Epidemiology

Estimates of the prevalence of PsA among individuals with psoriasis range from 5 to 30%. In Caucasian populations, psoriasis is estimated to have a prevalence of 1-3%. Psoriasis and PsA are less common in other races in the absence of HIV infection. First-degree relatives of PsA patients have an elevated risk for psoriasis, for PsA itself, and for other forms of spondyloarthritis. Of patients with psoriasis, 30% have an affected first-degree relative. In monozygotic twins, the concordance for psoriasis is >65%, and for PsA >30%.A variety of HLA associations have been found.The HLA-Cw6 gene is directly associated with psoriasis, particularly familial juvenile onset (type I) psoriasis. HLA-B27 is associated with psoriatic spondylitis (see below). HLA-DR7, -DQ3, and -B57 are associated with PsA because of linkage disequilibrium with Cw6. Other associations include HLA-B13, -B37, -B38, -B39, and DR4. The MIC-A-A9 allele at the HLA-B-linked MIC-A locus has also recently been reported associated with PsA, as have certain killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) alleles. The complex inheritance patterns of psoriasis and PsA suggest that several unlinked allelic loci are required for susceptibility. However, only the MHC has shown consistent linkage from study to study.

Pathology

The inflamed synovium in PsA resembles that of RA, although with somewhat less hyperplasia and cellularity than in RA, and somewhat greater vascularity. Some studies have indicated a higher tendency to synovial fibrosis in PsA. Unlike RA, PsA shows prominent enthesitis, with histology similar to that of the other spondyloarthritides.

Pathogenesis

PsA is almost certainly immune mediated and probably shares pathogenic mechanisms with psoriasis. PsA synovium shows infiltration with T cells, B cells, macrophages, and natural killer (NK) receptor-expressing cells, with upregu-lation of leukocyte homing receptors. Clonally expanded CD8+ T cells are frequent in PsA. Cytokine production in the synovium in PsA resembles that in psoriatic skin lesions and in RA synovium, having predominantly a TH1 pattern. Interleukin (IL) 2, interferon γ,TNF-α, and IL-1ß, -6, -8, -10, -12, -13, and -15 are found in PsA synovium or synovial fluid. Consistent with the extensive bone lesions in PsA, patients with PsA have been found to have a marked increase in osteoclastic precursors in peripheral blood and upregulation of RANKL (receptor activator of NF-κβ ligand) in the synovial lining layer.

Clinical Features

In 60-70% of cases, psoriasis precedes joint disease. In 15-20%, the two manifestations appear within 1 year of each other. In about 15-20% of cases, the arthritis precedes the onset of psoriasis and can present a diagnostic challenge. The frequency in men and women is almost equal, although the frequency of disease patterns differs somewhat in the two sexes. The disease can begin in childhood or late in life but typically begins in the fourth or fifth decade, at an average age of 37 years.

The spectrum of arthropathy associated with psoriasis is quite broad. Many classification schemes have been proposed. In the original scheme of Wright and Moll, five patterns are described: (1) arthritis of the DIP joints; (2) asymmetric oligoarthritis; (3) symmetric polyarthritis similar to RA; (4) axial involvement (spine and sacroiliac joints); and (5) arthritis mutilans, a highly destructive form of disease. These patterns are not fixed, and the pattern that persists chronically often differs from that of the initial presentation. A simpler scheme in recent use contains three patterns: oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, and axial arthritis.

Nail changes in the fingers or toes occur in 90% of patients with PsA, compared with 40% of psoriatic patients without arthritis, and pustular psoriasis is said to be associated with more severe arthritis. Several articular features distinguish PsA from other joint disorders. Dactylitis occurs in >30%; enthesitis and tenosynovitis are also common and are probably present in most patients although often not appreciated on physical examination. Shortening of digits because of underlying osteolysis is particularly characteristic of PsA, and there is a much greater tendency than in RA for both fibrous and bony ankylosis of small joints. Rapid ankylosis of one or more proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints early in the course of disease is not uncommon. Back and neck pain and stiffness are also common in PsA.

