ALCONSTANTINI

Family of Jewish courtiers in 13th-century Aragon probably originating from Constantine, North Africa. Nahmanides refers to them disapprovingly as "the Ishmael-ites of the court." Many members of the family were hated by the ordinary Jews for their arrogance and lack of sensitivity to the social problems of their community. The first members to attain importance were the brothers bah ya (Bahi’el, Bafi’el) and solomon of Saragossa. By 1229 the two brothers were already in receipt of crown grants from James 1 of Aragon – the revenues from the local dyeing vats and two pounds of mutton daily from the Jewish slaughterhouse. In the same year Bahya, who was Arabic interpreter to the court, was sent to Majorca with the count of Roussillon to conduct negotiations for the surrender of the Muslims. Bahya also took part in Jewish communal affairs and in 1232 signed the counterban against the group who had banned the study of *Maimonides. The overweening ambitions of the two brothers to attain the position of supreme judicial authority (dayyan) in Aragonese Jewry were frustrated by Judah de la Cavalleria, the royal baile. *Nahmanides also opposed the claims of the family to have one of its members appointed as rabbi and judge of Aragonese Jewry. However, Bahya continued his diplomatic activities. During the distribution of the lands of the conquered territories in the 1260s he received grants of large estates. In 1240 Solomon held a village and fortress near Tarragona and the revenues from some Catalonian knights.

Of Bahya’s two sons, moses and solomon, the former was by far the more active and important. The two brothers appear in the sources from 1264. Moses was appointed baile of Saragossa from 1276 until the end of 1278; he succeeded the late Judah de la Cavalleria, of a family that was Alcon-stantini’s staunchest opponent. As baile of Saragossa he was much involved in the collection of the salt tax in Aragon. In the years 1280-81 Moses was the baile of the city of Valencia. Even before his campaign for the conquest of Sicily had begun, Pedro ill gave in to the growing anti-Jewish pressure of the clergy and the nobility. Moses was the last Jew in the royal service to be dismissed from office. He was thrown into prison and brought to trial, in which he almost lost his life. The trial was the result of unpaid debts which he incurred during his work for the king. He was greatly disliked by Jews and Christians for his unscrupulous conduct.

Moses was also deeply involved in the affairs of the Jewish community. Members of the Alconstantini family were at constant odds with the community and its leading members, first and foremost Judah de la Cavalleria. Solomon Alconstantini was appointed one of the three magistrates (berurim) of the Saragossa community in 1271. Moses was implicated, with Meir b. Eleazar, in beating up R. *Yom Tov Ishbili for having delivered a legal opinion to the royal clerk on the feuds of the local great families.

The Alconstantini family was still aspiring to the office of chief justice and "crown rabbi" of the kingdom in 1294, and the queen of Castile applied to James ii of Aragon with the request that Solomon Alconstantini be confirmed in this office. James, however, refused, on the ground that the privileges granted to the family had lapsed during the reigns of his predecessors: "for great damage and destruction has been suffered by all the Jews in our kingdom, and it would be unreasonable that for the sake of one Jew we should thereby lose all the others."

In the 14th century the Alconstantini family declined from its former eminence. Some physicians of this name are mentioned as living in Aragon. solomon (early 14th century), probably a descendant of the family, was the author of Megalleh Amukot. Enoch B. Solomon *Al-Constantini was the author of philosophical works. An Alconstantini represented the *Huesca community in the disputation of *Tortosa (1413-14). After the expulsion from Spain, members of the Alconstantini family are found in Turkey. Later, they moved to Ancona, where the name assumed the Italian form, Con-stantini. Some of them were rabbis and community leaders in Ancona during the 17th and 18th centuries. When the French conquered Ancona (1797) sansone was one of the three Jews elected to the city council.

ALCONSTANTINI, ENOCH BEN SOLOMON

(c. 1370), physician and philosopher. His work Mar’ot Elohim ("Divine Visions") is extant in almost 30 manuscripts (described in the edition by C. Sirat in Eshel Beer-Sheva (1976), 120-99).

The book is divided into three topics, preceded by an introduction. The first topic interprets Isaiah 1:1-6; the second Ezekiel 1:1-20; the third, Zechariah 10. The exegesis is entirely philosophical and deals with the separate intelligences, the spheres, and the human intellect. Al-Constantini was influenced by Maimonides, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Averroes, Samuel ibn Tibbon, Moses of Narbonne, Levi b. Abraham, and Solomon ibn Gabirol (in the abridged version of Gabi-rol’s Mekor Hayyim, the Likkutim by Shem Tov ibn Falquera). A Bodleian manuscript (Opp. 585) of Al-Constantini’s work contains glosses by Menahem Kara.

JOSEPH

(14th century), Moroccan theological scholar. For unknown reasons he was put in prison where he wrote Aron ha-Edut ("Ark of Testimony") on such subjects as Maaseh Bereshit and Maaseh Merkavah, the story of the Garden of Eden, providence, prophecy, and Satan’s dispute with God (Job, chs. 1 and 2).

Manuscripts of the work are preserved in several libraries; one has been annotated by Moses *H agiz. In Saadiah b. Maimun *Ibn Danan’s Maamar al Seder ha-Dorot, Alcorsono is mentioned as an astrologer (Z.H. Edelman (ed.), Hemdah Genu-zah, (1855), 30).

ALCOTT, AMY

(1956- ), professional golfer, member of the lpga and World Golf Hall of Fame. Born in Kansas City, Missouri, Alcott grew up in Los Angeles, where she began playing golf as an eight year old putting toward sprinkler heads. She won the United States Golf Association juniors championship in 1973, two years before joining the Ladies Professional Golf Association (lpga) shortly after her 19th birthday. Alcott proceeded to win the third professional tournament she entered, the 1975 Orange Blossom Classic, which set a record for the fastest career win, and was subsequently named the tour’s rookie of the year. She went on to win 29 professional tournaments, including five majors: the Peter Jackson Classic in 1979, the U.S. Women’s Open in 1980, and the Nabisco Dinah Shore in 1983, 1988, and 1991. Alcott set a one-round tournament record of 65 when she won the 1984 Lady Keystone Open and tied the tour record of winning at least one tournament in 12 straight years. She shot her fifth career hole-in-one in 2001. Alcott was named Golf Magazine’s Player of the Year in 1980 and was awarded the lpga’s Founders Cup in 1986, designed to recognize altruistic contributions to the betterment of society by a member. She wrote Guide to Women’s Golf (1991) and produced the instruction video Winning at Golf with Amy Alcott (1991).

°ALCUIN

(Albinus Flaccus; c. 735-804), educator and tutor of Charlemagne from 781. Born in York, he was educated in a school where one of his teachers had been a student of Bede. Author of several books and educational manuals, Alcuin’s ex-egetical works make frequent reference to commentaries on scripture by Jewish scholars; his knowledge of them derives from the works of *Jerome. He was present at a religious disputation between a Christian scholar and a Jew in Pavia, Italy, held between 750 and 760.

ALDABI, MEIR BEN ISAAC

(c. 1310-c. 1360), religious philosopher, with strong leanings toward the Kabbalah. Aldabi was a grandson of *Asher b. Jehiel. As a young man he received a comprehensive education in biblical and rabbinic literature, and afterward he turned to philosophical and scientific studies. In 1348 he apparently left his native Toledo and settled in Jerusalem, where, in 1360, he finished his long contemplated work, Shevilei Emunah ("Paths of Faith"). It was first published in Riva di Trento, 1518.

Aldabi was moved to write his book by the belief, prevalent in the Middle Ages, that the Greek philosophers (especially Plato and Aristotle) derived the essentials of their knowledge from Jewish sources. He determined to assemble the fragments of ancient Jewish wisdom scattered throughout the various works of the philosophers and natural scientists and to trace them back to their original sources. Actually, as stated in the introduction, the book is merely a compilation of subjects and theories, some of them translated by him from foreign languages, and culled from different works. The various subjects are not arranged systematically but are presented in random sequence. He borrowed mainly from Hebrew literature and to some extent, particularly in the fields of medicine and astronomy, from Arabic literature. His philosophy is based largely on that of *Maimonides, his ethics on that of *Bahya b. Joseph ibn Paquda, and his theology on that of *Nahmanides and his circle. The influence of the last is particularly evident in Aldabi’s predilection for Kabbalah which he ties in with his rationalist philosophy. He relies on the encyclopedic Shaar ha-Shamayim of his predecessor Gershon b. Solomon of Ar-les, and for his psychological theories he uses the views of Joseph ibn *Z addik and *Hillel b. Samuel of Verona. Aldabi’s book is divided into ten "paths" (netivot) in which he treats (1) the existence and unity of God, His names, and divine attributes both from a philosophic and a kabbalistic point of view; (2) the creation of the world, geography and astronomy, and the elements; (3) the creation of man and family life (part of this section is taken, without acknowledgment, from the Iggeret ha-Kodesh of Nahmanides); (4) embryology, anatomy, and human physiology (a digest of the accepted theories on anatomy and physiology in medieval medicine, presented on the basis of the comparison between the microcosm and macrocosm); (5) rules for physical and "spiritual" hygiene (on the nature of anger, joy, and the like); (6) the nature and the faculties of the soul; (7) religious observances as defined by the Torah and rabbinic tradition; (8) the uninterrupted chain of the Oral Law from Moses to the Talmud; (9) reward and punishment and metempsychosis; and finally (10) the redemption of Israel, resurrection, and the world to come.

