Generalization about West Africa is made difficult by the size (roughly 3,000 miles west to east, and half that north to south) and diversity of the region, as well as by the problematic character of the terms available to describe it, and the significance that regional scholarship has played in national traditions of anthropology outside Africa.

Region: definition and contemporary states

By convention, West Africa is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the south and west and by the world’s largest desert, the Sahara, to the north. However these boundaries are most significant for the influences that flowed across them. Via its Atlantic seaboard, West Africa was incorporated into a system of world trade emergent from the late fifteenth century — especially through the slave trade. Subsequent European colonization and Christian missionization proceeded largely, but not exclusively, from the coast. Trans-Saharan relations, especially trade relations with the Maghreb, have remained crucial in economic, political and religious terms, and established the links by which Islam became the predominant religion in the north of the region. An eastern boundary between West and Central Africa or the Sudan can be defined only arbitrarily.

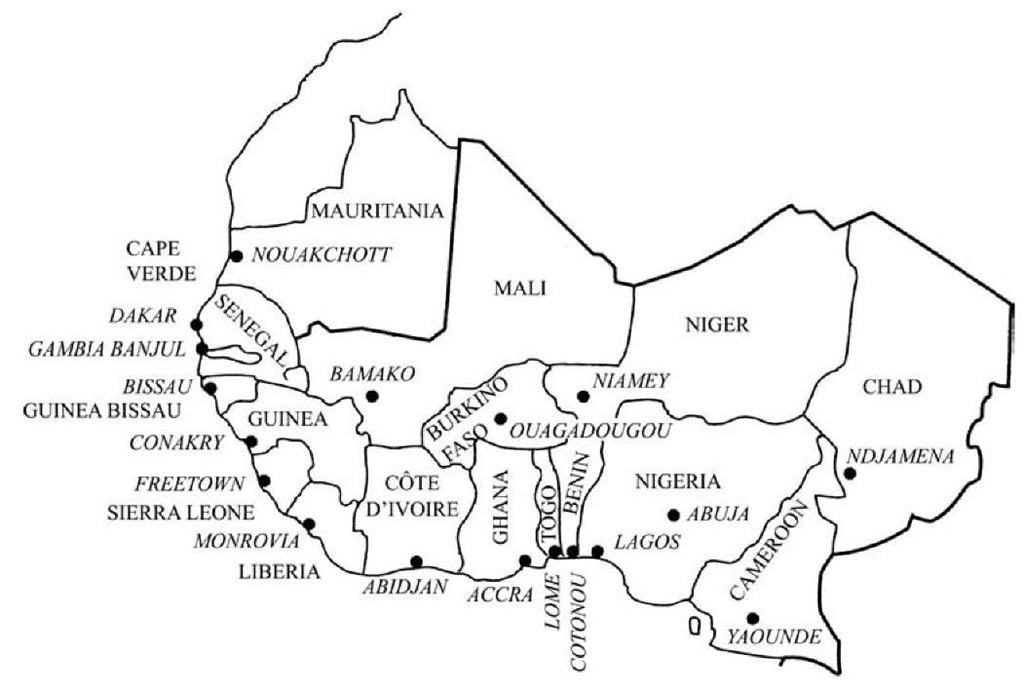

Including Chad and Cameroon, West Africa consists of eighteen formally independent states (see Map 1), some of them amongst the poorest in the world. These states were defined in the course of European colonization, which took place largely between 1885 and 1906, and they became independent between 1957 (Ghana) and 1974 (Guinea-Bissau). Despite the brevity of the colonial period, and the very uneven effects of colonial rule on different aspects of West African life, among colonialism’s legacies to West Africans were a framework of states varying in size with haphazard relations to existing differences of language and ethnicity, and three official languages of European origin. The Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ghana and Nigeria were British colonies and are now officially anglophone countries. Liberia, a fifth anglophone country, was declared a republic in 1847 following the establishment of settlements by freed American slaves. The anglophone states, which predominate in terms of West African population (Nigeria alone accounting for more than half), are surrounded by territorially more extensive francophone states, most of which formed part of Afrique Occidentale Franfaise: Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad are extensive, landlocked states; Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, Cote d’lvoire and Benin have access to the Atlantic Ocean. Togo and Cameroon, initially German colonies of greater extent than today, were mandated to Britain and France after the First World War. As a result, Cameroon is officially bilingual in English and French. Guinea Bissau and the Cape Verde Islands are small Portuguese speaking countries. The coastal states of West Africa are typically marked by pronounced north—south divisions such that southerners are more likely to be Christian and, especially on the coast, may belong to ‘creole’ cultures. Northerners, in common with citizens of land-locked states, are more likely to be Muslim and relatively less affected by European influences.

