INTRODUCTION

A learning style, or cognitive preference, is a consistent way of responding to and using stimuli in the context of learning. We can learn in many different ways, but when we use our preferred methods, we are generally at our best and feel most competent, natural, and energetic. There are many theories and various instruments to determine learning styles, but they are all essentially based on the idea that individuals perceive, organize, or process information differently on the basis of either learned or inherited traits. The related theory of multiple intelligences, introduced by Gardner (1983), states that every individual has a different set of developed intelligences, determining how easy or difficult it is to learn information presented in a particular manner. This can be seen as defining a specific learning style, although some authors (Silver, Strong, & Perini, 2000) claim that the multiple intelligences theory is centered around the content of learning in distinct fields of knowledge, while learning styles focus mostly on the process of learning.

This article presents an overview on learning styles and multiple intelligences, providing some historical context and presenting most relevant learning styles in different categories, focusing on perceptual and sensory modalities, ways of processing information, personality models, and personal talents. It also refers to the purpose and methods of knowing and identifying learning styles, and ways of supporting them in learning environments.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The tendency to typify human differences has a long tradition in history, and the number four has often appeared in the taxonomies (Silver et al., 2000). From the ancient Greeks to the Renaissance, the dominant concept of human personality was that of Hippocrates’ humors, based on the idea that everyone has four liquids or humors in the body: blood, black bile, phlegm, and yellow bile. A similar amount of each humor would result in a balanced human, while an excess of any of them would develop into one of the four types of personality: sanguine, melancholic, phlegmatic, and choleric. The sacred medicine wheel, in the spiritual stories of the North American Indians, also refers to four human personality traits: wisdom, clarity of perception, introspection, and understanding of one’s emotions.

In the 1920s, Swiss psychologist Carl Jung (1921) differentiated human personalities in his theory described in Psychological Types. Jung observed that, when people’s minds are active, they are involved in one of two mental activities: perceiving, taking in information; or judging, organizing that information and coming to conclusions. He identified two opposite ways people perceive—sensation and intuition—and two opposite ways that people judge—thinking and feeling. The combination of these dimensions results in four mental processes. In addition, Jung observed that individuals tend to focus their energy and be energized more by either the external world of people, experience, and activity, or the internal world of ideas, memories, and emotions. He called these two orientations of energy extraversion and introversion. Combining the two different orientations to the world with the four mental processes, Jung described eight fundamental patterns of mental activity available to people. While these eight mental processes are available to and used by everyone, he believed that people are innately different in what they prefer: their dominant function. Based on his observations, Jung concluded that differences in behaviour result from people’s inborn tendencies to use their minds in different ways. As people act on these tendencies, they develop patterns of behaviour: psychological types (Jung, 1961/1989; Myers, 2000).

Since the mid-1940s, there have been several influences contributing to the emergence of different models of learning styles, many of which were influenced by the Jungian theory on psychological types. A large number of researchers working in relative isolation have generated an extensive list of style labels. However, a careful examination of these lists discovers similarities that help to simplify and group concepts.

Defining intelligence is an endeavour that has long been the concern of the human kind (Silver et al., 2000). In ancient Greece, Plato believed that one could only be considered intelligent by being aware of one’s ignorance, and could only approach the understanding of an insignificant abstraction of a much larger and perfect truth, mostly through the study of geometry and logic. Aristotle disagreed with his teacher. For him, instead of a search for unattainable ideals, the act of gathering information was a venture of the human soul. He believed that humans were capable of two great mental abilities: quickly understanding causes and situations, and making good moral choices. Buddhist philosophy mentions three qualities of mind—wisdom, morality, and meditation—that guide humans to correctly view, think about, and act in the world. Christian philosophers in the MiddleAges tended to de-emphasise intelligence over faith and piety. Renaissance thinkers revalued human capacities of reason and creativity as forces capable of controlling and even remaking the world. The 20th century witnessed a considerable shift in the definition of intelligence, encompassing an increasing understanding of the human brain and its cognitive processes, including the theory on the brain’s hemispheres, the concept of emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1995), and the work carried out by neuroscientists like Damasio (1994). The theories of psychologists like Jean Piaget on how humans construct knowledge also played an important role in the understanding of the brain’s learning capacities. But, in spite of a more scientific and precise understanding ofhuman cognition, the concept of intelligence remains unclear. Psychometric indicators of intelligence, such as Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests, became widely accepted for some time. However, in recent years, Howard Gardner has been among those who have made pioneer breakthroughs in shattering the “fixed IQ” myth. The major fault with IQ tests is that they confuse logic with overall intelligence. Some tests also confuse linguistic ability with overall ability. Instead, Gardner defines intelligence as the capacity to solve problems or to create products that are valued in one or more cultural settings. We may recognize different types of intelligence in various fields and contexts. In spite of all these approaches and theories, the human mind still holds its mysteries that challenge our understanding and will inspire our research for years to come.