The last two topics are based largely on the opinions of Nahmanides and Solomon b. Abraham *Adret.

ALDANOV, MARK

(pseudonym of Mark Aleksandrovich Landau; 1889-1957), Russian novelist. Aldanov was born in Kiev and trained as a chemist and lawyer. He left Russia in 1919 and settled in France. During World War 11 he lived in the United States, but eventually returned to Europe and died in Nice. A writer of exceptional erudition and sophistication, Aldanov excelled in the historical novel – a genre in which he had few peers in Russian literature. He also wrote other prose works including several treatises on the philosophy of history. He is best remembered for his tetralogy Myslitel ("The Thinker"), a work set in Russia and Western Europe during the Napoleonic era. Aldanov’s novel Desyataya simfoniya (1931; The Tenth Symphony, 1948) is based on the life of Beethoven; and Nachalo kontsa (1936-42; The Fifth Seal, 1943) depicts Europe on the eve of World War 11. Aldanov was singularly successful in blending historical and fictitious characters and events, but unlike so many other Russian novelists – especially Tolstoy in War and Peace – he erected his historical scaffolding merely as a support for the fictional structure. This did not, however, discourage his tendency to devote more time to historical research than to pruning his own work. Aldanov also differed from Tolstoy in believing that the fate of men and nations was shaped not by laws but by historical accident. His writing shows a partiality for paradox and a fondness for a pose of ironic detachment. His novels were translated into many languages but, unlike those of some of his emigre colleagues, were unobtainable in the U.S.S.R. A staunch anti-Communist, Aldanov remained a liberal Russian intellectual, retaining only tenuous links with his Jewish heritage.

ALDEMA, GIL

(1928- ), Israeli musician and composer. Aldema’s father, Abraham Eisenstein (Aldema), was active in the early Israeli satirical theater. Gil Aldema studied piano and violin. Among his teachers were Menashe Rabina and Paul *Ben-Haim. During his army service he was wounded. Later he studied at the Jerusalem Music Academy and directed folk singing activities. In 1952 he became a music teacher and composed his early songs. In 1957 he went to the U.S. to study music and worked as a music arranger for the Carmon Dance Company. From the 1960s to the 1980s he worked at Kol Israel (Israel Broadcasting Authority) as a musical director of light music. Aldema is known for his work and arrangements for choirs such as Rinat, Cameran, and others. He composed many songs, such as "Ana Halakh Dodekh," "Ashirah li-Yedi-day," "Zemer Ikkarim," "Maliol Dayyagim," and more, which were published in Ziyyunei ha-Derekh (1979), Mahberet Meza-meret (1981), Shir le-Elef Arisot (1983), and Menifah Kolit (2000). Among his awards are the akum Prize for his contribution to Israeli folk music (1984) and the Israel Prize for Israeli folk songs (2004).

ALDERMAN, GEOFFREY

(1944- ), British historian. An Oxford graduate, Geoffrey Alderman was professor of politics and contemporary history at Middlesex University in London and later vice president of American Intercontinental University in London. One of the best-known historians of the Jewish community in Britain, Alderman is the author of Modern British Jewry (1992), a sophisticated and deeply researched history of the Anglo-Jewish community since 1858; The Jewish Community in British Politics (1983); London Jewry and London Politics, 1889-1986 (1989); a history of the right-wing Orthodox, Federation of Synagogues, 1887-1987 (1987); and other works. In recent years he has written an often controversial weekly column in the Jewish Chronicle newspaper, which generally reflects his Orthodox Zionist viewpoint.

°ALDO MANUZIO

(1449-1515). Italian humanist, Hebraist, and printer. In 1494 he set up a printing press in Venice which soon became famous. Printing Greek and Latin grammatical works, he appended to several of them the first printed Hebrew grammar for Christian students (lntroductio perbrevis in linguam hebraicam, date of foreword 1501). This was reprinted separately eight times by Aldo himself under a slightly different title (a facsimile reprint was published in 1927). Aldo also printed Leone Ebreo’s (Judah *Abrabanel) Dialoghi di Amore (1544, 1545) calling him a convert to Christianity. The type is very similar to that used by Gershom *Soncino. This led to a rather acrimonious competition between the two great printers.

ALDRICH, ROBERT

(1918-1983), U.S. director, producer. Born in Cranston, Rhode Island, to a prominent East Coast family, Aldrich departed from family tradition to become one of Hollywood’s most provocative filmmakers. After attending the University of Virginia, where he played football and studied economics, Aldrich began his film career as a production clerk for rko at the onset of wwii. Aldrich quickly became an assistant director and spent the rest of the decade learning from esteemed directors such as Lewis Milestone, Joseph Losey, Abraham Polonsky, and Charlie Chaplin. Aldrich made his directorial feature film debut in 1953 with The Big Leaguer. The following year, he made his directorial breakthrough with the western Apache featuring Burt Lancaster as a pacifist Native American warrior in a film that presaged Aldrich’s career-long exploration of violence and morality. Aldrich solidified his reputation as a director with Vera Cruz (1954), another western starring Lancaster, this time opposite Gary Cooper, as the two men vied for gold in Mexico. Aldrich’s distinctive style continued to crystallize in two provocative film-noir features, Kiss Me Deadly (1955) and The Big Knife (1955), both of which earned him critical acclaim in Europe. After a series of disappointing films in the late 1950s, Aldrich rejuvenated his career with What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), for which Bette Davis won the Academy Award for Best Actress. Aldrich’s turbulent career was marked by two more highlights, The Dirty Dozen, the highest grossing film of 1967, and the popular prison film The Longest Yard (1974), starring Burt Reynolds. Aldrich served as president of the Director’s Guild of America from 1975 to 1979, during which he successfully lobbied for increased creative authority for directors.

ALDROPHE, ALFRED PHILIBERT

(1834-1895), French architect. Born in Paris, Aldrophe designed the French buildings at the international exhibitions (1855, 1867). He designed the synagogues in the Rue de la Victoire and at Versailles. He also built private homes in Paris including that of Baron Gus-tave de *Rothschild. He erected several important monuments in the Pere-Lachaise cemetery.

ALDUBI, ABRAHAM BEN MOSES BEN ISMAIL

(14th century), Spanish talmudist. Aldubi studied under Solomon b. Abraham *Adret and was the teacher of *Jeroham b. Me-shullam. The whole of his Seder Avodah bi-Kezaarah, dealing with the Day of Atonement service in the Temple, was incorporated by Jeroham in his Toledot Adam ve-Havvah. Aldubi’s book Hiddushim ve-Shitah to Bava Batra is mentioned in the responsa of Moses b. Isaac Alashkar (1554), and one of his re-sponsa is printed in the Zikhron Yehudah (1846) of Judah the son of *Asher b. Jehiel.

ALECHINSKY, PIERRE

(1927- ), Belgian painter. Ale-chinsky was leader of the CoBrA group of artists, formed in Brussels, which fostered a spontaneous approach to painting and opposed social realism on the one hand and a calculated abstraction on the other. Alechinsky’s works have been described as "explosive." They are characterized by a sense of perpetual movement and flux in which incomplete forms appear and dissolve. Alechinsky studied at the Ecole Nationale dArchitecture et des Arts Decoratifs in Brussels. In 1951 he moved to Paris, joining other members of the CoBrA group. Later he visited Japan, where he made a film on Japanese calligraphy. Alechinsky exhibited at the Venice and Sao Paulo Biennales.

