ABOAB, ISAAC II

(1433-1493), rabbinical scholar. Known as the "last gaon of Castile," Aboab was a disciple of Isaac *Can-panton and head of the Toledo Yeshivah. Joseph *Caro refers to him as one of the greatest scholars of his time. During the final years before the expulsion from Spain he headed a yeshivah in Guadalajara, where, in 1491, Isaac *Abrabanel studied with him. When the edict of expulsion was issued against the Jews of Spain in 1492, Aboab and other prominent Jews went to Portugal to negotiate with King Joao ii regarding the admission of a number of Spanish exiles into his country. He and 30 other householders were authorized to settle in Oporto where he died seven months later; a eulogy was delivered by his pupil Abraham Zacuto. He had two sons: jacob, who ultimately settled in Constantinople where he published in 1538 his father’s Nehar Pishon, and abraham, one of the forced converts of 1497 who retained their Jewish loyalties in secret. Abraham adopted the name Duarte Dias, and many of his descendants returned to Judaism (see *Aboab Family). Isaac Aboab’s published works include the following: (1) a super-commentary on Nah manides’ commentary on the Pentateuch (Constantinople, 1525; Venice, 1548, etc.); (2) Nehar Pishon, homilies on the Pentateuch and other biblical books, edited by his son Jacob (Constantinople, 1538); (3) talmudic excursuses (Shitot) and novellae (those to Bezah were published in the responsa of Moses Galante (Venice, 1608) and Sefer Shitot ha-Kadmonim (1959); those to Bava Mezia are quoted by Bezalel Ashkenazi in his Shitah Mekubbezet); (4) responsa, appended to Sheva Einayim (Leghorn, 1745). Oxford and Cambridge manuscripts contain some of his novellae (on Ketubbot and Kiddushin), as well as homilies. A commentary on Jacob b. Asher’s Arbaah Turim, quoted and used by Joseph Caro and later authorities, and a commentary on Rashi (on the Pentateuch), as well as many responsa, are no longer extant.

ABOAB, ISAAC DE MATTATHIAS

(1631-1707), Dutch Sephardi scholar. His father Manuel Dias Henriques (1594-1667) was born in Oporto into a Marrano family, a descendant of Isaac *Aboab ii. After escaping from the Inquisition in Mexico he reverted to Judaism as Mattathias Aboab in Amsterdam in 1626. Isaac was a wealthy East India merchant trading with Spain and Portugal under the assumed name of Dennis Jennis. Although not a rabbi, as generally stated, he patronized rabbinical works and was a prolific writer and copyist. His only published work is a brief handbook of moral conduct, first written for his son in Hebrew but published in Portuguese under the title of Doutrina Particular (Amsterdam, 1687, 1691, reprinted by M.B. Amzalak, Lisbon, 1925). He advised his son to read Spanish books from time to time for his entertainment. He also wrote (1685) a morality play (Come-dia) on the life of Joseph, and compiled a history and genealogy of his own family.

ABOAB, JACOB BEN SAMUEL

(d. c. 1725), Venetian rabbi. He was the third son of Samuel Aboab, whom he succeeded as rabbi of Venice and whose biography he wrote (introduction to Samuel Aboab’s responsa Devar Shemuel (Venice, 1702)). He studied mathematics and astronomy and enjoyed a high repute for his extensive knowledge. Jacob’s halakhic decisions are included in contemporary works. He corresponded with Christian scholars on biographical and bibliographical topics relating to Jewish literature. Among his correspondents were Christian Theophil Unger, a Silesian pastor, and the Frankfurt scholar Ludolf Hiob. An index to Yakut Shimoni and a work on the ingredients of the incense of the sanctuary, both in manuscript, are ascribed to him. His responsum on the chanting of the Priestly Blessing is included in the collection Meziz u-Meliz (Venice, 1716), and a poem of his is appended to Kehunnat Avraham (Venice, 1719) by Abraham Cohen of Zante.

ABOAB, SAMUEL BEN ABRAHAM

(1610-1694), Italian rabbi. Aboab was born in Hamburg, but at the age of 13 he was sent by his father to study in Venice under David Franco, whose daughter he later married. After serving as rabbi in Verona, he was appointed in 1650 to Venice. At the age of 80 he had to leave Venice for some unknown cause and wandered from place to place, until the authorities permitted him to return shortly before his death. Aboab was renowned for both his talmudic and general knowledge and was consulted by the greatest of his contemporaries. He had many disciples. Modest, humble, and of a charitable nature, he devoted himself with particular devotion to communal matters. He was responsible for obtaining financial support from Western Europe for the communities in Erez Israel, and in 1643 collected funds for the ransoming of the Jews of Kremsier taken captive by the Swedes. Aboab was one of the most energetic opponents of the Shabbatean movement. At first he dealt with its followers with restraint, in the hope of avoiding a schism and the possible intervention of the secular authorities. Subsequently, however, he adopted a more rigorous attitude. When *Nathan of Gaza reached Venice in 1668, Samuel was among the rabbis of Venice who interrogated him on his beliefs and activities. His published works include Devar Shemuel, responsa (Venice, 1702) published by his son Jacob. It is prefaced by a biography and his ethical will to his sons,Sefer ha-Zikhronot (Prague, between 1631 and 1651), contains ten principles on the fulfillment of the commandments. Two more of his works, Mazkeret ha-Gittin and Tikkun Soferim, exist in manuscript. Some of his letters were published by M. Benayahu (see bibliography). Two of his sons, Abraham and Jacob, succeeded him after his death. His other two sons were Joseph and david. Joseph had acted as his deputy during his wanderings; eventually he settled in Erez Israel. He wrote halakhic rulings on *Jacob b. Asher’s Arbaah Turim and died in Hebron.