LEARNING STYLES

According to Conner and Hodgins (2002), learning styles come from three schools of thought:

• Perceptual Modality: biologically based reactions to the physical environment. It refers to the primary way our bodies take in information, such as auditory, visual, smell, kinesthetic, and tactile.

• Information Processing: distinguishes between the way we think, solve problems, and remember information. This may be thought of as the way we process information.

• Personality Models: refer to the way we interact with our surroundings, attention, emotions, and values.

Other authors (Theroux, 2002) differentiate perceptual (e.g., hemispheric dominance) from sensory models (e.g., VAK [visual, auditory, and kinesthetic]), and personality (e.g., Myers-Briggs) from personal talents (e.g., Gardner’s multiple intelligences). Anyway, regardless of natural learning preferences, it is important to recognize that some tasks and situational factors demand specialized learning modalities.

In this section, we present the most significant and referenced learning styles in the previous categories. Although multiple intelligences may also define learning styles, for their specific focus, they will be addressed in the next section.

Myers-Briggs

Katharine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Myers, added a fourth dimension to Jung’s psychological types based on Jung’s idea of the existence of an auxiliary function, in a kind of hierarchy of preference, resulting in 16 types indicated by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Myers, 2000), one of the most widely used personality survey instruments, researched and developed for more than 50 years. The four separate preference scales in the MBTI are (E)xtraversion – (I)ntroversion, (S)ensing – i(N)tuition, (T)hinking – (F)eeling, and (J)udging – (P)erceiving. Each preference is a multifaceted aspect of personality; however, it is the combination of the four preferences (e.g., INFJ) that provides the richest picture of each psychological type. Each preference also has some predictable effects on learning styles (Clark, 2000; Myers, 2000):

• Extraversion – Introversion: This indicates whether a learner finds energy in the external world of people and things, or in the internal world of concepts, ideas, and abstractions. Extroverts prefer interaction with others and tend to be action oriented. Introverts can be sociable but need tranquility to regain their energy.

• Sensing – Intuition: It indicates whether a learner prefers to perceive the world by directly observing the surrounding reality or through impressions and imagining possibilities. Sensing learners choose to rely on their five senses, are detail oriented, and trust facts. Intuitive people seek out patterns and relationships among facts, value imagination and innovation, trust their intuition, and look for the “big picture.”

• Thinking – Feeling: This indicates how the learner makes decisions, either through logic or by using fairness and human values. Thinkers prefer clear goals and objectives. Feelers focus on human values and needs as they make decisions or arrive at judgments.

• Judging – Perceptive: This indicates how the learner views the world, either as a structured and planned environment or as a spontaneous environment. Judging people are decisive, self-starters, and self-regimented. They focus on completing the task, knowing the essentials, and taking action quickly. They want guides that give quick tips. Perceptive learners are curious, adaptable, and spontaneous. They start many tasks, want to know everything about each task, and are very thorough, but often find it difficult to complete a task. Breaking down a complex project into a series of subassignments and providing deadlines will keep perceptive learners on target.

