introduction and background

The opportunities for students to take courses, and entire degree programs, online continue to increase, as many traditional colleges and universities have developed programs to compete with for-profit online schools that have proliferated in recent years. In 2003, The Wall Street Journal reported “an estimated 350,000 students are enrolled in fully online degree programs” (Dunham, 2003). In 2005, it was estimated that “more than 1 million students are seeking degrees entirely via the Web” (Tosto, 2005). According to Eduventures, “growth rates for online higher education greatly exceed those projected for U.S. postsecondary education overall (approximately 2%), positioning online higher education as a major growth engine” (Eduventures, 2007).

The Sloan Consortium’s purpose is “to help learning organizations continually improve the quality, scale, and breadth of their online programs ….” (Sloan, n.d.). Their 2006 survey indicated a one-year growth of about 35% in students taking online courses (Allen & Seaman, 2006), the largest percentage increase in number of online students since the first Sloan survey in 2003. In 2002, it was estimated that 1.6 million students were enrolled in an online course at a U.S. degree-granting university. That number increased to 1.9 million in 2003-2004, 2.3 million in 2005, and 3.2 million in 2006 (Allen & Seaman, 2006). In 2004, the largest growth rate in schools offering online courses occurred at private, for-profit institutions (Allen & Seaman, 2003). A separate study (Phillips, 2003) indicated that the Master ofBusiness Administration (MBA) was the most popular degree offered in a distance format in the United States and also determined that the approval ratings of employers was high as long as the provider educational institution had a recognized name to the potential employer. The MBA continues to be the most popular distance learning degree, currently offered by 130 accredited institutions, of which 48 are AACSB-accredited business schools (Phillips, 2007). According to a 2007 survey by the NationalAssociation of Colleges and Employers, the MBA degree is the top master’s degree in demand (NACE , 2007).

The Sloan Consortium reports (Allen & Seaman, 2006) define an online course as one where at least 80% of the content is delivered online and an online program as one where 80% of the courses in the program are taken online.

The term “online course” in the discussion below refers to a course in which most or all of the content, assessment, and communications are delivered via the Internet. An “online program” refers to a complete degree program in which a majority of its delivery is provided through online courses (Simon, Brooks & Wilkes, 2005).

To determine the current status of employers’ perceptions regarding online courses and programs, recent publications on the topic were reviewed, along with accreditation guidelines on the web sites of the Department of Education and the Council on Higher Education Accreditation. A confirmatory survey of perceptions of human resources (HR) personnel was also conducted.

perceptions of online courses and online degrees

The quality of education received should be a primary concern for all parties involved. Although some studies of quality have been attempted, most studies to date have focused primarily on perceptions of participants in these programs rather than on others affected by these decisions, such as employers.

Perceptions of university communities

The Sloan Consortium’s 2004 report (Allen & Seaman, 2004) indicated that a majority of academic administrators who responded believe that online learning quality is at least equal to face-to-face instruction. The Sloan report provided analyses by Carnegie Class (Doctoral/Research, Masters, Baccalaureate, Associates, and Specialized). Baccalaureate and Specialized institutions had at least half of the participants indicating that online learning outcomes were inferior to face-to-face outcomes, with Doctoral/Research and Associates institutions having the most positive results regarding online learning outcomes.

Additional analysis was done through conversion of ranks to a numeric scale so that means could be calculated by group, i.e., private for-profit, private nonprofit, and public institutions. Although the report indicated that a majority of the academic leaders who participated believe that online learning quality is at least equal to face-to-face instruction, the conversion of ranks to a numeric scale, coupled with differences in responses from those representing private nonprofit institutions and those representing public and private for-profit institutions, produced results indicating that every type of institution rated learning outcomes of online courses as at least slightly inferior to face-to-face learning, based on mean values for rankings.

Perceptions of Employers

A survey of 239 human resource (HR) professionals (Vault, 2001) found:

• About three-fourths thought the online degree would be more credible if earned at a traditional, accredited school than from an Internet-only institution.

• About one-fourth thought an online undergraduate degree would be as credible as a traditional degree, while over one-third said an online degree would be as credible for a graduate degree.

• Over half thought that job candidates should indicate whether or not their degrees were earned online.

