How do people become smart?

It’s a strange question, but it’s driven Ward Cunningham his whole life. He’s always been interested in smart people, and finding how they become that way has defined his career.

The congenial Indiana native with a laid-back Midwestern manner grew up in an era before the Internet, but remembers the next-best communications medium of that era—amateur ham radio. Fascinated by the creativity of the community that had gathered on the airwaves, Cunningham would listen into the night to conversations from all over the United States. Ham radio is a peculiar technology, where the communication waves can be repeated to larger areas, or even be "reflected" off objects such as Earth’s moon. As a result, ham radio operators can talk to others around the world.

It was the 1960s and Friday nights often had Cunningham at his radio. One evening, music was aired on a channel for about fifteen seconds, a no-no according to United States FCC rules forbidding such use of the radio spectrum. Ham operators staged a two-hour mock trial to find the perpetrator, which provided "spontaneous entertainment" for Cunningham. Like many other Internet pioneers, this early form of amateur radio "online culture" would make a lasting impact on him.

Cunningham was able to parlay that love for communication gadgets into computers when his high school in Highland, Indiana, started a special program to provide student access to mainframe computers at the Illinois Institute of Technology. A friendly math teacher at the high school let the young student use the expensive hardware through a paper-based Teletype during his free period. And thus Cunningham was introduced to the world of computing in 1966, and he was hooked.

After high school he wound up at Purdue University, and in 1968 he had access to the modern tools of the digital age. When he finished his master’s degree in computer science, he wasn’t sure what to do next. Computing had been a passion and a hobby, but now it was a matter of employment. At his graduation in 1978, the personal computer was on the cusp of changing the world. Fate would pair him up with a tech firm called Tektronix, well known in the electronics industry as the leader in making instruments for testing other computer components. The most famous was perhaps the oscilloscope, the green screens that displayed wavy sinusoidal signals bouncing around a circular display.

As a fresh graduate, Cunningham joined the computer research laboratory Tek Labs and was hired to help them research how to organize their software projects. Being an engineer himself, he had some insight into how his peers thought. He firmly believed that developers of computer software were conservative. They needed to be shown successful examples to be convinced things could be done. "The only way an engineer would work is if they saw it work in another project," Cunningham says.

But sharing knowledge within corporations was not done particularly well, and especially not in the days before the Internet. In effect, Cunningham was looking for a way to document the people, ideas, and projects within the company, so people across the organization could share in that knowledge.

In his investigation for how to accomplish this sharing, Cunningham drew inspiration from a wide variety of sources one wouldn’t immediately link to computer software, such as architect Christopher Alexander, noted museum designer Edwin Schlossberg, and cognitive linguistics professor George Lakoff.

In his book with Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff explains how humans give words meaning through metaphors, such as when we use spatial words like "high" and "low" to describe a person’s mood. To Cunningham, Lakoff’s concept resonated as a very powerful idea. In thinking about computers as the conduit for carrying messages around the Internet, he imagined metaphors spreading around and finding the right place on the Net to help. His entire quest was to find a system that supported this function, to create places to allow individuals to teach one another their metaphors.

After a decade thinking about this issue at Tektronix, Cunningham would finally discover a tool to help realize it. He happened across a brand-new software product from Apple Computer called HyperCard, which was given away for free with every Macintosh computer sold in 1987. Very quickly, people started to recognize it was something special. HyperCard was a revolutionary piece of software—it was the first easy way to make free-form hyperlinked content, allowing people to click on items on the screen to bring up other text or multimedia content. Unfortunately, Apple had no idea what a breakthrough product it had on its hands.

The idea of hypertext, or arbitrary linking among electronic documents, is usually dated back to 1945, when American scientist Vannevar Bush published "As We May Think" in the Atlantic Monthly magazine. He proposed a memex, a microfilm-based system of documents that would eventually provide inspiration for the World Wide Web. But the most prescient of his predictions was what he foresaw in hyperlinked information.

"Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified." He was basically describing what we know today as Web surfing. But given the vocabulary of the 1940s, he could only express the idea in the language of "microfilm." It’s amusing to think of today’s Internet activity happening through sheets of microfilm, but Bush was well ahead of his time on the implications of linking together information seamlessly.

As a tool to accomplish this memex function of linking and organizing data, HyperCard had a cult following, as it was easy to use, yet powerful. People could create an interlinked series of documents at the touch of a mouse. This was many years before the first Web browser was even conceived.

