"ALEXANDER OF APHRODISIAS

(end of second century-beginning of third century c.E.), Greek philosopher, commentator on the writings of *Aristotle, and author of independent works. Alexander was important for his system-atization of Aristotle’s thought and for the formulation of a number of distinct doctrines, especially in psychology. A number of his commentaries and independent works were translated into Arabic, and the views contained in them became an important part of medieval Islamic and Jewish Ar-istotelianism. The first book of Alexander’s On the Soul was translated into Hebrew by Samuel ben Judah of Marseilles from the Arabic translation made by H unain ibn Ish aq. This translation, which contains brief annotations, was completed in 1323 in Murfa and a revised version of it was finished in 1339-40 in Montulimar.

Alexander, it was commonly thought, wrote a second book in psychology, called Treatise on the Intellect, and it circulated in Arabic translation. Averroes wrote a commentary to this work that was translated into Hebrew and is extant in manuscript only with the supercommentaries of *Moses b. Joshua of Narbonne (1344) and Joseph b. Shem Tov *Ibn Shem Tov (1454). H.A. Davidson edited the Averroean portions of the commentary themselves, without these supercommentaries, in 1988.

*Maimonides’ estimation of Alexander may be gathered from a famous letter which he wrote to Samuel ibn *Tibbon. Evaluating the philosophical literature of the day, Maimonides advises his translator that for a correct understanding of Aristotle’s teachings he should read, beside the commentaries of *Themistius and Averroes, also those of Alexander (A. Marx, in jqr, 25 (1934/35), 378). Maimonides used works by Alexander in the composition of his Guide, and Alexander’s views formed part of Maimonides’ own brand of Aristotelianism (for details see S. Pines, "Translator’s Introduction," Guide of the Perplexed (1963), ixiv-ixxv). Maimonides cites Alexander as his source for his discussion of the factors which prevent man from discovering the truth (Guide 1:31), for his account of the celestial motions and intelligences (2:3), for his knowledge of the views of certain Greek philosophers (2:13), and for his discussion of God’s knowledge (3:16). Alexander may also have influenced Maimonides’ views on religion and political history, particularly the view that God used "wily gracious-ness" in bringing man from inferior forms of worship to more adequate ones (3:32).

Of special importance for Jewish philosophers was Alexander’s doctrine of the intellect, discussed in detail particularly by *Gersonides (Wars of the Lord, Book 1). Aristotle’s views (especially De Anima 3:5) were rather enigmatic. Central to Aristotle’s discussion was the distinction between the agent intellect (nouspoietikos) and the passive intellect (nouspathe-tikos). Interpreting Aristotle’s views, Alexander held that the agent intellect did not form part of the individual human soul, but was identical with the intellect of God; while the passive intellect belonged to the soul as a mere predisposition or ability for thought. The passive intellect was also called material or hylic intellect (nous hylikos), and when actualized by the agent intellect became the acquired intellect (nous epiktetos) or intellect in habit (nous kath’hexin). The passive intellect, according to Alexander, being part of the individual human soul, is, like it, mortal; only the acquired intellect is immortal, insofar as the objects of its thought are the immaterial beings, in particular, God. While Alexander’s doctrine of the intellect was more precise than that of Aristotle, it contained enough ambiguities to give rise to further refinements on the part of Islamic and Jewish philosophers.

Jewish, as Islamic, philosophers accepted Alexander’s notion of the agent intellect, but instead of identifying it with God, they identified it with the lowest of the celestial intelligences, which, on the one hand, governs the sublunar world, and, on the other, is a causal agent in the production of human knowledge (see also *cosmology). The agent intellect is also important to Jewish Aristotelians for its roles in the production of prophecy. While there was general agreement about the nature of the agent intellect, there was disagreement about the nature of the passive one. Alexander’s acquired intellect became a commonplace in Jewish philosophy, though the medievals refined this notion by distinguishing between the intellect in actuality, and the acquired intellect. Medieval philosophers disagreed about the exact nature of the acquired intellect, but it became important for their doctrine of the immortality of the *soul and the world to come (for details see *Intellect, Doctrines of).

"ALEXANDER OF HALES

(d. 1245), English scholastic philosopher and theologian. Alexander joined the Franciscan order after 1230, while teaching at the Faculty of Divinity in Paris. Since he did not complete his comprehensive work, Summa universae theologiae (4 vols., 1481-82; 1924-48), which was first edited by his pupils, the extent of his responsibility for the attitudes and opinions expressed in it, and according to which his personal character has been traced, remains controversial. The section on Jews in Christian society confirms the ecclesiastical tradition of restricted toleration. The existence of the Jewish people serves as lasting witness to the origins of Christianity; their conversion at the end of days, according to the teaching of St. Paul, will mean the conclusion of mankind’s salvation. Therefore, a definite distinction is drawn between the believers in the Old Testament and the Saracens, who then occupied the Holy Land. Obviously, this remark had a topical relevance in the period when Louis ix was preparing another Crusade. Jewish blasphemies against Christ must be severely punished, if made in public, but not more severely than those committed by Christians. Books containing such utterances must be burned.

Alexander’s Summa originated at a time when the Talmud and post-biblical Jewish literature were under attack. Thus, although the Summa uses *Maimonides’ Dux neutrorum (Guide of the Perplexed) as a source of philosophical doctrine, especially in the discussion of cosmological questions, the author was reticent in identifying the source of his doctrines. Jacob Guttmann found Maimonides mentioned only twice, although soon afterward his name became a household word among the masters of the schools. Most striking is the use of Maimonides’ reflections on the meaning of biblical commandments, intended to affirm the Old Testament’s character as divine revelation, in opposition to the dualistic theories of contemporary heretics. In this context "Rabbi Moyses Judaeus" is mentioned by name with his differentiation of judicia and caerimonialia. This interest in the teachings of the third book of the Dux (Guide) prepared the way for *Aquinas’ interpretation of Deuteronomy as the model of his social theory. Alexander was also influenced by Ibn *Gabirol (Avicebron), although he does not mention this philosopher by name.