A later survey of members of an HR organization found that about 14% thought an online degree was acceptable, with 29% saying that it was not acceptable, and 57% saying they had no preference (Aaron, n.d.).

An Online University Consortium (2004) survey of corporate decision-makers indicated that traditional universities are preferred over online programs. Results also indicated that the name of the university providing an online program is a strong consideration.

Confirmatory Study of Employer Perceptions

A confirmatory survey was conducted by the authors regarding perceptions of HR personnel about online programs. Participants were members of an HR organization in a large metropolitan area.

Demographic Data

Demographic data used for comparisons included age, gender, level of education, and number of employees. Since this study specifically targeted college-level coursework, participants were asked to indicate whether or not they have hiring responsibility for positions requiring a college degree. A large majority were responsible for hiring college graduates.

Results

A 5-point Likert-type scale was used for participants to indicate their perceptions related to online and on-campus courses and degrees, where numbers closer to 1 represented favorability toward online, and numbers closer to 5 represented favorability toward on-cam-pus.

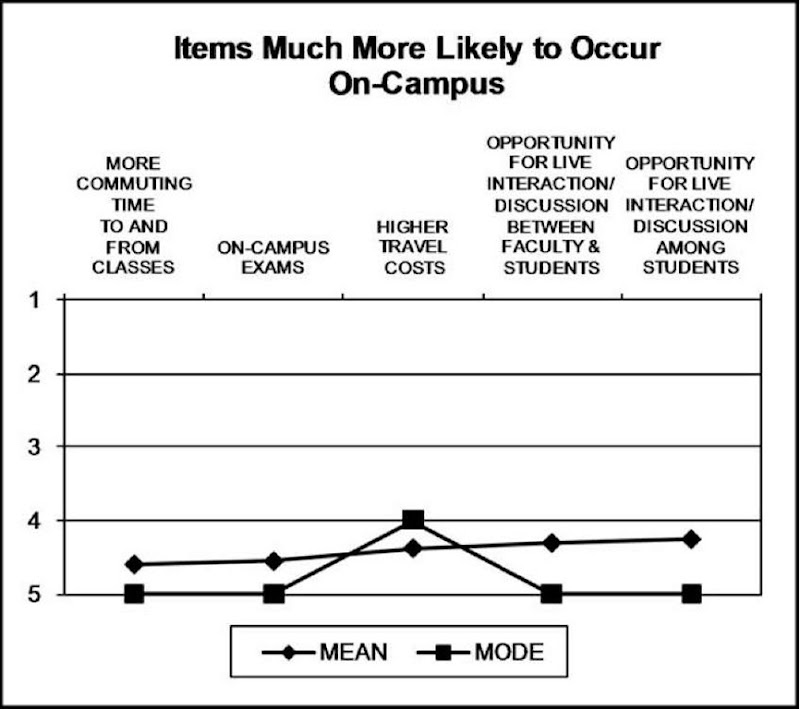

Figure 1. Items Much More Likely to Occur On-Campus

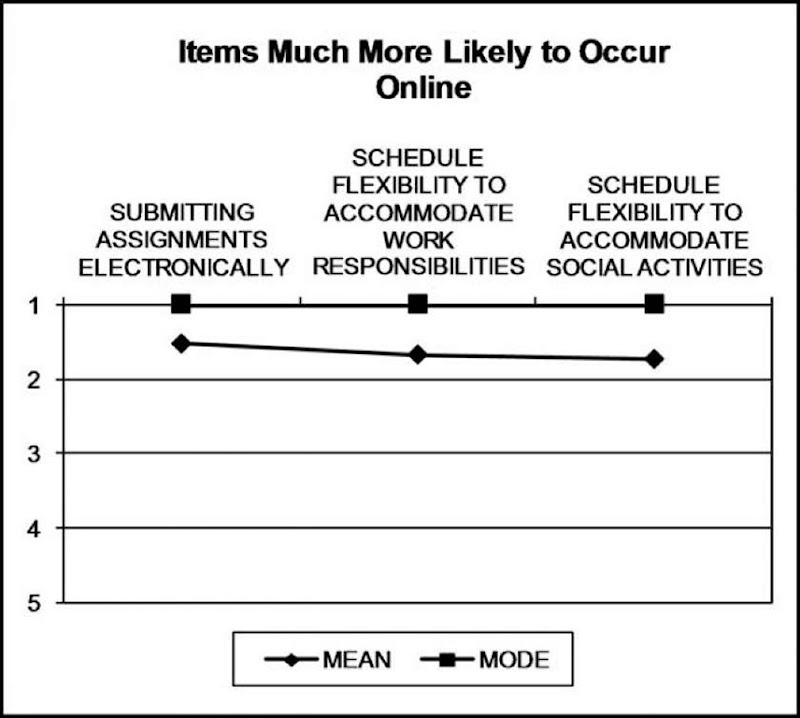

Figure 2. Items Much More Likely to Occur Online

For purposes of analyses, mean results of 4 or greater were considered to be much more likely on-campus, and results of 2 or lower were considered to be much more likely online. With a 3.0 as the midpoint, values between 2.01 and 2.99 represented some preference toward the “online” side of the scale and values between 3.01 and 3.99 on the “on-campus” side of the scale.

Five of the 27 items on the list had mean responses of 4.0 or greater, indicating that they were considered much more likely to occur on-campus. The mean and mode for the five items with mean responses of 4.0 or greater are shown in Figure 1.

Three of the 27 items had mean responses of 2.0 or lower, indicating that they were considered much more likely to occur online. All three items also had a mode of 1. The mean and mode for the three items with mean responses of 2.0 or lower are shown in Figure 2.

