Atlahua

Aztec sea-god with apparent Atlantean provenance.

Atlaintika

In Euskara, the sunken island, sometimes referred to as “the Green Isle,” from which Basque ancestors arrived in the Bay of Biscay. Atlaintika’s resemblance to Plato’s Atlantis is unmistakable.

Atlakvith

A 13th-century Scandinavian saga preserving and perpetuating oral traditions going back 1,500 years before, to the late Bronze Age. Atlakvith (literally, “The Punishment of Atla[ntis]“) poetically describes the Atlantean cataclysm in terms of Norse myth, with special emphasis on the celestial role played by “warring comets” in the catastrophe.

Atlamal

Like Atlakvith, this most appropriately titled Norse saga tells of the “Twilight of the Gods,” or Ragnarok, the final destruction of the world order through celestial conflagrations, war, and flood. Atlamal means, literally, “The Story of Atla[ntis].”

Atlan

Today’s Alca, on the Gulf of Uraba, it was known as Atlan before the Spanish Conquest. Another Venezuelan “Atlan” is a village in the virgin forests between Orinoco and Apure. Its nearly extinct residents, the Paria Indians, preserve traditions of a catastrophe that overwhelmed their home country, a prosperous island in the Atlantic Ocean inhabited by a race of wealthy seafarers. Survivors arrived on the shores of Venezuela, where they lived apart from the indigenous natives. In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, “Atlan” meant, literally, “In the Midst of the Sea.” Atlan’s philological derivation from Atlantis, kindred meaning, and common account of the lost island comprise valid evidence for Atlanteans in Middle and South America, just where investigators would expect to find important cultural clues.

Atland

The Northern European memory of Atlantis, as preserved in the medieval account of a Frisian manuscript, the Oera Linda Bok, or “The Topic of How Things Were in the Old Days.”

Atlanersa

King of Nubia in the fifth century b.c. The name means “Prince or Royal Descendant (ersa) of Atlan,” presumably the Atlantis coincidentally described by Plato in Athens at the same time this monarch ruled Egypt’s southern neighbor. Unfortunately, nothing else is known about Atlanersa beyond his provocative name, nor have any Atlantean traditions been associated with the little that is known about Nubian beliefs.

Atlantean

As a pronoun, an inhabitant of the island of Atlas or its capital, Atlantis. As an adjective, it defines anything belonging to the culture and society of the civilization of Atlantis. In art and architecture, Atlantean describes an anthropomorphic figure, usually a male statue, supporting a lintel often representing the sky. Until the early 20th century, “Atlantean” was used to characterize the outstanding monumentality of a particular structure, an echo of the splendid public building projects associated with Atlantis.

Atlantean War

The Egyptian priest quoted in Plato’s Dialogue, Timaeus, reported that the Atlanteans, at the zenith of their imperial power, inaugurated far-reaching military campaigns throughout the Mediterranean World. They invaded western Italy and North Africa to threaten Egypt, but were turned back by the Greeks, who stood alone after the defeat of their allies. Successful counteroffensives liberated all occupied territories up to the Strait of Gibraltar, when a major seismic event simultaneously destroyed the island of Atlantis and the pursuing Greek armies. The reasons or causes for the war are not described.

The Egyptian priest implies that the Greeks perished in an earthquake on the shores of North Africa (northern Morocco) fronting the enemy’s island capital. He spoke of “the city which now is Athens” (author’s italics), meaning that the Greeks he described belonged to another city that preceded Athens at the same location during pre-classical times. This represents an internal dating of the war to the late Bronze Age (15th to 12th centuries b.c.) and the heyday of Mycenaean Greece.

