To the extent that love is at the core of religion, it also inspires many forms of art. From temple altars where sacrifices were offered to please and appease the gods, to churches where the ultimate sacrifice of God himself is represented by the Crucifixion, images have been made to serve as messengers of devotion.

But there is about images, and especially religious images, a wish for them to materialize, to be, rather than merely represent what they portray: the beloved mother, child, martyr, father, gods and goddesses, prophets and saints. Consciously or not, willingly or not, devotion craves a tangible and corporeal subject. The problem is that a religious image is never more in jeopardy than when it succeeds in satisfying human appetites, since it then risks being associated with the worship, or love, of images—idolatry.

Idolatry may refer to worship of an image of a false god or gods—”false” being a euphuism for the wrong god or gods. Idolatry may refer to worshiping the image itself, as if the work of a human artist could be sacred. And when the work of art satisfies the worshiper’s deepest desire and appears miraculously, to come alive, weep, bleed, speak—the dangers of idolatry are manifest.

In the religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, idolatry is a sin, and the provocation for iconoclasm, literally “image breaking,” an act of violence, destruction, and hatred.

The demolition of works of art has an extensive history, one in which old chapters are continually revised and new chapters are added. Consider a 50-foot-high, 3,200-year-old statue of Ramses II, once thought to have been toppled by an earthquake. Today the statue is described as the victim of assault by Christian monks of the fifth century, who used hammers as part of their attack. In 2001, the Taliban used explosives to destroy two statues of Buddha in the Bamiyan Valley of Afghanistan, 140 miles northwest of Kabul. Known as the Bamiyan Buddhas, one of the two was 174 feet high, the tallest standing Buddha in the world; half a mile away was the second statue, 125 feet high. Their presence was first reported by a Chinese traveler, the monk Hiuan Tsang, who saw them in the year 632 CE. Tsang wrote that the tallest Buddha was “glittering with gold and precious ornaments.” What remained at the beginning of the second millennium was a damaged but awesome, towering statue, still amazing despite the destructive efforts of everyone from Genghis Khan and Tamerlane to a seventeenth-century Mogul artilleryman. Today there is just a great empty hole, like a high-rise shadow-box, in the face of the cliff.

The story of Moses and idolatry is among the most graphic and memorable descriptions of iconoclasm. While awaiting Moses’ descent from the summit of Mount Sinai, the Israelites, who had become fearful in his absence, turned to worshiping a golden calf. Although forewarned by God, Moses was so enraged by what he saw on his return that he shattered the tablets of the Decalogue—the covenant of his people with the Lord—and ground the graven image of the calf to dust. He forced the Israelites to swallow that dust, and even then had 3,000 of their number slain. Returning to the summit of the mountain, Moses brought back a new copy of the Decalogue, which, besides prohibiting the making and worshiping of idols, demanded that the Israelites love only one god and none other.

The example of Israelites worshiping a golden calf has stood for the sin of idolatry for over 2,000 years. It has also, perhaps ironically, been the subject of art. In his circa 1635 painting, in which he transformed the “calf” into a full-fledged bull, Nicolas Poussin chose to present the scene from the perspective of an audience, as if it were a stage play. Israelites dance in orgiastic frenzy in the foreground while Moses approaches, barely visible, in the left background. Aaron, dressed in white, gestures toward the bull with one hand and toward himself with the other. He seems to imply the connection of dissolution and self-indulgence with the worship of false gods.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf by Nicolas Poussin.

The distinction of works of art as objects of worship and for worship is sometimes clearer than others. The Torah (“teaching”), the foundation of Judaic thought, is written on a parchment scroll according to specific instructions, and is considered so sacred that the scroll itself may not be touched by a human hand when it is ceremonially read—instead a silver pointer is moved through the pages. Rolled up, the Torah is clothed in beautiful, decorated fabric, and kept in a protective enclosure—the Ark— where it may be symbolically protected by carved lions. These and other ornaments of the Torah, such as its shield and crown, as well as all objects fashioned for worship, are made as beautifully as possible to honor the sanctity of performing a mitzvah, a religious duty, or commandment of God.

The menorah is similarly used for performing a religious obligation. According to Judaic tradition, God gave Moses a detailed pattern for the menorah in Exodus 25:31, saying, “And thou shalt make a candlestick of pure gold.” A bas-relief sculpture on the Arch of Titus in Rome shows the Emperor Titus carrying off the menorah from the Temple in Jerusalem after the Roman conquest of Judea in 70 CE. Instances of looting objects of religious art, especially those as sacred and significant as the Temple menorah, compete with icono-clasm as a way of humiliating an enemy.