ABOAB DA FONSECA, ISAAC

(1605-1693), Dutch Sephardi rabbi. Aboab was born in Castro Daire, Portugal, of a Marrano family, as Simao da Fonseca, son of Alvaro da Fon-seca alias David Aboab. He was brought as a child to St. Jean de Luz in France and then to Amsterdam, where he was given a Jewish upbringing; he was considered the outstanding pupil of R. Isaac *Uzziel. At the age of 21, Aboab was appointed hakham of the congregation Bet Israel. After the three Sephardi congregations in Amsterdam amalgamated in 1639, he was retained by the united community as senior assistant to R. Saul Levi *Morteira. In 1641, following the Dutch conquests in *Brazil, Aboab joined the Amsterdam Jews who established a community at *Recife (Pernambuco) as their hakham, thus becoming the first American rabbi. He continued for 13 years as the spiritual mainstay of the community. After the repulse of the Portuguese attack on the city in 1646, Aboab composed a thanksgiving narrative hymn describing the past sufferings, Zekher Asiti le-Niflaot El ("I made record of the mighty deeds of God"), the first known Hebrew composition in the New World that has been preserved. He also wrote here his Hebrew grammar, Melekhet ha-Dikduk, still unpublished, and a treatise on the Thirteen Articles of Faith, now untraceable. After the Portuguese victory in 1654, Aboab and other Jews returned to Amsterdam. Morteira having recently died, Aboab was appointed hakham as well as teacher in the talmud torah, principal of the yeshivah, and member of the bet din; in this capacity he was one of the signatories of the ban of excommunication issued against *Spinoza in 1656. Aboab became celebrated as a preacher, and some of his sermons and eulogies have been published. The Jesuit Antonio de Vieira, comparing him with his contemporary *Manasseh b. Israel, observed that Aboab knew what he said whereas the other said what he knew. It was a pulpit address delivered by Aboab in 1671 which prompted the construction of the magnificent synagogue of the Sephardi community in Amsterdam; he preached the first sermon in the new building on its dedication four years later. Along with most of the Amsterdam community, Aboab was an ardent supporter of *Shabbetai Z evi, and was one of the signatories of a letter of allegiance addressed to him in 1666; he also published Viddui ("Confession of Sins," Amsterdam, 1666). Aboab translated from Spanish into Hebrew the works of the kabbalist Abraham Cohen de *Herrera, BeitElohim and Shaar ha-Shamayim (Amsterdam, 1655). His novellae on tractate Kiddushin and a work on reward and punishment entitled Nishmat Hayyim have not been published. His most ambitious production was a rendering of the Pentateuch in Spanish together with a commentary (Parafrasis Commentada sobre el Pentateucho, Amsterdam, 1688). Aboab died at the age of 88 on April 4, 1693. The bereavement of their spiritual guide was so keenly felt by Amsterdam Jewry that for many years the name of Aboab and the date of his death were incorporated in the engraved border of all marriage contracts issued by the community. The breadth of Aboab’s interests in non-Hebrew as well as Hebrew literature is illustrated in the sale catalogue of his library which appeared shortly after his death, one of the earliest known in Hebrew bibliography.

ABOMINATION

Three Hebrew words connote abomination: nayin (toevah), (shekez, sheqez) or flpttf (shikkuz, shiqquz), and VlitS (piggul); to’evah is the most important of this group. It appears in the Bible 116 times as a noun and 23 times as a verb and has a wide variety of applications, ranging from food prohibitions (Deut. 14:3), idolatrous practices (Deut. 12:31; 13:15), and magic (Deut. 18:12) to sex offenses (Lev. 18:22ff.) and ethical wrongs (Deut. 25:14-16; Prov. 6:16-19). Common to all these usages is the notion of irregularity, that which offends the accepted order, ritual, or moral. It is incorrect to arrange the toevah passages according to an evolutionary scheme and thereby hope to demonstrate that the term took on ethical connotations only in post-Exilic times. For in Proverbs, where the setting is exclusively ethical and universal but never ritual or national, toevah occurs mainly in the oldest, i.e., pre-Exilic.Moreover, Ezekiel, who has no peer in ferreting out cultic sins, uses to’evah as a generic term for all aberrations detestable to God, including purely ethical offenses (e.g., 18:12, 13, 24). Indeed, there is evidence that to’evah originated not in the cult, and certainly not in prophecy, but in wisdom literature. This is shown not only by its clustering in the oldest levels of Proverbs but also in its earliest biblical occurrence where the expression to’avat Mizrayim (Gen. 43:32; 46:34; Ex. 8:22, ascribed to the j source) refers to specific contraventions of ancient Egyptian norms. Furthermore, Egyptian has a precise equivalent to toevah, and it occurs in similar contexts, e.g., "Thus arose the abomination of the swine for Horus’ sake" (for a Canaan-ite-Phoenician parallel, note tbtcstrt – Tabnit of Sidon (third century B.c.E.) – in Pritchard, Texts, 505). Thus the sapiential background of the term in the ancient Near East is fully attested. True, toevah predominates in Deuteronomy (16 times) and Ezekiel (43 times), but both books are known to have borrowed terms from wisdom literature (cf. Deut. 25:13 ff., and Prov. 11:1; 20:23) and transformed them to their ideological needs. The noun sheqez is found in only four passages where it refers to tabooed animal flesh (e.g., Lev. 11:10-43). However, the verb fp^, found seven times, is strictly a synonym of a^n (e.g., Deut. 7:26; the noun may also have had a similar range). Shiqquz, on the other hand, bears a very specific meaning: in each of its 28 occurrences it refers to illicit cult objects. Piggul is an even more precise, technical term denoting sacrificial flesh not eaten in the allotted time (Lev. 7:18; 19:7); though in nonlegal passages it seems to have a wider sense (Ezek. 4:14; cf. Isa. 65:4). According to the rabbis (Sifra 7:18, etc.) the flesh of a sacrifice was considered a piggul if the sacrificer, at the time of the sacrifice, had the intention of eating the flesh at a time later than the allotted time. Under these circumstances, the sacrifice was not considered accepted by God and even if the sacrificer ate of it in the alloted time he was still liable to the punishment of *karet, i.e., the flesh was considered piggul by virtue of the intention of the sacrificer. This is an extension of the biblical text according to which he would be liable for punishment only if he ate it at the inappropriate time. The rabbis based their interpretation on the biblical passage "It shall not be acceptable" (Lev. 7:18). They reasoned: How could the Lord having already accepted the sacrifice then take back His acceptance after it was later eaten at the wrong time.

