Editing is to cutting as architecture is to bricklaying—one is an art; the other is a craft. Not all architects are brilliant, nor is all architecture high art, but at its best it is undeniably creative. So is editing. In the realm of film, however, the "architect" may also be the "bricklayer" or, more properly, vice versa: The cutter may be the editor, but not necessarily so.

It must be understood that the editing or reediting of a film is not always standard procedure. Some scripts are well written, and minor changes, if any, are made during production. Scenes are well staged, well acted, and well shot. The cutter’s job is then relatively simple; he needs only to join the relevant portions of the selected takes together in the most efficient and properly paced manner.

In a fair percentage of cases, however, it is not quite that easy and not nearly so straightforward. Especially on the more ambitious projects, problems, not always unforeseen, will arise. Films such as Reds, Lawrence of Arabia, Gone With the Wind, Dr. Zhivago, or my own The Young Lions carry such complex plots and are inhabited by so many characters that intelligent story decisions cannot always be made at the script stage or even at the shooting stage. Some scenes may be shot "on spec," and the final judgment as to their worth may be deferred until after the first cut has been viewed. Then the work begins. It is by no means unusual for that work to take two, three, or even four times as long as the actual shooting.

When deletion starts, the speculative scenes or sequencer are not always the first to go. Contributions of the director and/or the actors may have changed values, relative importance, or even story direction during the course of photography. Even everybody’s favorite scene (in the script) may turn out to be expendable on the screen. An opening scene, for instance, written for purely expository purposes, may turn out to be redundant if the characters, due to brilliant interpretation on the set, have been more fully developed throughout the film than they had originally been visualized. Or, not infrequently, a realignment of a scene may help to clarify a circuitous plot or a fuzzy character.

All this is not too different from the contribution of a literary editor whose authors have a leaning toward long-winded-ness.* But there is one marked dissimilarity. Film is not as malleable or as cheap as print. If a segment of a novel is deleted, a sentence or two may be all that is needed to fashion a proper bridge or transition, ha films, the equivalent of that sentence or two will probably not have been shot, and retakes or added scenes cost many thousands of dollars. The saving of those thousands of dollars can sometimes be accomplished by the application of some ingenuity, at the least, or creativity, at best. Let us now consider a few examples of the different types of "editing," as opposed to "cutting," that may be required.

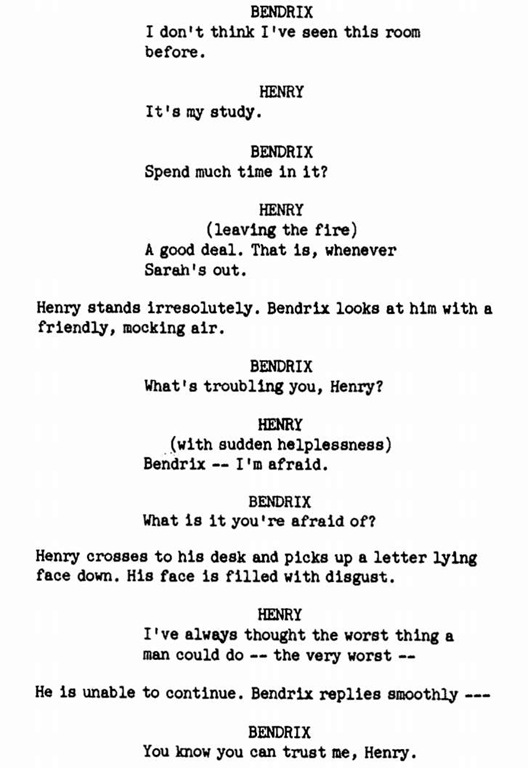

The first example is a segment from the early pages of The End of the Affair, Lenore Coffee’s screenplay of the novel by Graham Greene. The changes in this short scene do not result in any measurable shortening of its length, and the material was all at hand from the original shooting. However, since the continuity was now altered, special care had to be taken to ensure a smooth, non-contradictory flow of images.