Fortunately, Cunningham had early access to HyperCard through a former Tektronix employee named Kent Beck, with whom he had worked. Beck had left to work for Apple Computer and happened to be in Oregon on a visit, and gave his old friend Ward something to see. "Kent Beck showed me HyperCard, which he first got his hands on after joining Apple. It was called WildCard then. I was blown away."14

In HyperCard, Cunningham saw a tool that could help him with his knowledge-sharing project. "I wanted something kind of irregular, something that didn’t fit in rows and columns." HyperCard used the idea of a "stack" of virtual index cards, in which the user could easily create new cards, create links between them, and place content on them. Putting a picture, sound, or video onto a card was as easy as inserting it and dragging it around on the screen. You could also put virtual buttons on cards that could respond to clicks and other commands.

The brainchild of Apple programmer Bill Atkinson, HyperCard was originally given away for free in 1987 and became incredibly popular with seasoned computer programmers, novice users, and educational institutions. It was easy to understand, easy to program, and incredibly powerful for creating content. No programming experience was necessary, and even kids were getting into the action, creating their own "stacks" of fun content.

Ward got his hands on HyperCard and started a simple database of cards to store written text and diagrams. He started to see the "stack" grow with information about personnel, their experiences, and descriptions of their projects. It became a multimedia scrapbook of company practices.

But there was something Ward didn’t like about HyperCard. It was too cumbersome to create new cards and link to them. In the middle of his thinking process, the technical clicks and keystrokes of getting ideas organized in HyperCard got in the way.

To make links between cards, you would bring up the first card, then go to the destination card and tell HyperCard to make a button leading there, then go back to the original card and drop the new button in place.

"In those three simple steps you would have a hyperlink," recalled Cunningham. "But the part I didn’t like is you had to go to the card you wanted to end up, because I wanted to write about all these ideas and people and projects, that kind of had no boundary. There was always another idea, always another person. It was a big company. So there was not going to be any completeness. There was going to be this frontier where I was referring to people I hadn’t described yet or to projects that I didn’t know what they were."15

Even though the mechanics of creating new cards and links was simple and straightforward, it was still cumbersome. Even a slight interruption during the creative process meant ideas were lost, as the different steps were disrupting the free flow of thinking and writing.

Cunningham wanted a solution that was transparent and quick—something that wouldn’t disrupt his stream of thought.

Because HyperCard was also programmable, he could write new computer code that could extend the functionality of the "stack" of cards beyond what Apple provided. Cunningham decided he could do something better. He created a box on each card into which the user could type a list of titles. Creating a link to a page was as simple as typing the new word or phrase into the list, such as "Project X" or "Joe Smith." Clicking on "Joe Smith" would bring up the card of that same name. You didn’t have to manually create a link or even know if that card existed. You simply named the card you wanted, and it would transport you there.

But what if the card did not exist yet? Cunningham programmed the software so a beeping sound indicated a missing card. His innovation? A card could be created automatically simply by pressing and holding down the mouse button. This lingering "click-and-hold" action was programmed to tell HyperCard to create a new card automatically.

"And the effect was, it was just fun to do. You say ‘I know something about that,’ and you just jam your finger into that screen, with the aid of the mouse, and you made things. . . . Boom there it is, and you start typing." He was like a magician, creating cards on the fly with the long press of the mouse.

