Date: From 1961 to 1975

Definition: Late twentieth century conflict between U.S.-backed South Vietnam and communist North Vietnam-supported rebels known as the Viet Cong.

Significance: The Vietnam War was one of the most contentious wars in the United States’ history. Due to heavy jungle terrain, the U.S. Air Force played an especially important role in U.S. military operations in the region.

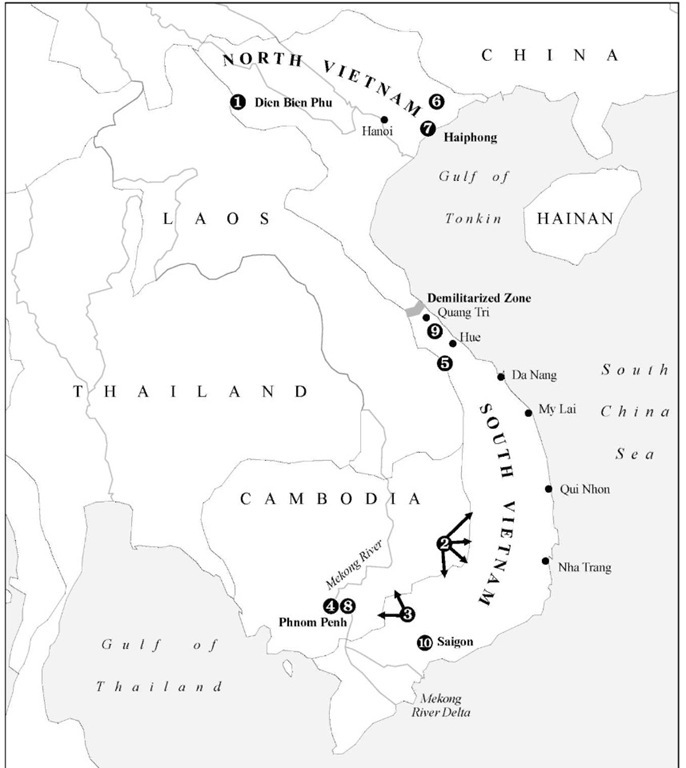

Vietnam Conflict, 1954-1975

(1) France falls, 1954. (2) Tet Offensive, January, 1968. (3) Cambodian invasion, April-May, 1970. (4) Sihanouk falls, April, 1970. (5) Laotian incursion, February, 1971. (6) Areas of U.S. bombing, 1972. (7) Mining of Haiphong Harbor, May, 1972. (8)LonNol falls, April, 1975. (9) North Vietnamese offensive, spring, 1975. (10) South Vietnam surrenders, April 30, 1975.

Background

The air war in South Vietnam had been in continuous operation before the United States entered the conflict. The U.S. Air Force had been participating in a low-key manner in Vietnam since 1956, actively training and equipping special combat units to deal with counterinsurgency warfare, long before President Lyndon Johnson set the United States upon a course of conflict in that region. It was not until the South Vietnamese government was no longer able to handle their situation that the U.S. presence was increased. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution gave the president tacit approval to take whatever action in the region he felt necessary. One such action was to wage major air operations into both North and South Vietnam. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August, 1964, the U.S. Air Force began armed reconnaissance missions from Thailand and South Vietnam.

Early Combat

The types of aircraft available for air combat in Southeast Asia in the 1960′s included transports, fighters and fighter-bombers, bombers, and reconnaissance aircraft. Among the transports were World War Il-era C-47′s, C-119′s from the mid-1950′s, C-7 Caribous, C-124′s, and C-130A’s and C-130B’s. Eventually, the C-141A replaced the C-124′s. The first three were used in-country, whereas the latter were used to transport heavy equipment and large numbers of personnel over longer distances.

Among the U.S. Air Force’s fighters and fighter-bombers were A-lE’s and A-lH’s, large piston-engine attack aircraft of Korean War vintage. The F-100C Super Sabre, F-102A Dagger, F-104A Starfighter, and the F-105D Thunderchief were also available. The F-102 and F-104, ineffective for this type of war, were removed after a few months in the theater. The F-105 was the Air Force’s only deep-strike fighter-bomber, and the F-100 was its predecessor. The U.S. Navy aircraft included the F-8U Crusader (renamed the A-4D during this period), the AD (the same craft as the U.S. Air Force A-1H), and the F4H-1 Phantom (renamed the F-4B during this period). The A-4D was a small, single-engine, single-place attack aircraft. The F-8U was an air-to-air fighter. The F-4B Phantom replaced the F-8.

Bomber aircraft included B-26′s (formerly A-26′s from World War II), B-57 Canberras, and B-52D’s. The B-52 was used over South Vietnam between 1965 and 1972. The B-57′s were used until they were replaced by units of new Air Force F-4C’s. The B-26 was used in counterinsurgency roles.

