SHIGETO TSUKIE FIRST TOOK MELINDA and me to Miyama-cho in 2001, and we returned two years later in better weather to catch the early winter light. I’d been curious to know what had become of this remote area in the mountains north of Kyoto since seeing Norman Carver’s black-and-white photographs from the 1950s. Taken when Carver was a Ful-bright scholar studying form and space in traditional Japanese architecture, his images of Kitamura (Kita village) record thatch-roofed houses and farm buildings clustered against the mountainside in a scene little changed over centuries. On previous trips to Japan I’d become familiar with miscanthus thatching from shrines, temples, and museum preservations of traditional structures, but I hoped to learn more about how miscanthus, as a local material, fit into active community life.

The road to Kitamura is now well-paved; however, I was delighted to find much of the village and its remarkable structures intact. The Japanese government has recognized the site as a national treasure and offers assistance to villagers maintaining the thatching tradition. Preservation efforts extend far beyond the roofs: Kitamura is one of only six rural districts in Japan that officially recognize the entire landscape in the preservation area, including homes, household gardens, rice fields, Shinto shrines, and the surrounding Cryptome-ria-forested mountains.

We stayed in a thatch-roofed house during our second visit, and with Shige-to’s help I asked the owner if he knew who in the village might be knowledgeable about miscanthus. He provided introduction to his neighbor Hiroyuki Shindo, a renowned indigo dye artist and former Kyoto University professor who heads the village kaya (thatching) association. Shindo welcomed us to his house and garden, and explained that, although Miscanthus sinensis (su-suki) is typically used for village roofs, in the past M. tinctorius (kariyasu) had been valued for its great durability. Once fairly common in the local flora, this smaller species had become too scarce to provide adequate thatch. Shindo showed us plants in his garden grown from seed he’d collected from population on a local mountainside. The plants were shorter, strictly upright, and more refined than M. sinensis. Shindo’s interest in these plants was not for thatching, but for dye (the specific epithet tinctorius literally means of dyes), and he showed us some homespun material he’d dyed bright yellow using the miscanthus.

We walked Kitamura’s quiet streets and paths until dark, lingering among miscanthus recently harvested and neatly tied and stacked to dry. A few self-sown plants, uncut, stood casually in view of aging thatched roofs so green with moss that they were once again alive. By the time we departed, I’d developed a renewed appreciation for miscanthus.

The care and artistry evident here suggest a deep appreciation of the visual pleasure of a utilitarian process. As a species we’ve lived close to grasses longer than we’ve produced written histories, so in many ways it is surprising, particularly in Western cultures, that grasses have only recently found their place among the things we find both useful and beautiful.

Late afternoon light illuminates a self-sown miscanthus plant along a village path. The nearby roof, made of miscanthus thatch, supports a rich community of mosses. The distant mountains are clothed in Japanese cedar, Cryptomeria japonica.

Toward a Global Garden Ethic: Balancing Preservation and Sustainability

Preservation of local and regional landscapes, the relative merits of “native” vs. “exotic,” and true sustainability are intimately linked issues that must be reconciled in any thoughtful, ethical approach to grasses in the twenty-first century. Sounds complex, and it is, but we’re all engaged in this discussion every time we buy a plant, put spade to earth, or plan a garden. Because it is such an iconic “ornamental grass,” miscanthus provides a fine lens through which to view these issues.

Thinking back on my earliest gardening experiences, I recall that miscan-thus was the first grass I grew. I was living in northern Delaware, and mis-canthus thrived in the nearly impossible clay soil of my tiny urban garden. It was practical, undoubtedly beautiful, and seemed reasonably in sync with my local seasons. My garden’s ultimate mission was to reflect the plants, patterns, and processes that I knew and loved in surrounding woodlands and meadows, but I learned from experience that many local species that thrived in intact habitats quickly succumbed when subjected to my garden’s conditions, despite being watered and otherwise aided. Through observation, trial and error, I eventually developed a plant palette that served my purposes, but the miscanthus made a lasting impression for its ability to sustain itself without supplemental irrigation, pesticides, or fertilizer.