ALEF

(Heb![]() , first letter of the Hebrew alphabet; its numerical value is 1. It is a plosive laryngal consonant, pronounced according to the vowel it carries. The earliest clear representation of the ‘alef is to be found in the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions of c. 1500 B.c.E. This acrophonic pictograph of an ox-head (alp) ir develops through the Proto-Arabic ft and South Arabic A into the Ethiopic A on the one hand, and through the Proto-Canaanite and into the tenth-ninth centuries b.c.e. classical Phoenician alef-t on the other hand. The Ugaritic consonantal cuneiform script of the 14th century b.c.e. has three alef signs: «->- (a), (5i), and JH (u). About 800 b.c.e. the Greeks borrowed the Phoenician alef and used it as a vowel (alpha). They altered its stance and turned it into A, a shape which was adopted by Latin, among other scripts. While the Phoenician ‘alef underwent its own evolution fifth century b.c.e., ^ – Punic, Neo-Punic), the Hebrew and the Aramaic scripts, which derived from Phoenician, developed it as follows: in seventh century b.c.e. Hebrew, along with the cursive forms f and "f® there existed a formal one. The latter is the ancestor of the first letters of many alphabets which developed from the third century b.c.e. onward. They include: Nabatean: The last form, which occurs in the first century c.e. documents found near the Dead Sea, indicates the date when the Arabic ‘alif was fixed. The Palmyrene M turned into the Syriac re* (Estrangela), but in other Syriac systems it is a vertical stroke resembling the Arabic. The Jewish (square Hebrew) ‘alef preserved the shape of its Aramaic ancestor. Although there is a tendency to curve the left leg – as in Nabatean and Palmyrene, e.g., the Nash Papyrus – the straight-legged ‘alefK prevails. The Jewish cursive forms of the time of the Herodian dynasty < r disappeared apparently after the period of Bar Kokhba. The Jewish formal ‘alef did not change its basic shape during the following period. In the cursive styles of the various Jewish local systems the left leg became the main stroke – A; so it is in the Ashkenazic cursive from which stems the modern cursive ‘alefH, It. See ^Alphabet, Hebrew.

, first letter of the Hebrew alphabet; its numerical value is 1. It is a plosive laryngal consonant, pronounced according to the vowel it carries. The earliest clear representation of the ‘alef is to be found in the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions of c. 1500 B.c.E. This acrophonic pictograph of an ox-head (alp) ir develops through the Proto-Arabic ft and South Arabic A into the Ethiopic A on the one hand, and through the Proto-Canaanite and into the tenth-ninth centuries b.c.e. classical Phoenician alef-t on the other hand. The Ugaritic consonantal cuneiform script of the 14th century b.c.e. has three alef signs: «->- (a), (5i), and JH (u). About 800 b.c.e. the Greeks borrowed the Phoenician alef and used it as a vowel (alpha). They altered its stance and turned it into A, a shape which was adopted by Latin, among other scripts. While the Phoenician ‘alef underwent its own evolution fifth century b.c.e., ^ – Punic, Neo-Punic), the Hebrew and the Aramaic scripts, which derived from Phoenician, developed it as follows: in seventh century b.c.e. Hebrew, along with the cursive forms f and "f® there existed a formal one. The latter is the ancestor of the first letters of many alphabets which developed from the third century b.c.e. onward. They include: Nabatean: The last form, which occurs in the first century c.e. documents found near the Dead Sea, indicates the date when the Arabic ‘alif was fixed. The Palmyrene M turned into the Syriac re* (Estrangela), but in other Syriac systems it is a vertical stroke resembling the Arabic. The Jewish (square Hebrew) ‘alef preserved the shape of its Aramaic ancestor. Although there is a tendency to curve the left leg – as in Nabatean and Palmyrene, e.g., the Nash Papyrus – the straight-legged ‘alefK prevails. The Jewish cursive forms of the time of the Herodian dynasty < r disappeared apparently after the period of Bar Kokhba. The Jewish formal ‘alef did not change its basic shape during the following period. In the cursive styles of the various Jewish local systems the left leg became the main stroke – A; so it is in the Ashkenazic cursive from which stems the modern cursive ‘alefH, It. See ^Alphabet, Hebrew.

Alef in Aggadah and Folklore

The alef is more personified than any of the other Hebrew letters. Praised is its humility, which is reflected in the fact that it did not ask God to be the means of creation nor that the Bible be started with it (the Bible begins with the second letter of the alphabet bet). The alef was rewarded by starting the Decalogue (’3′IX, Anokhi; "I") and by denoting the highest number, ^Vx (elef, "thousand"). The three letters (^ ,X) which constitute the alef have been interpreted according to different homiletic means such as the *notarikon HS nriSX (eftah leshon peh; "I shall open the tongue (and) mouth") which is the opening phrase of God’s proclamation: "I shall open the tongue (and) mouth of all people to praise Me, or to study, and teach" (Midrash Alfa Beta de-Rabbi Akiva in A. Jellinek, Beit ha-Midrash, 3 (19382), 12-14; cf. the use of the root ^Vx in Job 33:33). Since alef is the initial letter of God’s name at the time of Creation (D’liVx, Elohim in Gen. 1:1) and of the three words alluding to His Ineffable Name (n’HX ItCtt n’HX in Ex. 3:14), it is fundamental in Hebrew inscriptions in *amulets and letter magic. Similarly, the letter ‘A" is to be found at the end of the European magic-formulistic inscriptions belonging to the "abracadabra" type. The expression "from alef to tav" (Shab. 55a and Av. Zar 4a) corresponding to that of "Alpha and Omega" (Rev. 1:8 and 22:13) denotes complete integration.

"It is our duty

ALEGRE, ABRAHAM BEN SOLOMON

(1560-1652), rabbi and scholar of Constantinople. H ayyim *Alfandari in his Maggid me-Reshit records Alegre’s controversy on a halakhic issue (responsa 4, 5). His own responsa were published together with those of Jacob Shalem Ashkenazi (Sephardi emissary of Jerusalem), in Salonika in 1793. Alegre is more widely known by the title of his extensive commentary on Maimo-nides’ Sefer ha-Mitzvot, Lev Same’ah, (Constantinople, 1652), printed in the Israeli edition of the Mishneh Torah (vol. 1, 1962). In this work, which took 40 years to complete, Alegre analyzes the 14 principles defined by Maimonides in the introduction to his Sefer ha-Mitzvot and those on which he based the enumeration and classification of the mitzvot. He particularly justifies Maimonides against the strictures of Nah-manides on the Sefer ha-Mitzvot. His son-in-law, Levi Teglio, in a foreword to the Lev Same’ah. states that Alegre wrote a homiletical work and a book of responsa.

ALEINU LE-SHABBE’AH

(Heb![]() to praise [the Lord of all things]"), prayer now recited at the conclusion of the statutory services. Originally it introduced the *Malkhuyyot section of the Rosh Ha-Shanah additional service in which the kingship of God is proclaimed and where it is recited with great solemnity. Its theological importance secured for it, from the 12th century at least, a special place in the daily order of service (Malizor Vitry, p. 75); first at the conclusion of the morning service and later at the end of the other two daily services as well (Kol Bo, no. 16). As with some other prayers, it was taken over from the New Year liturgy into the additional service of the Day of Atonement.

to praise [the Lord of all things]"), prayer now recited at the conclusion of the statutory services. Originally it introduced the *Malkhuyyot section of the Rosh Ha-Shanah additional service in which the kingship of God is proclaimed and where it is recited with great solemnity. Its theological importance secured for it, from the 12th century at least, a special place in the daily order of service (Malizor Vitry, p. 75); first at the conclusion of the morning service and later at the end of the other two daily services as well (Kol Bo, no. 16). As with some other prayers, it was taken over from the New Year liturgy into the additional service of the Day of Atonement.

The style of Aleinu is that of the early piyyut, composed of short lines, each comprising about four words, with a marked rhythm and parallelism. It is one of the most sublime of Jewish prayers, written in exalted language.

It is referred to as Tekiata de-Vei Rav ("The Shofar Service of *Rav") and it has therefore been ascribed to this third-century Babylonian teacher (tj rh 1:3, 57a; cf. Av. Zar. 1:2, 39c). But the Aleinu may be considerably older. According to one popular tradition, it was composed by Joshua (Arugat ha-Bosem, ed. by E.E. Urbach, 3 (1962), 468-71); according to another, it was written by the Men of the Great Assembly during the period of the Second Temple (Manasseh Ben Israel, Vindiciae, vol. 4, p. 2). There are good reasons for placing it within that period, because there is no mention of the Temple restoration in the prayer while there is reference in it to the Temple practice of prostration. Prostration during Aleinu is still customary in the Ashkenazi rite in most communities on Rosh Ha-Shanah and on the Day of Atonement, while in the other services the congregants bow when reciting the words "we bend the knee…." The description of God as the "King of the kings of kings" may be due to Persian influence, since the Persians described their king as "the king of kings" (cf. Dan. 2:37). It has been suggested that the prayer has its origin in early *Merkabah mysticism; a version of Aleinu was recently found among hymns used by the early mystics (see bibliography).