Slightly over half of the items (14 of 27) had a mode of 3, indicating no directional preference.

Participants were asked to indicate their overall attitudes toward individual online courses, using a scale of 1 for very favorable and 5 for very unfavorable. The overall mean response was 2.517, indicating a slight direction toward favorability of online courses. The mode was 3.

More favorable responses toward online courses came from participants older than 40, females, and participants with an educational level no higher than a Bachelor’s degree. Although the means were not strong (i.e., not below 2.0), they were below the midpoint of 3.0 and thus indicated some direction toward favorability toward online courses. The only subgroup with a mean greater than 3.0 was males. Males and those with a Master’s degree or higher had a mode of 4, tending toward unfavorability toward online courses. In all comparisons regarding online degree programs versus online courses, the mean was larger (i.e., not as favorable) for entire degree programs online than for individual courses online.

Participants were also asked to indicate their likelihood of hiring someone with an online degree. Overall, and in each subcategory, the mean was greater than 3.0, indicating more likelihood of hiring someone with an on-campus degree. The overall mean was 3.276. The mode was 3 for each category.

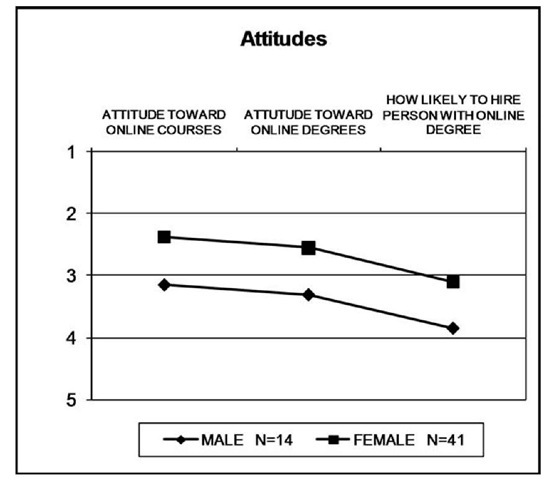

Gender. Females reported more favorable attitudes toward online courses and degrees than did males.

Figure 3. Comparisons of Means of Attitudes by Gender (1 = Very favorable; 5 = Very unfavorable).

Regarding attitude toward online courses, the mean for females was 2.39 while the mean for males was 3.15. Regarding attitude toward online degrees, the mean for females was 2.55 and was 3.31 for males. Regarding the likelihood to hire someone with an online versus on-campus degree, the mean for females was 3.10 and was 3.85 for males. A comparison of scores on attitudes toward online courses and online degrees reveals one significant and one near significant difference in means between male and female respondents. (See Figure 3.)

