The technology of building horizontal and vertical watermills entered Ireland from the Roman world, although the manner and exact date of transmission are unclear. Both forms, dating to around 630, are known from Little Island in Cork Harbor, while Cogitosus’s Life of Brigid (c. 650) describes a mill and gives an account of the cutting and fitting of a millstone. The horizontal watermill was the preferred form in early medieval Ireland, probably because it was better suited to small, fast-flowing steams and, also, because of the absence of gears, it was comparatively simple and cheap to build. Typically the horizontal mill was housed within a two-story, rectangular structure consisting of an upper and a lower room. The upper room contained the grinding stones and the hopper mechanism for the grain, while a vertical shaft connected the upper grinding stone with a horizontal water-wheel, composed of paddles, in the chamber below. Water was channeled by means of a millrace and a chute so that it fell onto the horizontal wheel causing it to turn. One revolution of the waterwheel produced one revolution of the upper rotary stone, which was usually no more than about three feet across.

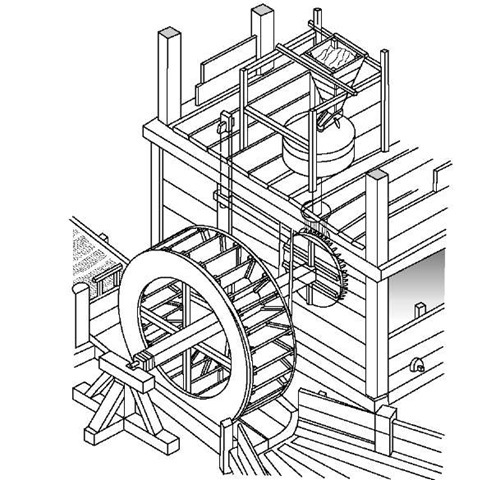

Vertical Watermill, circa 630 ce.

Vertical mills had an upright waterwheel with a horizontal axle that was geared to a vertical shaft, which was connected to the grinding stones. The gearing made it possible to adjust the rotation speed of the millstones, something that was impossible in the horizontal mill. Vertical waterwheels could be fed from above (overshot) or below (undershot) and both forms are evidenced in the Roman world. The fall of water from above gave the overshot mill greater power but it was more expensive and time-consuming to build. Accordingly, undershot mills are much more common. Apart from Little Island, another early example of a vertical undershot watermill, dating to about 710, is known from Morett, County Laois. Tide mills, in which a current was created by water descending from a pool where it had been trapped at high tide, are a feature of Atlantic Europe. The earliest Irish example is at Strangford Lough (619-621), while the Little Island mills, already mentioned, were also tidal. Early medieval mills are frequently found at ecclesiastical sites. Some have been found in isolation, but insufficient work has been done to determine whether they formed part of ecclesiastical and aristocratic estates or not. All of the known early examples are in rural locations but from the twelfth century onward, watermills are found in the Hiberno-Scandinavian port towns, where they tended to be located on feeder streams rather than tidal reaches.

Despite the ubiquity of watermills in early medieval Ireland, the grinding of grain by hand, using quern stones, remained commonplace. This changed after the Anglo-Norman invasion, when all grain had to be ground at designated mills. Such mills were a significant source of income for the ecclesiastical and territorial lords who monopolized the manufacture of flour until the close of the Middle Ages. A good example of a vertical undershot watermill of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century date was excavated at Patrick Street, Dublin. As is common with mills established at this time, the Patrick Street mill continued in use, periodically remodeled and rebuilt, into modern times.

Windmills are documented in Britain from 1137, but in Ireland they seem to be a feature of the thirteenth century. The earliest form was the post mill, a small wooden-framed building, which pivoted on a large upright beam (the post), and whose interior was accessed by means of a ladder. The entire building was turned so that the sails pointed into the wind. The structures were usually built on low mounds and survive today as circular earthworks with a distinctive internal cross pattern, which is all that survives of the foundations. There is a fine example at Shanid, County Limerick. The internal construction was much the same as that of watermills except that the vertical shaft fell downward to the stones. Tower windmills, consisting of a circular stone tower with a rotating cap that carried the sails, such as the example at Rindown, County Roscommon, are not evidenced in Ireland until the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Bridge mills were built at Dublin despite the obvious dangers that they posed in times of flooding. Although beer mills, fulling mills, and iron mills, which used pounders rather than rotary stones, are known from continental Europe by the eleventh century, there is little evidence for them in Ireland prior to the sixteenth century. Similarly, no evidence for boat mills is known.