Map West Africa: contemporary states.

Language

West Africa may also be envisaged as a tapestry of language and ethnicity which predates colo-nialization. Three distinct language families are represented, each found also outside West Africa: in the North, Nilo-Saharan includes both Kanuri and Songhai, while Hausa, spoken by more West Africans than any other indigenous language, belongs to Afro-Asiatic (which also includes Arabic). Languages spoken in the south and west belong to the extensive Niger-Congo family which also includes the Bantu languages that predominate in central, eastern and southern sub-Saharan Africa. Among the important members of this group are Wolof and Mande in the west, More (Mossi) in the centre, and Akan-Twi, Fon-Ewe, Yoruba, and Igbo in the south; Fulfulde is the most widely distributed language in this group by virtue of the historically pastoral mode of life of its speakers, the Fulani (Peul, French). Distinguishable West African languages are extremely numerous — Nigeria alone has in excess of four hundred. Most West Africans are multilingual in African languages, and may additionally speak a language of European origin, Arabic (in the north), or pidgin English (in the south).

Geography

West Africa is characterized by strongly seasonal rainfall which divides the region into ecological bands running from west to east: southwards from the Sahel bordering the Sahara, savanna grasslands give way to woodlands, then to rain forests and the coastal regions with local mangrove swamps. Quick ripening grains (millet and guinea corn) are favoured in the north where the rains fall for between three and seven months. In the wetter southern regions, rice predominates in the west where rainfall has a single annual peak, while yam is a staple of the forested east which has a twin-peak rainfall regime. Introduced crops, like maize and cassava, are grown widely. Contrary to some earlier stereotypes, West African farmers respond innovatively to the management of complex local environments, using intercropping to achieve reliable yields in the light of labour availability, climatic uncertainties and their requirements for subsistence and cash (Richards 1985). Division of labour varies widely from predominantly male farming, in much of Hau-saland, to predominantly female farming, in the Bamenda Grassfields of Cameroon. Most regions fall between these extremes, with male farmers carrying out much of the intensive labour of short duration and female farmers taking responsibility for recurrent labour (Oppong 1983).

Ethnic groups

Ethnic divisions are at least as numerous as languages, to which they are related but not identical. Although ‘tribal’ names have been used to identify the subjects of ethnographic monographs, the status of these terms is controversial. Contemporary ethnic identities have developed from differences between people that predate colonialization; however, the pertinence of these distinctions, the ethnic names used to label them, and precise criteria of inclusion and exclusion from current ethnic categories have changed demonstrably over the last hundred years. The colonial use of ‘tribal’ labels for administrative convenience, as well as postcolonial competition between groups defining themselves ethnically for control of resources of the state, mean that the ethnic map of West Africa must be understood as a contemporary phenomenon with historical antecedents, rather than as ‘traditional’.

A majority of West African peoples can be classified roughly into peoples of the savannah and peoples of the forest margins and forests. Substantial minorities which do not fit into this binary division include: the peoples of the ‘middle belt’, especially in Nigeria; the coastal peoples and creolized descendants of African returnees; and the Fulani pastoralists. Developing an argument stated in strong terms by J. Goody (1971): relative to Europe, West Africa can be characterized as abundant in land and low in population. Precolonially, West African forms of social organization rested on direct control over rights in people defined in terms of kinship, descent, marriage, co-residence, age, gender, occupancy of offices, pawnship and slavery. Political relations were defined by the extent of such relations rather than by strict territoriality. Relations between polities in the savanna depended importantly on their abilities to mobilize cavalry. Centralization of the southern states accelerated with access to the Atlantic trade and to firearms.

