INTRODUCTION

The ability of a company to be innovative depends on many factors, such as a culture amenable to risk taking (Kontoghior-ghes,Awbre, & Feurig, 2005), a managerial attitude favorable toward change (Damanpour, 1991), a market orientation (Hult, Hurley, & Knight, 2004), committed champions (Howell, 2005), and an adequate supply of physical and financial resources for research (Delbecq & Mills, 1985). In addition, the innovation process requires organizational and technical competences in knowledge management, collaboration, and communication (Carneiro, 2000; McAdam, 2000; Zakaria, Amelinckx, & Wilemon, 2004,). Corporate portals are central to achieving these competences. This article describes how corporate portals can support innovation in organizations through the enhancement of knowledge management, communication, and collaboration.

BACKGROUND

Innovation is one of the primary drivers of corporate growth and profitability. Research shows that innovations generate supernormal profits for the companies that create them, but that these profits erode over time in response to competitive imitation (Geroski, Machin, & Van Reenan, 1993). Yet, some firms have the ability to innovate constantly, generating multiple innovations to maintain supernormal profits in the face of competitive responses (Cho & Pucik, 2005). Because the ability to innovate constantly is so desirable, researchers have sought to understand the antecedents of innovation, that is, the characteristics that underlie and support an innovation competency for individuals and organizations (for example, Hult et al., 2004; Scott & Bruce, 1994).

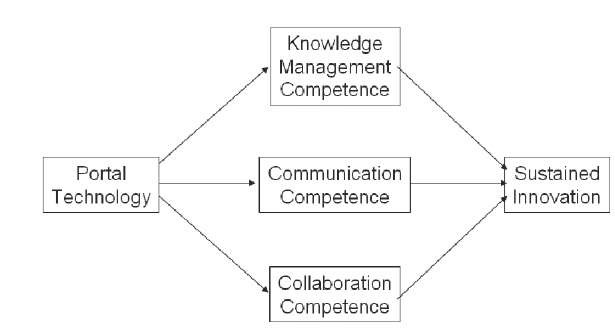

The modern resource-based view of the firm posits that a company can achieve a competitive advantage by coordinating and combining the resources under its control to achieve competences or capabilities that align with its strategic vision (Freiling, 2004). From this perspective, a firm’s competence in innovation depends on its other competences, and on the resources it can marshal toward the innovation objective (Pitt & Clarke, 1999). Specifically, as described next, three competences, knowledge management, communication, and collaboration, are particularly important and necessary for supporting the innovation process. We show that portal technologies help build and maintain these competencies, contributing indirectly to a sustained innovation capability (see Figure 1).

Knowledge Management

A competence in knowledge management is critical to successful innovation because innovation is a knowledge-intensive process (Gloet & Terziovski, 2004). A good working definition of knowledge is: “a fluid mix of framed experience, values, contextual information, and expert insight that provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information” (Davenport & Prusak, 2000). The goal of knowledge management is to capture knowledge

Figure 1. Portal technologies are necessary to maintain the competences that support sustained innovation

wherever it exists in an organization, and make it accessible to those who can derive value from it. Knowledge management tools help diffuse knowledge relatively quickly and cheaply to help connect related, but isolated, “pockets of innovation” (Tuomi, 2002).As illustrated by Santos, Doz, and Williamson (2004), companies can generate more innovations of higher value when they draw from a knowledge pool that is diverse both conceptually and geographically. A knowledge management capability also contributes to innovation by speeding the professional development of the knowledge worker (Carneiro, 2000). Empirical research shows that innovative companies usually have a strong knowledge management competence (McAdam, 2000).

Communication

A prerequisite to a competence in knowledge management is a competence in communication, which allows knowledge to be captured and used in different locations. A communication competence ensures that members of an organization can exchange plans and ideas and work in teams. A communication competence also promotes the development of social networks that span team and project boundaries, allowing individuals to seek the help and expertise they need to innovate, even if that expertise resides outside their local teams (Tsai & Goshal, 1998). Increasing the number and width of communication channels facilitates the transfer of information and knowledge essential to the innovation process (Hoegl, Parboteeah, & Munson, 2003).