"ALEXANDER POLYHISTOR

(first century b.c.e.), Greek scholar. Alexander was born in Miletus in Asia Minor. He was taken prisoner by the Romans, but was later freed, and continued to live in Italy as a Roman citizen until his death (c. 35 b.c.e.). He was called Polyhistor (very learned) because of the wide variety of subjects on which he wrote. His works included three volumes on Egypt, one on Rome, and a work entitled "Concerning the Jews." This last work reflects the growing Roman interest in the Jewish people at the time of Pompey’s conquest of Judea. Lengthy fragments from this work have been preserved by *Eusebius (Praepara-tio evangelica, 9), and by Clement of Alexandria. From these it seems apparent that he combined relevant excerpts from Jewish, Samaritan, and gentile writers and reproduced them in indirect speech. Thus, valuable fragments of the writings of Hellenistic-Jewish authors have been preserved of which nothing would otherwise be known. Alexander cites the historians *Aristeas, *Demetrius, *Eupolemus, and *Artapanus, the tragic poet *Ezekiel, the epic poets *Theodotus and *Philo the Elder, as well as non-Jewish writers such as the historian Timochares, author of "The History of Antiochus," and *Apol-lonius Molon.

It seems that Alexander made little original contribution to the subject. In his works he made indiscriminate use of traditions both favorable and hostile to the Jews. He also dealt with the Jews in other works. In his book on Rome he states that a Jewish woman named Moso wrote the Law of the Hebrews, i.e., the Torah (see Suidas, s.v. AAe^avSpoi; o MiX^aio^). Although Alexander was fully aware of the Jewish tradition concerning Moses, he appears to have seen nothing wrong in quoting a conflicting tradition from a non-Jewish source. His explanation that Judea was named after one of Semirasis’ sons must have been taken from a similar source (quoted in Stephanus Byzantinus’ exposition on Judea).

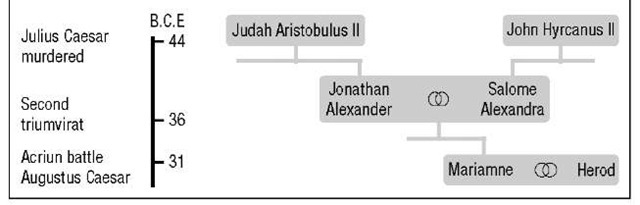

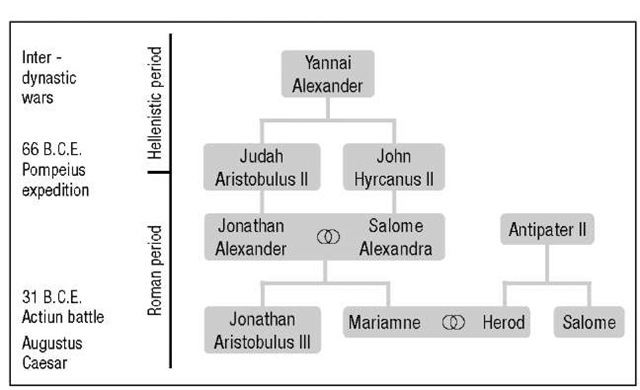

ALEXANDER SON OF ARISTOBULUS II

(d. 49 b.c.e.), one of the last of the *Hasmoneans. Alexander, eldest son of Aristobulus ii, was the son-in-law of *Hyrcanus ii. His wife, *Alexandra, was the mother of *Mariamne, wife of *Herod the Great. As a result of the struggle between Aristobulus ii and Hyrcanus ii for the throne of Judea, Alexander was sent by Pompey in 63 b.c.e. as a captive to Rome – with his father and the rest of his family. He escaped on the way and returned to Judea, where he succeeded in mustering an army of 10,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry, and in occupying the strongholds of Alexandreion, Hyrcania, and Machaerus. *Gabinius, recently arrived in Syria as proconsul, collected a force to oppose him and sent his adjutant Mark Anthony ahead. Anthony equipped an additional Jewish contingent under the Jewish commanders Peitholaus and Malichus. Gabinius defeated Alexander’s army in the vicinity of Jerusalem, and the remnant fled to Alexandreion. Besieging the fortress, Gabinius promised Alexander his freedom and an amnesty for his troops if he surrendered. His mother also pleaded with Alexander to accept this condition and he left Alexandreion which was then razed to the ground by Gabinius. Gabinius thereupon introduced a much more stringent administrative system than was in force earlier.

Alexander rebelled a second time in 55 b.c.e., when Gabinius was in Egypt. He again mustered a large force and began to drive the Romans from Judea. Gabinius returned and immediately advanced to meet Alexander. He employed *Antipater to persuade Alexander’s army to desert to Hyrcanus. Alexander, however, still had thirty thousand men left and he met in battle the armies of Gabinius and Hyrcanus at Mt. Tabor and was defeated. The defeat shattered Alexander’s resources. Antipater, however, succeeded in effecting a reconciliation between Alexander and Hyrcanus, by arranging a marriage between Alexander and Hyrcanus’ daughter Alexandra, which might eventually enable Alexander to become high priest. When civil war broke out in Rome between Julius Caesar and Pompey in 49 b.c.e., Pompey ordered his father-in-law Q. Caecilius Metellus Scipio, then proconsul in Syria, to put Alexander to death in Antiochia.

ALEXANDER SUSLIN HAKOHEN OF FRANKFURT

(d. 1349), German talmudic scholar. Alexander was born in Erfurt and taught there as well as in Worms, Cologne, and Frankfurt. Although he was apparently still in Frankfurt in 1345 he sometime toward the end of his life resettled in Erfurt where he died a martyr’s death. He is the last of the early German halakhic authorities. Alexander’s fame rests upon his Aguddah (Cracow, 1571; photostatic copy 1958; critical annotated edition, Jerusalem, 1966- ), a collection of halakhic decisions derived from talmudic discussions and arranged in the order of the tractates of the Talmud. It includes novellae (his own as well as those of some of his predecessors), and a commentary and collection of halakhot to the minor tractates and to the Mishnayot of the orders Zeraim and Tohorot. The language is very concise and it can be seen that he wrote it in great haste, under the stress of the expulsions and persecutions of his time. Indeed the purpose of the book is to give halakhic rulings in a concise form, ignoring differences of opinion, for a generation which was harassed and persecuted. His sources are *Mordecai b. Hillel ha-Kohen and *Aher b. Jehiel, and they often have to be consulted in order to understand him.Aguddah on the order of Nezikin, with notes by J.H. Sonnenfeld, came out in Jerusalem, 1899. The later halakhic authorities attached great value to his works; Jacob ha-Levi Moellin and Moses Isserles (in his glosses to the Shulhan Arukh) in particular regarded his decisions as authoritative, and quote from him, although they were aware of his sources. He was eulogized in a dirge Ziyyon Arayyavekh Bekhi (published in the addenda to Landshut’s Ammudei ha-Avodah (p. 111-iv)).