The difference in means for attitude toward online courses, F (1,51) = 3.94, is near-significant (p=.053) while the difference in means for attitude toward online degrees, F (1,51) = 3.39, proved insignificant. However, a comparison of mean scores on likelihood to hire a candidate with an online degree reveals a significant difference in means between males and females. The mean for this attitude, F (1,51) = 4.14, p < .05, was 3.10 for females and 3.85 for males.

Level of Education. Those respondents with Bachelor’s degrees and below (Group 1) reported having more favorable attitudes toward online courses and online degrees, while those respondents with graduate degrees (Group 2) reported having less favorable attitudes. On attitude toward online courses, Group 1 had a mean of 2.29 while Group 2 had a mean of 2.95. Regarding attitude toward online degrees, Group 1 had a mean of 2.39 while Group 2 had a mean of 3.30. As to the likelihood to hire someone with an online versus on-campus degree, the mean for Group 1 was 3.05 while the mean for Group 2 was 3.70. (See Figure 4.)

The difference in means for attitude toward online courses, F (1,56) = 3.87, is near-significant (p=.054). However, a comparison of mean scores on attitude toward online degrees and likelihood to hire a candidate with an online degree versus an on-campus degree reveals significant differences in means between males and females. The mean for attitude toward an online degree, F (1,56) = 6.89, p < .05, was 2.39 for HR professionals with Bachelor’s degrees and below and 3.30 for HR professionals with graduate degrees. Additionally, the mean for likelihood to hire a candidate with an online degree versus an on-campus degree, F (1,56) = 4.516, p < .05, was 3.05 for those with Bachelor’s degrees and below and 3.70 for those with graduate degrees.

Figure 4. Comparisons of Means of Attitudes by Educational Level (1 = Very favorable; 5 = Very unfavorable).

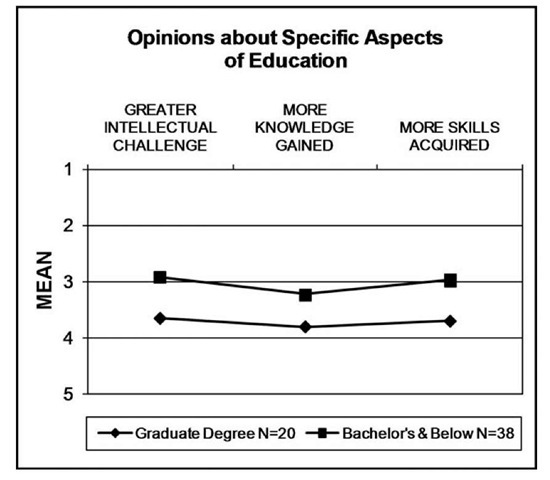

Figure 5. Comparisons of Specific Attributes by Educational Level (1 = More likely in an online course; 5 = More likely in an on-campus course).

Additionally, significant differences in means on scores for three opinions about specific aspects of education provide further evidence that HR professionals with higher levels of education hold less favorable attitudes toward online courses. Specifically, the differences in means for “greater intellectual challenge,” F (1,55) = 4.47, p < .05, “more knowledge gained,” F (1,57) = 4.061, p < .05, and “more skills acquired,” F (1,57) = 6.94,p < .05, provide further evidence that HR professionals with higher levels of education hold more favorable attitudes toward on-campus courses. (See Figure 5.)

Is accreditation a factor?

Accreditation is generally intended to be used to verify that specified standards are being met, allowing employers and prospective students to identify the quality and legitimacy of educational institutions. However, little research was found to indicate that employers’ hiring decisions include consideration of accreditation in evaluating the quality of a job applicant’s education. A The Wall Street Journal article (Dunham, 2003) indicated that most HR professionals do not spend much time considering the information about academic degrees of applicants.

The U.S. Department of Education (DOE) describes two types of accreditation: (1) institutional, and (2) programmatic or specialized. The institutional accreditation generally involves the institution as a unit and not the individual programs. The programmatic or specialized accreditation involves a review of a unit within an institution. A university might have an institutional accreditation as well as multiple programmatic or specialized accreditations.

The DOE web site (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.) provides extensive information about accreditation, including links to procedures for obtaining accreditation and a list of accrediting agencies found to be reliable authorities regarding the quality of education that its accredited institutions provide.