Arthropathy confined to the DIP joints predominates in about 15% of cases. Accompanying nail changes in the affected digits are almost always present.Thesejoints are also often affected in the other patterns of PsA.Approximately 30% of patients have asymmetric oligoarthritis. This pattern commonly involves a knee or another large joint with a few small joints in the fingers or toes, often with dactylitis. Symmetric polyarthritis occurs in about 40% of PsA patients at presentation. It may be indistinguishable from RA in terms of the joints involved, but other features characteristic of PsA are usually also present. In general, peripheral joints in PsA tend to be somewhat less tender than in RA, although signs of inflammation are usually present. Almost any peripheral joint can be involved. Axial arthropathy without peripheral involvement is found in about 5% of PsA patients. It may be indistinguishable from idiopathic AS, although more neck involvement and less thoracolumbar spinal involvement is characteristic, and nail changes are not found in idiopathic AS. About 5% of PsA patients have arthritis mutilans, in which there can be widespread shortening of digits (“telescoping”), sometimes coexisting with ankylosis and contractures in other digits.

Six patterns of nail involvement are identified: pitting, horizontal ridging, onycholysis, yellowish discoloration of the nail margins, dystrophic hyperkeratosis, and combinations of these findings. Other extraarticular manifestations of the spondyloarthritides are common. Eye involvement, either conjunctivitis or uveitis, is reported in 7-33% of PsA patients. Unlike the uveitis associated with AS, the uveitis in PsA is more often bilateral, chronic, and/or posterior. Aortic valve insufficiency has been found in <4% of patients, usually after long-standing disease.

Widely varying estimates of clinical outcome have been reported in PsA. At its worst, severe PsA with arthritis mutilans is at least as crippling and ultimately fatal as severe RA. Unlike RA, however, many patients with PsA experience temporary remissions. Overall, erosive disease develops in the majority of patients, progressive disease with deformity and disability is common, and in some large published series, mortality was found to be significantly increased compared with the general population.

The psoriasis and associated arthropathy seen with HIV infection both tend to be severe and can occur in populations with very little psoriasis in noninfected individuals. Severe enthesopathy, dactylitis, and rapidly progressive joint destruction are seen, but axial involvement is very rare. This condition is prevented by or responds well to antiretroviral therapy.

Laboratory and Radiographic Findings

There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for PsA. ESR and CRP are often elevated. A small percentage of patients may have low titers of rheumatoid factor or antinuclear antibodies. Uric acid may be elevated in the presence of extensive psoriasis. HLA-B27 is found in 50-70% of patients with axial disease, but ^15-20% in patients with only peripheral joint involvement.

The peripheral and axial arthropathies in PsA show a number of radiographic features that distinguish them from RA and AS, respectively. Characteristics of peripheral PsA include DIP involvement, including the classic “pencil-in-cup” deformity; marginal erosions with adjacent bony proliferation (“whiskering”); small-joint ankylosis; osteolysis of phalangeal and metacarpal bone, with telescoping of digits; and periostitis and proliferative new bone at sites of enthesitis (Fig. 9-3). Characteristics of axial PsA include asymmetric sacroiliitis; compared with idiopathic AS, less zygoapophyseal joint arthritis, fewer and less symmetric and delicate syndesmophytes; fluffy hyperperiostosis on anterior vertebral bodies; severe cervical spine involvement, with a tendency to atlantoaxial subluxation but relative sparing of the thoracolumbar spine; and paravertebral ossification. Ultrasound and MRI both readily demonstrate enthesitis and tendon sheath effusions that can be difficult to assess on physical examination. A recent MRI study of 68 PsA patients found sacroiliitis in 35%, unrelated to B27 but correlated with restricted spinal movement.