The MBTI focuses primarily on personality types for which it has proven very effective and is widely used, mostly in the context of career choices, organizations, and relationships. Having a wider scope makes it less specific to learning, and having 16 types makes it more complex to handle, although more accurate in matching individual differences. For these reasons, other simpler models have been defined and are more widely used in research on learning contexts (e.g., the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, Singer-Loomis, and Grey-Wheelright; Keirsey & Bates, 1984).

Kolb’s Learning-Styles Inventory

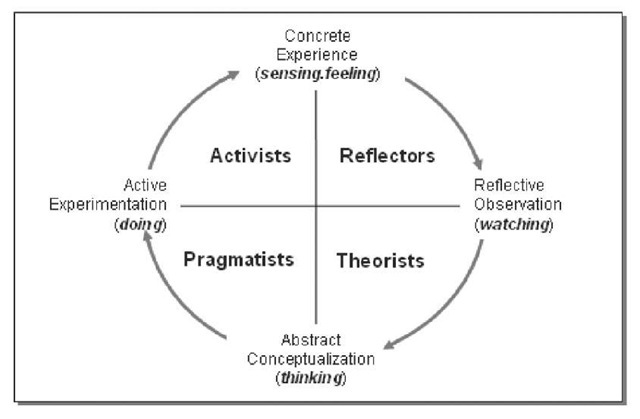

Kolb’s Learning Styles inventory (1984) can be thought of as a simpler version of the MBTI, using only two dimensions. The first dimension refers to perception (doing or watching) and the second refers to processing (thinking or feeling). The four quadrants defined by the intersection of the two dimensions (Figure 1) define personal learning styles:

• Theorists (Assimilators): They ask, “How does this relate to that?” or “What?” They have the ability to formulate theories and have strong inductive reasoning abilities, but are less interested in people and practical applications of knowledge. They respond well to interesting concepts, structured situations, and opportunities to question and probe (lectures, papers, analogies). They are often found in research, planning, and theoretical sciences.

• Pragmatists (Convergers): These ask, “How can I apply this in practice?”or “How?” They are strong in the practical application of ideas and have the ability to focus on a specific problem, but they tend to be relatively unemotional, preferring to deal with things rather than people, and have narrow technical interests. They respond well to relevance to real problems, immediate chances to try things out, and experts they can emulate (laboratories, fieldwork, observation). Quite often, they choose to specialize in the physical sciences.

• Activists (Accommodators): They may say, “Here, let me do that,” or ask, “What if?” They have the ability to involve themselves in new experiences, adapt to immediate circumstances, take risks, and solve problems intuitively, relying on others for information. They are at ease with people but are sometimes seen as impatient and pushy. They respond well to new problems and teamwork (simulations, case studies, homework). They are often found in technical or practical fields such as business, marketing, and sales. • Reflectors (Divergers): These may say, “I need time to consider that,” or ask, “Why?” They have the ability to imagine and view concrete experiences from a number of perspectives. They are interested in people and emotional elements and have broad cultural interests, but respond poorly under time pressure and unplanned situations. They respond well to thinking things through, painstaking research, and detached observation (logs, journals, brainstorming). Their vocational activities include counseling, humanities, and liberal arts.

Figure 1. Kolb’s learning styles inventory

The 4MAT framework (McCarty, Morris, McCarty, McCarty, & Kozlowski, 2001) and the learning-styles-inventory approach of Hagberg et al. (as cited in Trumbauer, Hagberg, & Donovan, 1998) are similar to Kolb’s learning styles but use different names. Gregorc (1985) modified Kolb’s dimensions by focusing on sequential and random processing of information in his mind styles: abstract sequential (theorist), concrete sequential (pragmatist), abstract random (activist), and concrete random (reflector). Sequential learners proceed one step at a time (bottom-up) while random learners look at the whole task (top-down). In this respect, it also relates to the left- and right-brain differentiation presented in the next section.

