varying definitions and expressions of love. There is an entire genre of African fiction, for example, known as the “missionary novel” that tackles such thorny issues as colonization, miscegenation, deracination, the death or continuity of culture, gender roles, and legal proscription using the intersection of love and religious expression as its thematic vehicle. Insofar as love represents the phenomenon of encounter, writers can address multiple layers of pleasure, genteel seduction, rape, and prostitution—and the critique of some of these activities by the religious establishment—as an indirect way of interrogating the colonial and neo-colonial adventures themselves.

The concept of romantic love probably comes to mind first in considerations of the interaction between culture and religion with regard to marked manifestations of passion. Usually attributed to Christian and Western colonization, romantic love has long been associated with cultural imposition and disruption, on the one hand, and an extra-utilitarian view of human mating. However, some scholars have called into question the axiom that romantic love is a Western construct and experience exported to other parts of the world, differentiating between the presence of cultural language for the actual experience of passion and belief in the reliability of romantic love as a determining factor in the selection of a spouse (Jankowiak, 1992).

Anthropologist Geert Mommersteeg’s detailed study, He Has Smitten Her to the Heart with Love: The Fabrication of an Islamic Love-Amulet in West Africa, traces in great detail the creation of such an amulet with inscriptions in Arabic from the Qur’an. It was believed that such a charm could protect the beloved wearer from danger. As Mommersteeg points out in another essay two years later, however, Allah’s words themselves are an amulet.

Specifically linking erotic love to the symbiosis of political and religious colonization in Africa reveals a good deal about cultural pressure points, the processes of historical change and transformation, the idiosyncratic translation, transmission, and reception of religious dogma and ideology in individual countries or among particular cultural groups; and the eclecticism that characterizes the African continent. African authors, such as novelists Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, discuss how the tensions between Christian evangelization and African traditions impact the expressions of love in indigenous communities. In Thiong’o's work, indigenous bodily modifications that mark women as mature and beautiful to their communities are largely condemned by both African and non-African Christians, resulting in a religious and cultural dilemma for women wanting to express community affiliation while remaining Christian (Thiong’o, 1965). Four decades later, Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus recounts the experience of another household of desiccating, spirit-killing religiosity behind the frangipani trees in a rigidly Catholic compound against the backdrop of repressive political challenges in contemporary Nigeria (Adichie, 2003).

Students of African religion have pointed to cultural practices regarding marriage as an excellent ground for the study of inconsistent colonial impositions of approved social polity, African resistance strategies, and hybridizations of traditional and colonial practice. In 1910, the Protestant World Missionary Conference at Edinburgh pinpointed a gradual, initially tolerant, critique of polygamy that reaches “a crescendo of condemnation.” The meeting minutes assert: “Our correspondents in Africa view with unanimous intolerance conditions of life which are not only unchristian, but are at variance with the instinctive feelings of natural morality.” Polygamy is labeled “one of the gross evils of heathen society which, like habitual murder or slavery, must at all costs be ended” (Hastings, 1994). Some Christian pastors refused baptism to practicing polygamists. Others, concerned about the seeming concubinage into which formerly licit wives and their children were reduced, talked about polygamy as a transitional step toward a monogamous ideal that Lutheran theologians, including Luther, could not defend as a scriptural proscription. It is not unusual, among the educated elite in a nation such as Nigeria, for the bride and groom to participate in “the white wedding,” the Christian ceremony in church, while observing the traditional inter-familial religious rites of blessing and commitment.

The critique of a merely binary view of Africa and Africans has been a staple of the cultural production of so many national literatures on the continent. There is Chinua Achebe’s famous poetic caveat—”Beware soul brother / of the lures of ascension day”—even as the text expresses a willingness to dance the dances of Passion Week if one goes to them with one’s own abia drums. Those who otherwise control the song are both tone deaf and leaden-footed; there is, moreover, an integral and indivisible connection between and among “song,” “soil” and “soul.” 1986 Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka makes provocative comedy of the assumption of easy divide in his sexually titillating play, The Lion and the Jewel (1963). Using a problematic focus on the maidenhead of the young Sidi, the schoolmaster, Lakunle, assumes that he can easily best his contender, the old Bale— Baroka. Amidst clever wordplay it is apparent that tradition continues to retain potency.

Literal impotence can accompany a calculating misuse of religiously sanctioned sexual contracts built on a blend of traditional polygamous practice and Islamic law. The brilliant novelist-turned-filmmaker, Ousmane Sembene, tells, at first in novel form in Xala (1974) and later in the 1975 film by the same name, the story of an Islamic Senegalese businessman, Aboucader, known as El Hadji, who decides to take a third wife as a neo-colonial extension of his financial holdings and social capital. The young girl is a literal commodity; his selfish acquisition of her results in a series of comedic fumbles and his being cursed on his wedding night with xala (impotence). Working within the genre of satire, Sembene’s work is political commentary writ large, as El Hadji undergoes a series of absurd and comedic “treatments” in order to restore his sexual power. In the final moments of the film he is literally covered by the multicolored spittle of the community beggars.