Resting on cedar shingles, a thatcher trims miscanthus stalks from a patch he’s making to one of Kitamura’s traditional roofs. The cedar shingles and miscanthus thatch are both local, renewable resources.

Dyed yellow from Miscanthus tinctorius, a bit of homespun material sits on a tatami mat (woven from native Juncus species) in Hiroyuki Shindo’s historic thatch-roofed house in Kitamura.

When I first traveled to Japan in the 1980s for Longwood Gardens, I was delighted by advertisements inside Tokyo train cars featuring the twin symbols of autumn: Japanese maple (momiji) leaves and miscanthus (susuki) flowers. I had only to look out the window to see the real thing adorning much of the trackside landscape. The mission of that first trip was to bring back cultivated selections of Japanese plants, and I learned a lot about Japan’s reverence for miscanthus from knowledgeable gardeners and nurserymen. The single discordant note came during a discussion with a young environmental biologist named Tanaka (whom I greatly admired) whose work was focused on subtropical Asia. He could understand his country’s traditional fondness for miscanthus but was surprised that we were importing it to North America, because from his perspective, it was “such a weed.” Tanaka wasn’t concerned with the nuisance of weeding out errant Miscanthus sinensis seedlings from a residential garden: he knew of the potential for this extraordinarily vital species to disrupt the frequently fragile balance of other ecosystems.

More than two decades have passed since I rode those Tokyo trains, and miscanthus has since attracted an impressive array of promoters and critics. It has been lauded as a beautiful plant possessing the necessary genetic diversity to enrich gardens or to provide a sustainable option for greening toxi-fied urban brownfields. It has been denigrated as an uncontrollable spoiler of native habitats and as an agent in the unfortunate homogenization of world landscapes. These conflicting viewpoints can be true or false: context is the ultimate arbiter. It’s up to each of us to adopt a set of rules—an ethic—that guides us in our professional work and our personal gardening. A garden ethic constantly evolving from local observation and continuously reviewed in regional and world context is most likely to result in preserving what we love and sustaining what we need in this global garden we all tend.

The Nature of Nature: The Nature of Grasses

Emerson’s wording is dated, but his message is modern. He’s suggesting humanity’s cultural landscapes are vital parts of one whole. Traditional ideas of nature are based upon a dichotomy: a “natural world” of untrammeled nature distinct from the “artificial world” of human invention. As appealing as the notion of an independently sublime, healing nature may be, the difficulty with the dichotomy is that it obscures the real role and responsibility of our species. Human influence is now so pervasive that it reaches virtually all parts of the globe. Recognizing this, the logical response is to take stock, identify goals, and behave like responsible managers.

I’ve been involved in more than one landscape project involving a degraded habitat during which someone has naively suggested that we simply “let nature take its course,” as if some benign independent force would make things right without our effort. The challenge is to identify an appropriate level of human influence versus human control. Twentieth-century landscape architects with a regional focus frequently viewed nature as the source or authority for their designs, establishing ethics and strategies based upon the messages they “read” in the landscape. For Frank Lloyd Wright, the purpose of design was to improve upon nature, and his designs were often strong writings on the landscape. Jens Jensen believed in a gentler hand, going so far as to suggest in Siftings (1939), “Nature talks more finely and deeply when left alone.” Jensen’s designs did, of course, intervene, and he was perhaps at his best when acting as an observant editor.

I subscribe to Raymond Williams’s (1980) definition of nature: “a singular name for the real multiplicity of things and living processes.” If we adopt this inclusive approach, valuing living process and welcoming the inevitable changes resulting from such dynamics, then the whole world again fits within a redefinition of the garden as “the theater that intrigues” (Stilgoe 1998). Interested in dynamics and intrigue? Look to the grasses.