ABOMINATION OF DESOLATION

Literal translation of the Greek BSeAu-y|ia epr||ir|^CTEW? (1 Macc. 1:54). This in turn, evidently goes back to a Hebrew or Aramaic expression similar to shiqquz shomen ("desolate," i.e., horrified – for "horrifying" – "abomination"; Dan. 12:11). Similar, but grammatically difficult, are ha-shiqquz meshomem, "a horrifying abomination," (disregard the Hebrew definite article?; ibid. 11:31); shiqquzim meshomem, "a horrifying abomination", disregarding the ending of the noun? (ibid. 9:27); and ha-peshac shomem, "the horrifying offense" (ibid. 8:13). According to the Maccabees passage, it was something which was constructed (a form of the verb oiKoSo|ie«) on the altar (of the Jerusalem sanctuary), at the command of *Antiochus iv Epiphanes, on the 15th day of Kislev (i.e., some time in December) of the year 167 B.c.E.; according to the Daniel passages, it was something that was set (a form of ntn) there. It was therefore evidently a divine symbol of some sort (a statue or betyl [sacred stone]), and its designation in Daniel and Maccabees would then seem to be a deliberate cacophemism for its official designation. According to ii Maccabees 6:2, Antiochus ordered that the Temple at Jerusalem be renamed for Zeus Olympios – "Olympian Zeus." Since Olympus, the abode of the gods, is equated with heaven, and Zeus with the Syrian god "Lord of Heaven" – Phoenician Bcal Shamem, Aramaic Be’el Shemain (see Bickerman) – it was actually Baal Shamem, "the Lord of Heaven," who was worshiped at the Jerusalem sanctuary during the persecution; and of this name, Shomem, best rendered "Horrifying Abomination," is a cacophemistic distortion.

ABONY

Town in Pest-Pilis-Solt-Kiskun county, Hungary, located southeast of Budapest. One Jew settled there in 1745; the census of 1767 mentions eight Jews. The Jewish population ranged from 233 in 1784 to 431 in 1930, reaching a peak of 912 in 1840. The Jewish community was organized in 1771 concurrently with the organization of a Chevra Kadisha. The community’s first synagogue was built in 1775. The members of the community consisted of merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, peddlers and, starting in 1820, tenant farmers. From 1850 onward Jews were able to own land. A magnificent new synagogue was built in 1825 that was mentioned in a responsum by Moses *Sofer. A Jewish teacher was engaged for the community in 1788, and a Jewish school was opened in 1766 and moved to a separate building in 1855. In 1869 a Neolog community was established in town. It was in Abony that the Austro-Hungarian kolel of Jerusalem was established in 1863. Among the rabbis of Abony were Jacob Herczog (1837-57), author of Pert Ya’akov (1830); Isaac (Ignac) *Kunstadt (1862-82), author of Luah Eretz, 1-2 (1886-87); Bela Vajda (1889-1901), author of a history of the local Jewish community; and Naphtali Blumgr-und (1901-18). In April 1944, the Neolog community of 275 was led by Izsak Vadasz.

According to the census of 1941, Abony had 315 Jewish inhabitants and 16 converts identified as Jews under the racial laws. Early in May 1944, the Jews were placed in a ghetto which also included the Jews from the following neighboring villages in Abony district: Jaszkarajeno, Kocser, Toszeg, Tor-tel, Ujszasz, and Zagyvarekas. After a few days, the Jews were transferred to the ghetto of Kecskemet, from where they were deported to Auschwitz in two transports on June 27 and 29. In 1946, Abony had a Jewish population of 56. Most of them left after the Communists took over in 1948 and especially after the Revolution of 1956. By 1959, their number was reduced to 19, and a few years later the community ceased to exist. The synagogue is preserved as a historic monument.

ABORTION

Abortion is defined as the artificial termination of a woman’s pregnancy.