Contents

The main theme of the prayer is the kingdom of God. In the first part, God is praised for having singled out the people of Israel from other nations, for Israel worships the One God while others worship idols. The second paragraph expresses the fervent hope for the coming of the kingdom of God, and the universal ideal of a united mankind which will recognize the only true God, and of "a world perfected under the kingship of the Almighty." The juxtaposition of the two paragraphs provides a coherent theology connecting the idea of a chosen people (Israel) with the challenge that such distinctiveness has for its purpose, religious union and the perfection of mankind under the kingdom of God.

Censorship

In the Middle Ages the prayer was censored by Christians as containing an implied insult to Christianity. They claimed that the verse "for they prostrate themselves before vanity and emptiness and pray to a God that saveth not" was a reference to Jesus. Pesah Peter, a 14th-century Bohemian apostate, spitefully alleged a connection between the numerical value of the Hebrew word p’"]! (va-rik; "and emptiness") and (Yeshu; the name of Christ). The elder *Buxtorf (16th century) and *Eisenmenger (17th century) and others repeated the charge; and Jewish apologists from Lippmann Muelhausen (15th century) to Manasseh Ben Israel and Moses Mendelssohn were at pains to refute it. However, the 13th-century Aru-gat ha-Bosem by Abraham b. Azriel does mention a tradition that the numerical value of p’TH Varf? (la-hevel va-rik; "vanity and emptiness") equals IHnHl (Yeshu u-Muhammad; Jesus and Muhammad). Some ecclesiastical censors also deleted the previous passage: "Who did not make our portion like theirs, nor our lot like that of all their multitude." Eisenmenger refers to the custom of spitting at the offending word which he interprets as an additional insult to Christianity. This was, no doubt, a popular gesture suggested by the double meaning of rik ("emptiness" and "spittle"). In view of this accusation, rabbis such as Isaiah Horowitz discouraged the indecorous practice. (The popular Yiddish phrase, er kummt tsum oysshpayen ("he comes at the spitting") came, therefore, to describe someone who arrived at a service as late as the concluding Aleinu.) The censors remained adamant even when it was pointed out that the offending phrase is found in Isaiah (30:7; 45:20), that the Aleinu prayer is probably pre-Christian, and that if Rav was the author, it was composed in a non-Christian country. The line had to be removed from Ashkenazi prayer books. In 1703 its recital was prohibited in Prussia. The edict, which provided for police enforcement, was renewed in 1716 and 1750. Even earlier, some communities omitted or changed the offending lines as an act of self-censorship (e.g., by replacing she-hem, "for they [prostrate themselves before vanity]," with she-hayu, "for they used to.."). The Sephardim – especially in Oriental countries – retained the full text and it has now been restored to some prayer books of the Ashkenazi rite as well.

The Blois Tragedy

*Ephraim of Bonn tells how the Jews of *Blois, martyred in 1171, went to their death chanting Aleinu to a soul-stirring melody which "at the outset. was subdued, but at the close was mighty." The messianic theme of the second paragraph would have made it especially significant for the Jew in the tragic moments of his history, and it takes its place with the Shema as a declaration of faith. Its introduction into the daily service may have been an act of defiance when Christian pressure was on the increase.

Reform Usage

In the Reform liturgy the prayer, with some modifications, has retained its importance and is called the "Adoration." The Ark is opened and the congregation bows as the words "we bow and prostrate ourselves" are recited.

Music

The Aleinu of the *Musaf prayer of the Penitential Feasts is notable, in Ashkenazi tradition, for its music; the Sephardi and eastern communities sing it to one of their regular prayer modes. A musical peculiarity was claimed for the Ashkenazi tune as early as 1171, when it was sung by the martyrs of Blois (Neubauer-Stern, p. 68, 202). Its written tradition, however, dates from the 18th and 19th centuries. The Ashkenazi Aleinu belongs to the class of unchangeable *Mi-Sinai tunes. Thus, it cannot be traced back to a definite archetype, but only to a basic concept or musical idea which is executed differently in every performance.

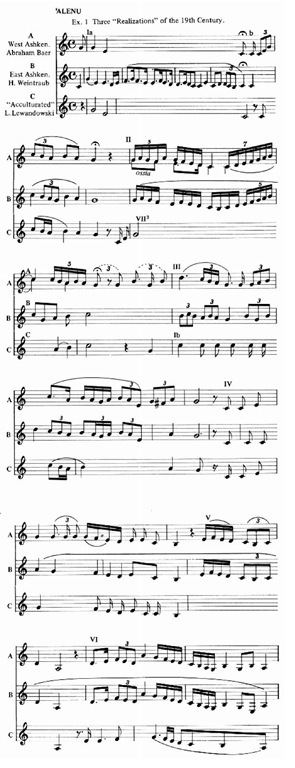

The Aleinu tune consists of seven melodic sentences or "themes" (see Music Example), always produced in the same order. Four of them, nos. 1, iv, v, and vi, are virtually invariable in outline; the others, especially the final themes iii and vii, are frequently changed. The Aleinu has several themes in common with other Mi-Sinai tunes: iv, v, vi, and vii3 recur, in the same order, in the Avot Benediction; ii, v, and vii2 are known from the *Kol Nidrei. Apart from mere ornamental elaboration and minor variants, three main patterns of melodic realization can be distinguished: (1) the predominant version (Examples ia and ib), known to both western and eastern Ashkenazi communities. This is well on the way to major tonality which gradually replaces the original mode (featuring a diminished seventh). Cantors from Russia often omitted some of the themes, except 1 and 5, replacing them by repetitions. This points to a western-Ashkenazi origin for the tune. (2) "Acculturated" versions (such as Example ic) came into being in the mid-i9th century. They feature drastic reduction of coloraturas and decided major tonality. (3) A presently obsolete, expanded version was current in the 18th and early 19th century. It is excessively ornate, and may be regarded as a cantorial development of or a "fantasia" on the traditional tune. Many of its extended vocalizations and trumpet flourishes represent a musical illustration of certain mystical intentions (kavvanot) connected with the prayer. An old theory proposes a relationship between the tune of Aleinu and the Sanctus of the Roman Mass ix. Since the latter, however, is not dated earlier than the 14th century, no conclusions can be drawn from the slight similarity between the two tunes.

°ALEKSANDER JAGIELLONCZYK

(1461-1506), grand duke of Lithuania 1492-1501, king of Poland 1501-06. In 1495 Aleksander expelled the Jews from Lithuania. The young prince may also have been indoctrinated by his rabidly anti-Jewish mentor Jan *Dlugosz. Aleksander would also have found it convenient to confiscate the property of the exiles to finance his wars against Russia. When elected king of Poland, however, Aleksander’s attitude toward the Jews was more tolerant. In 1503 he allowed the exiled Lithuanian Jews to return. The Polish code, compiled by his chancellor Jan Laski (1506), includes the former grants of privileges accorded to Polish Jewry, but with the preamble that their incorporation is "to protect the citizenry from the Jews."

ALEKSANDRIYA

Small town in Rovno district, Volhynia, Ukraine. The Jews settled there before the *Chmielnicki uprising (1648-50) and suffered at the hands of the Cossacks. Few Jews lived there until 1700, when they were obliged to pay a 350-zloty head tax. The community grew rapidly in the 19th century. In 1847 it numbered 728 and in 1897, 2,154 (out of a total population of 3,189). Jews built a sugar refinery, textile factories, and a sawmill, and rented flour mills from Count Lubomirski. The community maintained a school, a club, and a Hebrew library. The Zionist movement was very popular there. The Hebrew Tarbut school founded in 1917 served as a model for most of the towns of Volhynia. The Jewish population numbered 1,700 in 1939. During Soviet rule in 1939-41 all Jewish political parties, organizations, and cultural institutions were closed and the economy was nationalized. The Germans occupied Aleksandriya on June 29, 1941, and in the following days pillaged Jewish property and burned down the synagogues with the help of local peasants. On July 31, 85 Jews were executed. On September 22, 1942 about 1,000 Jews, including women, children, and the aged, were taken to the forest at Swiaty and murdered. Fifty Jews returned to the town after the war but soon left for Palestine.