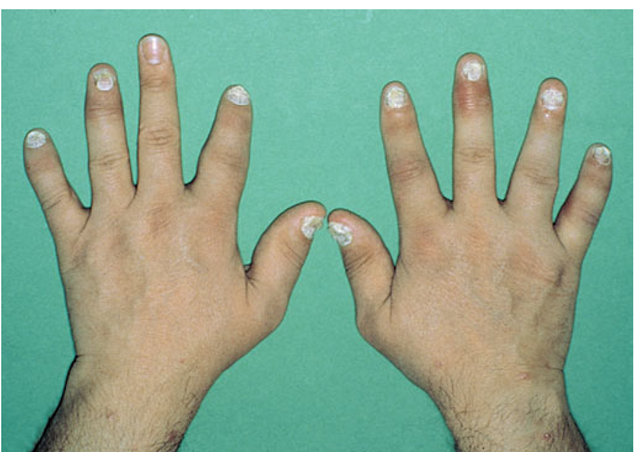

FIGURE 9-3

Characteristic lesions of psoriatic arthritis. Inflammation is prominent in the DIP joints (left 5th, 4th, 2nd; right 3rd and 5th) and PIP joints (left 2nd, right 2nd, 4th, and 5th). There is dactylitis in the left 2nd finger and thumb, with pronounced telescoping of the left 2nd finger. Nail dystrophy (hyperkeratosis and onycholysis) affects each of the fingers except the left 3rd finger, the only finger without arthritis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PsA is primarily clinical, based on the presence of psoriasis and characteristic peripheral or spinal joint symptoms, signs, and imaging. Diagnosis can be challenging when the arthritis precedes psoriasis, the psoriasis is undiagnosed or obscure, or the joint involvement closely resembles another form of arthritis. A high index of suspicion is needed in any patient with an undiagnosed inflammatory arthropathy. The history should include inquiry about psoriasis in the patient and family members. Patients should be asked to disrobe for the physical examination, and psoriasiform lesions should be sought in the scalp, ears, umbilicus, and gluteal folds in addition to more accessible sites; the finger and toe nails should also be carefully examined. Axial symptoms or signs, dactylitis, enthesitis, ankylosis, the pattern ofjoint involvement, and characteristic radiographic changes can be helpful clues. The differential diagnosis of isolated DIP involvement is short. Osteoarthritis (Heberden’s nodes) is usually not inflammatory; gout involving more than one DIP joint often involves other sites and is accompanied by tophi; the very rare entity multicentric reticulohistiocytosis involves other joints and has characteristic small pearly periungual skin nodules; and the uncommon entity inflammatory osteoarthritis,like the others,lacks the nail changes of PsA. Radiography can be helpful in all of these cases and in distinguishing between psoriatic spondylitis and idiopathic AS. A history of trauma to an affected joint preceding the onset of arthritis is said to occur more frequently in PsA than in other types of arthritis, perhaps reflecting the Koebner phenomenon in which psoriatic skin lesions can arise at sites of the skin trauma.

Treatment:

Psoriatic Arthritis

Ideally, coordinated therapy is directed at both the skin and joints in PsA. As described above for AS, use of the anti-TNF-α agents has revolutionized the treatment of PsA. Prompt and dramatic resolution of both arthritis and skin lesions has been observed in large, randomized controlled trials of etanercept, infliximab, and adali-mumab. Many of the responding patients had longstanding disease that was resistant to all previous therapy, as well as extensive skin disease. The clinical response is more dramatic than in RA, and delay of disease progression has been demonstrated radiographi-cally.The anti-T cell biologic agent Alefacept, in combination with methotrexate, has also been proven effective in both psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis.