Browsing Collaborators

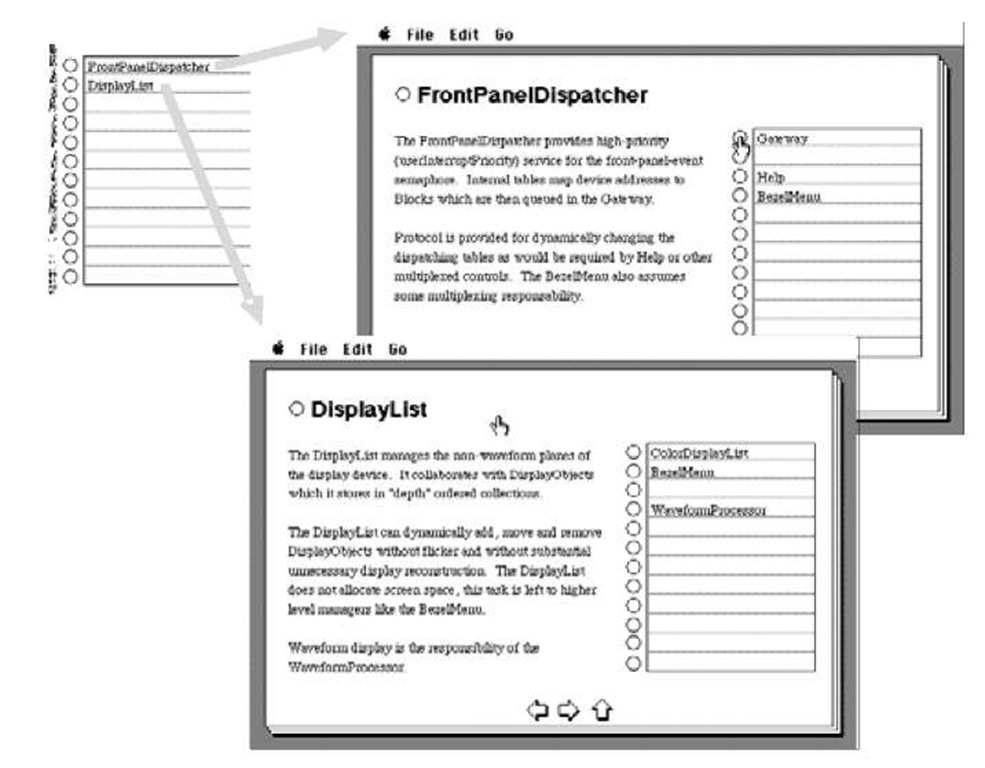

Click to browse a collaborator, press and hold to create and link a new collaborator card.

In creating this simple mechanism, Cunningham enabled individuals to get their thoughts and ideas into the stack in the quickest way possible. Around the hallways of Tektronix, people started to hear about Ward’s fun hyperlinked experiment. He got more and more visitors.

"I heard you had that cool HyperCard thing," a colleague would say, appearing at Cunningham’s office doorway.

Coworkers would sit in front of his boxy Macintosh II computer and wade through his stack of cards, adding and correcting things on this new fast tool, with nothing more than minutes of training. It was natural, fast, and addictive. "I couldn’t get them out of my office.

"We’d get to poking through people and projects and so on when my guests would invariably say, ‘that’s not exactly right.’ So we’d fix it right then and there. And we’d add a few missing links and go fix them too. The stack was captivating. We were often late for lunch."16

As Cunningham worked more with HyperCard, it became clear that he had come up with a fast and easy way of organizing this interlinked information. He described his creation as "densely linked," as having multiple paths to arrive at the same data, which made it a powerful tool. The problem was, it remained an island—the "stack" of linked information was stranded on that one computer. This was still the early days of the personal computer; networking was not something widely available.

Sitting in front of the computer and editing the stack was a potent demonstration of the capabilities of hypertext. But you still had to get that person seated in front of the computer. Growing Cunningham’s stack of information still meant workmates had to visit his office. Physical movement of information by carrying a floppy disk, comically called "Sneakernet," as opposed to a real networked computing, didn’t allow for real-time live collaboration.

Even though Ward knew he was onto something with his creation, it was a temporary dead end. The solution to Sneakernet would require some waiting. It would be another few years before connecting office computers with a network would become commonplace, and the Internet would not become widespread for another few years.

It also did not help that the Macintosh, and by extension HyperCard, was an unconventional choice for the workplace in the 1980s. Apple Computer was locked in a bitter struggle for the desktop computer market with the likes of Intel and Microsoft. While HyperCard was incredibly powerful and critically acclaimed, it was still considered a toy. There were good reasons for this label. HyperCard was designed around the original Macintosh black-and-white nine-inch screen, and was stuck with that small size for many years despite computer displays getting bigger and bigger.

HyperCard was also an odd product for Apple to manage. Because it was given away, something Apple’s esteemed creator Bill Atkinson demanded, the company made no direct revenue from it. So while it became quite popular, it was hard for Apple, primarily a computer hardware company, to justify serious resources to develop it further.

The irony is that HyperCard was revolutionary and popular, with entire businesses based on its powerful capabilities, but Apple let it wither on the vine. In the 1980s, Apple was struggling to be relevant in a world with more conventional office productivity software from Microsoft, Novell, and Lotus. HyperCard didn’t really fit into the picture.

But despite being ahead of its time, HyperCard and its legacy would have a profound impact on the development of the Web and wikis.