Miscanthus sinensis brightens the trackside landscape in this photograph taken through the front window of a moving train heading toward Takayama in the Japanese Alps. This is a perfect example of a native plant as opportunist. The miscanthus is an integral part of the local ecology, commonly growing along the sunny banks ofthe nearby river. If we recognize the river margin as the natural habitat of this grass, then what do we say about the miscanthus on the right-of-way, which is clearly an artificial habitat (resulting from deliberate human activity) if one makes such distinctions? The miscanthus is simply an adaptable plant taking advantage of suitable growing conditions. Is it an exotic here? Is it a harmful invasive? It’s a weed from the perspective of railroad management. What would qualify as the native flora of a railroad right-of-way? Ifwe’re willing to update our definitions we can avoid such semantic entanglement and simply say that the miscanthus is a local plant growing in a local habitat. On this afternoon I was content to enjoy the whole scene as a continuous garden.

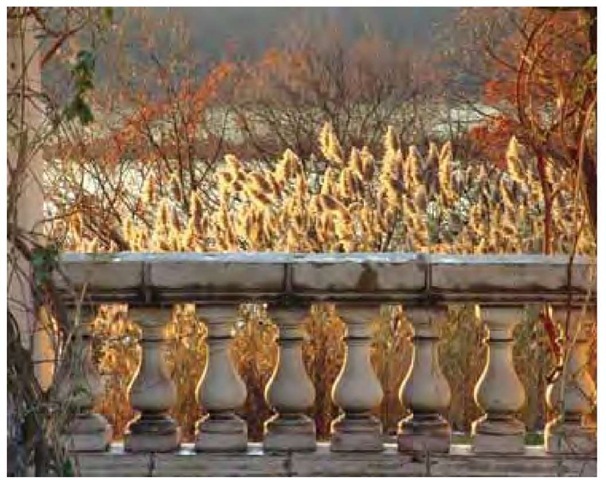

Beauty or the Beast? This view west across the Hudson River at sundown over the Rose Garden balustrade on the Bard College campus has much to say about the changing nature of grasses in our modern landscape. Hudson River School painter Frederic Edwin Church made his home, Olana (1870-1871), upriver from this point, taking advantage of views across the river to the Catskill Mountains. Phragmites is absent from Church’s period landscapes not because he painted at such grand scale, but because Phragmites in vast sweeps is a newcomer to the scene.

Unlike the Miscanthus sinensis moving about modern Japan, which is of Japanese origin, Phragmites australis in eastern North America is of mixed origin, including genotypes (genetically similar types) evolved in North America and other genotypes introduced inadvertently from exotic habitats. So variable in characteristics that it was once considered to represent two species (P. communis and P. australis), P. australis is a cosmopolitan grass occurring on every continent except Antarctica. Its presence in eastern North America is documented by herbarium records from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, qualifying it as “native” by common measure. The explosive growth of this species in the late twentieth century has been scientifically attributed (in particular by Bernd Blossey and Cornell University researchers) almost exclusively to introduced genotypes. In short, this single grass species may be “native” or “exotic” depending upon its genetic origin.

Controlling the exotic Phragmites is highly problematic. In small-scale and localized landscapes, mechanical and/or chemical methods can be effective, with lasting results. In larger, dynamic landscapes, such as regional river systems, mechanical methods are impractical and chemical methods ultimately prove futile, unless the regular application of toxic herbicides to regional waters is judged desirable. Until better management techniques are developed, the healthiest, most realistic approach is to accept scenes like this as genuine elements of the Hudson River Valley’s twenty-first century landscape.

At first glance I imagined I was looking at the planet, with continents spread across light blue oceans. In truth it is more like looking at the world dehydrated. The view is of the bottom of a derelict, empty steel swimming pool in what once was a very elegant private garden. Common cattail, Typha latifolia, which typically grows in deep soils in standing water, is clearly capable of surviving in a couple inches of leaf litter accumulating on an occasionally rainsoaked painted-metal surface. Such resilience and adaptability are the makings of the perfect weed in the wrong situation; however, those same traits may be the very answer for vegetating increasingly arid habitats and cultural landscapes.