Other treatment for PsA has been based on drugs that have efficacy in RA and/or in psoriasis. Although methotrexate in doses of 15-25 mg/week and sulfasalazine (usually given in doses of 2-3 g/d) have each been found to have clinical efficacy in controlled trials, neither effectively halts progression of erosive joint disease. Other agents with efficacy in psoriasis reported to benefit PsA are cyclosporine, retinoic acid derivatives, and psoralen plus ultraviolet light (PUVA).There is controversy regarding the efficacy in PsA of gold and anti-malarials, which have been widely used in RA. The pyrimidine synthetase inhibitor leflunomide has been shown in a randomized controlled trial to be beneficial in both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

All of these treatments require careful monitoring. Immunosuppressive therapy may be used cautiously in HIV-associated PsA if the HIV infection is well controlled.

In one large prospective series, 7% of patients with PsA required musculoskeletal surgery beginning at a mean of 13 years’disease duration. Indications for surgery are similar to those in RA, although there is an impression that outcomes in PsA may be less satisfactory.

Undifferentiated and Juvenileonset Spondyloarthritis

Many patients, usually young adults, present with some features of one or more of the spondyloarthritides discussed above but lack criteria for these diagnoses. For example, a patient may present with inflammatory synovitis of one knee, Achilles tendinitis, and dactylitis of one digit, or sacroiliitis in the absence of other criteria for AS. Such patients are said to have undifferentiated spondyloarthritis, or simply spondyloarthritis, as defined by the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG criteria, Fig. 9-4). Some of these patients may have ReA in which the triggering infection remains clinically silent. In other cases, the patient subsequently develops IBD or psoriasis or the process eventually meets criteria for AS. Approximately half the patients with undifferentiated spondyloarthritis are HLA-B27 positive, and thus the absence of B27 is not useful in establishing or excluding the diagnosis. In familial cases, which are much more frequently B27 positive, there is often eventual progression to AS.

FIGURE 9-4

Algorithm for diagnosis of the spondyloarthritides, adapted from the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group criteria and the Amor criteria (M Dougados et al: Arthritis Rheum 34:1218, 1991; B Amor: Rev Rhum Mal Ostéoartic 57:85, 1990). Sensitivity and specificity for any given decision armare approximately 80%. If a diagnosis of psoriatic arthropathy, reactive arthritis, or undifferentiated spondyloarthritis is made on the basis of peripheral arthropathy, then HIV infection needs to be considered.

In juvenile-onset spondyloarthritis, which begins between ages 7 and 16, most commonly in boys (60-80%), an asymmetric, predominantly lower-extremity oligoarthritis and enthesitis without extraarticular features is the typical mode of presentation. The prevalence of B27 in this condition, which has been termed the seronegative, enthe-sopathy, arthropathy (SEA) syndrome, is approximately 80%. Many, but not all, of these patients go on to develop AS in late adolescence or adulthood.

Management of undifferentiated spondyloarthritis is similar to that of the other spondyloarthritides. Response to anti-TNF-α therapy has been documented, and this therapy is indicated in severe, persistent cases not responsive to other treatment. One recent study reported significant benefit in patients with long-standing undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy treated for 9 months with doxycy-cline and rifampin.These data await confirmation.

Enteropathic Arthritis

Historic Background

A relationship between arthritis and IBD was observed in the 1930s.The relationship was further defined by the epidemiologic studies in the 1950s and 1960s and included in the concept of the spondyloarthritides in the 1970s.

Epidemiology

Both of the common forms of IBD, ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), are associated with spondyloarthritis. UC and CD both have an estimated prevalence of 0.05-0.1%, and the incidence of each is thought to have increased in recent decades. AS and peripheral arthritis are both associated with UC and with CD. Wide variations have been reported in the estimated frequencies of these associations. In recent series, AS was diagnosed in 1-10%, and peripheral arthritis in 10-50%, of patients with IBD. Inflammatory back pain and enthe-sopathy are common, and many patients have sacroiliitis on imaging studies.