VAK: Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Perceptual Learning Styles

The VAK learning styles use the three main sensory receivers or modes to determine the dominant learning style:

• Visual learners have two subchannels: linguistic and spatial. Visual-linguistic learners like to learn from written language, they remember what has been written down even if they do not read it more than once, and they pay better attention to lectures if they watch them. Visual-spatial learners do better with charts, demonstrations, videos, and other visual materials. Visual learners appreciate graphs, mind maps, illustrations, outlines and handouts for reading and taking notes by writing or drawing in the margins, and charts showing what was presented and what will be presented next.

• Auditory learners prefer spoken messages. While reading is usually assumed to be a visual action, the information is often processed by hearing oneself say the words. While some auditory learners prefer to listen to both themselves and others, mounting evidence suggests the two types are distinct and separate: talkers and listeners. Auditory learners appreciate hearing brief explanations in the beginning and summaries in the end of every topic, the Socratic method of questioning to draw as much information as possible, verbalizing the questions, and auditory activities such as brainstorming and buzz groups.

• Kinesthetic learners do best while touching or moving. It also has two subchannels: tactile and kinesthetic. When listening to lectures, they may want to take notes. When reading, they like to scan the material before focusing on the details. They typically use color highlighters and take notes. They also appreciate activities that get them moving or doing something with their hands, working through scenarios or labs, listening to music during activities, and taking stretch breaks. Kinesthetic learners have more difficulties in traditional educational environments because most classrooms do not offer enough opportunity to move or touch.

Although learners use all three to receive and represent information, one or more of these styles is normally dominant (Baudler & Grinder, 1979; Clark, 2000).

By relating perceptual preferences to states of consciousness, Dawna Markova (1996) described the related Six Patterns of Natural Intelligence model. For example, V-K-A (seer and feeler) is someone visual in the conscious state, kinesthetic in the subconscious, and auditory in the unconscious states.

VARK: Visual, Aural, Read-Write, and Kinesthetic Perceptual Learning Styles

Niel Fleming (1995) added a fourth dimension to VAK to explicitly distinguish preferences for text from preferences for diagrammatic or iconic material. As mentioned before, this distinction appears in VAK when differentiating visual-linguistic from visual-spatial learners in the visual dimension. The VARK – Visual, Aural, Read-write, and Kinesthetic model makes these concepts more clear, giving them the same level of importance. This distinction is also in-line with the multiple-intelligences theory, presented in the next section.

Other Learning Styles

This section presents other relevant cognitive styles that appear in the literature. Additional styles can be found in Kearsley (2001), for example.

The Felder-Silverman Learning Style Model (1988) adopts five dimensions covering some psychological traits, information processing, and perceptual preferences. It classifies students as sensing versus intuitive, visual versus verbal, inductive versus deductive, active versus reflective, and sequential versus global. Most engineering and scientific instruction has been heavily biased toward intuitive, verbal, deductive, reflective, and sequential learners (Felder, 1996).

Another approach (Martinez, 1999) defines learning styles in terms of a whole-person perspective, considering how beliefs, emotions, and intentions influence learning and thinking processes in intentional, performing, conforming, and resistant learners. These attitudes relate to how successfully individuals intend to learn.

MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES

The mind is not comprised of a single representation or intellectual language, but individuals differ in the forms of these representations, their relative strengths, and the ways and ease with which these representations can be changed. In Gardner’s view, each individual’s potential can be seen in terms of his or her possession of a combination of these intelligences. The Brain Lateralization Theory is based on the idea that the two hemispheres of the brain have different functions and process information in different ways, also catering to different intelligence centers.

Left- and Right-Brain Intelligences

Individuals differ according to whether they learn more effectively through left-brain or right-brain activities, presenting a hemispheric dominance:

• Left Brain: It is analytic, linear, and logical. People with strong left-brain traits are systematic thinkers, focus on specific elements, are less likely to see the total picture, and can absorb information more easily if it is presented in a logical, linear sequence.

• Right Brain: It is global, creative, and intuitive. People with right-brain dominance generally like to take in the big global picture first, having a broad holistic view in which the whole dominates individual components. They are much more comfortable with presentations that involve visualization, imagination, music, art, and intuition.