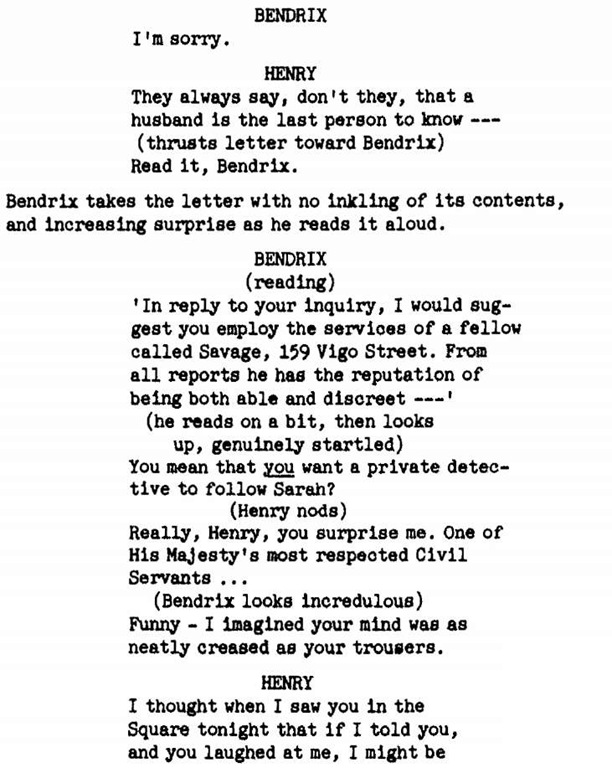

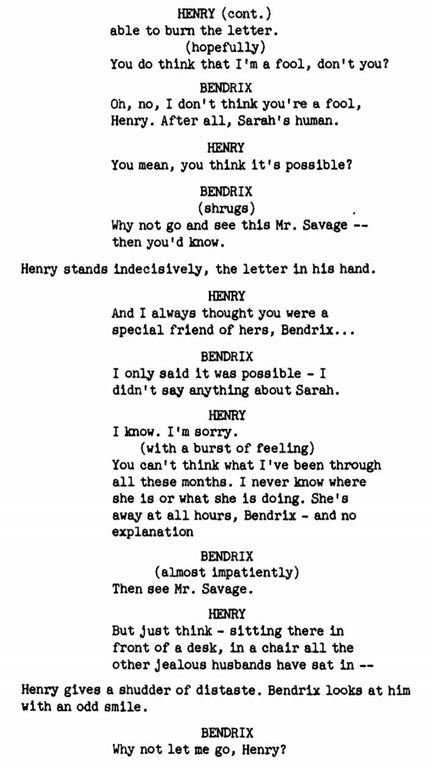

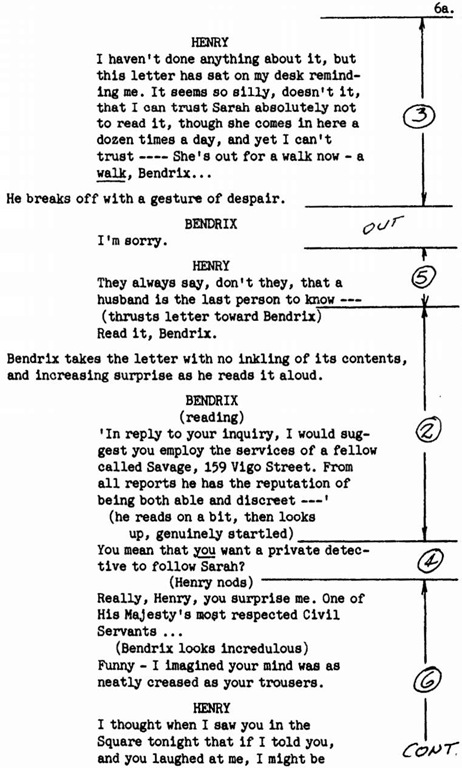

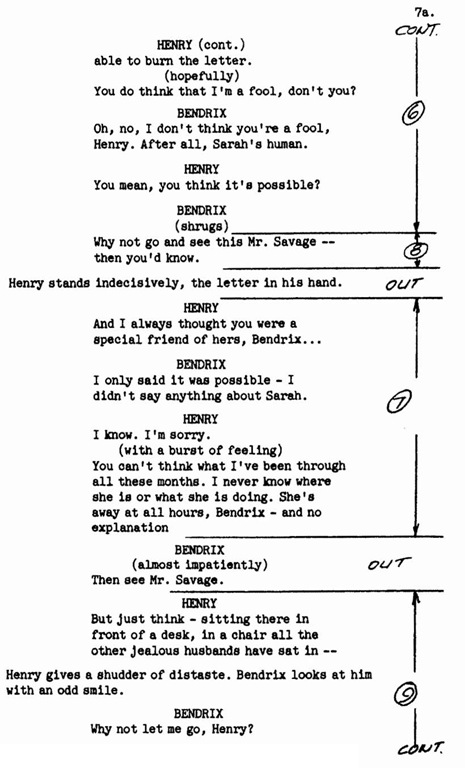

Figure 9 shows the scene as it appeared in the shooting script. (It will be noted that it was written as a master scene.) Figure 10 shows the same pages marked out for the new alignment; i.e., the sections which follow each other are designated (1), (2), (3), etc. Figure 11 presents the rearranged scene, with the cuts that made the rearrangement possible now indicated in script terms. The apparent increase in length is due to the insertion of the angle descriptions. In reality, the scene was shortened by a few seconds, but that was not the purpose of the changes.

First, study Figure 9.

Then, study the changes as indicated in Figure 10.

Since the purposes of the changes are by no means clearly evident on even careful examination, a rationalization is in order.

This operation is needed to allow more give and take in the dialogue, to eliminate the image of Henry standing dumbly (and unnaturally) while Bendrix ambles through his lines, his reactions, and his transitions, and to camouflage the expository nature of the last part of Bendrix’s speech (6).

Now, the rationalization in detail:

It quite satisfactorily establishes the tension for the moments that follow.

As it stands in the original, Bendrix takes Henry’s line (3) in stride ("I’m sorry"), as if he knows exactly what Henry is talking about. As far as the viewer is concerned, of course, he does not. We find out as the scene progresses that Henry’s only purpose in bringing Bendrix into his home is to discuss with him the letter and the situation which gave it birth. To show Henry behaving like a bashful schoolboy before getting to the point works against the character.

Instead, the new alignment allows us to understand, as Bendrix reads the opening paragraph of the letter, what Henry has on his mind. Now speech (3) has an altogether different thrust. It is no longer a puzzling circumlocution, but rather a somewhat indirect allusion to the reason for the letter’s intent; he mistrusts his wife—and it hurts.

HENRY’S STUDY

As Henry comes In he pokes up the fire until it burns brightly. It is a quiet, studious room, with leather chairs and a great many uniform volumes of topics on the shelves and an oil painting or two. Bendrix comes in and stands looking about the room.

