101. Arithmetic Average

The risk of an item is reflected in its variability from its average level. For comparison, a stock analyst may want to determine the level of return and the variability in returns for a number of assets to see whether investors in the higher risk assets earned a higher return over time. A financial analyst may want to examine historical differences between risk and profit on different types of new product introductions or projects undertaken in different countries.

If historical, or ex-post, data are known, an analyst can easily compute historical average return and risk measures. If Xt represents a data item for period t, the arithmetic average X, over n periods is given by:

n

EXt

X = .

n

In summary, the sum of the values observed divided by the total number of observation—some-times referred to as the mean.

103. ARM

Adjustable rate mortgage is a mortgage in which the contractual interest rate is tied to some index of interest rates (prime rate for example) and changes when supply and demand conditions change the underlying index.

104. Arrears

An overdue outstanding debt. In addition, we use arrearage to indicate the overdue payment.

105. Asian Option

An option in which the payoff at maturity depends upon an average of the asset prices over the life of the option.

106. Asian Tail

A reference price that is computed as an average of recent prices. For example, an equity-linked note may have a payoff based on the average daily stock price over the last 20 days (the Asian tail).

107. Ask Price

The price at which a dealer or market-maker offers to sell a security. Also called the offer price.

108. Asset Allocation Decision

Choosing among broad asset classes such as stocks versus bonds. In other words, asset allocation is an approach to investing that focuses on determining the mixture of asset classes that is most likely to provide a combination to risk and expected return that is optimal for the investor. In addition to this, portfolio insurance is an asset-allocation or hedging strategy that allows the investor to alter the amount of risk he or she is willing to accept by giving up some return.

109. Asset Management Ratios

Asset management ratios (also called activity or asset utilization ratios) attempt to measure the efficiency with which a firm uses its assets.

Receivables Ratios

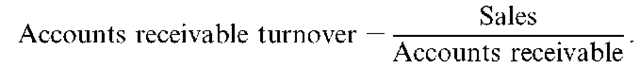

Accounts receivable turnover ratio is computed as credit sales divided by accounts receivable.In general, a higher accounts receivable turnover ratio suggests more frequent payment of receivables by customers. The accounts receivable turnover ratio is written as:

Thus, if a firm’s accounts receivable turnover ratio is larger than the industry average; this implies that the firm’s accounts receivable are more efficiently managed that the average firm in that industry.

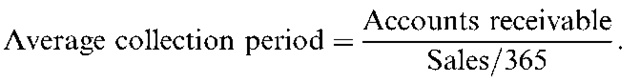

Dividing annual sales by 365 days gives a daily sales figure. Dividing accounts receivable by daily sales gives another asset management ratio, the average collection period of credit sales. In general, financial managers prefer shorter collection periods over longer periods.

Comparing the average collection period to the firm’s credit terms indicates whether customers are generally paying their accounts on time. The average collection period is given by:

The average collection period (ACP) is easy to calculate and can provide valuable information when compared to current credit terms or past trends.

One major drawback to the ACP calculation, however, is its sensitivity to changing patterns of sales. The calculated ACP rises with increases in sales and falls with decreases in sales. Thus, changes in the ACP may give a deceptive picture of a firm’s actual payment history. Firms with seasonal sales should be especially careful in analyzing accounts receivable patterns based on ACP. For instance, a constant ACP could hide a longer payment period if it coincides with a decrease in sales volume. In this case, the ACP calculation would fail to properly signal a deterioration in the collection of payments.

Inventory Ratios

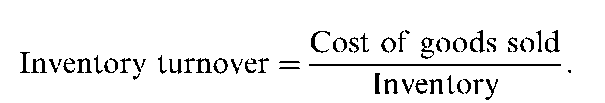

The inventory turnover ratio is a measure of how quickly the firm sells its inventory.It is computed as cost of goods sold divided by inventory. The ratio clearly depends upon the firm’s inventory accounting method: for example, last-in, first-out (LIFO) or first-in, first-out (FIFO). The inventory turnover ratio is written as:

It is an easy mistake to assume that higher inventory turnover is a favorable sign; it also may signal danger. An increasing inventory turnover may raise the possibility of costly stockouts. Empty shelves can lead to dissatisfied customers and lost sales.