ALEXANDER SUSSKIND BEN MOSES OF GRODNO

(d. 1793), Lithuanian kabbalist. Alexander lived a secluded life in Grodno, never engaging in light conversation so as not to be deterred from study and prayer. Many stories were told about him. According to a well-substantiated one, several days before Passover in 1790, a Jewish victim of a blood libel was sentenced to death unless he agreed to convert. Alexander, afraid the condemned man would be unable to withstand the ordeal, obtained permission to visit him in prison, and persuaded him to choose martyrdom. The execution was scheduled for the second day of Shavuot; on that day Alexander left the synagogue in the middle of the service for the place of execution, heard the condemned man recite the prayer of martyrdom, said "Amen," and returned to the synagogue, reciting the memorial prayer for the martyr’s soul. The second incident relates that Alexander was imprisoned in a German town for soliciting money for the Jews of Erez Israel, as it was illegal to send money out of Germany. On being freed, he immediately resumed collecting, ignoring the danger involved.

Alexander’s most important work, Yesod ve-Shoresh ha-Avodah (Novy Dvor, 1782; corrected edition, Jerusalem, 1959), a book of ethics, touches upon many aspects of Jewish life. It is divided into 12 sections, the final section Shaar ha-Kolel, concluding with an account of the coming of the Messiah. According to the author, the basis of divine worship is love of God and love of the Jewish people. Alexander emphasizes that a Jew must be grieved at the contempt in which the God of Israel and the people of Israel are held among the Gentiles, who persecute the chosen people and then ask mockingly, "Where is your God?" He speaks often and with great sorrow of the desolation of the holy city of Jerusalem and of Erez Israel and extols "the greatness of the virtue of living in the Land of Israel." In Alexander’s view, the essence of observance is intent (kavvanah); the deed alone, without intention, is meaningless. For this reason, he insisted on clear and meticulous enunciation of each word in prayer, giving many examples of how words are distorted in the course of praying. He also laid down a specific order of study: Talmud, musar, literature, and then Kabbalah. He emphasizes the need for study of the geography of the Bible.

Alexander was rigid in the matter of religious observance, threatening violators with severe retribution in the hereafter. He asked every Jew to resign himself to "the four forms of capital punishment of the bet din" and in his will he ordered that upon his death his body be subjected to stoning. Yet the central theme of his work is "worship the Lord in joy." His ideas make Alexander’s writings closely akin to the basic tenets of H asidism and *Nahman of Bratslav said of him, "he was a H asid even before there was H asidism." In annotated prayer books, especially in those of the Sephardi rite, his Kavvanot ha-Pashtiyyut, the "intent" of the text of the prayers as set forth in the Yesod ve-Shoresh ha-Avodah, is appended to most of the prayers. He was deeply revered and as long as there was a Jewish community in Grodno, men and women went to pray at his grave. Descendants of his family who originally went by the name of Braz (initials for Benei Rabbi Alexander Zusskind) later assumed the name Braudes.

ALEXANDER THE ZEALOT

Joint leader, with *Eleazar b. Dinai, of an armed band of Jews during the administration of the Roman procurator Ventidius *Cumanus (48-52 c.E.). They led a punitive expedition after a group of Galilean Jewish pilgrims had been murdered while passing through Samaria on their way to Jerusalem to celebrate one of the festivals. Cumanus, bribed by the Samaritans, took no steps to punish the guilty parties. The Jews thereupon abandoned the celebration of the festival and, under the leadership of Alexander and Eleazar, attacked several Samaritan villages, "massacred the inhabitants without distinction of age and burnt the villages." After a show of force by Cumanus and entreaties by the Jewish leaders of Jerusalem the armed bands dispersed, the zealots returning to their former strongholds in Judea.

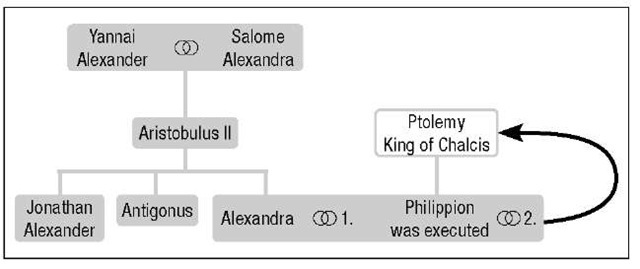

ALEXANDRA

Hasmonean princess, daughter of *Aristo-bulus 11, king of Judea. Captured by Pompey, Alexandra was brought to Rome in 63 b.c.e. together with her father, her two sisters, and her brother *Antigonus 11. The family was released in 56 b.c.e. and returned to Jerusalem. After the death of her father in 49 b.c.e., Alexandra was sent with Antigonus and her two sisters to Chalcis in Lebanon at the invitation of its ruler, Ptolemy, the son of Mennaeus. Alexandra married Ptolemy’s son, Philippion. But Ptolemy, jealous of his son, executed him, and then married Alexandra himself. Nothing more is known of her.

ALEXANDRA

(d. 28 b.c.e.), daughter of *Hyrcanus 11; wife of ^Alexander, the son of Aristobulus 11; and mother of Aristobulus ill and of *Mariamne, Herod’s wife. Alexandra regarded Herod’s appointment of the Babylonian (or Egyptian) Ananel (Hananel) to the high priesthood as a violation of the Hasmonean family’s right of succession to the office and attempted to secure it for her son Aristobulus. Though Herod acceded to her request, he was unable to forgive her, and did not allow her to leave the palace. When Alexandra tried to escape with her son, Herod foiled the attempt. He then affected a reconciliation. When, however, her son was drowned in a swimming pool, Alexandra accused Herod before Cleopatra of engineering his death and asked her to have Mark Antony charge Herod with the murder. Herod was summoned to Laodicea, but cleared himself by bribery.