ALEKSANDRIYA

(originally Becha), town in Kirovograd district, Ukraine. The first Jews settled in Aleksandriya at the end of the 18th century. In 1864 they numbered 2,474, and in 1897, 3,735 (26% of the total population). In 1910 the community had five synagogues, a talmud torah and a communal school, and 11 hadarim with 230 pupils. The main occupation of the Jews in Aleksandriya was garment manufacturing. In a pogrom on April 23, 1882, Jewish shops and homes were pillaged. On the Day of Atonement of 1904 (September 6), three Jews were killed and several injured in a pogrom. During the civil war of 1919-20, the Jews in Aleksandriya endured great suffering, Aleksandriya being the headquarters of Ataman Grigoryev, leader of the Ukrainian pogrom bands. They were also attacked by Denikin’s "White" army. In 1926 the Jewish population in Aleksandriya numbered 4,595 (23% of the total). During the Soviet period most of the Jews worked as artisans in cooperatives. The central Chabad synagogue was still operating in the early 1930s. The Jewish population declined to 1,420 persons in 1939 (total population 19,755). Aleksandriya was occupied by the Germans on August 6, 1941. They murdered 463 males on September 19, and over 300 on August 29. In all, 2,572 were murdered, including Jews from the surrounding area.

ALEKSANDROW

(Danziger), influential dynasty of h asidic rabbis in Poland active from the second half of the 19th century (see *H asidism). Their "court" was at *Aleksandrow Lodzki (Yid. Alexander), a small town near Lodz. In contrast to the H asidim of Gora-Kalwaria (Yid. Ger), the Aleksand-row H asidim generally did not take part in Jewish party politics in Poland.

The founder of the dynasty, shraga feivel danziger (d. 1849) of Grojec (Yid. Gryce), was rabbi in the small towns of Sierpc, G^bin, and Makow; Shraga succeeded his rebbe, R. Isaac of Warka. His son, jehiel, the disciple of Isaac of Warka, settled in Aleksandrow and made it the seat of the "court." Jehiel’s son, jerahmeel israel isaac (1853-1910), was the outstanding member of the dynasty. He was learned in a wide variety of subjects and had a keen intellect, and was beloved by the H asidim. A natural leader, Jerahmeel would question his followers about their circumstances and advise them accordingly, consoling, encouraging, and reproving. He had a small circle of learned disciples, but also provided moral guidance to all his followers. He wrote Yismah Yisrael (1911). Jerahmeel’s brother and his successor was samuel zevi (d. 1925). The last rabbi of the line, isaac menahem (1880-1943), established a network of Aleksandrow yeshivot in various places. He perished in the concentration camp at *Treblinka. He wrote Ake-dat Yizhak (1953). After the war, judah moses tiehberg, Jehiel’s grandson, head of a yeshivah in Bene-Berak, was declared "Aleksandrow Rabbi" He wrote Kedushat Yizhak (1952) on the Aleksandrow dynasty.

ALEKSANDROW LODZKI

Town in central Poland, founded in 1818. The first Jewish residents were under the jurisdiction of the Lutomiersk kahal, but an independent community was established in 1830 by Jews who came from Lutomiersk. In 1826 the governor of the Polish Congress Kingdom granted the community a privilege permitting them to reside and acquire property in specified areas of the town. The Jewish population of Aleksandrow Lodzki numbered around 1,000 in the 1850s; 1,673 (27.9% of the total population) in 1879; 3,061 (24.1%) in 1909; and 2,635 (31.9%) in 1921.

Holocaust Period

In 1939 there were 3,500 Jews in Aleksandrow, comprising one-third of the total population. The German army occupied the town on Sept. 7, 1939, and on the following day set the main synagogue afire and forced the Jews to burn the Torah scrolls which were found in private homes. There were several cases of kiddush ha-Shem when Jews sacrificed their lives while trying to save the sacred books. Kidnapping of Jews in the streets, open robbery, and the imposition of ever higher ransoms continued until the end of 1939. In this period the famous "court" of the Aleksandrow zaddik (Danziger) was liquidated. All Jews of Aleksandrow were expelled to Glowno (in the Generalgou-vernement) on Dec. 27, 1939. Some of them remained there and the others were deported to other towns of the Gener-algouvernement. The Jewish cemetery of Aleksandrow was plowed up and turned into a park.

ALEMAN, MATEO

(1547-c. 1615), Spanish novelist of "New Christian" descent. He studied medicine at Salamanca and Alcala. Always poverty-stricken, he was several times imprisoned for debt. *Conversos were forbidden to leave Spain, but Aleman secured permission by means of a bribe and arrived in the New World in 1608. Aleman’s fame rests on one great work, the Guzman de Alfarache, the first part of which was published in 1599, the second in 1604. This is a picaresque novel marked by a skillful fusion of narrative and didactic elements. The picaresque genre was introduced in 1554 with an anonymous work called La vida de Lazarus de Tormes …. The bitterness expressed in the novel has been ascribed to its author’s position as a Converso, one of whose ancestors was burned in an auto-da-fe, while some have suggested that it may merely reflect Aleman’s personal disillusionment. In the novel Aleman contrasts the nobility that has possessions and power with the "ignobility" that lacks lineage and respectability. He died in Mexico.

ALEMANNO, JOHANAN BEN ISAAC

(1435/8-after 1504), philosopher, kabbalist and biblical exegete. A descendant of an Ashkenazi family expelled from France, his father married an Aragonese Jewess, and the family came to Italy because of his grandfather’s (Elijah) mission to the Pope.

Alemanno himself was born in Mantua and was reared in Florence in the house of Jehiel of *Pisa, where he acquired a thorough education in several disciplines, especially philosophy. Later he taught in various cities in Italy. At the age of 35 he settled in Mantua where he was among the guests of Luigi llI Gonzaga, and studied with R. Yehudah Messer Leon. In 1488 he returned to Florence, where he again stayed with the family of Jehiel of Pisa until they left Florence in 1497. In the house of this patron Alemanno spent some quiet years and was able to complete the works he had begun and to embark on new ones. The most important of these works are the following:

(1) Heshek Shelomo, a philosophical commentary on the Song of Songs, which Alemanno began at the age of 30. In 1488 he read portions of his manuscript to Giovanni *Pico della Mirandola who urged him to complete it. The work, thus far never printed in its entirety, is extant in manuscripts (Bodleian, 1535, British Museum 227, Ms. Moscow-Guensburg). A substantial part of Alemanno’s introduction to it was published by Jacob Baruch under the title Shaar ha-Heshek (Leghorn, 1790) in a very imperfect edition, which was reprinted in Halberstadt (c. 1862) without change. In addition, some fragments of the work were published in various places. The introduction constitutes almost half of the book, and opens with a lengthy section, Shir ha-Ma’alot li-Shelomo, glorifying King Solomon, as a philosopher, Kabbalist and magician. Ale-manno goes on to discuss the content, character, form, and significance of the Song of Songs. In his opinion, the book in its simple sense treats of earthly love, although allegorically Solomon sought to depict divine love.

(2) Einei ha-’Edah an unfinished philosophic-kabbalistic commentary on the Pentateuch still in manuscripts. The general line of thought resembles that of the Eleshek Shelomo.

(3) Hei ha-Olamim is Alemanno’s chief work, on which he labored from 1470 until 1503. One manuscript is found in the library of the Jewish community of Mantua, and another in the Jewish Theological Seminary (Rab. 1586). The work deals with the problem of how man may attain eternal life and rise to communion with God. The introduction prescribes a twofold method of instruction to be followed by every teacher: for the masses, a simple method readily understandable to all; and for the learned and informed, a logical one calculated to remove doubt. In this work Alemanno makes use of both methods. He introduces two characters, the Meliz Yosher al-Leshono ("the felicitous interpreter") who presents each subject in succinct and simple words; and the Dover Emet bi-Le-vavo ("one who speaks the truth in his heart") who engages in elaborate proofs. The author charts the career of the ideal man; he describes man’s physical life from conception to maturity and indicates the preparations one should undertake at every stage of his life to attain perfection. Then he discusses man’s spiritual development through the perfection of his moral and intellectual capacities. The final goal is the attainment of the perfect love of God and union with Him.

(4) Likkutim are various notes and reflections, among them, those of the years 1478 and 1504, which Alemanno had intended to later incorporate into his other work. It is extant in manuscript (Bodleian 2234). The material preserved in this compilation reflects the wide scope of his reading and his acquaintance with philosophical, Kabbalistic, magical and astrological traditions of Spanish extraction, and they serve as the main source of inspiration for his later works.