There are certain kinds of loves that can lead to alienation. In The Ambiguous Adventure (1961), Cheikh Hamidou Kane’s classic study of the young Senegalese Qur’anic scholar forcibly turned into a student of philosophy at the Sorbonne, is one case in point. Sambo Di-allo, a member of the Diallobe aristocracy, is the most intellectually gifted of the students of the Prophet. French colonist-educators, recognizing those gifts of mind, are instrumental in a change of the focus of study; Sambo himself becomes attracted to the scientific method. He eventually journeys to Paris to deepen his understanding and appreciation of French philosophy. Such interrogation in the agnostic milieu of the French academy queries Sambo’s Islamic faith and practice. He can not belong to France or to Senegal, but recognizes that “I have become the two.” The text itself becomes noticeably less lyrical and more analytic, as if the language itself represents the intellectual and affective processes of change Sambo himself experiences. Winner of the 1962 Grand Prix de l’Afrique Noir, the novel ends with the death of the protagonist as he disparages prayer. As his life ebbs from him, the lyric beauty of the text returns and the reader is left with a number of unanswerable questions about the value of the colonial enterprise.

Very often the matter of love—in its various forms—is the vehicle for such complex philosophical explorations. Using satire in one of Francophone Africa’s funniest exemplars of the missionary novel, Cameroonian Mongo Beti (pen name for Alexandre Biyidi) tells the story of Essazam Village where, in the space of a few minutes in 1948, an apparently dying Chief is baptized by his over-zealous Aunt Yosifa. When the Chief recovers, the immediate question is whether or not it is baptism that is responsible for the miracle; he does not want to take any chances. In King Lazarus (1971), Chief Essomba Mendouga decides that he must change his life in order to live in accordance with the religious and ethical practices of the new religion. A polygamist until the baptism, the Chief makes the pious choice to follow monogamy as the husband of his youngest wife, thereby declaring the other twenty-two concubines without the protection of social status and financial stability for themselves or their children. The world erupts into mutiny and the text into the merciless philosophical and linguistic play of irreverence. Le Guen, the ardent missionary-priest, is described accordingly: “His long beard was full of leaves and other vegetable matter; his shoes clogged with grey mud. Every few yards he rested. He dragged an enormous stem of bananas, possibly heavier than the cross at Golgotha.”

A renaissance in attention to African traditional religions has been both substantive and methodological. As Noel Q. King pointed out almost 40 years ago in Christian and Muslim in Africa, contemporary African “theologians are seeking to understand what African Traditional Religions, through exorcisms and the treatment of psychosomatic disease, are trying to tell Christians.” One of the most public examples of this yoking of the traditional with the highly structured metropolitan religion of the colonial encounter is in the case of the excommunicated, former Catholic Bishop of Lusaka, Emmanuel Milingo. Censured for the use of faith healing and condemned by some of his critics as a practitioner of witchcraft, Milingo was pressured into resigning his episcopal post. His own perspective on Africanized Christianity also involved the matter of love with regard to the “discipline,” as he indicated, rather than the “dogma” of mandatory clerical celibacy. The excommunication of Bishop Milingo, himself a married man, followed on the heels of his 2006 ordination of four other married men as bishops. In Zambia, the Movement for Married Priests, founded by the excommunicated bishop, has encouraged married clergy—as of the summer of 2007— to celebrate the Mass in public settings.

In that contemporary public realm, there are restrictions on some kinds of performance associated with the erotic. Popular culture, represented, for example, by Afropop, has to bow, in some places, to formal censorship. The government of Egypt insists on the approval by official censors of pop songs before they are marketed, while Algerian artists and producers face death sentences for candid lyrics about alcohol consumption or erotic love.

A controversial employment of love at the opposite end of a continuum yoking agape and eros was the heavily Christianized Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the brain child of former South African President Nelson Mandela and Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. With the intent of forestalling a bloodbath easily enough precipitated by long generations of repression, torture, and state-sponsored murder, the two South African leaders hoped to create a permanent record of the atrocities of the apartheid regime and to move the nation a generation early toward reconciliation. Redeploying an ancient African word, “ubuntu,” the Archbishop Emeritus describes its charged meaning in the contemporary moment. “Africans have this thing called ubuntu,” he maintains. “It is about the essence of being human; it is part of the gift that Africa will give the world. It embraces hospitality, caring about others, being able to go the extra mile for the sake of others. . . . We believe that my humanity is caught up, bound up, inextricably with yours.” One of the most moving demonstrations of this way of seeing has been the renowned work of TRC Commissioner and clinical psychologist, Pumla Gobodo-Madik-izela, in A Human Being Died That Night (2003). While there are differences in understanding among the Abrahamic communities of faith about what constitutes forgiveness and whether or not forgiveness can be given by anyone other than the injured party, the compassionate appeal to ubuntu has a continental resonance.