The prevalence of UC or CD in patients with AS is thought to be 5-10%. However, investigation of unselected spondyloarthritis patients by ileocolonoscopy has revealed that from one-third to two-thirds of patients with AS have subclinical intestinal inflammation that is evident either macroscopically or histologically. These lesions have also been found in patients with undifferentiated spondyloarthritis or ReA (both enterically and urogenitally acquired).

Both UC and CD have a tendency to familial aggregation, more so for CD. HLA associations have been weak and inconsistent. HLA-B27 is found in up to 70% of patients with IBD and AS, but in <15% of patients with IBD and peripheral arthritis or IBD alone. Three alleles of the NOD2/CARD15 gene on chromosome 16 have been found in approximately half of patients with CD. These alleles are not associated with the spondyloarthritides per se. However, they are found significantly more often in (1) CD patients with sacroiliitis than in those without sacroiliitis, and (2) SpA patients with chronic inflammatory gut lesions than in those with normal gut histology. These associations are independent of HLA-B27.

Pathology

Available data for IBD-associated peripheral arthritis suggest a synovial histology similar to other spondyloarthri-tides. Association with arthropathy does not affect the gut histology of UC or CD. The subclinical inflammatory lesions in the colon and distal ileum associated with spondyloarthritis have been classified as either acute or chronic. The former resemble acute bacterial enteritis, with largely intact architecture and neutrophilic infiltration in the lamina propria. The latter resemble the lesions of CD, with distortion of villi and crypts, aphthoid ulceration, and mononuclear cell infiltration in the lamina propria.

Pathogenesis

Both IBD and the spondyloarthropathies are immune mediated, but the specific pathogenic mechanisms are poorly understood, and the connection between the two is obscure. IBD is a common phenotype in a number of rodent lines with transgenic overexpression or targeted deletion of genes involved in immune processes. Arthritis is an accompanying prominent feature in two of these IBD models, HLA-B27 transgenic rats and mice with constitutive overexpression of TNF-α, and immune dysregulation is prominent in both. Several lines of evidence indicate trafficking of leukocytes between the gut and the joint. Mucosal leukocytes from IBD patients have been shown to bind avidly to synovial vasculature through several different adhesion molecules. Macrophages expressing CD163 are prominent in the inflammatory lesions of both gut and synovium in the spondyloarthritides.

Clinical Features

AS associated with IBD is clinically indistinguishable from idiopathic AS. It runs a course independent of the bowel disease, and in many patients it precedes the onset of IBD, sometimes by many years. Peripheral arthritis not infrequently begins before onset of overt bowel disease. The spectrum of peripheral arthritis includes acute self-limited attacks of oligoarthritis that often coincide with relapses of IBD, and more chronic and symmetric polyarticular arthritis that runs a course independent of IBD activity.The patterns of joint involvement are similar in UC and CD. In general, erosions and deformities are infrequent in IBD-associated peripheral arthritis, and joint surgery is rarely required. Dactylitis and enthesopathy are occasionally found. In addition to the ~20% of IBD patients with spondyloarthritis, a comparable percentage have arthralgias or fibromyalgia symptoms.

Other extraintestinal manifestations of IBD are seen in addition to arthropathy, including uveitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and finger clubbing, all somewhat more common in CD than UC. The uveitis shares the features described above for PsA-associated uveitis.

Laboratory and Radiographic Findings

Laboratory findings reflect the inflammatory and metabolic manifestations of IBD.Joint fluid is usually at least mildly inflammatory. Of patients with AS and IBD, 30-70% carry the HLA-B27 gene, compared with >90% of patients with AS alone and 50-70% of those with AS and psoriasis. Hence, definite or probable AS in a B27-negative individual in the absence of psoriasis should prompt a search for occult IBD. Radiographic changes in the axial skeleton are the same as in uncomplicated AS. Erosions are uncommon in peripheral arthritis but may occur, particularly in the metatarsophalangeal joints. Isolated destructive hip disease has been described.