History

The documented early states of the western savanna arose at the southern termini of the trans-Saharan trade routes, largely along the River Niger, at 2,600 miles the major river of West Africa. Ghana, in the west, and Kanem near Lake Chad, were known to Arab geographers before AD 1000. The Empire of Mali, dominated by Mande-speakers, reached its apogee in the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, leaving a profound historical and artistic legacy in the western savanna. Its successor state, Songhai, collapsed in 1591 as a result of Moroccan invasion. The Mossi states (Burkina Faso) rose to power in the fifteenth century, while to their east the Hausa (Nigeria and Niger) lived in numerous city states. Savanna society was marked by distinctions of rank (especially in the west) and ethnicity, under the influence of Islam. From the late eighteenth century, in the course of an Islamic holy war (jihad) under the Fulani leadership of Uthman dan Fodio, emirates were created in Hausaland and beyond which together formed the Sokoto Caliphate, the most extensive political formation in West Africa at colonialization. This example was followed by Sheikh Hamadu and al-Hajj Umar who established Islamic states in the western savanna during the nineteenth century.

The forest and forest margins included both relatively uncentralized societies and well-organized states. The kingdoms of Benin and Ife were powerful before European coastal contacts became increasingly important from the mid-fifteenth century. The export of slaves against imports of firearms and other trade goods reoriented both economics and politics. Kingdoms which became powerful between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries — including Asante (Ghana), Dahomey (Benin), Oyo (Nigeria) — as well as the city states which arose along the coast, competed with their neighbours to control the wealth to be accrued from the Atlantic trade.

Throughout the savanna and forest regions, and between them, societies of smaller scale than kingdoms were able to resist incorporation by virtue of some combination of their military organization, inaccessibility, and strategic alliances. The internal organization of these societies probably differed even more widely than the centralized societies. Thus, the colonies established when European nations extended their influence beyond the coast during the ‘scramble for Africa’ in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, consisted of peoples whose diversity posed challenges to colonial and later national governments.

Ethnographic writing: colonial traditions

Historical understanding of West Africa derives from archaeological investigations, oral traditions,the records of Arab travellers and African intellectuals, and, for the last four centuries, the writings of European travellers, explorers, traders and missionaries. From the late nineteenth century, these accounts became more systematic. The establishment of colonial rule in British colonies under the principle of "’ indirect rule’ — that where possible African political institutions and customs should form the basis of colonial administration — created a requirement for documentation that was met in several ways: from the enquiries of European administrators with varying degrees of anthropological training, by the employment of official government anthropologists (e.g. "R.S. Rattray in Ghana; C.K. Meek, H.F. Matthews and R.C. Abraham in Nigeria), and — probably to a less significant degree — from academic anthropologists. The characteristics of the work of anthropologists derived from the conjunction of colonial, indirect rule, which made research possible and necessary, the ascendancy of structural func-tionalism in British anthropology, the foundation of — what is now — the "International African Institute in 1926 under the headship of Lugard, and the ability of this institute to secure funding in significant amounts — especially from such American patrons as the Rockefeller Foundation.

‘French’ and ‘British’ traditions of ethnographic writing developed largely with respect to their colonial possessions with theoretical agendas that appear distinctive in retrospect. Africanists predominated among professional anthropologists at the same period, with the result that issues of particular concern to the regional study of Africa enjoyed a prominent position within British and French anthropology more generally.

The British tradition was especially concerned with the sociological description of tribes and chiefdoms or states. In practice this meant amassing detailed documentation on patterns of residence, kinship, lineage, membership, inheritance and marriage that were held to explain the normal functioning of local units. Larger scale political formations were usually investigated in terms of the enduring features of their organization. The landmark collection African Political Systems (Fortes and Evans-Pritchard 1940) defined the field of political anthropology for a generation. It included analyses of the Tallensi of northern Ghana, which became a classic instance of an uncentralized society in West Africa (Fortes 1949; Fortes and Horton 1983), and of the Nupe kingdom in Nigeria, about which S.F. Nadel wrote an enduring masterpiece of West Africanist ethnography (Nadel 1942). Under the guidance of "Meyer Fortes and then Jack Goody, Cambridge became the major centre for Ghanaian studies in Britain. Like Fortes who also studied the Asante, Goody worked in both centralized and uncentralized societies, producing his most detailed descriptions of the uncentralized LoDagaa. University College London, under the headships of "Daryll Forde, whose ethnography concerned the Yako of southeastern Nigeria, and then M.G. Smith, who wrote widely on the Emirates of northern Nigeria. became closely associated with studies in history, politics, economics and ecology — initially in Nigeria and later more widely. A nexus of interests in Sierra Leone developed in Edinburgh where Kenneth Little, James Lit-tlejohn and Christopher Fyfe all taught. Not all ‘British’ West Africanist research emanated from these three centres — the influential work of the Oxford-trained Americans Laura and Paul Bohannan on the "acephalous Nigerian Tiv is a clear "exception – but these institutional specializations remained powerful beyond the period of African Independence. The literature of this period has attracted criticisms for its aim to reconstruct the lives of West African societies prior to colonialization, its relative neglect of contemporary events, normative bias consistent with the needs of indirect rule, reliance on male informants, and tendency to reify tribal units. This critique forms part of a general reaction to structural-functionalism, but is not equally applicable to all writers on West Africa before the mid-1960s.