The Council on Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) is a nongovernmental agency that coordinates U.S. accreditation practices. Their web site (CHEA, n.d.) provides information about accreditation and other useful resources. Several regional agencies recognized by the CHEA are responsible for institutional-level accreditation. Numerous specialized or programmatic accrediting agencies are recognized by CHEA, such as the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) and the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET).

This CHEA web site identifies concerns regarding “accreditation mills,” described as “dubious providers of accreditation and quality assurance that may offer a certification of quality of institutions without a proper basis.” The term “accredited program” can be misleading because it is possible to set up an accrediting agency that is not necessarily recognized by the academic world but can put its “stamp of approval” on schools that pay a fee to join its organization. Some unrecognized agencies use names that are quite similar to the valid accreditors.

Some programs, often referred to as “diploma mills” or “degree mills,” charge significant dollar amounts for diplomas that require little or no academic work from recipients. As with some fake accreditors, these programs may have misleading names that are very similar to well-recognized educational institutions.

SUMMARY

The definition of an online course includes courses that have a high percentage (e.g., 80%) oftheir content and activities online, but the course does not have to be 100% online.

Studies have indicated that increases are occurring in the numbers of students registering for courses online and in the number of educational institutions providing online coursework.

Quality of online courses and programs is a concern, but studies to date have focused predominantly on perceptions of institutions and participants in the programs rather than on comparisons with traditional programs or on the perceptions of persons who are not currently participating in online coursework. Reports by the Sloan Consortium indicated that academic leaders of university communities offering online courses generally felt that learning quality was at least equal to face-to-face instruction, but additional data analyses of means indicated that all types of institutions had at least a slightly unfavorable rating as to learning outcomes of online courses.

Surveys of HR personnel have found that many do not state a preference regarding online versus on-cam-pus coursework. Some differences have been found in various demographic groups, such as more favorability toward online courses by older employers (age 41 or older), by females, and by those with an education that was no higher than a Bachelor’s degree. In addition, the favorability level declined with all groups when considering acceptance of entire degree programs online and declined even more regarding their willingness to actually hire someone with an online degree.

Evidence indicates that employers are more likely to accept an online degree from an educational institution whose name is familiar. Little evidence was found that employers rely on the available information about accreditation.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Employers appear to be more favorable toward online courses than for entire online degrees.

Employers need to consider the type of school and its accreditation (e.g., check with the Council on Higher Education Accreditation).

Employers should consider whether the schools have both a regional institutional accreditation and a recognized accreditation in the program for which the student is earning a degree.

Employers need to pay more attention to educational information available to them rather than assuming that schools with good-sounding names are legitimate.

FUTURE TRENDS AND RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES

The number of online course and degree offerings is likely to grow. The number of online-only providers may also increase.

Future research should explore reasons for the discrepancy between research indicating that some HR professionals would prefer that applicants indicate online degrees on their applications and other research indicating that employers do not spend much time evaluating educational backgrounds of applicants.

Additional research might look for explanations for differences that were identified in perceptions of online courses and programs by gender and by age group.

Expanded studies could look for trends; e.g., are perceptions of employers becoming more positive or more negative regarding online courses and degree programs, are employers increasing their use of resources related to quality of educational programs, etc.

key terms

Accreditation: A designation intended to indicate programs that meet specific standards; two general types of accreditation are institutional and programmatic, with coordination of programs in the U.S. by the Council on Higher Education Accreditation.

Distance Learning: Characterized by learning through audiovisual delivery of instruction that is transmitted to one or more other locations that may be live or recorded instruction but does not require physical presence of an instructor and students in the same location.

Human Resources (HR) Professionals: Employees of organizations handling various personnel issues, whose jobs may include hiring responsibilities.

On-Campus Course: Course offered wholly or in part on the campus of an educational institution, typically offered in a traditional lecture/discussion environment.

On-Campus Degree Program: A program of studies leading to a degree conferred by an educational institution wherein the majority of courses are on-campus courses.

Online Course: May be either a fully online course (content, orientation, and assessments are delivered via the Internet and students interact with faculty and possibly with one another through online technology) or a hybrid online course (some activities online and some on the traditional campus).

Online Program: A program of studies leading to a degree conferred by an educational institution wherein the majority of courses are online courses.