Alemanno often mentions a work of his entitled Ha-Meassef; perhaps the reference is to the Likkutim. (The name Likkutim was originally used by Abraham Joseph Solomon Graziano in the 17th century.) Alemanno presumably wrote annotations to the Hai ben Yoktan by Abu Bakr ibn Tufayl found in manuscript (Munich 59). Another work by Alemanno, Zeh Kol ha-Adam, is also occasionally mentioned; it is probably identical with Hlai ha-Olamim. In addition, he probably wrote Pekah Koah, which has been lost. The works Melekhet

Muskelet - a book of magic translated from Greek into Latin and extant only in some Hebrew fragments from the circle of Alemanno – and Peri Megadim have been erroneously ascribed to him. Alemanno was well-versed in Greek and Arabic-Jewish philosophy and familiar with the Latin literature of antiquity and the Middle Ages. His erudition and writings were held in such high regard in his day that a scholar such as Pico della Mirandola wished to become his student in Hebrew literature. The hypothesis that Alemanno was the same person as Dattilo or Mithridates, both of whom moved in the circle of Pico della Mirandola, is unfounded. Alemanno’s son Isaac was the teacher of Giovanni Francesco, the nephew of Pico della Mirandola. Alemanno influenced a series of Jewish Italian thinkers, more notably R. Isaac de Lattes and R. Abraham Yagel.

Alemanno was well-acquainted with Italian Jewish Kabbalah: mostly Abraham Abulafia’s prophetic Kabbalah, and Menahem Recanati’s writings, and he was part of a revival of interest in this lore evident among Jews and Christian in the Florentine Renaissance. He conceived magic as a high form of activity, even higher than Kabbalah, and described it as Hokhmah ruhanit, "the spiritual lore". He studied a number of Jewish and other type of magical books, like Sefer ha-Levanah and a Sefer Raziel translated from Latin, and resorted to astro-magic views, under the impact of the tradition of Abraham ibn Ezra and his many commentators in 14th-early 15th century Spain, whose writings he often quotes. This synthesis between Kabbalah and magic is evident also in Pico della Mirandola’s thought. The affinities between Alemanno’s thought and that of his Florentine Christian contemporaries still waits for detailed investigations. It is possible that Alemanno arrived in Jerusalem in 1522.

ALEPPO

(Ar. Halab; called by the Jews Aram-Zoba (Aram Z ova)), second-largest city in Syria and the center of northern Syria. The Hebrew form of Aleppo (H aleb) is, according to a legend quoted by the 12^-century traveler, *Pethahiah of Re-gensburg, derived from the tradition that Abraham pastured his sheep on the mountain of Aleppo and distributed their milk (halav) to the poor on its slopes. According to Jewish tradition, mentioned by Rabbi Abraham Dayyan, the beginning of the community was in the era of Joab ben Z eruiah, the conqueror of the city in the time of King David, who also built the great synagogue. There are also other non-Jewish traditions which confirm the existence of the community in the Greek period. It would seem that the establishment of the Jewish community was in this period. Jewish settlement there has continued uninterruptedly since Roman times. The ancient section of the great synagogue was built in the form of a basilica with three stoae during the Byzantine period; an inscription on it dates from 834. The Jews lived in a separate quarter before the Muslim conquest in 636. They lived separately during the Muslim period in the northeastern area of the city. The most ancient synagogue, named Kanisat Mu-takal, was built in the fourth century and was located in the Parafara quarter in the northeastern region of the city. It is the oldest Jewish building in the city. During the Muslim period the Jewish quarter was named Mahal al-Yahud. In the Seljuk period the Jewish quarter was spread over a large area of the walled city. On the south it bordered on the market street, on the west the castle, on the east the Dar Al-Bbatih food merchandise area, and on the north the wall and the Jewish gate (Bab al-Yahud). This latter gate was named from the end of the 12th century Bab al-Nasr (Victory Gate). In the anarchic period (1023-79) it seems that there were also Jews who lived outside the Jewish quarter. A document from the 12th century deals with a Jewish building in the market street. There was also a synagogue located in a new suburb outside the walls.

*Saadiah Gaon was in Aleppo in 921 and it is said that he found Jewish scholars there. In the 11th century learned rabbis led a well-ordered community. R. Baruch b. Isaac was its leader at the end of the 11th century: fragments of his commentary on the Gemara as well as responsa have been found in the genizah. Apparently the rosh kehillot ("head of communities"), i.e., a leader common to the various communities of Jews (such as Babylonians, Palestinians, etc.), represented all Jews before the Muslim authorities. The leader of the community of Aleppo during the years 1015-29 was Jacob ben Joseph, who came to Aleppo from Fustat and served there as dayyan. He was also the dayyan responsible for the other communities in the region and received the title rosh kala from the Babylonian academy. He also had in Aleppo a bet midrash and had students from various countries. His successor in the 1030s was Jacob ben Isaac, who served as the dayyan of the Aleppo community. He died c. 1036. His successor as dayyan was Tamim ben Toviah. His grandson Tamim ben Toviah is known from another document dated 1189. A famous rabbi of the community, Barukh ben Isaac, served as dayyan in Aleppo from the 1180s. In the 1190s he headed a bet midrash and students gathered there around his son Joseph. Rabbi Barukh gave the proselyte Obadiah, who came to his bet midrash, a recommendation to the Jewish communities. Rabbi Barukh was known also as a significant halakhic posek, and as a Talmud parshan, too, and his commentaries were cited by scholars from Aleppo. He was busy also in public affairs.

The community seems to have had close contacts with Palestine, and heads of Palestinian yeshivot visited Aleppo. In the second half of the 12th century the great yeshivah of Baghdad was in contact with Aleppo. R. Zechariah b. Bara-chel, a disciple of the gaon *Samuel b. Ali of Baghdad, was appointed to head Aleppo’s bet din. The scholars of Aleppo also exchanged letters with *Maimonides; R. *Joseph b. Aknin, Maimonides’ disciple, lived in Aleppo at that time. We identify this scholar with the leader of the community in the 12th century, Joseph b. Judah Ibn Simeon. This scholar was a merchant who traveled to India and other lands and later returned to Aleppo, bought a big estate outside the city, and founded on it a bet midrash. He was also the court physician of Al-Malik Al-Tahir. Maimonides wrote that the Jews of Aleppo were very sociable, sat in taverns, and listened to music. In the castle of the city, ancient Jewish tombstones from the years 1148 and 1217-31 survived. With the inclusion of the town in Nur al-Din’s (Noureddin) kingdom in 1146, security improved. *Benjamin of Tudela estimated in 1173 the number of Jews in Aleppo as 5,000 (according to the best-preserved manuscript versions, but according to another manuscript the number was only 1,500). Community leaders such as R. Moses Alcostan-dini, R. Israel, and R. Shet appear in the letters of the Gaon *Samuel ben Ali. After *Saladin’s death, Aleppo became the capital of an independent kingdom and until the middle of the 13th century the city enjoyed security and prosperity which the Jews shared. In 1217, Judah *Al-Harizi visited Aleppo and reported that there were several Jewish scholars, physicians, and government officials active there at the time. He noted the names of R. Samuel, who was a scribe in the court, and the physician Eleazar. Among other persons cited by him were R. Azaryahu, a descendant of the exilarch; R Samuel b. Nissim (hakham Nasnot), who was the head of the local academy; R. Yeshuah; R. Yachun; Shemarya and his sons Muvkhar and Obadiah; R. Joseph, the son of Hisdai; R. Samuel, who was the king’s scribe; and the physician Hananiah b. Bezalel. Al-H arizi died in Aleppo in December 1225. A famous scholar who lived in Aleppo during the 13th or 14th century was R. Judah *Al-Madari, who wrote commentaries on the Gemara. In 1014 Muslims plundered and destroyed Jewish and Christian houses. The great synagogue was under the authority of the Erez Israel gaon, and the small synagogue was under the authority of Babylonian geonim. In the *Seljuk period only two synagogues survived in the city. In the *Ayyubid period the Muslim authorities converted synagogues into mosques. In the days of al-Malik al-Tahir the Jewish cemetery and the Jewish gate were destroyed. Muslims used Jewish tombstones to reconstruct the castle. Throughout the Muslim period the Jewish community in Aleppo had considerable autonomy and organized institutions.