Hand-hewn granite retaining walls, built over a century ago by the Pennsylvania Railroad, still support elevated tracks along the Northeast Corridor, the busiest stretch of rail in the United States. The artwork is unsanctioned, and the entire ensemble, complete with an orderly fringe of switchgrass, Panicum virgatum, has for years been a highlight of my landscape experience on the way to the Philadelphia airport. No person planted the switchgrass. Panicum populations along the adjacent Delaware River provided the seed source, and this sturdy local plant found a niche between the ballast and the sheer edge. I’m fond of the way the tawny winter color of the grass picks up the black and ruddy browns in the stone and rails. I’m amused by the strict verticality of the switch-grass playing off the granite courses, and by the visual order of the grasses stepping down in unison with the stone. No mulch, no hose. A sustainably fine design.

Iconic Grasslands: Prairie to City

Gardens celebrating dominion over nature certainly had their day, and many of the results are enduringly dramatic, if admittedly high maintenance. Gardens celebrating regional ecologies, or increasingly, evoking lost landscapes, are more the current model. Grasses as a group are in no danger of extinction; however, few grasslands have survived intact past the twentieth century. The North American tallgrass prairie is perhaps the most iconic of great grasslands that have been reduced to remnants. Less than four percent of the original 400,000 square miles (1,035,995 square kilometers) has been left unplowed or undeveloped. Once a familiar home to North American Indian tribes, then a forbidding and often lethal realm for pioneers venturing west, the vast sea of grasses punctuated by perennial flowers has survived mostly as an emblem of sunlit wilderness. Some wonderful patches of prairie have been preserved, including Bluestem Prairie Preserve in Minnesota, Prairie State Park in Missouri, and Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas, and others have been rebuilt or restored; however, the newest iterations of the prairie are sprouting internationally in suburban and urban spaces.

Many grasslands that we take for granted as native are not. California still has a rich and diverse grass flora; however, the golden glow of the state’s signature coastal landscapes is now primarily due to exotic grasses introduced for a multitude of human purposes. Native or not, it is difficult to deny the appeal of this mix of grasses and California oaks in Santa Barbara County in mid August.

The prairie, tallgrass and shortgrass, translates with relative ease to the city, not as a literal re-creation but as an abstraction. As with the original prairie, the urban prairie is built on a foundation of sturdy perennial grasses. This durable, drought-tolerant matrix is adaptable to a wide range of urban and suburban conditions and can cover large areas at relatively low cost, with florifer-ous perennial herbs contributing periodic interest throughout the seasons. In the process of abstraction, the prairie has become the “praerie/’ This is more than a variation in national spellings (North America versus northern Europe). The “praerie” retains the grass/forb mix but employs species from globally diverse sunny habitats. Visually rich but lacking many of the ecological dynamics of authentic prairie systems, the “praerie” is a new type of garden, in sync with human habitat.

Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in the Flint Hills of Kansas stretches over 10,000 acres (ca. 4000 ha) in the historic heart of the prairie. In this late-February view a path curving through big bluestem, Andro-pogon gerardii, and other tallgrass species directs the eye to a bur oak, Quercus mac-rocarpa, in a draw and to a distant school-house built of local limestone in the 1880s.

This isn’t Kansas, and it isn’t the tallgrass prairie, though it provides an approximation of what the prairie would have looked like ablaze. More than 30 feet (9 m) tall, flames are racing uncontrolled across Phragmites australis in the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum one mile (1.6 km) from the Philadelphia airport. I took this photograph more than 100 yards (91 m) away from the fire, yet the heat was almost scorching.

Induced by lighting and by North American Indian peoples, fire was an integral part of prairie ecology, and without it the prairie as we know it would never have existed. Unless a powerful limiting factor is present, such as fire or deep water, grasslands in areas of moderate rainfall usually revert to forest.