In the Biblical Period

A monetary penalty was imposed for causing abortion of a woman’s fetus in the course of a quarrel, and the penalty of death if the woman’s own death resulted therefrom. "And if men strive together, and hurt a woman with child, so that her fruit depart, and yet no harm follow – he shall be surely fined, according as the woman’s husband shall lay upon him; and he shall pay as the judges determine. But if any harm follow – then thou shall give life for life" (Ex. 21:22-23). According to the Septuagint the term "harm" applied to the fetus and not to the woman, and a distinction is drawn between the abortion of a fetus which has not yet assumed complete shape -for which there is the monetary penalty – and the abortion of a fetus which has assumed complete shape – for which the penalty is "life for life." Philo (Spec., 3:108) specifically prescribes the imposition of the death penalty for causing an abortion, and the text is likewise construed in the Samaritan Targum and by a substantial number of Karaite commentators. A. *Geiger deduces from this the existence of an ancient law according to which (contrary to talmudic halakhah) the penalty for aborting a fetus of completed shape was death (Ha-Mikra ve-Targumav, 280-1, 343-4). The talmudic scholars, however, maintained that the word "harm" refers to the woman and not to the fetus, since the scriptural injunction, "He that smiteth a man so that he dieth, shall surely be put to death" (Ex. 21:12), did not apply to the killing of a fetus (Mekh. SbY, ed. Epstein-Melamed, 126; also Mekh. Mishpatim 8; Targ. Yer., Ex. 21:22-23; bk 42a). Similarly, Josephus states that a person who causes the abortion of a woman’s fetus as a result of kicking her shall pay a fine for "diminishing the population," in addition to paying monetary compensation to the husband, and that such a person shall be put to death if the woman dies of the blow (Ant., 4:278). According to the laws of the ancient East (Sumer, Assyria, the Hittites), punishment for inflicting an aborting blow was monetary and sometimes even flagellation, but not death (except for one provision in Assyrian law concerning willful abortion, self-inflicted). In the Code of *Hammurapi (no. 209, 210) there is a parallel to the construction of the two quoted passages: "If a man strikes a woman [with child] causing her fruit to depart, he shall pay ten shekalim for her loss of child. If the woman should die, he who struck the blow shall be put to death."

In the Talmudic Period

In talmudic times, as in ancient *halakhah, abortion was not considered a transgression unless the fetus was viable (ben keyama; Mekh. Mishpatim 4 and see Sanh. 84b and Nid. 44b; see Rashi; ad loc.), hence, even if an infant is only one day old, his killer is guilty of murder (Nid. 5:3). In the view of R. Ishmael, only a *Gentile, to whom some of the basic transgressions applied with greater stringency, incurred the death penalty for causing the loss of the fetus (Sanh. 57b). Thus abortion, although prohibited, does not constitute murder (Tos., Sanh. 59a; Hul. 33a). The scholars deduced the prohibition against abortion by an a fortiori argument from the laws concerning abstention from procreation, or onanism, or having sexual relations with one’s wife when likely to harm the fetus in her womb – the perpetrator whereof being regarded as "a shedder of blood" (Yev. 62b; Nid. 13a and 31a; Havvat Ya’ir, no. 31; Sheelat Yavez, 1:43; Mishpetei Uziel, 3:46). This is apparently also the meaning of Josephus’ statement that "the Law has commanded to raise all the children and prohibited women from aborting or destroying seed; a woman who does so shall be judged a murderess of children for she has caused a soul to be lost and the family of man to be diminished" (Apion, 2:202).

The Zohar explains that the basis of the prohibition against abortion is that "a person who kills the fetus in his wife’s womb desecrates that which was built by the Holy One and His craftsmanship." Israel is praised because notwithstanding the decree, in Egypt, "every son that is born ye shall cast into the river" (Ex. 1:22), "there was found no single person to kill the fetus in the womb of the woman, much less after its birth. By virtue of this Israel went out of bondage" (Zohar, Ex., ed. Warsaw, 3b).

Abortion is permitted if the fetus endangers the mother’s life. Thus, "if a woman travails to give birth [and it is feared she may die], one may sever the fetus from her womb and extract it, member by member, for her life takes precedence over his" (Oho. 7:6). This is the case only as long as the fetus has not emerged into the world, when it is not a life at all and "it may be killed and the mother saved" (Rashi and Meiri, Sanh. 72b). But, from the moment that the greater part of the fetus has emerged into the world – either its head only, or its greater part – it may not be touched, even if it endangers the mother’s life: "ein dohin nefesh mi-penei nefesh" ("one may not reject one life to save another" – Oho. and Sanh. ibid.). Even though one is enjoined to save a person who is being pursued, if necessary by killing the pursuer (see *Penal Law), the law distinguishes between a fetus which has emerged into the world and a "pursuer," since "she [the mother] is pursued from heaven" (Sanh. 72b) and moreover, "such is the way of the world" (Maim., Yad, Roze’ah 1:9) and "one does not know whether the fetus is pursuing the mother, or the mother the fetus" (tj Sanh. 8:9, 26c). However, when the mother’s life is endangered, she herself may destroy the fetus – even if its greater part has emerged – "for even if in the eyes of others the law of a fetus is not as the law of a pursuer, the mother may yet regard the fetus as pursuing her" (Meiri, ibid.).

Contrary to the rule that a person is always fully liable for damage (muad le-olam), whether inadvertently or willfully caused (bk 2:6, see *Penal Law, Torts), it was determined with regard to damage caused by abortion, that "he who with the leave of the bet din and does injury – is absolved if he does so inadvertently, but is liable if he does so willfully – this being for the good order of the world" (Tosef., Git. 4:7), for "if we do not absolve those who have acted inadvertently, they will refrain from carrying out the abortion and saving the mother" (Tashbez, pt. 3, no. 82; Minhat Bik., Tosef., Git. 4:7).