There is abundant archaeological evidence for the Atlanteans’ far-ranging aggression described by the Egyptian priest. Beginning in the mid-13th century b.c., the Balearic Isles, Sardinia, Corsica, and western Italy were suddenly overrun by helmeted warriors proficient in the use of superior bronze weapons technology. At the same time, Libya was hit by legions of the same invaders described by the Greek historian Herodotus (circa 500 b.c.) as the “Garamantes.” Meanwhile, Pharaoh Merenptah was defending the Nile Delta against the Hanebu, or “Sea Peoples.” His campaigns coincided with the Trojan War, in which the Achaeans (Mycenaean Greeks) defeated the Anatolian kingdom of Ilios and all its allies. Among them were 10,000 troops from Atlantis, led by General Memnon. These widespread military events from the western Mediterranean to Egypt and Asia Minor comprised the Atlantean War described in Timaeus.

It is possible, however, that Atlantean aggression was not entirely military but more commercial in origin. Troy, while not a colony of Atlantis, was a blood-related kingdom, and the Trojans dominated the economically strategic Dardanelles, gateway to the Bosphorous and rich trading centers of the Black Sea. It was their monopoly of this vital position that won them fabulous wealth. In fact, it appears that the Atlanteans founded an important harbor city in western coastal Anatolia just prior to the Trojan War (see Attaleia). But the change of fortunes in Asia Minor also won them the animosity of the Greeks, who were effectively cut off from the Dardanelles. This was the tense economic situation that many scholars believe actually led to the Achaean invasion of Troy.

The abduction of Helen by Paris, if such an event were not merely a poetic metaphor for the “piracy” of which the Trojans were accused, was the dramatic incident that escalated international tensions into war—the last straw, as it were, after years of growing animosity. Thus, the victorious Greeks portrayed the defeated Atlanteans as having embarked upon an unprovoked military conquest, when, in reality, both opposing sides were engaged in economic rivalry, through Troy, for control of the Bosphorous and its rich markets. These commercial causes appear more credible than the otherwise unexplained military adventure supposedly launched by the Atlanteans in a selfish conquest of the Mediterranean World, as depicted in Timaeus. On the other hand, our pro-Atlantean example of historical revision is at least partially undermined by the Atlanteans’ unquestionable aggression against Egypt immediately after their defeat at Troy and again, 42 years later.

Atlanteotl

An Aztec (Zapotec) water-god who “was condemned to stand forever on the edge of the world, bearing upon his shoulders the vault of the heavens” (Miller and Rivera, 4). This deity is practically a mirror image in both name and function of Atlas-Atlantis, powerful evidence supporting a profound Atlantean influence in Mesoamerica.

Atlantes

Described by many classical writers (Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, etc.), a people who resided on the northwestern shores of present-day Morocco. They preserved a tradition of their ancestral origins in Atlantis, and appear to have been absorbed by the eighth-century invasion of their land by the forces of Islam. Notwithstanding their disappearance, their Atlantean legacy has been preserved by the Tuaregs and Berbers, who pride themselves on their partial descent from the Atlantes.

Atlanthropis mauritanicus

A genus name assigned by the French anthropologist, Camille Arambourg, to Homo erectus finds at Ternifine, Algeria. It represented a slight development, considered “superfluous” by some scholars, of a type along the Atlantic shores of North Africa and may indicate that early man followed migrating animal herds across former land bridges onto the island of Atlantis. There the abundance of game and temperate climate fostered further evolutionary steps toward becoming Cro-Magnon. The Atlanthropis mauritanicus hypothesis is bolstered by Cro-Magnon finds made in some of the Canaries, the nearest islands to the suspected location of Atlantis. Atlanthropis mauritanicus is also referred to as Homo erectus mauritanicus.

Atlantiades

Atlantises, Daughters of Atlas.

Atlantic Ocean

The sea that took its name from the land that once dominated it, Atlantis, just as the Indian Ocean derived its name from India, the Irish Sea from Ireland, the South China Sea from China, and so on.

Atlant ca

A four-volume magnum opus by Swedish polymath Olaus Rudbeck. Published in the year of his death, 1702, Atlantica was eagerly sought out by Sir Isaac Newton and other leading 18th-century scientists. It describes “Fennoscandia,” roughly equivalent to modern Sweden, as the post-deluge home of Atlantean survivors in the mid-third millennium b.c.