According to Gurian (2001), hemispheric dominance and connection depends on sex. Girls’ left sides are more active and there are higher connections between hemispheres, allowing the acquirement of verbal abilities sooner and the ability to do several tasks at the same time. Boys’ right sides, however, are more active, and hemispheres are more specialized, allowing the acquirement of visio-spatial abilities sooner and better concentration in a particular task. The interplay between right and left sides provides a greater range and depth of understanding, and encourages creative expression and problem solving (McCarty et al., 2001; Vos & Dryden, 2001). Approaches that address both sides are usually called whole brain approaches (e.g., storyboards, mind maps, and self-written role play).

Pask (1975) describes a related learning style model that distinguishes serialists and holists; while Herrmann (1990) added a second dimension to the left-right brain model: cerebral-limbic, based on the task-specialized functioning ofthe physical brain, resulting in four types and closer to Kolb’s learning styles model.

Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

According to Howard Gardner’s theory (1983), there are multiple intelligences or “languages” that people speak, cutting through cultural, educational, and ability differences. Based on research results from evolutionary biology, anthropology, developmental and cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and psychometrics, he has used eight criteria to judge whether candidate ability can be counted as an intelligence and identified the existence of at least seven intelligences (Gardner; Vos & Dryden, 2001):

• Verbal-Linguistic: sensitivity to the meaning and order of words, and the ability to effectively manipulate language to express oneself rhetorically or poetically. It also allows one to use language as a means to remember information.

• Logical-Mathematical: ability to handle chains of reasoning and recognize patterns, and calculate and handle logical thinking.

• Visual-Spatial: the ability to manipulate and create mental images in order to solve problems, to perceive the world accurately, and to re-create or transform aspects of that world. This intelligence can also be exercised to a high level by individuals who are visually impaired.

• Musical-Rhythmic: the capability to recognize and compose musical pitches, tones, and rhythms. Allows people to create, communicate, and understand meanings made out of sound. Auditory functions are required for a person to develop this intelligence in relation to pitch and tone, but not necessarily for rhythm.

• Bodily-Kinesthetic: the ability to use mental abilities to coordinate body movements skillfully and handle objects adroitly. This intelligence challenges the popular belief that mental and physical activities are unrelated.

• Interpersonal: the ability to understand and communicate with people and to build relationships. It enables individuals to recognize and make distinctions about others’ feelings and intentions.

• Intrapersonal: helps individuals to distinguish among their own feelings, to build accurate mental models of themselves, and to draw on these models to make decisions about their lives.

As a result of Gardner’s later work (1999), another dimension was added:

• Naturalist: allows people to distinguish among, classify, and use features of the environment.

Spiritual intelligence was also considered by Gardner, but it didn’t meet the eight criteria mentioned earlier, and he has been gathering evidence for existential intelligence. Other authors argue that more intelligences might be considered, including common sense (Vos & Dryden, 2001).

Although they are anatomically separated from each other, Gardner claims that these several intelligences very rarely operate independently as individuals develop skills or solve problems. But still, every individual has a different set of developed intelligences, determining how easy it is to learn information presented in a particular manner—one’s learning style. However, traditional educational settings tend to emphasize logical-mathematical and verbal-linguistic intelligences.

In Equity Standards Branch (2002), the work of Gardner was used to develop a statement about capabilities, each comprising elements in more than one intelligence, and defining student profiles or capabilities as personal, linguistic, rational, creative, and kinesthetic. The work of psychologist Daniel Goleman (1995) and neuroscientist Antonio Damasio (1994) also relate to Gardner’s theory, mostly in what concerns inter- and intrapersonal intelligences.