This stretch of State Route 91 in Dodge County, Nebraska, is classic Americana and appears entirely uncontrived.

Intermingling with nearby grasses, Salvia azurea, known as pitcher sage or blue sage, mirrors the color of the prairie sky.

The vernacular form of the grain storage facility in the distance combines with Indian grass, Sorghastrum nutans, and Maximilian sunflower, Helianthus maximilia-nii (in the foreground), to tell a story of the contemporary Nebraska landscape. In fact, the prairie grasses and wildflowers owe their existence in part to the deliberate stewardship of Nebraska’s Department of Roads.

Piet Oudolf’s design for urban Chicago’s Millennium Park is deeply textural, like its prairie progenitor. Frank Gehry’s architecture fills in nicely in the absence of a grain silo. The composition of the plantings is unmistakably evocative of the prairie even though the actual species employed are a mix of North American and Eurasian origin.

A continuous sweep of switchgrass, Panicum virgatum ‘Heavy Metal’, in the redeveloping waterfront of Wilmington, Delaware, can be read as the prairie or, more locally, as a nod to similar scenes occurring in habitats along the state’s coastal waters.

Hans Simon’s grassy planting on top of Herrenhausen’s Rain Forest House in Hanover, Germany, is a visionary, ecologically inspired response to the challenge of greening the elevated urban habitat. His design is especially fitting for this building, which stands in place of the Great Palm House destroyed in the Second World War. The roof garden demonstrates strategies for dealing with one of the world’s driest environments: the urban roof. Looking to European flora for models and materials, Simon’s design introduces tough grasses and sedges, including Sesleria rigida (center) and Carex humilis (right foreground).

Julie Messervy’s design for Toronto’s Music Garden reclaims and enlivens another urban waterfront that had once succumbed to industrial neglect. It includes both generous sweeps and intimate spaces, employing grasses and real stone to bring a bold dynamic within reach of new urban residential development. Here feather-reedgrass, Cala-magrostis xacutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’ (foreground), and switchgrass, Panicum virgatum (background), create a gentle enclosure.

Christchurch has long been celebrated as a Garden City and as the most English of New Zealand’s cities. Evolving sensibilities are bringing more of the South Island’s ecological legacy into Christchurch’s urban landscape, while holding on to history. Cutting diagonally across the city’s downtown grid, the Avon River’s once-eroded banks are now stable and lushly vegetated with New Zealand tussock sedge, Carexsecta. Sponsored by Christchurch City Council programs for restoring waterways and national character, this design draws directly from the sedge’s typical habitat while simultaneously enhancing the formal character of the Gloucester Street Bridge and other classic architecture.

Grasses in Context: Style Fit to Place

More than two centuries ago, the French writer Chateaubriand suggested: “Ideas can be, and are, cosmopolitan, but not style, which has a soil, a sky, and a sun all its own.” I’ve always found these words illuminating when applied to garden style. It seems so sensible that of all art forms gardens should recognize local context and conditions, both environmental and cultural. As the garden palette of grasses continues to expand and develop, it is ever easier to employ grasses for this purpose.

Landscape architect Karl Wienke’s design for his own water garden in Suhl, Germany, combines formal architectural elements with highly naturalistic planting arrangements. A diversity of moisture-loving sedges including Carexsiderosticha, C. musk-ingumensis, Schoenoplectus tabernaemon-tani, Cyperus longus, and Carexpendula are positioned in appropriate moisture zones around the pond margin. The elegant result of this highly structured design could almost be mistaken for a naturally occurring aquatic habitat.

It would be easy to believe this exquisite textural composition is possible only by gathering plants from a multitude of faraway places, but in fact it draws only from the practicality, beauty, and diversity of the New Zealand flora. Carex flagellifera spills gracefully over the walls of this demonstration garden at the Taupo Native Plant Nursery on the North Island.