In 610 CE, Muhammad of Mecca began having visions in which the angel Gabriel appeared and dictated the text of the Qur’an to him. Under the influence of his revelations Muhammad believed that his mission was to reform tribal pagan religion and idolatry in the Arab world. In Mecca, Allah was the foremost of four deities worshiped at the Kaaba; Allah’s daughters were the others.

Muhammad’s battle on behalf of Allah’s singularity—especially his opposition to idolatry—created friction with Mecca’s merchant aristocracy, who profited from the tourists and pilgrims attracted to Mecca because of the Kaaba’s enticements. Consequently, Muhammad left Mecca for Medina in 622 CE.

By 630, having become an accomplished general as well as a powerful religious leader, Muhammad assembled an army of 10,000 men and marched back to Mecca. He destroyed the idols in and around the Kaaba, though he left its legendary Black Stone as a historic and sacred marker of the new faith.

After Muhammad’s death, Islam spread throughout Arabia, Persia, Egypt, Syria, and Palestine into Europe and North Africa, carrying with it the prohibition against idols and other religious imagery. Instead, devotion to Allah was expressed in spectacularly beautiful decorative, rather than representative, arts: floral, vegetal, and abstract designs. Just as the words of the Torah were sacred to Jews, so was transcription of the Qur’an holy to Muslims.

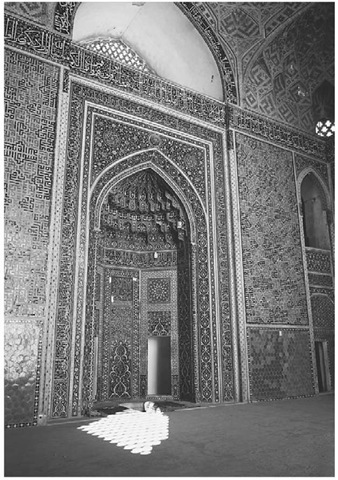

Arabic script and aniconic designs decorate mosques in every area where Islam settled, and they were stylistically linked to the traditions, skills, and materials of the regions and periods out of which they grew. For example, at the Madrasa Imami, a theological college in Isfahan, Persia (Iran), Qur’anic inscriptions in pure and beautiful calligraphy were accompanied by intricate geometric motifs as well as complex floral and vine-like patterns covering the walls of the mihrab, or prayer niche. The niche is now preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Relief sculpture on the Arch of Titus in Rome

Each carefully cut, glazed, painted tile has a rich cobalt blue underglaze. Persia was well known as a source of raw cobalt, which was widely traded throughout the region and into China. Persian architectural elements also traveled with the spread of Islam. Oriented toward Mecca, the niche contains a verse of the Qur’an for daily prayers and meditations.

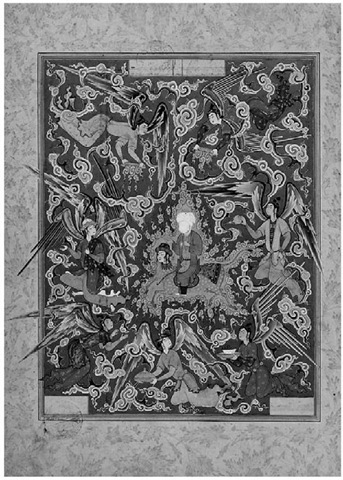

The topic arts, throughout the Islamic world, were dedicated largely to historic and romantic legends, but were occasionally emboldened with pictures of the Prophet Muhammad himself. In such cases his face was often left blank, or a white mask covered the bottom of it, in deference to religious proscriptions against representation. At times he was shown mounted on his steed, Baraq, who had a human head and transported the Prophet to heaven.

Christian imagery developed slowly, accumulating authority as the church itself grew from an illegal, hidden, secret cult to an immensely powerful one. Contributing to the influence of the church were rulers who associated themselves with and promoted Christianity. During the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries, the image of Jesus changed from a humble shepherd to a richly robed and commanding persona—a fitting companion for the emperors whose images were also portrayed in mosaics on the walls of churches.

Representations of the Crucifixion also reflect their historic context. The earliest known Crucifixion images, small oval seals, are from the middle of the fourth century. Even after the Emperor Constantine embraced Christianity and began building churches, and the new religion-seeking converts supported the use of images as a means of spreading its ideas, representation of the Crucifixion was still uncommon, and when portrayed, it was rudimentary and symbolic: Christ seemingly standing with his arms spread wide, his eyes open and his face expressionless. The Passion of Christ was not the kind of image to encourage conversion and did not become part of the iconography until Christianity was well established. The Gero Crucifix, a wooden sculpture about 6 feet high, installed at the Cologne Cathedral in 970 at the behest of Archbishop Gero, is a landmark: Christ is represented as gaunt and clearly in agony. This began an era when individuals contemplating the life of Christ felt a personal connection with him and his suffering. That closeness was intensified in the Gero sculpture by the fact that the head of Christ contains a receptacle designed to hold the host that, to the faithful, is literally the body of Christ.