After the battle of Actium (31 b.c.e.), it seemed certain that Herod could not escape punishment, since he had sided with Antony against Octavian (Augustus). When Herod returned from a meeting with Octavian with added honors, Herod’s sister Salome, Queen Mariamne’s implacable enemy, slandered her and Alexandra to her brother, and Mariamne was condemned to death for treason. According to Josephus’ biased account, Alexandra escaped the same fate by dishonorably accusing her condemned daughter of disloyalty to her husband. Her own fate was not long delayed. After Mariamne’s death Herod fell ill and appeared likely to die. Alexandra, thinking that her opportunity had now come, attempted to obtain control of the two fortresses in Jerusalem. When this was reported to Herod, he ordered her immediate execution. With Alexandra’s death, the last member of the Hasmonean dynasty to play an active role in history disappeared. Alexandra cannot be considered exceptionally sagacious or gifted with insight into Herod’s character. In all, she seemed to resemble her grandfather Alexander Yannai; she was courageous, but lacked flexibility and guile, and hence was no match for Herod.

ALEXANDRI

(Alexandrah, Alexandrai, Alexandros; third century), Palestinian amora. He was a leading aggadist of his day. Many of the scholars who quote Alexandri belong to the amoraim who centered around the academy at Lydda. It is therefore probable that Alexandri came from Lydda. It is related that he used to go about the streets of the town urging people to perform good deeds. He once entered the marketplace and called out: "Who wants life?" When the people answered him affirmatively he responded by quoting the verse: "Who is the man that desireth life … Keep thy tongue from evil, and thy lips from speaking guile. Depart from evil and do good; Seek peace and pursue it" (Ps. 34:13-15; Av. Zar. 19b). Many of Alexandri’s homiletical dissertations are based on the book of Psalms. "Break Thou the arm of the wicked" (Ps. 10:15) is quoted by him as an indictment of profiteering. From Psalms 16:10 he derived that whoever hears himself reviled and does not resent it deserves to be called pious (hasid). He also said: "When man uses a broken vessel he is ashamed of it, but not so God. All the instruments of His service are broken vessels, as it is said: ‘The Lord is nigh unto them that are of a broken heart’ (Ps. 34:19); or ‘Who healeth the broken in heart’" (Ps. 147:3, PR 25:158b).

He customarily concluded his daily prayers: "Sovereign of the Universe, it is known full well to Thee that it is our desire to perform Thy will, and what prevents us? The yeast in the dough (i.e., the evil inclination which acts as a fermenting and corrupting agent) and subjection to foreign rule. May it be Thy will to deliver us from their hand, so that we may be enabled to perform the statutes of Thy will with a perfect heart" (Ber. 17a).

No details of his life are known, except that his statement "The world is darkened for him whose wife has died in his days" (Sanh. 22a) may have had a personal application. Scholars by the name of Alexandri b. Haggai (b. H agra, b. H adrin), Alexandri "Kerovah" ("the hymnologist"), and Alexandri de-Zaddika ("the Just"), are mentioned in isolated talmudic passages and one of these may be identical with this Alexandri.