In the Codes

Some authorities permit abortion only when there is danger to the life of the mother deriving from the fetus "because it is pursuing to kill her" (Maim. loc. cit.; Sh. Ar., hm 425:2), but permission to "abort the fetus which has not emerged into the world should not be facilitated [in order] to save [the mother] from illness deriving from an inflammation not connected with the pregnancy, or a poisonous fever … in these cases the fetus is not [per se] the cause of her illness" (Pahad Yizhak, s.v. Nefalim). Contrary to these opinions, the majority of the later authorities (aharonim) maintain that abortion should be permitted if it is necessary for the recuperation of the mother, even if there is no mortal danger attaching to the pregnancy and even if the mother’s illness has not been directly caused by the fetus (Maharit, Resp. no. 99). Jacob *Emden permitted abortion "as long as the fetus has not emerged from the womb, even if not in order to save the mother’s life, but only to save her from the harassment and great pain which the fetus causes her" (She’elat Yavez, 1:43). A similar view was adopted by Benzion Meir Hai *Ouziel, namely that abortion is prohibited if merely intended for its own sake, but permitted "if intended to serve the mother’s needs … even if not vital"; and who accordingly decided that abortion was permissible to save the mother from the deafness which would result, according to medical opinion, from her continued pregnancy (Mishpetei Uziel, loc. cit.). In the Kovno ghetto, at the time of the Holocaust, the Germans decreed that every Jewish woman falling pregnant shall be killed together with her fetus. As a result, in 1942 Rabbi Ephraim Oshry decided that an abortion was permissible in order to save a pregnant woman from the consequences of the decree (Mi-Maamakim, no. 20).

The permissibility of abortion has also been discussed in relation to a pregnancy resulting from a prohibited (i.e., adulterous) union (see Havvat Ya’ir, ibid.). Jacob Emden permitted abortion to a married woman made pregnant through her adultery, since the offspring would be a mamzer (see *Mamzer), but not to an unmarried woman who becomes pregnant, since the taint of bastardy does not attach to her offspring (She’elat Yavez, loc. cit., s.v. Yuhasin). In a later respon-sum it was decided that abortion was prohibited even in the former case (Lehem ha-Panim, last Kunteres, no. 19), but this decision was reversed by Ouziel, in deciding that in the case of bastardous offspring abortion was permissible at the hands of the mother herself (Mishpetei Uziel, 3, no. 47).

In recent years the question of the permissibility of an abortion has also been raised in cases where there is the fear that birth may be given to a child suffering from a mental or physical defect because of an illness, such as rubeola or measles, contracted by the mother or due to the aftereffects of drugs, such as thalidomide, taken by her. The general tendency is to uphold the prohibition against abortion in such cases, unless justified in the interests of the mother’s health, which factor has, however, been deemed to extend to profound emotional or mental disturbance (see: Unterman, Zweig, in bibliography). An important factor in deciding whether or not an abortion should be permitted is the stage of the pregnancy: the shorter this period, the stronger are the considerations in favor of permitting abortion (Havvat Ya’ir and She’elat Yavez, loc. cit.; Beit Shelomo, hm 132).

Contemporary Authorities

Contemporary halakhic authorities adopted a strict approach towards the problem of abortion. R. Isser Yehuda *Unterman defined the abortion of a fetus as "tantamount to murder," subject to a biblical prohibition. R. Moses *Feinstein adopted a particularly strict approach. In his view, abortion would only be permitted if the doctors determined that there was a high probability that the mother would die were the pregnancy to be continued. Where the mother’s life is not endangered, but the abortion is required for reasons of her health, or where the fetus suffers from Tay-Sachs disease, or Down’s syndrome, abortion is prohibited, the prohibition being equal in severity to the prohibition of homicide. This is the case even if bringing the child into the world will cause intense suffering and distress, to both the newborn and his parents. According to R. Feinstein, the prohibition on abortion also applies where the pregnancy was the result of forbidden sexual relations, which would result in the birth of a mamzer.

Other halakhic authorities - foremost among them R. Eliezer *Waldenberg – continued the line of the accepted halakhic position whereby the killing of a fetus did not constitute homicide, being a prohibition by virtue of the reasons mentioned above. Moreover, according to the majority of authorities, the prohibition was of rabbinic origin. In the case of a fetus suffering from Tay-Sachs disease R. Waldenberg ruled: "it is permissible … to perform an abortion, even until the seventh month of her pregnancy, immediately upon its becoming absolutely clear that such a child will be born thus." In his ruling he relies inter alia on the responsa of Maharit (R. Joseph *Trani) and She’elat Yavez (R. Jacob *Emden), who permit abortion "even if not in order to save the mother’s life, but only to save her from the harassment and the great pain that the fetus causes her" (see above). R. Waldenberg adds: "… Consequently, if there is a case in which the halakhah would permit abortion for a great need and in order to alleviate pain and distress, this would appear to be a classic one. Whether the suffering is physical or mental is irrelevant, since in many instances mental suffering is greater and more painful than physical distress" (Ziz Eliezer, 13:102). He also permitted the abortion of a fetus suffering from Down’s syndrome. Quite frequently, however, the condition of such a child is far better than that of the child suffering from Tay-Sachs, both in terms of his chances of survival and in terms of his physical and mental condition. Accordingly, "From this [i.e., the general license in the case of Tay-Sachs disease] one cannot establish an explicit and general license to conduct an abortion upon discovering a case of Down’s syndrome … until the facts pertaining to the results of the examination are known, and the rabbi deciding the case has thoroughly examined the mental condition of the couple" (ibid., 14:101).

In the dispute between Rabbis Feinstein and Walden-berg relating to Maharit’s responsum, which contradicts his own conclusion, R. Feinstein writes: "This responsum is to be ignored … for it is undoubtedly a forgery compiled by an errant disciple and ascribed to him" (p. 466); and regarding the responsum of R. Jacob Emden, which also contradicts his own conclusion, he claims that "… the argument lacks any cogency, even if it was written by as great a person as the Ya’vez’ (p. 468). In concluding his responsum, R. Feinstein writes of "the need to rule strictly in light of the great laxity [in these matters] in the world and in Israel." Indeed, this position is both acceptable and common in the halakhah, but in similar cases the tendency has not been to reject the views of earlier authorities, or to rule that they were forged, but rather to rule stringently, beyond the letter of the law, due to the needs of the hour (see Waldenberg, ibid., 14:6).