In a famous letter he wrote in 600 CE, Pope Gregory I chastised a bishop for destroying images in his church. Gregory vigorously supported art as educational, especially for church-goers and potential churchgoers who could not read. In the eighth century, however, Emperor Leo III, believing that the use of images was a misplacement of love, began a campaign of iconoclasm. His motivation was also political. Leo was a ruler, not a cleric, and to him the church was gaining advantages in untaxed wealth, beautiful buildings, and devotional images that drew multitudes of faithful worshipers at the expense of imperial prosperity and power. In 726, Leo launched an iconoclastic rampage through the Byzantine world that lasted on and off for over 100 years.

Mihrab in the Masjid-e Jameh in Kerman.

The popes in Rome continued to approve the use of art in the church over the centuries. Their disagreement with Leo’s point of view contributed to a split between Eastern Orthodox and Western Roman Christianity that has never mended. Marilyn Stokstad describes the conflicting philosophies on which the opposing sides based their arguments for or against religious imagery.

Ascent of the Prophet Muhammad to Heaven, from a copy of the Falnama or topic of Omens.

The iconoclasts claimed that representations of Jesus Christ, because they portrayed him as human, promoted heresy by separating his divine from his human nature or by misrepresenting the two natures as one. Iconodules (defenders of devotional images) countered that, upon assuming human form as Jesus, God took on all human characteristics, including visibility. According to this view, images of Christ, testifying to that visibility, demonstrate faith in his dual nature and not, as the iconoclasts claimed, denial.

Few icons survived Leo’s campaign, but a revitalization of Byzantine art began during the ninth century and continued, interrupted by the Crusades, until Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE.

An icon is, by definition, a portrait of a holy person. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, icons of the Virgin and Child became influential in both the Eastern Orthodox and Roman churches. Their veneration was especially personal and devotional in the East. Though accustomed to seeing icons in museums, to understand their power is to imagine them in the churches for which they were made. In that context all of the worshiper’s senses are engaged: incense wafts by, candlelight flickers, the sounds of music and prayer are heard, and the taste of the Holy Communion persists, as the beholder is moved to touch and kiss the icon.

Byzantine art cast a wide spell that included Ethiopia, where icons of great beauty and sensibility were crafted. One such Ethiopian image is a panel of a diptych painted in the late fifteenth century. The anonymous artist was an outstanding painter in the court of an emperor who ruled from 1438 to 1468. On the other wing of the diptych are the half-portraits of a bevy of holy men and Saint George on his horse.

Ethiopians thought that they were meant to replace the Israelites as God’s chosen people, and that Jews in the entourage of Prince Me-nilek, son of King Solomon’s union with their own Queen of Sheba, had brought the Ark of the Covenant from Israel to Ethiopia. Conversion to Christianity began in 324 when Ezana, King of Aksum, accepted Jesus as the Jews’ promised Messiah.

Western scholars describe the fifteenth century as the golden age of Ethiopian art, and cite written evidence from the period to show that worshipers believed in miraculous images. This text describes a painting in which both Mary and Jesus are seen to move and, moreover, to speak directly to a monk in their presence. “The spirit of God dwells in it,” the text proclaims. “You should not think that it is a mere picture” (Haile 1992).The Virgin Mary on the wing of this diptych is a young Ethiopian beauty who radiates sweetness and whose voice, were she to speak, would chime like a musical whisper.

While Ethiopian art flourished, western Europe was in transition, with growing cities and an expanding middle class. It was a time of great changes—now known as the Renaissance —in both northern and Italian art. Wealthy merchants were joining rulers and the church as patrons of art. Humanism came increasingly to replace scholasticism, and artists, who began to stress and insist upon their own individuality, turned their attention from the ideal to the actual: mood, shadows, perspective, resemblance, emotion, movement, time, and distance.

During both the northern and Italian Renaissance, artists occasionally went so far as to show images of God. The most outstanding example is on Michelangelo’s ceiling of the Sistine Chapel: It represents the biblical origin of humankind, the moment when God created Adam.

In the sixteenth century, during the Protestant Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, the wealth, power, and corruption of the church again came under fierce attack, this time in western Europe. Once again religious images were destroyed, and those who defended them were assaulted, sometimes in spontaneous raids and sometimes in well-organized campaigns.

While it is difficult to understand how inanimate objects provoke reactions that range from passionate love to passionate hatred, it is well to remember that love, religion, and art, with their potential to unite and educate people, also have the power to tear them apart with envy, thievery, cruelty, violence, and with war and its henchman, iconoclasm.