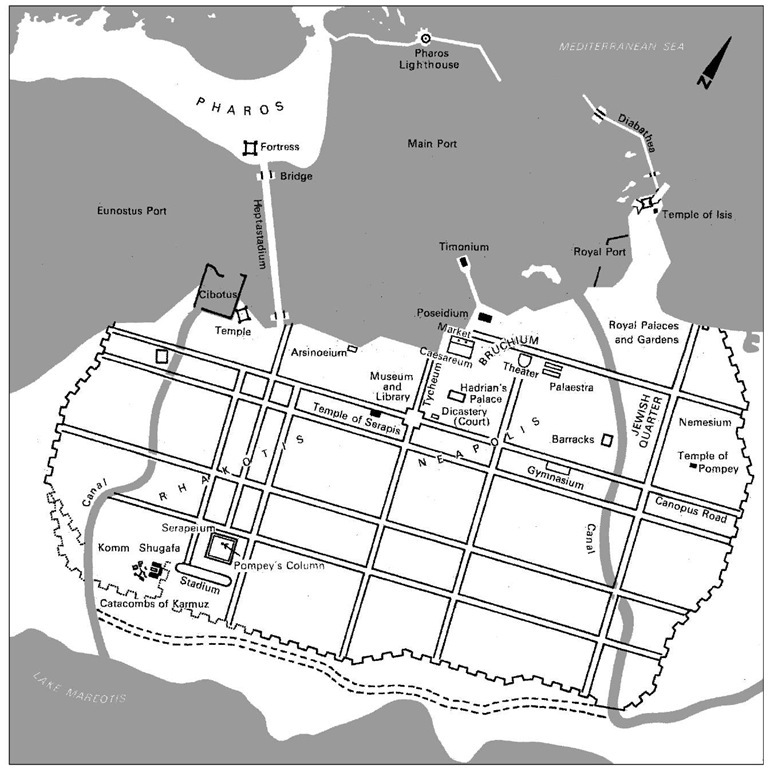

ALEXANDRIA

City in northern *Egypt. Ancient Period Jews settled in Alexandria at the beginning of the third century b.c.e. (according to Josephus, already in the time of Alexander the Great). At first they dwelt in the eastern sector of the city, near the sea; but during the Roman era, two of its five quarters (particularly the fourth (= "Delta") quarter) were inhabited by Jews, and synagogues existed in every part of the city. The Jews of Alexandria engaged in various crafts and in commerce. They included some who were extremely wealthy (moneylenders, merchants, *alabarchs), but the majority were artisans. From the legal aspect, the Jews formed an autonomous community at whose head stood at first its respected leaders, afterward – the ethnarchs, and from the days of Augustus, a council of 71 elders. According to Strabo, the ethn-arch was responsible for the general conduct of Jewish affairs in the city, particularly in legal matters and the drawing up of documents. Among the communal institutions worthy of mention were the bet din and the "archion" (i.e., the office for drawing up documents). The central synagogue, famous for its size and splendor, may have been the "double colonnade" (diopelostion) of Alexandria mentioned in the Talmud (Suk. 51b; Tosef. 4:6), though some think it was merely a large meeting place for artisans. During the Ptolemaic period relations between the Jews and the government were, in general, good. Only twice, in 145 and in 88 b.c.e., did insignificant clashes occur, seemingly with a political background. Many of the Jews even acquired citizenship in the city. The position of the Jews deteriorated at the beginning of the Roman era. Rome sought to distinguish between the Greeks, the citizens of the city to whom all rights were granted, and the Egyptians, upon whom a poll tax was imposed and who were considered a subject people. The Jews energetically began to seek citizenship rights, for only thus could they attain the status of the privileged Greeks. Meanwhile, however, *antisemitism had taken deep root. The Alexandrians vehemently opposed the entry of Jews into the ranks of the citizens. In 38 c.e., during the reign of *Caligula, serious riots broke out against the Jews. Although antisemitic propaganda had paved the way for them, the riots themselves became possible as a result of the attitude of the Roman governor, Flaccus. Many Jews were murdered, their notables were publicly scourged, synagogues were defiled and closed, and all the Jews were confined to one quarter of the city. On Caligula’s death, the Jews armed themselves and after receiving support from their fellow Jews in Egypt and Erez Israel fell upon the Greeks. The revolt was suppressed by the Romans. The emperor Claudius restored to the Jews of Alexandria the religious and national rights of which they had been deprived at the time of the riots, but forbade them to claim any extension of their citizenship rights. In 66 c.e., influenced by the outbreak of the war in Erez Israel, the Jews of Alexandria rebelled against Rome. The revolt was crushed by *Tiberius Julius Alexander and 50,000 Jews were killed (Jos., Wars, 2:497). During the widespread rebellion of Jews in the Roman Empire in 115-117 c.e. the Jews of Alexandria again suffered, the great synagogue going up in flames. As a consequence of these revolts, the economic situation of the community was undermined and its population diminished. See also *Diaspora.

Alexandrians in Jerusalem

During the period of the Second Temple the Jews of Alexandria were represented in Jerusalem by a sizable community. References to this community, while not numerous, can be divided into two distinct categories: (1) The Alexandrian community as a separate congregation. According to Acts 6:9, the apostles in Jerusalem were opposed by "certain of the synagogue, which is called the synagogue of the Libertines and Cyrenians and Alexandrians, and of them of Cilicia and of Asia." The Alexandrian synagogue and congregation are mentioned in talmudic sources as well: "Eleazar b. Zadok bought a synagogue of the Alexandrians in Jerusalem" (Tosef. Meg. 3:6;cf. t j Meg. 3:1, 73d). (2) References to particular Alexandrians. During Herod’s reign several prominent Alexandrian Jewish families lived in Jerusalem. One was that of the priest Boethus whose son Simeon was appointed high priest by Herod. Another family of high priests, the "House of Phabi," was likewise of Jewish-Egyptian origin, although it is not certain whether they came from Alexandria. According to Parah 3:5, Hanamel the high priest, who had been appointed by Herod in place of Aristobulus the Hasmonean, was an Egyptian, also probably from Alexandria. "*Nicanor’s Gate" in the Temple was named after another famous Alexandrian Jew. Rabbinic sources describe at length the miracles surrounding him and the gates he brought from Alexandria (Mid. 1:4; 2:3; Yoma 3:10; Yoma 38a). In 1902 the family tomb of Nicanor was discovered in a cave just north of Jerusalem. The inscription found there reads: "The bones of the sons of Nicanor the Alexandrian who built the gates. Nicanor Alexa."

Jewish Culture

The Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria were familiar with the works of the ancient Greek poets and philosophers and acknowledged their universal appeal. They would not, however, give up their own religion, nor could they accept the prevailing Hellenistic culture with its polytheistic foundations and pagan practice. Thus they came to create their own version of Hellenistic culture. They contended that Greek philosophy had derived its concepts from Jewish sources and that there was no contradiction between the two systems of thought. On the other hand, they also gave Judaism an interpretation of their own, turning the Jewish concept of God into an abstraction and His relationship to the world into a subject of metaphysical speculation. Alexandrine Jewish philosophers stressed the universal aspects of Jewish law and the prophets, de-emphasized the national Jewish aspects of Jewish religion, and sought to provide rational motives for Jewish religious practice. In this manner they sought not only to defend themselves against the onslaught of the prevailing pagan culture, but also to spread monotheism and respect for the high moral and ethical values of Judaism. The basis of Jewish-Hellenistic literature was the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Bible, which was to become the cornerstone of a new world culture (see *Bible: Greek translations). The apologetic tendency of Jewish-Hellenistic culture is clearly discernible in the Septuagint. Alexandrine Jewish literature sought to express the concepts of the Jewish-Hellenistic culture and to propagate these concepts among Jews and Gentiles. Among these Jewish writers there were poets, playwrights, and historians; but it was the philosophers who made a lasting contribution. *Philo of Alexandria was the greatest among them, but also the last of any significance. After him, Alexandrine Jewish culture declined. See also *Hellenism.

Alexandria in early Christian times.

Byzantine Period

By the beginning of the Byzantine era, the Jewish population had again increased, but suffered from the persecutions of the Christian Church. In 414, in the days of the patriarch Cyril, the Jews were expelled from the city but appear to have returned after some time since it contained an appreciable Jewish population when it was conquered by the Muslims.