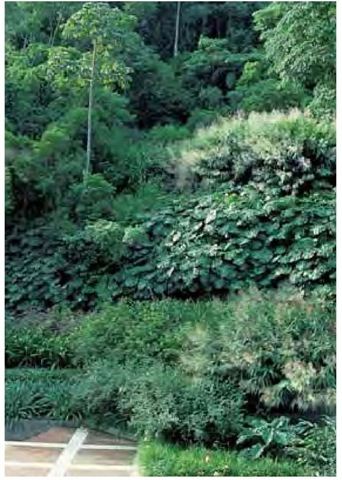

Juxtaposition of tiger grass, Thysano-laena latifolia, and Philodendron selloum in the Martins Garden near Petropolis, Brazil, boldly expresses the textural drama of the tropics. The late designer, artist, and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx combined his extensive knowledge of tropical flora with his painter’s eye to develop a style that became synonymous with his native Brazil.

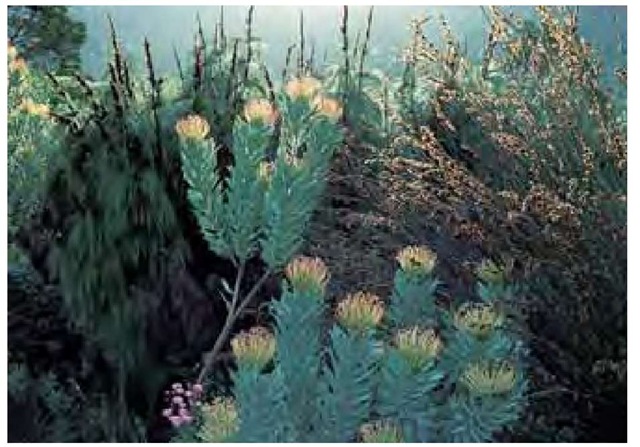

Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden in Cape Town, South Africa, is dedicated exclusively to the study and display of indigenous flora, which includes hundreds of species of restios—close relatives of grasses, sedges, and rushes. This focused environmental mission manages to create a myriad of compositions and associations that also qualify as stylishly fine design. In this view, restios Elegia capensis and Tham-nochortus insignis mingle with the rare protea Leucospermumformosanum in the late-afternoon light.

Southern California has often been mistaken for a tropical paradise, but in fact it is a desert. Quail Botanical Gardens in Encinitas demonstrates a waterwise garden style that is eminently sensible for public and private landscapes. Moving to early July breezes, Peruvian feather grass, Jarava ichu, plays against the sculptural form of Shaw’s agave, Agave shawii, and other southwestern North American desert species.

Beth Chatto’s gravel garden in Colchester, England, has not been artificially watered since its creation during the winter of 1991-92. Drought-tolerant grasses, including Mexican feathergrass, Nassella tenuissima, and Mauritania vine reed, Am-pelodesmos mauritanicus, evident in this view, contribute year-round interest. The water-conserving ethic is the basis for this garden’s style, which makes use of an eclectic mix of plants from diverse but dry global habitats.

This winter morning view of the gravel garden at Knoll Gardens in Dorset demonstrates the drama possible in an unir-rigated landscape even during England’s dimmest season. The eclectic but regionally adapted mix of grasses includes Pennisetum macrourum (foreground) from South Africa, Muhlenbergia rigens (rear center) from California, and Miscanthus nepalensis (rear right) from Asia.

Expanding the Palette

Although the garden palette of grasses, sedges, rushes, restios, and cattails is hugely expanded from even a few decades ago, it still represents a fraction of the potential. How do we recognize the garden grasses of the future, and how do we gather the material and information necessary for them to thrive in tomorrow’s landscapes? There is no better place to begin than by closely observing the places in which we live.