Fixed and Total Assets Ratio

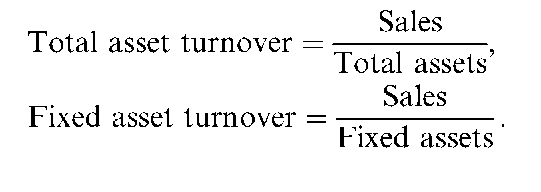

The total asset turnover ratio is computed as sales divided by total assets.The fixed asset turnover ratio is sales divided by fixed assets. Similar to the other turnover ratio, these ratios indicate the amount of sales generated by a dollar of total and fixed assets, respectively. Although managers generally favor higher fixed and total asset turnover ratios, these ratios can be too high. The fixed asset turnover ratio may be large as a result of the firm’s use of old, depreciated equipment. This would indicate that the firm’s reliance on old technology could hurt its future market position, or that it could face a large, imminent expense for new equipment, including the downtime required to install it and train workers.

A large total asset turnover ratio also can result from the use of old equipment. Or, it might indicate inadequate receivables arising from an overly strict credit system or dangerously low inventories.

The asset turnover ratios are computed as:

110. Asset Sensitive

A bank is classified as asset sensitive if its GAP is positive. Under this case interest rate sensitive asset is larger than interest rate sensitive liability.

111. Asset Swap

Effectively transforms an asset into an asset of another type, such as converting a fixed rate bond into a floating-rate bond. Results in what is known as a ”synthetic security.”

112. Asset Turnover (ATO)

The annual sales generated by each dollar of assets (sales/assets). It can also be called as asset utilization ratio.

113. Asset-Backed Debt Securities (ABS)

Issuers of credit have begun following the lead set by mortgage lenders by using asset securitization as a means of raising funds. Securitization meaning that the firm repackages its assets and sells them to the market.

In general, an ABS comes through certificates issued by a grantor trust, which also registers the security issue under the Securities Act of 1933. These securities are sold to investors through underwritten public offerings or private placements. Each certificate represents a fractional interest in one or more pools of assets. The selling firm transfers assets, with or without recourse, to the grantor trust, which is formed and owned by the investors, in exchange for the proceeds from the certificates. The trustee receives the operating cash flows from the assets and pays scheduled interest and principal payments to investors, servicing fees to the selling firm, and other expenses of the trust.

From a legal perspective, the trust owns the assets that underlie such securities. These assets will not be consolidated into the estate of the selling firm if it enters into bankruptcy.

To date, most ABS issues have securitized automobile and credit-card receivables. It is expected that this area will grow into other fields, such as computer leases, truck leases, land and property leases, mortgages on plant and equipment, and commercial loans.

114. Asset-Backed Security

A security with promised principal and interest payments backed or collateralized by cash flows originated from a portfolio of assets that generate the cash flows.

115. Asset-Based Financing

Financing in which the lender relies primarily on cash flows generated by the asset financed to repay the loan.

116. Asset-Liability Management

The management of a bank’s entire balance sheet to achieve desired risk-return objectives and to maximize the market value of stockholders’ equity. Asset-liability management is the management of the net interest margin to ensure that its level and riskness are compatible with risk/return objectives of the institution.

117. Asset-or-Nothing Call

An option that pays a unit of the asset if the asset price exceeds the strike price at expiration or zero otherwise.

118. Asset-or-Nothing Option

An option that pays a unit of the asset if the option is in-the-money or zero otherwise.

119. Assets

Anything that the firm owns. It includes current, fixed and other assets. Asset can also be classified as tangible and intangible assets.

120. Assets Requirements

A common element of a financial plan that describes projected capital spending and the proposed uses of net working capital. Asset requirements increase when sales increase.

121. Assignment

The transfer of the legal right or interest on an asset to another party.

122. Assumable Mortgage

The mortgage contract is transferred from the seller to the buyer of the house.

123. Asymmetric Butterfly Spread

A butterfly spread in which the distance between strike prices is not equal. [See also Butterfly spread]

125. At The Money

The owner of a put or call is not obligated to carry out the specified transaction but has the option of doing so. If the transaction is carried out, it is said to have been exercised. At the money means that the stock price is trading at the exercise price of the option.

126. Auction Market

A market where all traders in a certain good meet at one place to buy or sell and asset. The NYSE is an example for stock auction market.