RF-101′s and RA-5J’s served as reconnaissance aircraft. Later in the air war, the RF-4C replaced the almost-depleted inventory of RF-101′s.

Numerous air bases in South Vietnam and Thailand supported these aircraft. The bases supporting air strikes against North Vietnam were large; Danang was located on South Vietnam’s northeast coast, and Takhli and Korat were located in Thailand. Operations out of Thailand were kept secret until Time magazine broke the story in the winter of 1966.

On February 7, 1965, the U.S. base at Pleiku was attacked by mortar rounds and enemy demolition teams; the damage was fairly extensive. Twenty aircraft were destroyed, and there were a number of American casualties. This attack gave the Johnson war team the excuse to launch the next and more extensive phases of the air campaign. Until this time, missions had consisted only of armed reconnaissance in the lower regions of North Vietnam, with some strikes by the U.S. Navy on coastal targets further north. In addition, other Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) actions made it clear that Hanoi was not going to back down against the limited bombing campaign.

Soon thereafter, U.S. secretary of defense Robert McNamara announced that the United States was bombing North Vietnam for three reasons: to retaliate for the bombing of U.S. and South Vietnamese bases; to prevent the North from supplying the VC in the south; and to improve the morale of the South Vietnamese Army. McNamara made no mention of defeating the North Vietnamese by destroying their war-making capacity. On March 2, 1965, Operation Rolling Thunder began in earnest and would become the air campaign that President Johnson used to punish the enemy and retaliate for North Vietnamese aggression.

Operation Rolling Thunder

Operation Rolling Thunder was a stratagem of the National Security Council, the president’s key advisers on the Vietnam War. The campaign was a follow-up for the failure of a plan to keep the pressure on the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese without increasing the commitment of U.S. combat personnel. Early Rolling Thunder missions involved both the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy. Targets were primarily those of interdiction, blocking the routes, known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, by which the North Vietnamese moved personnel and supplies into South Vietnam. Suspected storage areas were also targeted. U.S. Air Force fighter-bombers and U.S. Navy attack aircraft were the principle means of carrying out missions of interdiction.

The F-105D, the only U.S. Air Force deep-strike fighter-bomber, was well suited for the job of carrying out missions against North Vietnam. The U.S. Navy had always used its attack aircraft for coastal operations, and the A-4 was the preferred attack aircraft. The F-4 was the other fighter-bomber used by both the Navy and Air Force in this role. Because the Air Force F-105 had the speed and pay-load suited for hitting targets deep within North Vietnam, it flew 85 percent of the bombing sorties over the region between 1965 and 1969.

In 1965, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, under the direction of the president, had placed a restricted no-bombing area around Hanoi and Haiphong, a heavily defended region of western North Vietnam where mountains could shield large strike forces from surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and multiple-gun emplacements. However, strike aircraft faced a problem in getting safely to any target near Hanoi. The route most often used was to refuel off tankers in northern Thailand and then proceed over northern Laos and turn in over the Red River where it came out from the mountains. This route took advantage of a ridgeline that ran from the northwest directly toward Hanoi, which helped to shield the flights from the radar and SAMs. Where the ridge ended, the attack aircraft would have a shorter run toward the highly defended targets around Hanoi. This ridge was named Thud Ridge, for it was there that most missions made ingress to Hanoi, and many F-105′s were lost in this area.

Air Operations in the South

While Operation Rolling Thunder was conducted over North Vietnam, air combat operations were flown over South Vietnam in support of the ground operations. Close air support (CAS) missions were those in which fighter-bomber and attack aircraft were directed by ground controllers or airborne forward air controllers (FACs). Thousands of such vital missions were flown by the Air Force, Navy, and Marines in support of both U.S. and South Vietnamese troops engaged with VC or NVA regulars.

The first use of a strategic “nuclear” bomber, the B-52, was against suspected enemy troop areas in South Vietnam. The B-52D was modified to carry 500- to 1,000-pound high-explosive bombs. One aircraft could carry 150 tons of bombs. The early B-52 missions, called Arc Light, were controlled not from Saigon but from Strategic Air Command Headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska.

Escalation

President Johnson and his advisers had expected that Operation Rolling Thunder would pressure the North Vietnamese into negotiating a settlement and pulling back from their support of the civil war in South Vietnam. However, it was clear to many in combat that the U.S. show of force would be insufficient unless it was aimed at targets that would cripple the economy of the north. In June, 1965, there were seven known and occupied, but untargeted, SAM sites ringing Hanoi. By the end of 1966, North Vietnam had more than 150 SA-2 SAM sites. Although the first U.S. strikes against SA-2 sites were difficult and ineffective, the arrival of the modified two-seat F-105′s allowed U.S. forces to reduce significantly the effectiveness of the SAMs.

In November, 1965, the end of the first period of F-105 involvement was marked by the arrival of more F-105′s from the United States. Aircraft that had been on nuclear alert were moved to Southeast Asia, thus severely depleting the capability of the Fifth Air Force in Japan to counter any threats in that region.