Diagnosis

Diarrhea and arthritis are both common conditions that can coexist for a variety of reasons.When etiopathogeni-cally related, reactive arthritis and IBD-associated arthritis are the most common causes. Rare causes include celiac disease, blind loop syndromes, and Whipple’s disease. In most cases, diagnosis depends upon investigation of the bowel disease.

Treatment:

Enteropathic Arthritis

As with the spondyloarthritides, treatment of CD has been revolutionized by therapy with anti-TNF agents. Infliximab and adalimumab are effective for induction and maintenance of clinical remission in CD, and infliximab has been shown to be effective in fistulizing CD.

IBD-associated arthritis also responds to these agents. Other treatment for IBD, including sulfasalazine and related drugs, systemic glucocorticoids, and immunosuppressive drugs, are also usually of benefit for associated peripheral arthritis. NSAIDs are generally helpful and well tolerated, but they can precipitate flares of IBD.

Sapho Syndrome

The syndrome of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) is characterized by a variety of skin and musculoskeletal manifestations. Dermatologic manifestations include palmoplantar pustulosis, acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and hidradenitis suppurativa. The main musculoskeletal findings are sternoclavicular and spinal hyperostosis, chronic recurrent foci of sterile osteomyelitis, and axial or peripheral arthritis. Cases with one or a few manifestations are probably the rule. The ESR is usually elevated, sometimes dramatically. In some cases, bacteria, most often Propionibacterium acnes, have been cultured from bone biopsy specimens and occasionally other sites. Inflammatory bowel disease was coexistent in 8% of patients in one large series. B27 is found in only a small minority of patients. Either bone scan or CT scan is helpful diagnostically. High-dose NSAIDs may provide relief from bone pain. A number of uncontrolled series and case reports of successful therapy with pamidronate or other bisphosphonates have appeared recently. Response to anti-TNF-α therapy has also been observed, although in a few cases this has been associated with a flare of skin manifestations. Successful prolonged antibiotic therapy has also been reported.

Whipple’s Disease

Whipple’s disease is a rare chronic bacterial infection, mostly of middle-aged Caucasian men, caused by Tropheryma whippelii. At least 75% of affected individuals develop an oligo- or polyarthritis. The joint manifestations usually precede other symptoms of the disease by 5 years or more; they are thus particularly important because antibiotic therapy is curative, whereas the untreated disease is fatal. Large and small peripheral joints and sacroiliac joints may be involved. The arthritis is abrupt in onset, migratory, usually lasts hours to a few days, and then resolves completely. Chronic polyarthritis and joint space loss, visible on x-ray, can occur but are not typical. Eventually prolonged diarrhea, malabsorption, and weight loss occur. Other manifestations of systemic disease include fever, edema, serositis, endocarditis, pneumonia, hypotension, lymphadenopathy, hyperpigmentation, subcutaneous nodules, clubbing, and uveitis. Central nervous system involvement eventually develops in 80% ofuntreated patients, with cognitive changes, headache, diplopia, and papilledema, and may be appreciated by abnormalities on MRI. Oculomasticatory and oculo-facial-skeletal myorhythmia, accompanied by supranuclear vertical gaze palsy, are said to be pathognomonic. Laboratory abnormalities include anemia and changes from malabsorption. There is at most a weak association with HLA-B27. Synovial fluid is usually inflammatory. Radiography rarely shows joint erosions but may show sacroiliitis. Abdominal CT may reveal lymphadenopathy. Foamy macrophages containing periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-staining bacterial remnants can be seen in biopsies of small intestine, synovium, lymph node, and other tissues.

The complete genome sequence of T whippelii was published in 2003. Diagnosis is established by PCR amplification of sequences of the 16S ribosomal gene or other genes of T. whippelii in biopsied tissue. In the future, this may be supplanted or complemented by serologic tests. The syndrome responds best to therapy with penicillin (or ceftriaxone) and streptomycin for 2 weeks followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 1-2 years. Monitoring for central nervous system relapse is critical.