La Atlantida

Literally “Atlantis”; an opera (sometimes performed in concert form) by Spain’s foremost composer, Manuel de Falla (1876 to 1946). When a youth, de Falla heard local folktales of Atlantis, and learned that some Andalusian nobility traced their line of descent to Atlantean forebears. De Falla’s birthplace was Cadiz, site of the Spanish realm of Gadeiros, the twin brother of Atlas and king mentioned in Plato’s account (Kritias) of Atlantis.

La Atlantida describes the destruction of Atlantis from which Alcides (Hercules) arrives in Iberia to found a new lineage through subsequent generations of Spanish aristocracy. One of the opera’s most effective moments occurs immediately after the sinking of Atlantis, when de Falla’s music eerily portrays a dark sea floating with debris moving back and forth upon the waves, as a ghostly chorus intones, “El Mort! El Mort! El Mort!” (“Death! Death! Death!”).

Atlantida is also the title of a Basque epic poem describing ancestral origins at “the Green Isle” which sank into the sea.

Atlantika

In their thorough examination of the so-called “Aztec Calendar Stone,” Jimenez and Graeber state that Atlantika means “we live by the sea,” in Nahuatl, the Aztec language (67).

Atlantikos

Ancient Greek for “Atlantis,” the title of Solon’s unfinished epic, begun circa 470 b.c.

Atlantioi

“Of Atlantis.” The name appears in the writings of various classical writers (Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, etc.) to describe the contemporary inhabitants of Atlantic coastal northwestern Africa.

Atlantis

Literally “Daughter of Atlas,” the chief city of the island of Atlas, and capital of the Atlantean Empire. From the welter of accumulating evidence, a reasonable picture of the lost civilization is beginning to emerge: As Pangea, the original supercontinent, was breaking apart about 200 million years ago, a continental mass trailing dry-land territories to what is now Portugal and Morocco was left mid-ocean, between the American and Eur-African continents pulled in opposite directions. This action was caused by seafloor spreading, a process that moves the continents apart by the operation of convection currents in the mantle of our planet. The resultant tear in the ocean bottom is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a seismic zone of volcanic and magmatic activity extending like a narrow scar from the Arctic Circle to the Antarctic. The geologic violence of the Ridge combined with rising sea levels to eventually reduce the Atlantic island’s dry-land area.

About 1.5 million years ago, early man (Homo erectus mauritanicus, or Atlanthropis mauritanicus) pursued animal herds across slim land bridges leading from the western shores of North Africa onto the Atlantic island. These earliest inhabitants found a natural environment of abundant game, extraordinarily fertile volcanic soil with numerous freshwater springs, rich fishing, and a year-round temperate climate. Such uniquely superior conditions combined to stimulate human evolutionary growth toward the appearance of modern or Cro-Magnon man. With increases in population fostered by the nurturing Atlantean environment, social cooperation gradually developed to produce the earliest communities— small alliances of families for mutual assistance. These communities continued to expand, and in their growth, they became complex. The greater the number of individuals involved, the greater the number and variety of needs became, as well as technological innovations created by those needs, until a populous society of arts, letters, sciences, and religious and political hierarchies eventually emerged. The island of Atlas was, therefore, the birthplace of modern man and home of his first civilization.

Time frames are very controversial among Atlantologists, and this issue is addressed in the text that follows. Conservative investigators tend to regard Atlantean civilization as having come into its own sometime after 4000 b.c. By the end of that millennium, the Atlanteans were mining copper in the Upper Peninsula of North America; establishing a sacred calendar in Middle America; building megalithic structures such as New Grange in Ireland, Stonehenge in Britain, and Hal Tarxian at Malta; as well as founding the first dynasties in Egypt and Mesopotamia’s earliest city-states.