In the first year of Rolling Thunder, an average of two large strikes per week would be authorized by the Joint Chiefs of Staff against targets in the Hanoi area. The need to hit industrial targets was recognized by the air war planners. Railroads in the north were added to the target list and a new target, oil storage, was finally approved in the spring of 1966. The first large-scale strike, on oil storage sites southeast of Hanoi on June 29,1966, was a success. Eight F-105′s from Korat and sixteen from Takhli were the Air Force strike package that day. A strike package of A-4′s from the U.S. Navy also participated. Only one aircraft was lost and the pilot bailed out over Hanoi. Further raids against POL (oil) storage sites were flown. Soon the North Vietnamese were dispersing their oil in drums around the country.

Throughout 1965 and 1966, the U.S. forces refrained from bombing major enemy air bases. The appearance of enemy Mig-17′s and Mig-21′s was rare. American aircrews knew that if they were attacked from the air and had to jettison their heavy bomb loads, the enemy pilots would have accomplished their primary mission. All F-105 Mig kills were made with guns. F-105′s shot down twenty-seven enemy fighters during the air campaigns. The F-4 was limited to air-to-air heat-seeking missiles (AIM-9′s) and radar missiles (AIM-7′s).

In 1966, the Joint Chiefs of Staff gained presidential approval to hit an additional eleven industrial targets. In the meantime, Secretary McNamara, losing faith in Rolling Thunder, issued directives that reduced the number of missions flown by any one squadron from twenty to sixteen per day. Flight leaders knew that their tactics might be negated by North Vietnamese countermeasures in the heavily defended Route Pack 6 region. Even with the incorporation of better SAM-warning devices and new QRC-160 jamming pods, the F-105 pilots faced difficulty in penetrating Hanoi’s defenses.

Linebacker I and II

Historians have not fully accepted that by 1968 the ground war in South Vietnam was turning in favor of the allied forces. In February, 1968, the enemy mounted an offensive during the Tet holiday that shocked the American public and cast into doubt the U.S. strategy. Although the worst fighting centered on the South Vietnamese coastal town of Hue, VC and NVA units had sprung up throughout South Vietnam. It was not known until years later that this battle was a result of desperation on the part of the enemy. Their tactics failed, but their strategy worked: On March 31, 1968, Johnson announced that he would not run for another term in office, and on October 31,1968, the last Rolling Thunder mission was flown. From November of that year through the winter of 1972, air combat operations in South Vietnam continued even as U.S. troop strengths were being reduced.

Finally, after years of fruitless negotiations and diplomatic moves, President Richard M. Nixon authorized resumed bombing over North Vietnam. By then, there were some newer weapons on hand. The Air Force attempted to fly F-105′s over North Vietnam at night and in bad weather, but this mission, nicknamed “Ryan’s Raiders,” was a failure. The Navy and Marine Corps were more successful with the new A-6 Intruder, which could deliver bombs in limited visibility with its improved radar and computerized bomb systems. The question to be answered was how to bring the full power of the U.S. air arm to bear upon North Vietnam. That was done with a massive buildup of fighter-bombers and, later,B-52′s.

Linebacker I was designed to hit North Vietnam’s industrial sites. Hanoi and Haiphong were no longer off limits. The harbor of Haiphong was mined. In effect, the Joint Chiefs of Staff won its argument that the air war had been shackled to the concept of gradual escalation and that the United States had been unable to unleash the air power at its disposal.

The North Vietnamese government began to respond to this new phase of the air war. It was, however, an exhausting campaign for the pilots of fighter-bombers and supporting aircraft. After the Paris peace talks stalled in the fall of 1972, the U.S. government further escalated the bombing campaign. Under Linebacker II, B-52′s began bombing the Hanoi area every night. At first, the bombers came over the area in trail and the SA-2 batteries discovered a break in the jamming through which they could target some of the bombers. Losses were high. It was not until the Strategic Air Command authorized the local commanders at U Ta Pao and Guam to work their own tactics that the North Vietnamese were defeated in their defenses.

This last bombing campaign lasted slightly more than two weeks, and by the end of December, 1972, agreement had been reached to release all prisoners of war and to bring a cease-fire to South Vietnam. It was the chance for the United States to pull out of the Vietnam debacle. No one trusted that the cease-fire would last, but there was hope that the South Vietnamese government was strong enough to defend itself.

During the air war over Vietnam, the United States learned many military lessons, some of which led to a complete revamping of both Air Force and Navy combat operations. New aircraft with much greater capabilities were developed and acquired, and new smart bombs were placed into the U.S. arsenal. However, the greatest lesson learned, which carried over into the development of weapons and tactics that were used nearly two decades later, was that seven years of escalation and bombing on a reduced level had been insufficient to end the Communist-driven civil war.