The invention: A scale for measuring the strength of earthquakes based on their seismograph recordings.

The people behind the invention:

Charles F. Richter (1900-1985), an American seismologist Beno Gutenberg (1889-1960), a German American seismologist Kiyoo Wadati (1902- ), a pioneering Japanese seismologist Giuseppe Mercalli (1850-1914), an Italian physicist, volcanologist, and meteorologist

Earthquake Study by Eyewitness Report

Earthquakes range in strength from barely detectable tremors to catastrophes that devastate large regions and take hundreds of thousands of lives. Yet the human impact of earthquakes is not an accurate measure of their power; minor earthquakes in heavily populated regions may cause great destruction, whereas powerful earthquakes in remote areas may go unnoticed. To study earthquakes, it is essential to have an accurate means of measuring their power.

The first attempt to measure the power of earthquakes was the development of intensity scales, which relied on damage effects and reports by witnesses to measure the force of vibration. The first such scale was devised by geologists Michele Stefano de Rossi and Franjois-Alphonse Forel in 1883. It ranked earthquakes on a scale of 1 to 10. The de Rossi-Forel scale proved to have two serious limitations: Its level 10 encompassed a great range of effects, and its description of effects on human-made and natural objects was so specifically European that it was difficult to apply the scale elsewhere.

To remedy these problems, Giuseppe Mercalli published a revised intensity scale in 1902. The Mercalli scale, as it came to be called, added two levels to the high end of the de Rossi-Forel scale, making its highest level 12. It also was rewritten to make it more globally applicable. With later modifications by Charles F. Richter, the Mercalli scale is still in use.

Intensity measurements, even though they are somewhat subjective, are very useful in mapping the extent of earthquake effects. Nevertheless, intensity measurements are still not ideal measuring techniques. Intensity varies from place to place and is strongly influenced by geologic features, and different observers frequently report different intensities. There is a need for an objective method of describing the strength of earthquakes with a single measurement.

Charles F. Richter

Charles Francis Richter was born in Ohio in 1900. After his mother divorced his father, she moved the family to Los Angles in 1909. A precocious student, Richter entered the University of Southern California at sixteen and transferred to Stanford University a year later, majoring in physics. He graduated in 1920 and finished a doctorate in theoretical physics at the California Institute of Technology in 1928.

While Richter was a graduate student at Caltech, Noble laureate Robert A. Millikan lured him away from his original interest, astronomy, to become an assistant at the seismology laboratory. Richter realized that seismology was then a relatively new discipline and that he could help it mature. He stayed with it— and Caltech—for the rest of his university career, retiring as professor emeritus in 1970. In 1971 he opened a consulting firm—Lindvall, Richter and Associates—to assess the earthquake readiness of structures.

Richter published more than two hundred articles about earthquakes and earthquake engineering and two influential topics, Elementary Seismology and Seismicity of the Earth (with Beno Gutenberg). These works, together with his teaching, trained a generation of earthquake researchers and gave them a basic tool, the Richter scale, to work with. He died in California in 1985.

Measuring Earthquakes One Hundred Kilometers Away

An objective technique for determining the power of earthquakes was devised in the early 1930′s by Richter at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. The eventual usefulness of the scale that came to be called the “Richter scale” was completely unforeseen at first.

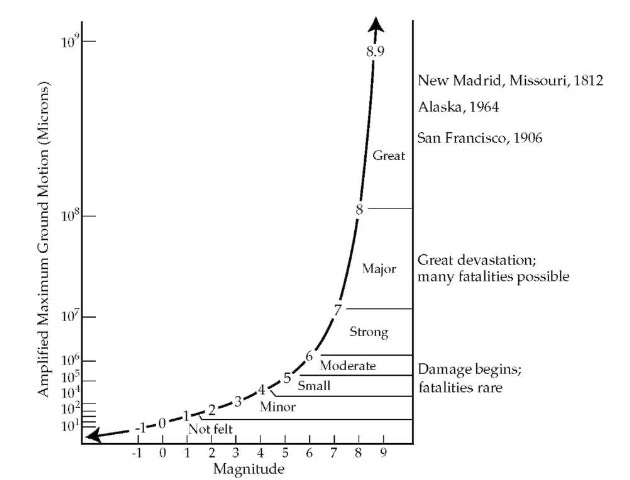

Graphic representation of the Richter scale showing examples of historically important earthquakes.

In 1931, the California Institute of Technology was preparing to issue a catalog of all earthquakes detected by its seismographs in the preceding three years. Several hundred earthquakes were listed, most of which had not been felt by humans, but detected only by instruments. Richter was concerned about the possible misinterpretations of the listing. With no indication of the strength of the earthquakes, the public might overestimate the risk of earthquakes in areas where seismographs were numerous and underestimate the risk in areas where seismographs were few.

To remedy the lack of a measuring method, Richter devised the scale that now bears his name. On this scale, earthquake force is expressed in magnitudes, which in turn are expressed in whole numbers and decimals. Each increase of one magnitude indicates a tenfold jump in the earthquake’s force. These measurements were defined for a standard seismograph located one hundred kilometers from the earthquake. By comparing records for earthquakes recorded on different devices at different distances, Richter was able to create conversion tables for measuring magnitudes for any instrument at any distance.

Impact

Richter had hoped to create a rough means of separating small, medium, and large earthquakes, but he found that the scale was capable of making much finer distinctions. Most magnitude estimates made with a variety of instruments at various distances from earthquakes agreed to within a few tenths of a magnitude. Richter formally published a description of his scale in January, 1935, in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. Other systems of estimating magnitude had been attempted, notably that of Kiyoo Wadati, published in 1931, but Richter’s system proved to be the most workable scale yet devised and rapidly became the standard.

Over the next few years, the scale was refined. One critical refinement was in the way seismic recordings were converted into magnitude. Earthquakes produce many types of waves, but it was not known which type should be the standard for magnitude. So-called surface waves travel along the surface of the earth. It is these waves that produce most of the damage in large earthquakes; therefore, it seemed logical to let these waves be the standard. Earthquakes deep within the earth, however, produce few surface waves. Magnitudes based on surface waves would therefore be too small for these earthquakes. Deep earthquakes produce mostly waves that travel through the solid body of the earth; these are the so-called body waves.

It became apparent that two scales were needed: one based on surface waves and one on body waves. Richter and his colleague Beno Gutenberg developed scales for the two different types of waves, which are still in use. Magnitudes estimated from surface waves are symbolized by a capital M, and those based on body waves are denoted by a lowercase m.

From a knowledge of Earth movements associated with seismic waves, Richter and Gutenberg succeeded in defining the energy output of an earthquake in measurements of magnitude. A magnitude 6 earthquake releases about as much energy as a one-megaton nuclear explosion; a magnitude 0 earthquake releases about as much energy as a small car dropped off a two-story building.

See also Carbon dating; Geiger counter; Gyrocompass; Sonar; Scanning tunneling microscope.