Collaboration

Although new ideas or concepts often occur to individuals in isolation, the development of these ideas into innovative products, services, or processes that can create value for an organization almost always requires the work of a team of people. For innovation to take place, it is not enough that individuals communicate with one another. They also need to collaborate, that is, to share ideas, opinions, and hunches, and progressively and actively build upon each other’s understanding. In particular, they need to establish appropriate associations and teams in the context of the innovation task. Because a team’s creativity is greater than the sum of its individual members’ creativity (Pirola-Merlo & Mann, 2004), a competency in collaboration ensures that an organization can mine the full creative powers of its innovators. Hargadon (2003) found that innovation rarely involves the creation of completely new thoughts, processes, products, or services. Rather, innovative ideas stem from the recombination of ideas or components that are already in use. An organization can best support innovation by acting as a “broker” to connect, through collaborative networks, previously unrelated ideas, and combine and develop them into useful applications.

THE ROLE OF PORTALS

Creating an intranet portal is an effective strategy for improving an organization’s innovation competence by improving its competences in knowledge management, communication, and collaboration.

Knowledge Management

Portals can be used to provide a single point of access to knowledge that might reside in different departments and different locations. One type of portal, the “knowledge portal,” is an intranet Web site dedicated to the storage and reuse of explicit knowledge and the exchange of tacit knowledge (Kesner, 2003). The knowledge portal is an important element of the knowledge management toolset, and greatly enhances an organization’s knowledge management capability (Park & Kim, 2005). As such, it contributes to the innovation process in two ways:

1. by making it unnecessary for a knowledge creator and knowledge user to have a direct connection with one another, thereby closing the “structural holes” in innovation project exchange; and

2. by helping to create networks of practice, in which knowledge sharing becomes the norm (Van Baalen, Bloemhof-Ruwaard, & van Heck, 2005).

While portals help create a norm of information sharing, they unfortunately cannot solve the greatest challenge to knowledge management, the elicitation of tacit knowledge. No matter how willing an employee might be to explain certain instinctive knowledge, for example, why a particular molecule is likely to be an effective catalyst in a reaction, the employee might not be able to explain his or her insight. Furthermore, even in organizations where knowledge sharing is the norm, some employees will hide knowledge for their own benefit, despite the benefit they receive from what others share. If innovation leaders want their portals to support their innovation initiatives, they must also provide incentives for sharing knowledge, penalties for hoarding it, and procedures that simplify and encourage contributions to their portal’s knowledge repository.

Boeing-Rocketdyne employed a knowledge portal to help a virtual team develop a radically new product (Malhotra, Majchrzak, Carman, & Lott, 2001). The team was charged with designing a rocket engine that would reduce cost by a factor of 100, be brought to market 10-times faster than the company’s Space Shuttle main engine, and have a useful life three times as long. Practically none of the company’s employees thought it could be done. But with the help of a portal called “Notebook,” the team completed the project successfully in only 10 months, within budget, and with no team member spending more than 15% of their time on the project.

Communication

Portals can enhance a company’s communication competence by providing a technical environment and infrastructure for the exchange of information. In this context, they can serve as a unified, single point of access to various internal and external information resources that an innovator might need. They provide a kind of “home base” for communication that can be tailored in content and layout to both individual and organizational requirements. As employees gain confidence that they can rely on their company’s portal for information, it becomes an ideal way for managers to communicate with the people they manage. For example, human resource managers at Ernst & Young use the company’s portal, Community HomeSpace, to communicate HR policies, procedures, and guidance, and to distribute forms to employees (McDonald, 2005).

While company executives can use a portal for information dissemination, a portal’s primary value is to allow individuals to make their own decisions about what communications to receive and how to display them. For example, for an individual working on an innovation team, a portal could allow an individual to include on his or her opening portal page RSS feeds, such as those that report on relevant research, product introductions, or industry news. When authorized, an innovator might also include, on her opening portal page, alerts generated by collaboration software, such as Microsoft SharePoint, to remain informed of progress in projects relating to her own research, even though she is not on the project team.