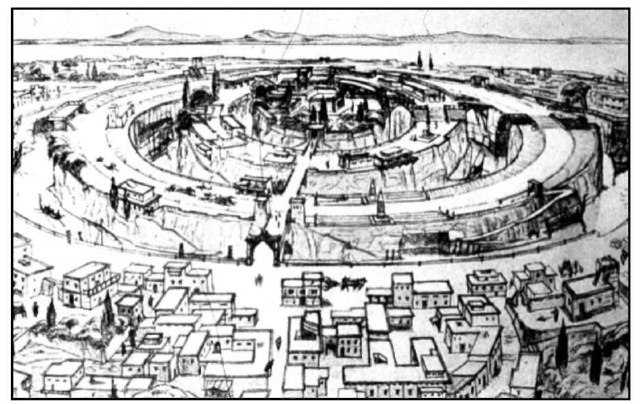

The island of Atlas was named after its chief mountain, a dormant volcano. The chief city and imperial capital was Atlantis, arranged in alternating rings of land and water interconnected by canals. High walls decorated with gleaming sheets of polished copper alloys and precious stones, featuring regularly spaced watchtowers, encircled the outer perimeter, which was separated from Mt. Atlas on the north by a broad, fair plain. The inner rings were occupied by a spacious racetrack, for popular events of all kinds; military headquarters and training fields; a bureaucracy; the aristocracy; and the royal family, who resided in a palace near the Temple of Poseidon, at the very center of the city. This temple was the most sacred site in Atlantis—the place where holy tradition claimed that the sea-god Poseidon mated with a mortal woman, Kleito, one of the native inhabitants, to produce five sets of male twins. These sons became the first Atlantean kings, from whom the various colonies of the Empire derived their names. The first of these was Atlas, earliest ruler of the island in the new order established by Poseidon.

By the 13th century b.c., the Atlantean Empire stretched from the Americas to the western shores of North Africa, the British Isles, Iberia, and Italy, with royal family and commercial ties as far as the Aegean coasts of Asia Minor. The Atlanteans were responsible for and dominated the Bronze Age, during which they rose to the zenith of their material and imperial success to become the leading power of late pre-classical times. However, their expanding trade network eventually clashed with powerful Greek interests in the Aegean, resulting in a long war that began at Troy and spread to Syria, the Nile Delta, and Libya, climaxing at the western shores of North Africa.

Initially successful, the Atlantean invaders suffered defeats at the hands of the Greeks, who had just pushed them out of the Mediterranean World when a natural catastrophe destroyed the island of Atlantis, along with most of its population, after a day and night of geologic upheaval. The same event simultaneously set off a major earthquake in present-day Morocco, where the pursuing Greek armies had gathered, and engulfed them, as well. Atlantean survivors of the destruction arrived as culture-bearers in different parts of the world, founding new civilizations in the Americas, and left related flood legends as part of the folk traditions of peoples around the globe.

Illustration of Atlantis based on the description in Plato’s Kritias. From Unser Ahnen und die Atlanten, Nordliche Seeherrschaft von Skandinavien bis nach Nordafrika, by Albert Herrmann.

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

The first modern, scientific examination of Atlantis begun in 1880 by Ignatius Donnelly and published two years later by Harper Brothers (New York). Certainly the most influential topic on the subject, it triggered a popular and controversial revival of interest in Atlantis that continues to the present day.

Donnelly’s use of comparative mythologies to argue on behalf of Atlantis-as-fact is encyclopedic, persuasive, and still represents a veritable gold mine of information for researchers. His geology and oceanography were far ahead of his time, while his conclusions were largely borne out by advances made during the second half of the 20th century in the general acceptance of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics. Atlantis: The Antediluvian World has been unfairly condemned for its relatively few failings, mostly by Establishment dogmatists and cultural isolationists to whom any serious suggestion of Atlantis is the worst heresy. But no scholarly position has been able to remain unscathed after 100 years of scientific progress, and, for the most part, Donnelly’s work has stood the test of time. In the first 10 years after its publication, the topic went through 24 editions, making it an extraordinary best-seller, even by modern standards. It has since been translated into dozens of languages, has sold millions of copies around the world, and is still in print—all of which qualifies the topic as a classic, just as vigorously condemned and championed today as it was more than a century ago.

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World poses 13 fundamental positions, which formed the basis of Atlantology. These predicate that:

1) Atlantis was a large island that lay just outside the Strait of Gibraltar in the Atlantic Ocean.