Arab Period

According to Arabic sources, there were about 400,000 Jews in Alexandria at the time of its conquest by the Arabs (642), but 70,000 had left during the siege. These figures are greatly exaggerated, but they indicate that in the seventh century there was still a large Jewish community. Under the rule of the caliphs the community declined, both demographically and culturally. J. *Mann concluded from a genizah document of the 11th century that there were 300 Jewish families in Alexandria, but this seems improbable. The same is true for the statement of *Benjamin of Tudela, who visited the town in about 1170 and speaks of 3,000 Jews living there. In any case, throughout the Middle Ages there was a well-organized Jewish community there with rabbis and scholars. Various documents of the Cairo Genizah mention the name of Mauhub ha-Hazzan b. Aaron ha-Hazzan, a dayyan of the community in about 1070-80. In the middle of the 12th century Aaron

He-H aver Ben Yeshu’ah *Alamani, physician and composer of piyyutim, was the spiritual head of the Alexandrian Jews. Contemporary with *Maimonides (late 12th century) were the dayyanim Phinehas b. Meshullam, originally from Byzantium, and *Anatoli b. Joseph from southern France, and contemporary with Abraham the son of *Maimonides was the dayyan Joseph b. Gershom, also a French Jew. In this period the community of Alexandria maintained close relations with the Jews of Cairo and other cities of Egypt, to whom they applied frequently for help in ransoming Jews captured by pirates. A letter of 1028 mentions this situation; it also praises Nethanel b. Eleazar ha-Kohen, who had been helpful in the building of a synagogue, apparently the synagogue of the congregation of Palestinians that may have been destroyed during the persecution of the non-Muslims by the Fatimid caliph al-H akim (c. 996-1021). In addition to this synagogue there was a smaller one, attested to in various medieval sources that mention two synagogues of Alexandria, one of them called "small." The Jews of Alexandria were engaged in the international trade centered in their city, and some of them held government posts.

Mamluk and Ottoman Periods

Under the rule of the Mamluk sultans (1250-1517), the Jewish population of Alexandria declined further, as did the general population. *Meshullam of Volterra, who visited it in 1481, found 60 Jewish families, but reported that the old men remembered the time when the community numbered 4,000. Although this figure is doubtless an exaggeration, it nevertheless testifies to the numerical decrease of the community in the later Middle Ages. In 1488 Obadiah of Bertinoro found 25 Jewish families in Alexandria. Many Spanish exiles, including merchants, scholars, and rabbis settled there in the 14th-15th centuries. The historian *Sambari (17th century) mentions among the rabbis of Alexandria at the end of the 16th century Moses b. Sason, Joseph Sagish, and Baruch b. H abib. With the spread of the plague in 1602 most of the Jews left and did not return. After the Cossack persecutions of 1648-49 (see *Chmielnicki) some refugees from the Ukraine settled in Alexandria. During the 1660s the rabbi of the city was Joshua of Mantua, who became an ardent follower of *Shabbetai Z evi. In 1700 Jewish fishermen from *Rosetta (Rashid) moved to Alexandria and formed a Jewish quarter near the seashore, and in the second half of the 18th century more groups of fishermen from Rosetta, *Damietta, and Cairo joined them; this Jewish quarter was destroyed by an earthquake. At the end of the 18th century the community was very small and it suffered greatly during the French conquest. Napoleon imposed heavy fines on the Jews and ordered the ancient synagogue, associated with the prophet Elijah, to be destroyed. In the first half of the 19th century under the rule of Muhammad ‘Ali there was a new period of prosperity. The development of commerce brought great wealth to the Jews, as to the other merchants in the town; the community was reorganized and established schools, hospitals, and various associations. From 1871 to 1878 the Jewry of Alexandria was divided and existed as two separate communities. Among the rabbis of Alexandria in modern times were the descendants of the Israel family from Rhodes: Elijah, Moses, and Jedidiah Israel (served 1802-30), and Solomon H azzan (1830-56), Moses Israel H azzan (1856-63), and Bekhor Elijah H azzan (1888-1908). As a result of immigration from Italy, particularly from Leghorn, the upper class of the community became to some extent Italianized. Rabbis from Italy included Raphael della Pergola (1910-23), formerly of Gorizia, and David *Prato (1926-37). Later rabbis were M. *Ventura and Aharon Angel. During World War 1 many Jews from Palestine who were not Ottoman citizens were exiled to Alexandria. In 1915 their leaders decided, under the influence of *Jabotinsky and *Trumpeldor, to form Jewish battalions to fight on the side of the Allies; the Zion Mule Corps was also organized in Alexandria.

Modern Times

In 1937, 24,690 Jews were living in Alexandria and in 1947, 21,128. The latter figure included 243 Karaites, who, unlike those of Cairo, were members of the Jewish community council. Ashkenazi Jews were also members of the council. According to the 1947 census, 59.1% of Alexandrian Jews were merchants, and 18.5% were artisans. Upon the outbreak of the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, several Jews were placed in detention camps, such as that at Abukir. Most of the detainees were released before 1950. There were several assaults on the Jewish community by the local population, including the throwing of a bomb into a synagogue in July 1951. With *Nasser’s accession to power in February 1954, many Jews were arrested on charges of *Zionism, communism, and currency smuggling. After the *Sinai Campaign (1956), thousands of Jews were banished from the city, while others left voluntarily when the Alexandrian stock exchange ceased to function. The 1960 census showed that only 2,760 Jews remained. After the *Six-Day War of June 1967, about 350 Jews, including Chief Rabbi Nafusi, were interned in the Abu Za’bal detention camp, known for its severe conditions. Some of them were released before the end of 1967. The numbers dwindled rapidly; by 1970 very few remained and in 2005 just a few dozen, mostly elderly people.

Hebrew Press

The first Hebrew press of Alexandria was founded in 1862 by Solomon Ottolenghi from Leghorn. In its first year, it printed three books. A second attempt to found a Hebrew press in Alexandria was made in 1865. Nathan *Amram, chief rabbi of Alexandria, brought two printers from Jerusalem, Michael Cohen and Joel Moses Salomon, to print his own works. However, these printers only produced two books, returning to Jerusalem when the second was only half finished. A more successful Hebrew press was established in 1873 by Faraj H ayyim Mizrahi, who came from Persia; his press continued to operate until his death in 1913, and his sons maintained it until 1916. Altogether, over 40 books were printed. In 1907 Jacob b. Attar from Meknes, Morocco, founded another press, which produced several dozen books. Apart from these main printing houses, from 1920 on the city had several small presses, each producing one or two books. A total of over 100 books for Jews were printed in Alexandria, most of them in Hebrew, the others in Judeo-Arabic and Ladino. Most of them were works by eminent Egyptian rabbis, prayer books, and textbooks.