Figure 10

HENRY

I haven’t done anything about it, but this letter has eat on my desk reminding me. It seeraa so silly, doesn’t it, that I can trust Sarah absolutely not to read It, though she comes In here a dozen times a day, and yet I can’t trust—-She’ s out for a walk now – a walk, Bendrix…

He breaks off with a gesture of despair.

Figure 10

Figure 10

HENRY’S STUDY

As Henry comes In he pokes up the fire until it bums brightly. It Is a quiet, studious room, with leather chairs and a great many uniform volumes of topics on the shelves and an oil painting or two. Bendrix comes in and stands looking about the room.

As Henry comes In he pokes up the fire until it bums brightly. It Is a quiet, studious room, with leather chairs and a great many uniform volumes of topics on the shelves and an oil painting or two. Bendrix comes in and stands looking about the room.

Figure 10

Figure 10

Figure 10

As a consequence, Bendrix’s next line (4) does not seem so gratuitous. Even though the line is a question, he is not guessing, but making a positive comment.

Line (5) is a further development of Henry’s sense of guilt and impropriety; again, not arbitrarily made, but in shamed answer to Bendrix’s attacking question.

Now (in 6) Bendrix has had time to put his thoughts, reactions, and emotions into place, and he continues the scene with a mocking chiding of Henry—a chiding that is really expository. But though the line tells us a good deal about Henry, its expository nature is concealed by its more apparent purpose—a gentle put-down and a quick puncturing of Henry’s mounting self-pity. As Henry’s answer indicates, this is exactly what he has been looking for as a way out of a degrading situation. It also gets the conversation back to a more hopeful direction (for Henry), only to have him jolted once more by Bendrix’s cynicism ("After all, Sarah’s human").

The third purpose of the realignment is to eliminate Bendrix’s "impatient" urging. Too much insistence on his part should make Henry suspicious, something both we and Bendrix are clever enough to avoid.

Figure 11 should now be read through nonclinically in order to absorb the flow of the realigned scene. At first reading the effect of the changes may seem slight, but as indicated in the foregoing paragraphs, they have considerable bearing on the believability of the scene and on the honesty of the characters in it.