2) Plato’s account of Atlantis is factual.

3) Atlantis was the site where mankind arose from barbarism to civilization. Donnelly was the first to state this view, which, although not mentioned in Plato’s Dialogues, is suggested by the weight of supportive evidence found in the traditions of peoples residing within the former Atlantean sphere of influence.

4) The power of Atlantis stretched from Pacific coastal Peru and Yucatan in the west to Africa, Europe, and Asia Minor in the east.

5) Atlantis represented “a universal memory of a great land, where early mankind dwelt for ages in peace and happiness”—the original Garden of Eden.

6) The Greek, Phoenician, Hindu, and Scandinavian deities represented a confused recollection in myth of the kings, queens, and heroes of Atlantis.

Although important Atlantean themes interpenetrate both Western and Eastern mythologies, as he successfully demonstrated, Donnelly overstated that relationship by reducing all the ancient divinities to merely mythic shadows of mundane mortals.

7) The solar cults of ancient Egypt and Peru derived from the original religion of Atlantis.

8) Egypt, whose civilization was a reproduction of Atlantis, was also the oldest Atlantean colony.

Early Dynastic Egypt was a synthesis of indigenous Nilotic cultures and Atlantean culture-bearers who arrived at the Nile Delta during the close of the fourth millennium b.c. The hybrid civilization that emerged was never a “colony” of Atlantis, although Donnelly was right in detecting numerous aspects of Atlantean culture among the Egyptians.

9) The Atlanteans, responsible for the European Bronze Age, were the first manufacturers of iron, as well.

While persuasive evidence for this last argument is scant, Donnelly’s identification of the Atlanteans with the bronze-barons of the Ancient World is among his most valid and important positions.

10) The Phoenician and Mayan written languages derived from Atlantis. Phoenician letters evolved from trade contacts with the Egyptians, whose demotic script was simplified by merchants in Lebanon. If Egyptian and Mayan hieroglyphs are both Atlantean, they should be at least partially intertranslatable, which they are not. Even so, they may have evolved into separate systems over the millennia from a shared parent source in Atlantis, because at least a few genuine comparisons, known as cognates, between the two have been made.

11) Atlantis was the original homeland of both the Aryan and the Semitic peoples. What later became known as the so-called “Indo-Europeans” may have first arisen on the Atlantic island, and the Atlanteans were unquestionably Caucasoid. But such origins are deeply prehistoric, and any real proof is very difficult to ascertain. More likely, the Atlanteans were direct descendants of Cro-Magnon types, whose genetic legacy has been traced to the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands, the native Guanches, direct descendants of Atlantis. Donnelly mistakenly accepted the Genesis story of the Great Flood and related references in Old Testament and Talmudic literature as evidence for Aryan (Japhethic), as well as Semitic origins in Atlantis. In truth, the Hebrews incorporated some ancient Gentile traditions, such as the Deluge, into their own mosaic culture. Even so, the Phoenicians were in part descended from the invading “Sea Peoples” of lost Atlantis in the early 12th century b.c.

It was the depredations of these Atlantean survivors-turned-privateers that ravaged the shores of Canaan, thereby making possible a takeover of the Promised Land by the Hebrews. They intermarried with the piratical Gentiles to produce the mercantile Phoenicians. Their concentric capital at Carthage and prodigious seafaring achievements were evidence of an Atlantean inheritance. These influences, however, are after the fact (the destruction of Atlantis). Even so, Edgar Cayce spoke of a “principle island at the time of the final destruction” he called “Aryan.” Later, he described “the Aryan land” as Yucatan, where a yet-to-be discovered Hall of Records contains original documents pertaining to Atlantis.

12) Atlantis perished in a natural catastrophe that sank the entire island and killed most of its inhabitants.

13) The relatively few survivors arrived in various parts of the world, where their reports of the cataclysm grew to become the flood traditions of many nations.

The late 19th-century publication of Atlantis: The Antediluvian World marked the beginning of renewed interest in Atlantis, and is still among the best of its kind on the subject.