ALEXANDRIAN MARTYRS, ACTS OF

Genre of patriotic Alexandrian literature containing heavy overtones of antisem-itism. This is known also as the "Acts of the Pagan Martyrs" (mistakenly, since the martyrdom has nothing to do with religion). Fragments of this literature were first published at the end of the 19th century. At that time the fragments were understood to be of a strictly official nature, in effect the protocols of numerous trials of Alexandrian representatives before the Roman Caesars. These missions would inevitably end in the execution of the delegates, thus arousing further the Alexandrians’ hatred both of the emperor and his presumed allies, the Jews, although a number of specimens make no mention of their part in the proceedings. With the publication of additional fragments, this view was modified, and it is now accepted that "this genre has nothing to do with official documents, and the protocol form… is merely a literary disguise" (Tcherikover, Corpus, 2 (1960), 56).

The background for the various trials covers a period of 150 years. The earliest embassy is associated with *Caligula (37-41), the latest (Acta Appiani) probably refers to the emperor Commodus (180-192). However, the most widely discussed fragments are those belonging to the Acta Isidori et Lamponis (for literature see ibid., 66-67). Isidoros, the head of the gymnasium of Alexandria, launched a vigorous attack against the Jewish king *Agrippa 1, and summoned him before the court of Claudius. The dialogue between the emperor and Isidoros is heated. At one point Claudius refers to Isidoros as "the son of a girl-musician" (i.e., a woman of loose morals) whereupon the latter immediately rebuts: "I am neither a slave nor a girl-musician’s son, but gymnasiarch of the glorious city of Alexandria. But you are the cast-off son of the Jewess Salome!" (ibid., 8of.). Isidoros and his colleague Lam-pon were immediately sentenced to death. The trial probably took place in 41 c.E. (although many scholars favor 53), for in that year a series of debates on Jewish civic rights came before Claudius. It would be mistaken, however, to conclude from this document that all the Acts were aimed solely at arousing anti-Jewish sentiment. Tcherikover has shown clearly that an-tisemitism in the Acts "plays a secondary part only, the major theme of the work being the clash between the Alexandrians and Rome." The author’s main purpose was to ridicule the Roman emperors, and for this purpose it was often sufficient to allude to the alleged cordial understanding between the emperors and the Jews.

ALEXAS

Friend of Herod the Great (37-4 b.c.e.) and husband of Herod’s sister, Salome. Herod forced Salome to marry Alexas, after threatening her with open enmity if she refused. Apparently Alexas was among the dignitaries who became powerful under the patronage of the new Judean dynasty. According to Josephus, Herod gave Alexas instructions about the procedure to be followed after his death. Alexas seems to have wielded sufficient authority to secure the release of the prisoners whom Herod had ordered to be executed on the news of his death to insure that the nation would mourn. But the whole story is probably a malevolent legend without foundation. Alexas had a son named after him, but with the surname Helcias. This son, known as Helcias the "Elder" or "Great" (o ^eya^), was apparently among the important members of the house of Herod. He is also referred to as "Helcias the Prefect" (Ant., 19:353). By the third generation, the house of Alexas had already obtained Roman citizenship, for Helcias’ son was named *Julius Archelaus. Josephus states that he was "well versed in Greek learning," and Archelaus was therefore among the first to receive the historian’s works (Apion, 1:51).

ALEXEYEV, ALEXANDER

(1820-after 1886), apostate and Christian propagandist. He was born Wolf Nachlas into a hasidic family in Nezarinetz, Podolia, and became a Christian after his impressment into the Russian army. During his army service Alexeyev was made a noncommissioned officer for his zeal in persuading Jewish child conscripts to convert to Christianity. Later he became paralyzed and was discharged. Alexeyev was subsequently appointed to attend the *Saratov blood libel case (1853) as an expert. He wrote a pamphlet entitled "Do Jews Use Christian Blood for Religious Purposes?" (1886), which boldly defends the Jews against this particular accusation. Other writings, however, aimed at winning Jewish converts, attacked the Talmud and the rabbis in crude terms which made an impact at the time.

ALFALAS, MOSES

(late 16th century), preacher, lived in Tetuan, Spanish Morocco. Alfalas, in common with R. *Judah Loew of Prague, employed philosophical terms in his preaching, without retaining their accepted meaning. Many of his sermons were delivered in Salonika, and he probably lived there some time. His printed works are Ho’il Moshe (1597), 13 topics of homiletic treatment of the midrashic sayings that refer to the meaning of the Torah and the relationship between Israel and the Torah; Ba Gad (printed together with the above), which contains seven topics of homilies explaining the significance of the milah ("circumcision"); Va-Yakhel Moshe (1597), 25 homilies which he had preached in Venice, Salonika, Tetuan and other towns, including some homilies written by his students under his supervision. All three books include an index of contents and sources, compiled by Samuel ibn Dysoss.