The Mongol conquest (1260) led to the slaughter of Jews, but the central synagogue, untouched by the invaders, offered asylum to many. The same year, the Mamluks defeated the Mongols and ruled over Syria until the beginning of the 16th century. Aleppo, their stronghold in northern Syria, contained a large garrison which brought further prosperity to the community. There were several wealthy merchants, officials, craftsmen, and outstanding scholars among the Aleppo Jews. The rich community maintained educational institutions and scholars. The growth of Muslim intolerance under rulers from Cairo and Damascus and the periodical publication of discriminatory laws against non-Muslims had their effect on the life of the community. In 1327, the synagogue was turned into a mosque with the approval of the sultan of Cairo and its name became the Al-Hayyat ("Snake") mosque. In the 13th century a group of ^Karaites lived in Aleppo, but they disappeared in the following centuries. The end of the 14th century saw a power struggle between opposing factions of the leaders of the Mamluks and heavy taxes were imposed on the civilian population. In 1400, Tamerlane captured Aleppo with much bloodshed and destruction. Many Jews were killed and enslaved. The community gradually overcame this disaster and in the second half of the 15th century Aleppo Jews again traded with India and scholars resumed their learned activities. In the Mamluk period (1260-1517) the Jews lived in the old quarter and were active as merchants. Between 1375 and 1399 R. David, the son of Joshua, the nagid of Egypt, settled in Aleppo. The nasi of the community c. 1471 was Joseph b. Zadka b. Yishai b. Yoshiyahu. R. Obadiah of *Bertinoro pointed out in 1488 that the Jews of Aleppo had a good income. According to a census, 233 Jewish families lived there during 1570-90, but the real number was probably higher.

At the beginning of the 16th century exiles from Spain started to arrive in Aleppo, among them outstanding rabbis. They established a separate community although sharing the general institutions with the mustaarbim (Orientals). The Jewish population increased markedly; the great synagogue (called, "the Yellow") could no longer accommodate all the congregation and in the second half of the 15th century an additional (eastern) wing was added where the Sephardim prayed. The leaders of the Musta’arab congregation were members of the Dayyan family until the 19th century – in the 16th century: Moses and Saadiah Dayyan; in the 17th: Morde-cai, Nathan, and Joseph Dayyan; in the 18th: Nathan, Morde-cai (d. 1733), Samuel (d. 1722), Joseph, and Mordecai (d. 1774) Dayyan. The communal leader of the Musta’arab congregation during the 16th century was the sheikh al-yahud. The spiritual and intellectual leadership of the community gradually passed to the Sephardim, and important rabbis include R. Solomon Atartoros in the middle of the 16th century and after him R. Abraham b. Asher of Safed, R. Moses Chalaz, R. Eliezer b. Yoh ai, and R. Moses Halevi Ibn Alkabaz, R. Samuel b. Abraham *Laniado, his son, R. Abraham (who officiated until 1623), and his grandson, R. Solomon. In the 16th century disputes broke out between the Musta’arab and the Sephardi congregations, but later the relations between them improved and they lived peacefully. The leader of the community in the beginning of the 18th century was Samuel Rigwan. Other famous rabbis in the 18th century were Joseph Abadi, Samuel Deweik Haco-hen (d. 1732), Samuel Pinto (d. 1714), Mordecai Asban, Judah Kazin, Zadka Hutzin, Gabriel Hacohen, Yeshayah Dabah, Michael Harari, David Laniado, H ayyim Ataya, Elijah Laniado, Isaac Antibi, Yeshayah Ataya, Ezrz Zaig, and Isaac Beracha. Famous scholars in the city in the same time period were the brothers Joseph (d. 1736) and Yom Tov Safsaya. From the end of the 17th century an academy (yeshivah) operated in Aleppo. In 1730 R. Eliya Silvera founded a Midrash Silvera and the first head of this institution was R. Yeshayah Dabah (d. 1772). R. Samuel Pinto was head of a bet midrash in the first half of the 18th century. Many of the above scholars wrote books on rabbinic subjects, most of them printed in Italy. In the 17th century significant Jewish manuscripts from Aleppo were bought in France and Britain. After the Ottoman conquest in 1517, constant contacts were established with the great communities in Constantinople and the other towns in Turkey, as were trade links with them and with Persia and India. Contacts with the Jews of Palestine were also close, and the influence of the Safed kabbalists was marked. Shabbateanism found many adherents in Aleppo, especially R. Solomon Laniado and R. Nathan Dayyan, R. Moses Galante and Daniel Pinto, and after *Shab-betai’s apostasy, *Nathan of Gaza went to Aleppo and continued his activities there. In 1684 R. Solomon Laniado wrote a letter as the rabbi of the two congregations.

The traveler Texieira estimated c. 1600 the Jewish population of the city at about 1,000 families, many of them wealthy. According to the census of 1672 there lived in the city 380 Jews who paid the jizya, most of them mustaarabs and 73 of Spanish origin. In 1695 there were 875 Jewish families. The Jews numbered about 5% of the city’s population in the Ottoman period. In 1803 the traveler Taylor estimated that there were only 3,000 Jews in the city.

In 1700, R. Moses b. Raphael Harari of Salonika was rabbi of Aleppo. He died in 1729. At that time, European Jews from France and Italy also settled in Aleppo; they participated in the extensive trade between Persia and southern Europe in which Aleppo served as an important station. These merchants, called ^Francos, enjoyed the protection of the consuls of the European powers and this created antagonism in the community. The Francos liberally supported communal institutions, but refused to pay the regular taxes and did not recognize the authority of the community. R. Samuel Laniado 11, rabbi of Aleppo in the first half of the 18th century, strongly demanded that the Francos have the same obligations as all other Jews in Aleppo and that all the rules should bind them. In the second half of the 18th century the dispute flared up again when the chief rabbi, Raphael Solomon (b. Samuel) Laniado, tried to compel the Francos to accept the rules of the community and was opposed by R. Judah Kazin, who defended the Francos; the latter, in protest, ceased to take part in public prayers. The dispute had a social background, since the Francos were wealthy and learned and were attached to the ideas and customs they brought from Europe. At the end of the 18th century, with the decline of trade between Aleppo and Persia, the number of Francos dwindled. The prominent families among the Francos included Ergas, Altaretz, Almida, Ancona, Belilius, Lubergon, Lopez, Lucena, Marini, Sithon, Selviera, Sinioro, Faro, Piccotto, Caravaglli, Rodrigez, and Rivero. There were also Jewish translators employed by the European consuls. The Ottoman authorities attempted to extort money from the Jewish translators by putting pressure on the Jewish community. The Jewish community, however, refused to release these translators from paying their share of the communal taxes.

From the 1520s until the mid-17a century, Jews as well as Christians filled the post of emini gumruk, that is, the chief officer of the local customs house charged with the collection of receipts. Many Jews died in the plagues which occurred during the Ottoman period. Many scholars in the community created halakhic literature, especially responsa, codes, homi-letics, exegesis of the Bible, and liturgy. There were also rabbis who created kabbalistic literature. Many of these scholars settled in Erez Israel.

Between 1841 and 1860 three *blood libels occurred in Aleppo. In June 1853 the Greek-Catholic patriarch accused the Jews of Aleppo of kidnapping a Christian boy for ritual purposes. Despite the tension between Jews and Christians in the city, the Picciotto family helped the latter. Only a few Jewish students studied in the Christian schools. In 1854 the rabbis of Aleppo declared a herem (boycott) on any relations with the Protestant missionaries who tried to proselytize Jews. From 1798 until the end of the 19th century several European states appointed European Jews who had settled in Aleppo as their consular representatives. The first was Raphael Picciotto, who was appointed in 1798 consul of Austria and Toscana, and other members of his family were later appointed consuls of other states. Another Raphael Picciotto was consul of Russia and Prussia between 1840 and 1880; the consul of Austria-Toscana was Elijah Picciotto and after his death in 1848 his son Moses inherited this office. The consul of Holland was Daniel Picciotto and of Belgium Hillel Picciotto. The consul of Persia was Joseph Picciotto and of Denmark Moses Picciotto, of Sweden and Norway Joseph Picciotto, and of the U.S. Hillel Picciotto. In the 18th century many local Jews acquired French or British citizenship. Until 1878 the French consul’s attitude to Jews was negative, following the policy set by the consul Bertrand during his years in Aleppo (1862-78), but from 1878 the policy was changed by the consul Destree. British consuls protected the Jews of Aleppo throughout the century.

The hakham bashi in Aleppo was the supreme spiritual authority and from the 1870s there were two chief rabbis. The chief rabbi in 1858-69 was Hayyim Lebton, and after his death Saul Duwek (d. 1874), Mennaseh Sithon (1874-76), and Aaron Sheweika in the year 1880. The later rabbis were Moses Hacohen and Moses Sewid. The Francos established in the 18th century two schools for orphans and poor children. A great yeshivah was active. In 1862 the vali imprisoned R. Raphael Kazin, and freed him only under the order not to establish a Reform community in Aleppo. In 1865 a book by R. Elijah b. Amozeg of Leghorn, Am le-Mikra, was burned in Aleppo. In 1868 the first Jew was appointed to the meclis (city council) of Aleppo. From 1858 on Jews officiated in the mercantile court of law in Aleppo. In 1847, 3,500 Jews lived in the city, and in 1881, 10,200. During most of the Ottoman period Aleppo had the largest Jewish community in Syria. The majority of its Jews belonged to the middle class and were known as diligent merchants and agents. The local government, the European consuls who lived in the city, and the European agents of the trading companies recognized the economic power of Aleppo’s Jews. A few Jews also had roles in the administration of the Vilayet of Aleppo, for the most part as tax collectors, custom officers, and *sarrafs, some earning vast amounts from these positions in addition to their own businesses.