In the State of Israel

Abortion and attempted abortion were prohibited in the Criminal Law Ordinance of 1936 (based on English law), on pain of imprisonment (sec. 175). An amendment in 1966 to the above ordinance relieved the mother of criminal responsibility for a self-inflicted abortion, formerly also punishable (sec. 176). In this context, causing the death of a person in an attempt to perform an illegal abortion constituted manslaughter, for which the maximum penalty is life imprisonment. An abortion performed in good faith and in order to save the mother’s life, or to prevent her suffering serious physical or mental injury, was not a punishable offense. Terms such as "en-dangerment of life" and "grievous harm or injury" were given a wide and liberal interpretation, even by the prosecution in considering whether or not to put offenders on trial.

The Penal Law Amendment (Termination of Pregnancy) 5737-1977 provided, inter alia, that "a gynecologist shall not bear criminal responsibility for interrupting a woman’s pregnancy if the abortion was performed at a recognized medical institution and if, after having obtained the woman’s informed consent, advance approval was given by a committee consisting of three members, two of whom are doctors (one of them an expert in gynecology), and the third a social worker." The law enumerates five cases in which the committee is permitted to approve an abortion: (1) the woman is under legally marriageable age (17 years old) or over 40; (2) the pregnancy is the result of prohibited relations or relations outside the framework of marriage; (3) the child is likely to have a physical or a mental defect; (4) continuance of the pregnancy is likely to endanger the woman’s life or cause her physical or mental harm; (5) continuance of the pregnancy is likely to cause grave harm to the woman or her children owing to difficult family or social circumstances in which she finds herself and which prevail in her environment (§316). The fifth consideration was the subject of sharp controversy and was rejected inter alia by religious circles. They claimed that the cases in which abortion is halakhically permitted – even according to the most lenient authorities – are all included in the first four reasons. In the Penal Law Amendment adopted by the Knesset in December 1979, the fifth reason was revoked.

The Israeli Supreme Court has also dealt with the question of the husband’s legal standing in an application for an abortion filed by his wife; that is, is the committee obliged to allow the husband to present his position regarding his wife’s application? The opinions in the judgment were divided. The majority view (Justices Shamgar, Ben-Ito) was that the committee is under no obligation to hear the husband, although it is permitted to do so. According to the minority view (Justice Elon), the husband has the right to present his claims to the committee (other than in exceptional cases, e.g., where the husband is intoxicated and unable to participate in a balanced and intelligent consultation, or where the urgency of the matter precludes summoning the husband). According to this view, the husband’s right to be heard by the committee is based on the rules of natural justice, that find expression in the rabbinic dictum: "There are three partners in a person: The Holy One blessed be He, his father and his mother" (Kid. 30b; Nid. 31a; c.A. 413/80 Anon. v. Anon., p.d. 35 [3] 57). Elon further added (p. 89): "It is well known that in Jewish law no ‘material’ right of any kind was ever conferred upon the parents, even with respect to their own child who had already been born. The parents relation to their natural offspring is akin to a natural bond, and in describing this relationship, notions of legal ownership are both inadequate and offensive" (c.A. 488/97 Anon. et al. v. Attorney General, 32 (3), p. 429-30). This partnership is based on the deep and natural involvement of the parents in the fate of the fetus who is the fruit of their loins, and exists even where the parents are not married, and a fortiori is present when the parents are a married couple building their home and family. When the question of termination of a pregnancy arises, each of the two parents has a basic right – grounded in natural and elementary justice – to be heard and to express his or her feelings, prior to the adoption of any decision regarding the termination of the pregnancy and the destruction of the fetus.