Integrating Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences

Based on the idea that multiple intelligences deal mostly with the content of learning in distinct fields of knowledge, and that learning styles deal with the process of learning, perceiving and processing information, Silver et al. (2000) developed a holistic model to integrate and complement the two concepts in instruction, curriculum, and assessment. They use Gardner’s theory for multiple intelligences and the cognitive functions of perception and judgement, present in Jung’s psychological types and most learning styles derived from Jung’s theory. As an example, consider the verbal-linguistic intelligence as the ability to effectively manipulate language. Different learning styles would influence different manifestations of the same intelligence: sensing, the ability to use language to describe events (e.g., journalist), thinking, the ability to develop logical arguments and use rhetoric (e.g., lawyer), feeling, the ability to use language to build trust and rapport (e.g., therapist), and intuition, the ability to use metaphoric and expressive language (e.g., poet).

KNOWING AND SUPPORTING LEARNING STYLES AND MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES

From the earliest years, individuals demonstrated different ways in which they learn best, but they can develop skills in their nonpreferred areas. Such development is beneficial in creating the balance adults need to function effectively in the world. However, Jung’s model suggests that people will be at their best when they have effective command of their dominant function. To develop facility and confidence in the dominant function, children need encouragement and support for learning in their most natural, preferred ways. Adults also learn most effectively, especially when approaching new or difficult topics, when they are given opportunities to use their most effective learning style (Myers, 2000). For example, Einstein, Churchill, and Edison had learning styles that were not suited to their school styles (Vos & Dryden, 2001). The acknowledgement of different psychological types and learning styles is also important to support individuation, the process by which the individual develops into a fully differentiated, balanced, and unified personality (Jung, 1961/1989; Vos & Dryden, 2001). This section addresses the reasons and means to know learning styles, including multiple intelligences, and ways to support them.

Knowing Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences

We usually rely on our preferred learning styles to process information at an unconscious level, but we may be consciously aware of which styles we prefer (Connor & Hodgins, 2002). Knowing and understanding our learning style helps us to learn more effectively by being able to capitalize on our strengths, and also helps to improve our teaching and interpersonal skills. Knowing how to decipher the learning style of others can help in getting through to them (Lasear, 1992). Knowing the different learning styles also helps us to build learning artifacts and environments that can effectively support learning.

There are many instruments to determine learning styles, usually based on tests with several questions that will score differently in the various dimensions covered by the inherent model. The choice of a model will depend mainly on the intended use of the learning style and on preference, since different models have different scopes or slightly different approaches of the same aspects. Test results may be deceiving, if people are not sufficiently self-aware and answer based on a false self-image or based on the way they would like to be or believe they are expected to be. Even so, they are encouraged to trust their intuition and self-awareness about the results, and to repeat the test if it does not feel right. It is also important to stress that they also can learn and have abilities other than the preferred one, and that there are no right and wrong styles. They are just different.

All learning styles models can be thought of as a mandala, a Sanskrit word for magical circle, one of the oldest religious symbols found throughout the world (Clark, 2000). Jung (1961/1989) considered mandalas as symbols of wholeness that can aid people in integrating their personality. Different models can be graphically represented by distinct forms, but all of them are attempts to minimize the extreme complexity of learning. Therefore, these models do not fully explain how we learn. They tend to simplify the process by taking one perspective. It is only by looking through the different perspectives that we begin to understand the whole learning process.

Supporting Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences

Theoretically, learning styles could be used to predict what kind of pedagogical strategies would be most effective for a given individual or learning task, but research to date has not identified many robust relationships, since aptitudes and instructional treatments interact in complex patterns and are influenced by task and situation variables (Cronbach & Snow, 2001). Instead, the broad spectrum of students would be better served if disciplines could be presented in a number of ways and learning could be assessed through a variety of means.

The ideal learning environment would support all learning styles, allowing all learners the opportunity to get involved, providing for a means of reinforcement, and developing a sense of accomplishment and self-confidence. It should be flexible so that each learner could spend additional time on his or her preferred learning style. However, presenting the material in various ways and through various activities can excite the students about learning, and also allows the reinforcement of the same material, thus facilitating a faster and deeper understanding (Kolb, 1984; Lasear, 1992; Vos & Dryden, 2001).

