Prognosis

The risk of death or loss of organ function remains low in sarcoidosis. Poor outcomes usually occur in patients who present with advanced disease in whom treatment seems to have little impact. In these cases, irreversible fibrotic changes have frequently occurred.

For the majority of patients, initial presentation occurs during the granulomatous phase of the disease as depicted in Fig. 13-1. It is clear that many patients resolve their disease within 2-5 years. These patients are felt to have acute, self-limiting sarcoidosis. On the other hand, there is a form of the disease that does not resolve within the first 2-5 years. These chronic patients can be identified at presentation by certain risk factors at presentation such as fibrosis on chest roentgenogram, presence of lupus pernio, bone cysts, cardiac or neurologic disease (except isolated seventh nerve paralysis), and presence of renal calculi due to hypercalciuria. Recent studies also indicate that patients who require glucocorticoids for any manifestation of their disease in the first 6 months of presentation have a >50% chance of having chronic disease. In contrast, <10% of patients who require systemic therapy in the first 6 months will require chronic therapy.

Treatment:

Sarcoidosis

The indications for therapy should be based on symptoms. The patient with elevated liver function tests or an abnormal chest roentgenogram probably does not benefit from treatment. However, these patients should be monitored for evidence of progressive, symptomatic disease.

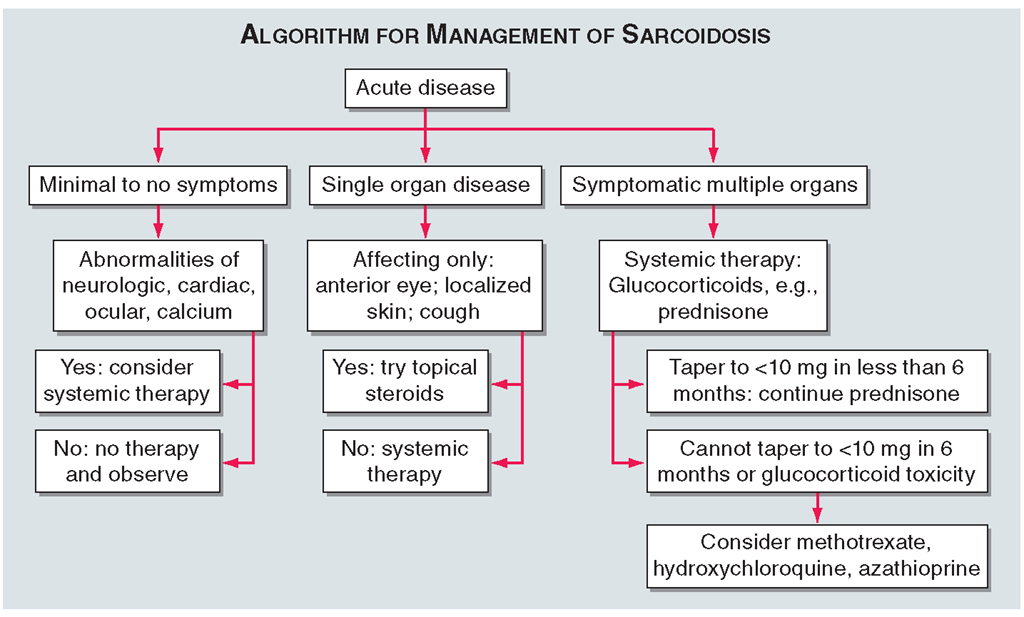

One approach to therapy is summarized in Figs.13-9 and 13-10.We have divided the approach into treating acute versus chronic disease. For acute disease, no therapy remains a viable option for patients with no or mild symptoms. For symptoms confined to only one organ, topical therapy is preferable. For multiorgan disease or disease too extensive for topical therapy, an approach to systemic therapy is outlined.

FIGURE 13-9

The management of acute sarcoidosis is based on level of symptoms and extent of organ involvement. In patients with mild symptoms, no therapy may be needed unless specified manifestations are noted.

FIGURE 13-10

Approach to chronic disease is based on whether glucocorticoid therapy is tolerated or not.