ALFANDARI

Family originating in Andalusia, Spain, and claiming descent from the family of Bezalel of the tribe of Judah. After the Expulsion (1492) the family spread throughout the Turkish Empire and France. For many generations they were among the major scholars and communal leaders of Constantinople, Brusa (Bursa), Smyrna, Egypt, and Erez Israel. The first member of the family of whom there is knowledge is isaac b. judah, who died in Toledo (1241). jacob b. solomon of Valencia and Solomon Zarzah translated Sefer ha-Azamim, attributed to Abraham *Ibn Ezra, from Arabic into Hebrew. The name "Alfandery" was known in 1506 both in Paris and in Avignon, and, in 1558, in Lyons. Variants are "Alfandaric" and "Alfandrec." Members of the family lived in Egypt immediately after the Expulsion from Spain at the end of the 15th century; they were primarily merchants. A 1515 document from Cairo mentions the merchant david alfandari. isaac, who traveled to Yemen on business, also lived there. Later, several members of this family immigrated to Egypt from Portugal, while some Marrano members of the family remained in Portugal. obadiah (mid-17th century), apparently a member of the Egyptian branch of the family, was the last marketer for the woolen industry in Safed, where he was known as "chief of the artisans." His business failed as a result of the exorbitant demands made upon him by the authorities in Safed, he left for Egypt, and it was on a journey from Egypt that he was robbed and murdered (c. 1661). jacob (second half of 16th century), a noted scholar of the Turkish branch, was the father of two well-known rabbis, H ayyim and Shabbetai. h ayyim (the Elder; 1588-1640) was a noted scholar, communal leader, and dayyan in Constantinople, his birthplace. He wrote a great number of re-sponsa, four of which were in the possession of his grandson, Hayyim b. Isaac. Among his correspondents was Jacob di Trani. He also wrote commentaries to most of the talmudic tractates, as well as novellae on the Tur of Jacob b. Asher, but these have not survived. shabbetai, born c. 1590, achieved fame as a scholar in his youth, and corresponded with two of Safed’s great scholars, *Hiyya Rofe and Yom Tov *Z ahalon, with whom he developed close ties upon their visit to Constantinople. Hayyim the Elder’s son jacob *alfandari was one of the leading scholars of Constantinople. H ayyim’s other son, isaac Raphael (c. 1622-c. 1687), studied under Joseph Trani and about 1665 was appointed rabbi of one of the congregations in Brusa, a position he held until his death. Isaac Raphael, whom A.M. Cardoso met in Brusa in 1681, is purported by the latter to have expressed his belief in Shabbetai Z evi to him, but this testimony is spurious. Isaac Raphael wrote many responsa and corresponded with H ayyim *Benveniste, who lauded him highly. His son H ayyim b. Issac *Alfandari was a noted scholar. elijah b. jacob al-fandari (1670?-1717), rabbi and halakhic authority, was av bet din in Constantinople, where he was born and died. He fought Shabbateanism. His works include Seder Eliyahu Rabbah ve-Zuta (1719) on the laws of agunah and Mikhtav me-Eliyahu (1723), on the laws of divorce. Approximately at the same time there were in Salonika two scholars, both among the most distinguished of Solomon b. Isaac ha-Levi’s pupils: moses alfandari, scholar and pietist, and his brother isaac.

h ayyim alfandari, known as "Rabbenu" to distinguish him from the Elder, was a rabbi in Jerusalem. In 1758 he was included among the members of Judah Navon’s bet midrash, "Damesek Eliezer." He was also one of a delegation of the seven rabbis including H .J.D. *Azulai sent on a special mission to Constantinople (but getting no farther than Egypt) to oust the official representative of Jerusalem’s "Vaad Pekidei Erez Israel." Joseph alfandari (d. 1867), a dayyan and preacher in Constantinople, studied under Isaac *Attia, author of Rov Dagan. He wrote Porat Yosef (1868), responsa to which he appended his teacher’s responsa, and talmudic novellae, and Va-Yikra Yosef (1877), homilies with some re-sponsa.

solomon b. hayyim alfandary (d. 1773), rabbi and dayyan in Constantinople, signed documents and halakhic decisions along with the other rabbis of the community from 1746 to 1764. He later became chief rabbi. His two sons, who also served as rabbis in Constantinople, were Raphael hezekiah h ayyim and abraham.

fernand alfandary (1837-1910), a judge, was appointed to the Court de Cassation in Paris (1894).

ALFANDARI, AARON BEN MOSES

(1690?-1774), rabbi and author. He taught at the yeshivah of Smyrna, where he served as dayyan. About 1757 he settled in Hebron where he was appointed chief rabbi. He wrote Yad Aharon, an attempt to bring Hayyim *Benveniste’s Keneset ha-Gedolah up to date by including later decisions as well as sources not available to Benveniste. He also added his own decisions, as well as a work on the methodology of the Talmud. The volume on Orah Hayyim was published in Smyrna in 1735; on Even ha-Ezer in two volumes in 1756-66. The one to Yoreh Deah and the uncompleted manuscript on Hoshen Mishpat were destroyed in the great Smyrna fire of 1743. He also wrote Mirkevet ha-Mishneh, a commentary on Maimonides’ Yad Hazakah; most of it was destroyed in the same fire and only the first part was published (1755).

ALFANDARI, HAYYIM BEN ISAAC RAPHAEL

(c. 16601733), kabbalist and rabbi. He lived at Brusa, Turkey, where in 1681 he met Abraham Miguel *Cardozo [Cardoso]. According to the latter’s testimony, Alfandari later came to him in Constantinople for esoteric study and believed in Cardoso’s concept of the Divinity. For this reason Alfandari quarreled with Samuel *Primo, the rabbi of the Adrianople community. He was summoned before the scholars of Constantinople (c. 1683) and warned to disassociate himself from Cardoso’s circle. On this occasion he denied belonging to Cardoso’s circle and accused the latter of belief in the Trinity. Later Alfandari became an extreme Shabbatean. He signed his name "H ayyim Z evi," called himself "Messiah," and gathered a group of followers in Constantinople. Cardoso accused them of desecrating the Sabbath and eating forbidden food. In 1696 Alfandari settled in Jerusalem as head of the community (resh mata). He was active in public affairs and presided over a yeshivah. At one time he resided in Egypt, where he studied Isaac *Luria’s writings which were in the possession of Moses Vital, grandson of H ayyim *Vital. He also lived in Safed, where he wrote a booklet called Kedusha de-Vei Shimshei (printed in J. Kasabi’s Rav Yosef). By 1710 he had returned to Constantinople where, in 1714, he was a signatory to the excommunication of Nehe-miah *Hayon during the controversy on Oz le-Elohim (1713). In 1717, however, Alfandari was H ayon’s envoy and delivered letters of the scholars of Hebron and Salonika to the rabbis of Constantinople, and in 1718 he tried to reconcile H ayon with Naphtali *Katz. In 1722 his name appeared first on the list of the Safed scholars confirming Daniel Kapsuto’s credentials as emissary. He returned to Constantinople, and died there. He wrote Esh Dat (1718), homilies on the Torah, and at the end of that work, Muzzal me-Esh by his uncle Jacob; and Maggid me-Reshit, a collection of responsa by his grandfather Hayyim the Elder, which closes with Derekh ha-Kodesh (1710). Alfandari’s kabbalistic works have not survived.