The French tradition of the same period -exemplified by the written work of M. Griaule and "G. Dieterlen (1991) and their collaborators on Dogon and Bambara, and by the films of J. Rouch – was particularly concerned with the study of religion and cosmology among non-Muslim peoples of the western savanna. However, other writers shared the ‘British’ concern with the documentation of social organization, as for instance M. Dupire’s classic studies of Fulani. More recently, the application of Levi-Straussian alliance theory has been a relatively distinctive French interest.

An American tradition, cued in part by an interest in African cultures in the New World diaspora, can be identified in MJ. Herskovits’s study of Dahomey, and in the work of his student W.R. Bascom on Yoruba.

Ethnographic writing: contemporary interests

Ethnographic research in West Africa is no less susceptible to simple summary. The French and British schools have lost much of their distinc-tiveness; considerable American interest has cut across the old association between national and colonial traditions; and, more generally, the disciplinary boundaries between the different social sciences and humanities have become extremely porous in relation to West Africa. Much of this is due to the writings of African scholars critical of anthropology’s colonial associations (Ajayi 1965). Two recontextualizations are striking: a turn from ethnographic reconstruction to a historical appreciation of changes in West African societies (evident in M.G. Smith’s works on Hausa, J.D.Y. Peel’s on Yoruba, or Claude Tardits’s on Bamun), and treatment of African peoples in regional and intercontinental perspectives. Researches into some of the larger groups of West African peoples, notably Akan-Twi, Hausa, Mande and Yoruba speakers, have become developed specializations demanding high levels of language proficiency and familiarity with diaspora issues in Africa and beyond.

The person in West Africa: vigorous interest in ideas of the person in West Africa has been shared by American, British and French ethnographers. In part, this has involved rethinking topics previously dealt with as kinship, marriage, descent, family organization, slavery and pawn-ship to question ideas of sociality that constitute the person. But the interest also draws upon contemporary debates concerning gender, religion, and the politics of identity (Fortes and Horton 1983; Jackson 1989; Oppong 1983). Specialists in art, performance studies and literature have contributed significantly to this debate.

Inequality: the problems faced by West African states since independence have prompted contemporary studies of inequality and poverty examining the rapid rate of urbanization in West Africa, development of the ‘informal economy’ (K. Hart’s term), linkages between the state and local communities as well as the dynamics of ethnicity, to which anthropologists have contributed detailed local studies.

West African agriculture:: West Africa remains lightly industrialized so that a majority of the population continues to earn a livelihood from agriculture or from trade. French structural Marxist approaches to the analysis of African modes of production gave general impetus to re-examination of the nature of African agriculture from the mid-1960s (Meillassoux 1981). Subsequently, problems of food and cash crop production in African countries, the poor performance of development interventions in improving the agricultural sector, the political sensitivity of food prices in urban areas, and the impact of structural adjustment policies have underlined the significance of agriculture. Ethnographic investigations have emphasized issues of household composition, gender roles and indigenous agricultural knowledge (Richards 1985).

Religion and conversion: interest in both local and world religions has several strands. These include debates over the nature and explanation of ‘conversion’ (following Horton’s hypotheses), the growth of separatist churches, the expansion of Islam, and concern with local religions especially in the contexts of studies of art and performance and the roles of African religions in the diaspora.

Representation of West Africa: vigorous debates have developed around the depiction of West Africa and West African peoples in words and images. Issues of authenticity and authority have been raised in relation to philosophy, African languages, fiction and autobiography, history and ethnography, oral literature and literature (Appiah 1992).