Lecture travels in New Zealand in September (early spring) 2005 afforded the opportunity to visit again with Gordon Collier and his wife, Annette, two gardeners who know their country and its flora. We spent a day exploring Tongariro National Park in the North Island’s volcanic central region and came upon scene after scene that was so richly composed I would have been happy to call any of them my garden. I was particularly interested in learning about Gahnia, a New Zealand sedge genus that was new to me and nearly unknown in cultivation. Gordon and I confirmed the identity of the gracefully mounded plant at center and in the distance as mountain cutty grass, G. procera. Growing nearby we noted golden trailing Podocarpus nivalis, spiky, dark red-brown Dracophyllum, silvery Celmisia incana, southern beech Noth-ofagus solanderi, and many others at home in the same habitat. New Zealand gardeners and nursery professionals are now bringing Gahnia species into cultivation and recognizing them for the beauty they bring to the country’s regional landscapes.

A project for the Delaware Department of Transportation has given me the chance to look more closely at this small state’s grasses. The purpose of the project, Enhancing Delaware Highways, is to celebrate the beauty and diversity of Delaware’s flora in the design and management of its roadside landscapes. The southernmost of the state’s three counties, Sussex, is on the outer coastal plain and is naturally sandy and droughty. While working with medians and dune edges near the town of Dewey, I noticed that naturally occurring coastal switchgrass, Panicum amarum, easily withstood the often challenging conditions, and that the local population included some strikingly blue foliage forms. Although this species is recognized for its value in dune stabilization it was not part of the garden palette at the time. I worked with Dale Hendricks and North Creek Nurseries to collect seed, run trials, and select a particularly blue plant to be introduced as a vegetatively propagated cultivar, ‘Dewey Blue’. In a few years this plant has become available to gardeners and landscape architects working with similar droughty conditions. The name commemorates the place of origin, and the cultivar helps point to the appeal and utility of a species formerly ignored.

Panicum amarum ‘Dewey Blue’ in the author’s Pennsylvania garden.

Production rows at Hoffman Nursery in Rougemont, North Carolina, represent two continents and one trend. Muhlenbergia capillaris (foreground) is an up-and-coming southeastern North American species, while Miscanthus sinensis (background) is a tried-and-true crop that hails from eastern Asia. In many parts of North America Miscanthus poses no threat to regional ecologies, due to naturally limiting factors such as aridity or cold. In the warm, moist Southeast, M. sinensis has demonstrated its potential for disrupting relatively intact habitats, and the future of prolific seeding types is uncertain. John Hoffman and his crew are taking progressive steps to identify and produce grasses such as Muhlenbergia and Panicum, which offer environmentally responsible alternatives for the Southeast.

Karl Partsch’s selection of tall moor grass, Molinia caerulea subsp. arundinacea ‘Zuneigung’, arches gracefully above red roses in the Sichtungsgarten (study garden) in Weihenstephan, Germany. Partsch is a naturalist, not a nurseryman; however, he has a keen eye and the variations he’s found on his treks through world habitats have many times enriched the diversity of garden grasses. He selected ‘Zuneigung’ for its form, which becomes increasingly relaxed and spreading as the flowering stems bend under the weight of maturing seeds.

Grasses at the Edge

The majority of the world’s grasses and their close relatives the sedges, rushes, restios, and cattails are still at the very edge of our garden vision, yet they hold the promise of great beauty and utility for landscapes we have yet to discover, yet to recognize, yet to imagine. They are sure to play increasingly greater roles as we move toward a design ethic that embraces transitions through space and time, palette and purpose, meaning and motivation.

Salt hay, Spartina patens, and smooth cordgrass, S. alterniflora, define the edge of a saltmarsh in Orleans, on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, as the sun appears improbably through a driving snowstorm five days before the new year. A path between the wooded bluff and the water has been worn by walkers, and its line is adjusted each season in response to the tides. Every year in August, sea lavender, Limonium nashii, blooms among the grasses’ summer greens. This local landscape is revered and gently tended, which in my estimation makes it fit for inclusion in what we call “the garden.”

Corn meets the mountains in western Pennsylvania in October. Credible as art, it is merely agriculture.