127. Audit, or Control, Phase of Capital Budgeting Process

The audit, or control, phase is the final step of the capital budgeting process for approved projects. In this phase, the analyst tracks the magnitude and timing of expenditures while the project is progressing. A major portion of this phase is the post-audit of the project, through which past decisions are evaluated for the benefit of future project analyses.

Many firms review spending during the control phase of approved projects. Quarterly reports often are required in which the manager overseeing the project summarizes spending to date, compares it to budgeted amounts, and explains differences between the two. Such oversight during this implementation stage slows top managers to foresee cost overruns. Some firms require projects that are expected to exceed their budgets by a certain dollar amount or percentage to file new appropriation requests to secure the additional funds. Implementation audits allow managers to learn about potential trouble areas so future proposals can account for them in their initial analysis. Implementation audits generally also provide top management with information on which managers generally provide the most accurate estimates of project costs.

In addition to implementation costs, firms also should compare forecasted cash flows to actual performance after the project has been completed. This analysis provides data regarding the accuracy over time of cash flow forecasts, which will permit the firm to discover what went right with the project, what went wrong, and why. Audits force management to discover and justify any major deviations of actual performance from forecasted performance. Specific reasons for deviations from the budget are needed for the experience to be helpful to all involved. Such a system also helps to control intra-firm agency problems by helping to reduce ”padding” (i.e., overestimating the benefits of favorite or convenient project proposals). This increases the incentives for department heads to manage in ways that will help the firm achieve its goals.

Investment decisions are based on estimates of cash flows and relevant costs, while in some firms the post-audit is based on accrued accounting and assigned overhead concepts. The result is that managers make decisions based on cash flow, while they are evaluated by an accounting-based system.

A concept that appears to help correct this evaluation system problem is economic value added (EVA).

The control or post-audit phase sometimes requires the firm to consider terminating or abandoning an approved project. The possibility of abandoning an investment prior to the end of its estimated useful or economic life expands the options available to management and reduces the risk associated with decisions based on holding an asset to the end of its economic life. This form of contingency planning gives decision makers a second chance when dealing with the economic and political uncertainties of the future.

128. Audits of Project Cash Flow Estimated

Capital budgeting audits can help the firm learn from experience. By comparing actual and estimated cash flows, the firm can try to improve upon areas in which forecasting accuracy is poor.

In a survey conducted in the late 1980s, researchers found that three-fourths of the responding Fortune 500 firms audited their cash flow estimates. Nearly all of the firms that performed audits compared initial investment outlay estimates with actual costs; all evaluated operating cash flow estimates; and two-thirds audited salvage-value estimates. About two-thirds of the firms that performed audits claimed that actual initial investment outlay estimates usually were within 10 percent of forecasts. Only 43 percent of the firms that performed audits could make the same claim with respect to operating cash flows. Over 30 percent of the firms confessed that operating cash flow estimates differed from actual performance by 16 percent or more. This helps to illustrate that our cash flow estimates are merely point estimates of a random variable. Because of their uncertainty, they may take on higher or lower values than their estimated value.

To be successful, the cash flow estimation process requires a commitment by the corporation and its top policy-setting managers; this commitment includes the type of management information system the firm uses to support the estimation process. Past experience in estimating cash flows, requiring cash flow estimates for all projects, and maintaining systematic approaches to cash flow estimation appear to help firms achieve success in accurately forecasting cash flows.

129. Autocorrelation

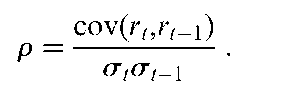

The correlation of a variable with itself over successive time intervals. The correlation coefficient can be defined as:

It can be defined as where cov(rt, rt_ 1) is the cov-ariance between rt, rt_1,st and st_1 are standard deviation rt and rt_1, respectively.

Two useful empirical examples of autocorrelation are:

Interest rates exhibit mean reversion behavior and are often negatively auto correlated (i.e., an up move one day will suggest a down move the next). But note that mean reversion does not technically necessitate negative autocorrelation.

Agency credit ratings typically exhibit move persistence behavior and are positively auto correlated during downgrades (i.e., a downgrade will suggest another downgrade soon). But, for completeness, note that upgrades do not better predict future upgrades.

130. Automated Clearing House System (ACH)

An Automated Clearing House (ACH) system is an information transfer network that joins banks or other financial institutions together to facilitate the transfer of cash balances. An ACH system has a high initial fixed cost to install but requires a very low variable cost to process each transaction. The

Federal Reserve operates the nation’s primary ACH, which is owned by the member banks of the Federal Reserve System. Most banks are members of an ACH.