Most corporate portals are not intended to share knowledge across company boundaries. The best ones, however, allow customers and suppliers to provide input into new product design and other innovation activities. Traditionally, companies hold on-site focus groups to obtain such feedback. However, portals create an opportunity to reduce the cost and time involved in obtaining the reaction and advice of partner firms. They even allow external parties to become full-time partners on innovation projects. With the universal availability of Web browsers, it has become relatively easy, despite security concerns, to allow external parties to access restricted areas of corporate portals. The problem is that these parties often fail to remember to regularly log into their partner’s portal site. Recent advances in portal-to-portal communication, especially the emergence of standards such as WSRP, allow external parties to include portlets, on their own portal pages that provide a constant communication pathway for work on joint innovation projects.

Despite a portal’s ability to present messages from and provide access to communication software tools, such as e-mail and instant messaging, at a single site, many users still prefer to access their communication software directly. This behavior mitigates the benefit of a portal as an innovation support tool.

Collaboration

Portals also help develop a collaboration competence. Portal technologies ease the management and control of a range of collaboration tools, such as e-mail, instant messaging, blogs, wikis, and discussion boards. Content management tools allow authorized users to update intranet and extranet portals with progress reports and links to innovation project documents. Project portals, portals available only to members of a project team, allow innovation team members to share designs, coordinate schedules, chat with one another online, and manage their projects. For example, employees at Perficient, an information technology consulting firm, use discussion forums at the company’s portal to collaborate on projects or discuss technical issues with their colleagues (IBM, 2005).

FUTURE TRENDS

Management gurus and futurists have proclaimed the advent of the “innovation economy” (Christensen, 2002; Davenport, Leibold, & Voelpel, 2006, for example), an economy that rewards the creation and development of new ideas. Even in today’s economy, innovation is a primary driver of firm growth and profitability (Cho & Pucik, 2005). As innovation leaders invest heavily in research and development, the need exists to improve the efficiency of the innovation process so as to increase the returns on investments in R&D. Portals can, and will likely be, one of the primary means of improving the return on R&D spending. Forrester Research (2005) predicts that companies’ portal usage will evolve from a current focus on application access and integration to one richly supporting innovation through collaborative processes and interaction.

In addition, software vendors are increasingly positioning their commercial collaboration products, such as IBM’s WebSphere Portal and Microsoft’s SharePoint, as knowledge portal platforms. Despite reports that some organizations have been disappointed by the return on their investments in knowledge portals because of a difficulty in keeping them current (Desouza & Yukika, 2005), many success stories exist (see, for example, Brewin & Tiboni, 2005; Teo, 2005). As portals’ communication and collaboration features improve, it is likely that knowledge portals will emerge as an important driver of R&D success and an enabler of the innovation process.

CONCLUSION

Portals support the innovation process by increasing firms’ competences in knowledge management, communication, and collaboration. They provide a platform that improves the ability of innovation team members to work effectively together and innovation leaders to learn from one another. As the world’s economy increasingly relies on innovation to drive growth, portal usage will evolve to focus on collaboration and the support of innovation.

KEY TERMS

Collaboration: The process by which many people work together to achieve a common goal.

Communication: The effective exchange of information.

Community of Practice (CoP): A group of people who share an interest, concern, problem, expertise, mandate, or sense of purpose.

Competence: A capability in a particular operational function or strategic direction that an organization achieves by combining the resources under its control.

Innovation: The creation, development, and implementation of new ideas, products, services, or processes.

Knowledge Management: Processes, usually supported by information technology, for capturing, organizing, storing, retrieving, and using the expertise, understanding, experience, and insight of an organization’s members.

Knowledge Portal: An intranet Web site dedicated to the storage and reuse of explicit knowledge and the exchange of tacit knowledge.

Resource-Based View of the Firm: A model of the firm, commonly seen in the literature on strategic management and organizational design, that views a firm as characterized by its unique resources, whose control, usage, and disposition by management help to determine its value.

Rich Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication (RSS): An XML protocol that provides a means to syndicate and aggregate Web content.

Web Services for Remote Portlets (WSRP): A standard that defines how to plug remote Web services into the pages of online portals.