Glucocorticoids remain the drugs of choice for this disease. However, the decision to continue to treat with glucocorticoids or to add steroid-sparing agents depends on the tolerability, duration, and dosage of glucocorticoids. Table 13-2 summarizes the dosage and monitoring of several commonly used drugs. According to the available trials, evidence-based recommendations are made. Most of these recommendations are for pulmonary disease because most of the trials were performed only in pulmonary disease.Treatment recommendations for extra-pulmonary disease are usually similar with a few modifications. For example, the dosage of glucocorticoids is usually higher for neurosarcoidosis and lower for cutaneous disease.There was some suggestion that higher doses would be beneficial for cardiac sarcoidosis, but one study found that initial doses >40 mg/d prednisone were associated with a worse outcome.

TABLE 13-2

|

COMMONLY USED DRUGS TO TREAT SARCOIDOSIS |

||||||

|

DRUG |

INITIAL DOSE |

MAINTENANCE DOSE |

MONITORING |

TOXICITY |

SUPPORT THERAPYa |

SUPPORT MONITORINGa |

|

Prednisone |

20-40 |

Taper to |

Glucose, blood pressure, bone density |

Diabetes, |

A: Acute pulmonary |

|

|

mg qd |

5-10 mg |

osteoporosis |

D: Extrapulmonary |

|||

|

Hydroxychlo roquine |

200-400 mg qd |

400 mg qd |

Eye exam q6-12 mo |

Ocular |

B: Some forms of disease |

D: Routine eye exam |

|

Methotrexate |

10 mg qw |

2.5-15 mg qw |

CBC, renal, hepatic q2mo |

Hematologic, nausea, hepatic, pulmonary |

B: Steroid sparing C: Some forms chronic disease |

D: Routine hematologic, renal, and hepatic monitoring |

|

Azathioprine |

50-150 mg qd |

50-200 mg qd |

CBC, renal q2mo |

Hematologic, nausea |

C: Some forms chronic disease |

D: Routine hematologic monitoring |

|

Infliximab |

3-5 mg/kg q2wk for 2 doses |

3-10 mg/kg q4-8 wk |

Initial PPD |

Infections, allergic reaction, carcinogen |

B: Chronic pulmonary disease |

C: Caution in patients with latent tubercu losis or advanced congestive heart failure |

aGrade A: supported by at least two double-blind randomized control trials; grade B: supported by prospective cohort studies; grade C: supported primarily by two or more retrospective studies; grade D: only one retrospective study or based on experience in other diseases.

Note: CBC, complete blood count; PPD, purified protein derivative test for tuberculosis.

While most patients receive glucocorticoids as their initial systemic therapy, toxicity associated with prolonged therapy often leads to steroid-sparing alterna-tives.The antimalarial drugs such as hydroxychloroquine are more effective for skin than pulmonary disease. Minocycline may also be useful for cutaneous sarcoidosis. For pulmonary and other extrapulmonary disease, cytotoxic agents are often employed. These include methotrexate,azathioprine,chlorambucil,and cyclophosphamide. The most widely studied cytotoxic agent has been methotrexate. This agent works in approximately two-thirds of sarcoidosis patients, regardless of the disease manifestation.As noted in Table 13-2,specific guidelines for monitoring therapy have been recommended. Cytokine modulators such as thalidomide and pentoxifylline have also been used in a limited number of cases.

The anti-TNF agents have recently been studied in sar-coidosis,with prospective randomized trials of both etaner-cept and infliximab completed. Etanercept has a limited role as a steroid-sparing agent. On the other hand, infliximab significantly improves lung function when given to patients with chronic disease already on glucocorticoids and cytotoxic agents.The difference in response for these two agents is similar to that observed in Crohn’s disease, where infliximab is effective and etanercept is not. In addition, increased risks for reactivation of tuberculosis are reported for infliximab compared to etanercept.The differential response rate could be explained by differences in mechanism of action since etanercept is a TNF receptor antagonist and infliximab is a monoclonal antibody against TNF. The peak dosage of the drug may also be different, since etanercept is given SC whereas infliximab is given IV. A higher peak dose may lead to better intracellular penetration and therefore affect the transmembrane TNF. In contrast to etanercept, infliximab binds to TNF on the surface of some cells that are releasing TNF and this can lead to cell lysis.This effect has been documented in Crohn’s disease.

The role of the newer therapeutic agents for sarcoidosis is still evolving. However, these targeted therapies confirm that TNF may be an important target, especially in the treatment of chronic disease. However,the majority of cases either do not require therapy or can be controlled with glucocorticoids and cytotoxic agents.