Instead of transferring information about payments or receipts via paper documents like checks, an ACH transfers the information electronically via a computer.

131. Automated Clearinghouse

A facility that processes interbank debits and credits electronically.

132. Automated Loan Machine

A machine that serves as a computer terminal and allows a customer to apply for a loan and, if approved, automatically deposits proceeds into an account designated by the customer.

133. Automated Teller Machines (ATM)

The globalization of automated teller machines (ATMs) is one of the newer frontiers for expansion for US financial networks. The current system combines a number of worldwide communication switching networks, each one owned by a different bank or group of banks.

A global ATM network works like a computerized constellation of switches. Each separate bank is part of a regional, national, and international financial system.

After the customer inserts a credit card, punches a personal identification number (PIN), and enters a transaction request, the bank’s computer determines that the card is not one of its own credit cards and switches the transaction to a national computer system. The national system, in turn, determines that the card is not one of its own, so it switches to an international network, which routes the request to the US Global Switching Center. The center passes the request to a regional computer system in the US, which evaluates the request and responds through the switching network. The entire time required for this process, from initiation at the ATM until the response is received, is reassured in seconds. The use, acceptance, and growth of systems like this will revolutionize the way international payments are made well into the 21st century.

134. Availability Float

It refers to the time required to clear a check through the banking system. This process takes place by using either Fed-check collection services, corresponding banks or local clearing houses.

135. Average Accounting Return (AAR)

The average project earnings after taxes and depreciation divided by the average book value of the investment during its life. [See also Accounting rate of return]

136. Average Annual Yield

A method to calculate interest that incorrectly combines simple interest and compound interest concepts on investments of more than one year. For example, suppose you invested $10,000 in a five-year CD offering 9.5 percent interest compounded quarterly, you would have $15,991.10 in the account at the end of five years. Dividing your $5,991.10 total return by five, the average annual return will be 11.98 percent.

137. Average Collection Period

Average amount of time required to collect an accounting receivable. Also referred to as days sales outstanding. [See also Asset management ratios and Activity ratios]

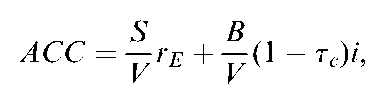

138. Average Cost of Capital

A firm’s required payout to the bondholders and the stockholders expressed as a percentage of capital contributed to the firm. Average cost of capital is computed by dividing the total required cost of capital by the total amount of contributed capital. Average cost of capital (ACC) formula can be defined as:

where V = total market value of the firm; S = value of stockholder’s equity; B = value of debt; rE = rate of return of stockholder’s equity; i = interest rate on debt; and tc = corporate tax rate.

Here, rE is the cost of equity, and (1 — tc)i is the cost of debt. Hence, ACC is a weighted average of these two costs, with respective weights S/Vand B/V.

139. Average Daily Sales

Annual sales divided by 365 days.

140. Average Exposure

Credit exposure arising from market-driven instruments will have an ever-changing market-to-market exposure amount. The average exposure represents the average of several expected exposure values calculated at different forward points over the life of swap starting from the end of the first year. The expected exposures are weighted by the appropriate discount factors for this average calculation.

141. Average Price Call Option

The payoff of average price call option = max [0, A(T) — K], where A(T) is the arithmetic average of stock price over time and K is the strike price. This implies that the payoff of this option is either equal to zero or larger than zero. In other words, the amount of payoff is equal to the difference between A(T) and K.

142. Average Price Put Option

The payoff of average price put option = max [0, K — A(T)], where A(T) is the arithmetic average of stock price per share over time and K is the strike price. This implies that the payoff of this option is either equal to zero or larger than zero. In other words, the amount of payoff is equal to the difference between K and A(T).

143. Average Shortfall

The expected loss given that a loss occurs, or as the expected loss given that losses exceed a given level.

144. Average Strike Option

An option that provides a payoff dependent on the difference between the final asset price and

the average asset price. For example, an average strike call = max[0, ST— A(T)], where A(T) represents average stock price per share over time and ST represents stock price per share in period T.

145. Average Tax Rate

The average tax rate is the tax bill of a firm divided by its earnings before income taxes (i.e., pretax income). For individuals, it is their tax bill divided by their taxable income. In either case, it represents the percentage of total taxable income that is paid in taxes.