Schroeder (1993) describes the results of an 8-year study using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, showing how university students’ learning profiles have changed in recent years and how different they are from typical university teachers’, suggesting approaches to bridge the gap. Felder (1996) describes several studies, involving either the MBTI, Kolb’s, Herrmann’s, or Felder and Silverman’s models. The different approaches and studies suggest that awareness about styles can make a difference, and that teaching should be addressed to all learning types. Frameworks like the 4MAT (McCarty et al., 2001) and the Dunns’ framework (Dunn & Dunn, 1998) have been developed to help address learning styles.

Supporting Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences with Video and Hypermedia

Hypermedia-based learning holds the potential to support various learning preferences by accommodating different media types and providing the learner with the flexibility to control the pace, sequence, and content to visit. If adequately designed, it allows learners to tailor the educational experience to meet their own unique needs, interests, and goals.

Some studies have been done to discover how hypermedia-based learning supports different learning styles. For example, Sam and Ling (2000) made a study based on Kolb’s inventory, concluding that, independent of learning style, all students had a positive attitude toward hypermedia. Most differences were found in their attitudes toward navigation, as expected: Prudent navigators (reflectors, theorists) make less navigational choices, while daring students (pragmatists, activists) explore hyperspace more freely.

In our own research, we have been addressing learning in hypervideo, or video-based hypermedia spaces (Chambel, 2003; Chambel & Guimaraes, 2002). Video holds a great potential to motivate and support learning as a powerful means of communicating meaning scenarios rapidly and efficiently. It may also support different learning styles by appealing to several modalities. However, many of the advantages recognized in hypermedia did not apply to situations where video was involved, since video used to be poorly integrated as a whole. We considered the temporal dimension to allow the addressing of video in space and time for its structuring, and for synchronization among media elements. New forms of integration, annotation, and navigation of video in hypermedia were conceived, with a special concern for the support of cognitive processes. As a result, in addition to the multiple media involved, catering to different perceptual preferences, many of the advantages related to the possibility to structure, relate, and navigate information was brought to video and its integration with other media. In the type of integrated environment we proposed, students may choose to spend more time in their preferred styles while consuming and interacting with rich multimedia materials and being exposed to other complementary perspectives.

CONCLUSION

This article presented an overview of different learning styles and multiple intelligences people exhibit and develop, determining their best suited way to learn. It presented a historical context, the main theories on learning styles and multiple intelligences, the purpose and methods of knowing and identifying learning styles, and ways of supporting them in learning environments. A special emphasis was given to the support video and hypermedia may provide.

One of the great challenges to learning support is encouraging and accommodating a full range of student diversity while promoting a uniformly high level of achievement for all students. This overview provides the basis for the understanding of the main concepts and approaches, informing the design and construction of learning environments that can effectively accommodate heterogeneous learning styles and situations, rising to the challenge.

KEY TERMS

Brain Lateralization: A theory based on the idea that the two hemispheres of the brain have different functions and process information in different ways, catering to different intelligence centers.

Hypermedia-Based Learning: Learning in hypermedia environments, allowing nonlinear access to information through links provided within text, images, animation, audio, and video. It is considered flexible, where varied instructional needs can be addressed.

Hypervideo: Refers to the integration of video in truly hypermedia spaces, where it is not regarded as a mere illustration, but can also be structured through links defined in its spatial and temporal dimensions. Sometimes called video-based hypermedia.

Individuation: The process by which the individual develops into a fully differentiated, balanced, and unified personality. A concept introduced by Carl Jung.

Intelligence: The capacity to know or understand, readiness of comprehension, or the intellect as a gift or endowment—as a classical definition. The capacity to solve problems or to create products that are valued in one or more cultural settings—as defined by Gardner.

Learning Style: A consistent way of responding to and using stimuli in the context of learning on the basis of either learned or inherited traits. Also known as cognitive preference.

Multiple Intelligences: A theory developed by Howard Gardner stating that every individual has a different set of developed intelligences or “languages” that one speaks, cutting through cultural, educational, and ability differences.

Psychological Types: Patterns of behaviour resulting from differences in mental functions preferred, used, and developed by an individual. A theory developed by Carl Jung.