ABRABANEL

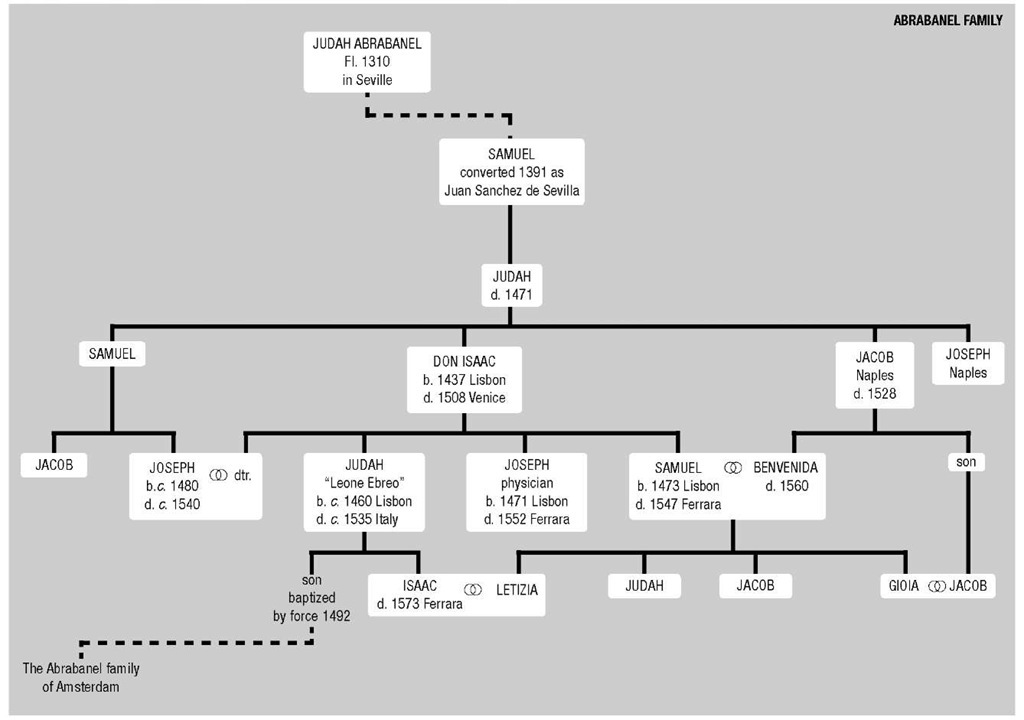

Family in Italy. After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, the three brothers, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph, founders of the Italian family, settled in the kingdom of Naples. The family tree shows the relationships of the Italian Abrabanels. Because of their considerable wealth and capabilities the Abrabanel brothers reached a position of some power both in relation to the Naples authorities and their coreligionists. isaac was a financier, philosopher, and exe-gete; jacob led the Jewish community in Naples; and Joseph dealt in grain and foodstuffs. All three were included among the 200 families exempted by the Spaniards when they expelled the Jews from the kingdom of Naples in 1511. Isaac had three sons, judah (better known as the philosopher Leone Ebreo); Joseph, a noted physician who lived first in southern Italy where he treated the famous Spanish general Gonsalvo de Cordoba, then moved to Venice, and later to Ferrara where he died; and samuel, who married his cousin benvenida (See *Abrabanel, Benvenida), a woman of such talent that the Spanish viceroy in Naples, Don Pedro of Toledo, is said to have chosen her to teach his daughter Eleonora. Samuel, who commanded a capital of about 200,000 ducats, was such an able financier that Don Pedro used to seek his advice. When his father-in-law Jacob died, Samuel succeeded him as leader of the Naples community. In 1533, when Don Pedro issued a new edict expelling the Neapolitan Jews, Samuel managed to have the order suspended. However, his efforts were unavailing when the viceroy renewed the edict in 1540, and in the next year all the remaining Jews were compelled to leave the kingdom of Naples. Samuel now moved to Ferrara where he enjoyed the favor of the duke until his death. Benvenida continued her husband’s loan-banking business with the support of her pupil Eleonora, now duchess of Tuscany, and extended it to Tuscany. To lighten her burden she took her sons jacob and judah and isaac, Samuel’s natural son, into the management of the widespread business. Three years after Samuel’s death in 1547, a struggle broke out over the inheritance among the three sons: Jacob and Judah (the recognized sons of Samuel and Benvenida) on the one hand and Isaac (the natural son) on the other. The struggle, which dealt with the legal validity of Samuel’s will, involved some of the period’s most famous rabbis: R. Meir b. Isaac Katzenellenbogen (Maharam), R. Jacob b. Azriel Diena of Reggio, R. Jacob Israel b. Finzi of Recanati, R. Samuel de Medina, R. Joseph b. David Ibn Lev, and R. Samuel b. Moses Kalai. The conflict was settled apparently by Maharam’s arbitration in 1551. One of Benvenida’s sons-in-law who became a partner in her business was jacob, later private banker of Cosimo de’ Medici, and his financial representative at Ferrara. Following Jacob’s advice, Duke Cosimo invited Jews from the Levant to settle in Tuscany in 1551 to promote trade with the Near East, granting them favorable conditions. Members of the family living in Italy, especially Venice, after this period, Abraham (d. 1618), Joseph (d. 1603), and Veleida (d. 1616), were presumably descended from the Ferrara branch.

ABRABANEL, ABRAVANEL

(Heb.![]() inaccurately Abarbanel; before 1492 also Abravaniel and Brabanel), Sephardi family name. The name is apparently a diminutive of Abravan, a form of Abraham not unusual in Spain, where the "h" sound was commonly rendered by "f" or "v." The family, first mentioned about 1300, attained distinction in Spain in the 15th century. After 1492, Spanish exiles brought the name to Italy, North Africa, and Turkey. Members of the family who were baptized in Portugal at the time of the Forced Conversion of 1497 preserved the name in secret and revived it in the 17th century in the Sephardi communities of Amsterdam, London, and the New World. The family was also found in Poland and southern Russia. Of recent years Sephardi immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean area have reintroduced it into western countries. It is also common in Israel.

inaccurately Abarbanel; before 1492 also Abravaniel and Brabanel), Sephardi family name. The name is apparently a diminutive of Abravan, a form of Abraham not unusual in Spain, where the "h" sound was commonly rendered by "f" or "v." The family, first mentioned about 1300, attained distinction in Spain in the 15th century. After 1492, Spanish exiles brought the name to Italy, North Africa, and Turkey. Members of the family who were baptized in Portugal at the time of the Forced Conversion of 1497 preserved the name in secret and revived it in the 17th century in the Sephardi communities of Amsterdam, London, and the New World. The family was also found in Poland and southern Russia. Of recent years Sephardi immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean area have reintroduced it into western countries. It is also common in Israel.

The first of the family who rose to eminence was judah abrabanel of Cordoba (later of Seville), treasurer and tax-collector under Sancho iv (1284-95) and Ferdinand iv (1295-1312). In 1310 he and other Jews guaranteed the loans made to the crown of Castile to finance the siege of Algeci-ras. It is probable that he was almoxarife ("collector of revenues") of Castile. Another eminent member of the family was samuel of Seville, of whom Menahem b. Zerah wrote that he was "intelligent, loved wise men, befriended them, was good to them and was eager to study whenever the stress of time permitted." He had great influence at the court of Castile. In 1388 he served as royal treasurer in Andalusia. During the anti-Jewish riots of 1391 he was converted to Christianity under the name of Juan Sanchez (de Sevilla) and was appointed comptroller in Castile. It is thought that a passage in a poem in the Cancionero de Baena, attributed to Alfonso Alvarez de Villasandino, refers to him. He and his family apparently later fled to Portugal, where they reverted to Judaism and filled important governmental posts. His son, judah (d. 1471), was in the financial service of the infante Ferdinand of Portugal, who by his will (1437) ordered the repayment to him of the vast sum of 506,000 reis blancs. Later he was apparently in the service of the duke of Braganza. His export business also brought him into trade relations with Flanders. He was father of Don Isaac *Abrabanel and grandfather of Judah *Abrabanel (Leone Ebreo) and Samuel *Abrabanel.