In the first half of the 19th century, the status of the community declined both economically and culturally. At the same time hostilities erupted between the various religious communities in Syria. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 greatly affected the international trade of the Jewish merchants of Aleppo. In 1875, a blood libel was spread about the Jews of Aleppo; however, the missing Armenian boy, whose absence had provided the charge, was found in a nearby village. In1869 the *Alliance Israelite Universelle established a school for boys with 68 students from the wealthy families and 15 children from needy families, but most of the latter left the school. In 1873 the school was closed and in 1874 it was reopened. In 1872 the Alliance established a school for girls, with 20-30 students, utilizing European teaching methods. It was closed and reopened a few times and only in the 1890s did it operate at full capacity. In 1865 Abraham Sasson and his sons set up a printing house in Aleppo, one of the sons having learned the craft in Leghorn. In 1887 Isaiah Dayyan established another printing press with the help of H.P. Kohen from Jerusalem. Two years later they had to cease operation, not being able to obtain a government license. The license was obtained in 1896 and printing resumed and continued until World War 1. Having learned the craft with Eliezer *Ben-Yehuda in Jerusalem,Ezra H ayyim Jouegati of Damascus set up and operated a press from 1910 to 1933. Another printing press was founded by Ezra Bijo in 1924 and continued until 1925. Altogether, approximately 70 books were printed in Aleppo, mostly works by local scholars, ancient manuscripts found locally, and prayer books of the local rite. From the 1850s immigrants from Aleppo settled in Western cities like Manchester and opened firms there. The immigration of Jews from Aleppo to other countries and to Erez Israel was limited until the 1870s and the majority of the immigrants settled in Egypt, but in the 1880s and 1890s it grew and became a flood as thousands traveled to North and South America. The immigrants wished to improve their socio-economic circumstances. Many Jews from Aleppo emigrated to Beirut as well from the middle of the 19th century until the 1940s. After World War 1 there were over 6,000 Jews in Aleppo. The wealthy moved from the Jewish quarter, which was surrounded by a wall, to new quarters. However, the link with Jewish culture was not severed; traditional learning was not neglected and a few hundred immigrated to Palestine. In 1931 there were 7,500 Jews in Aleppo, of whom 3,000-3,500 were poor laborers. In particular among the others were merchants and brokers, and some 20 Jews were wealthy and had big firms while five or six were bankers.

There are descriptions from the years 1931 and 1934 of the impoverishment of Aleppo Jewry. Most of the immigrants to Erez Israel were needy. In the 1940s many Jews immigrated through *"illegal" immigration (Aliyah Bet). In the year 1944, in the wake of the deteriorating political and economic situation of the community, 510 emigrated from Aleppo to Erez Israel. In 1945 many children and young men immigrated to Erez Israel. The police accused the leader of the community of Aleppo, Rachmo Nechmad, of aiding the secret immigration to Erez Israel. Among the scholars of the first half of the 20th century were R. Ezra Abadi, R. Abraham Salem, R. David Moses Sithon, R. Elijah Lopez, R. Judah Ataya, R. Abraham Isaac Dewik, and R. Isaac Shehibar.

In 1947, Aleppo had a Jewish community of about 10,000. In an outbreak of violence against the Jews in December 1947, all the synagogues were destroyed and about 6,000 Jews fled the city. Many of them secretly crossed the frontier into Turkey or Lebanon, where they settled, or continued to Israel, Europe, or America. On December 1, 1947, anti-Jewish riots broke out in the Jewish quarter of Aleppo. About 150 buildings, 50 shops and offices, ten synagogues and five schools were damaged; 160 old Torah scrolls from the Bahsita synagogue were burned. The leaders of the community preserved the famous Keter Aram Zova. Thanks to their efforts most of the scroll arrived in Israel. In November 1947 the Jewish Telegraph Agency reported that 22 Jews from Aleppo had been arrested when they tried to pass the frontier between Lebanon and Israel. There are other reports about many Jews from Aleppo who tried to escape to Israel. The Jews also suffered under the reign of Colonel Adib Shishakli (1949-54). The principal leaders of the community in 1953/1954 were Chief Rabbi Moses Mizrachi, who was 90 years old, R. Za’afrani, and Selim Duek. The latter was a wealthy merchant who had relations with the local authorities. According to a report by the president of the Beirut community in 1959, around 2,000 Jews lived in Aleppo then. The 1,000 Jews living in Aleppo in 1968 resided in two quarters: Bahslta, the old quarter; and Jamiliyya, founded after World War 1. Muslims, who had moved into these quarters after the departure of the Jewish residents, occasionally assaulted their Jewish neighbors and several cases of murder were recorded. The four schools of the Alliance Israelite Universelle were closed by the government in 1950, and thereafter most of the children studied at a religious elementary school (talmud torah). As the community dwindled, this school was also closed, and some Jewish children studied at Christian schools. A special prayer-custom, the Aram-Z obah rite, existed in Aleppo (its prayer book was printed in Venice, 1523-27). In July 1967 Jewish teachers were dismissed and degrading regulations against the Jews were issued by the government. In that year only 1,500 Jews were living in Aleppo. The Jews of Aleppo in the last generation tried to maintain their Jewish identity. They published lectures by Edmond M. Cohen, which were distributed at great risk in the 1970s and 1980s. This was the last book produced by the remnants of the community.

Aleppo immigrants in Buenos Aires in the 1920s, under the leadership of R. Saul Sithon Dabbah, lived traditionally, as in Aleppo. During the 1930s, integration into the life of Argentina increased and with it came a decline in religious and ethnic identity. This trend reversed itself after one more generation, under the guidance of R. Isaac Shehebar.

Musical Tradition

Syrian Jewry and, particularly, the community of Aleppo long enjoyed a reputation as lovers of music and singing. In the course of eight centuries, they developed a characteristic style in their liturgical and related activities. As early as the 13th century, the Spanish Hebrew poet Judah *Al-H arizi, referring to Syrian personalities, mentioned the cantor R. Daniel and said his performance conquered "the hearts of the holy people by his delightful song" (Tahkemoni, 46). From about the same time we have evidence concerning the adoption and singing in Aleppo of the Arabic poetical strophic genre called muwashshah (Hebrew shir ezor) invented in Andalusia by the beginning of the 10th century. This new genre, soon after its creation, gained great favor and knew wide circulation. One can infer from the question concerning its singing addressed by the Jews of Aleppo to Maimonides that it was already then popular among them and that it probably provoked the dissatisfaction of the rabbinical authorities. Their question was whether the singing of Arabic muwashshah at (plur. of muwashshah.) with instrumental accompaniment was permitted. The question probably implied secular and/or paraliturgical singing.

Almost all the chants and hymns sung outside the formal religious service were the work of distinguished Aleppo rabbis such as Moses Laniado, Raphael Antebi, Jacob and Morde-cai Abbadi, and Mordecai Levaton, who were poets as well as composers. Some of them may have modeled themselves on the poet Israel *Najara of Damascus who was highly esteemed by composers of the period. This encouragement of the art of singing by the rabbis found strong support in R. Mordecai Ab-badi’s introduction to a book of bakkashot (Sephardi hymns), Mikra Kodesh, published in 1873. The melodic style of Aleppo belongs to the Arabian-Turco-Persian musical family, but also shows other influences, mainly those of Sephardi Jews. Both in prayers and other songs, the *maqam style (melodic pattern) and elaboration prevail. For each Sabbath or festival prayer there is an appropriate maqam, and the various zemirot (hymns) also conform to the maqam pattern.

The Aleppan musical tradition was instrumental in the evolution of the Sephardi-Jerusalemite style, which currently dominates the entire realm of the liturgical and paraliturgical in many Oriental communities in Israel. It probably started with the singing of bakkashot and its fascinating dissemination and wide adoption by many immigrant groups. The establishment of formal cantorial training seminaries in the last decades certainly was determinant in consolidating the style toward which most of the generation of the Israeli-born Oriental cantors inclined.