ABRABANEL, BENVENIDA

(also known as Benvegnita, Bienvenita; c. 1473-after 1560), one of the most influential and wealthiest Jewish women of early modern Italy. Benvenida was the daughter of Jacob Abrabanel (d. 1528), one of three brothers of Isaac *Abrabanel (1437-1508). She married Isaac’s youngest son, Samuel (1473-1547), bringing a very large dowry. By 1492, Benvenida and much of the family had settled in Naples, where her father and then her husband led the Jewish community. Benvenida appears to have raised six children of her own along with an illegitimate son of Samuel’s. One of her adult daughters lived in Lisbon, apparently as a Crypto-Jew, and was known for her charity and piety. Eleanora de Toledo (1522-1562), the second daughter of Pedro de Toledo, who became Viceroy of the Spanish rulers of Naples in 1532, was also raised in Benvenida’s house. Benvenida was renowned for her religious observance and her generosity; she fasted daily and ransomed at least a thousand captives. In 1524-25, Benvenida became an enthusiastic supporter of the messianic pretender David *Reuveni (d. 1538); she sent him money three times, as well as an ancient silk banner with the Ten Commandments written in gold on both sides, and a Turkish gown of gold. In 1533, Benvenida and several Neapolitan princesses successfully petitioned Emperor Charles v to delay the expulsion of the Jews of Naples for ten years. The Abrabanels left Naples in 1541 when Jews were required to wear a badge, and ultimately settled in Ferrara, a major Sephardi refuge. Dona Gracia (*Nasi) Mendes (c. 1510-1569) settled in Ferrara in 1548; although it is not known if the two women ever met, the interests of their families did not always coincide. In 1555-56, when Dona Gracia attempted to persuade Ottoman Jewish merchants to boycott the papal port of Ancona, the Abrabanel family, particularly Benvenida’s son Jacob, took the side of Ancona. Samuel Abrabanel died in 1547 leaving a will filed with and witnessed by Christians in which Benvenida was made general heir to all his movable and immovable property. Samuel’s illegitimate son challenged the will on the rabbinic grounds that a woman cannot inherit; from 1550 to 1551, this became a major dispute among the rabbis of Italy and Turkey. Despite this controversy, Benvenida took over Samuel’s business affairs, receiving permission from the Florentine authorities to open five banking establishments in Tuscany with her two sons, Jacob and Judah. Later she quarreled with Judah over his marriage and cut him off completely in 1553. Although Benvenida wielded great power, she herself left very few words in the historical record. Beyond a defense of women receiving gifts attributed to her, one folk remedy in her name is found in a British Library manuscript.

ABRABANEL, ISAAC BEN JUDAH

(1437-1508), statesman, biblical exegete, and theologian. Offshoot of a distinguished Ibero-Jewish family, Abrabanel (the family name also appears as Abravanel, Abarbanel, Bravanel, etc.) spent 45 years in Portugal, then passed the nine years immediately prior to Spanish Jewry’s 1492 expulsion in Castile. At that time an important figure at the court of Ferdinand and Isabella, he chose Italian exile over conversion to Christianity. He spent his remaining years in various centers in Italy where he composed most of his diverse literary corpus, a combination of prodigious biblical commentaries and involved theological tomes.

Like his father Judah, Abrabanel engaged successfully in both commerce and state finance while in Lisbon. After his father died he succeeded him as a leading financier at the court of King Alfonso v of Portugal. His importance at court was not restricted to his official sphere of activities. Of a loan to the state of 12,000,000 reals raised from both Jews and Christians in 1480, more than one-tenth was contributed by Abrabanel himself. When in 1471, 250 Jewish captives were brought to Portugal after the capture of Arcila and Tangier in North Africa by Alfonso v, Abrabanel was among those who headed the committee which was formed in Lisbon to raise the ransom money.

Abrabanel launched his literary career in Lisbon as well. In addition to a short philosophic essay entitled "The Forms of the Elements" (Z urot ha-Yesodot), he wrote his first work of biblical exegesis, a commentary on a challenging section in the Book of Exodus (Ateret Zekenim ("Crown of the Elders")), and began a commentary on the Book of Deuteronomy (Mirkevet ha-Mishneh ("Second Chariot")) as well as a work on prophecy (Mahazeh Shaddai ("Vision of the Almighty")). He was also in touch with cultured Christian circles. His connections with members of the aristocracy were not founded only on business but also on the affinity of humanism. His letter of condolence to the count of Faro on the death of the latter’s father, written in Portuguese, provides a striking example of this relationship.

The period of tranquillity in Lisbon ended with the death of Alfonso v in 1481. His heir, Joao 11 (1481-1495), was determined to deprive the nobility of their power and to establish a centralized regime. The nobles, led by the king’s brother-in-law, the duke of Bragan^a, and the count of Faro, rebelled against him, but the insurrection failed. Abrabanel was also suspected of conspiracy and forced to escape (1483). Although denying guilt, he was sentenced to death in absentia (1485). He evidently managed to transfer a substantial part of his fortune to Castile, and stayed there for a while in the little town of Segura de la Orden near the Portuguese border. Thereafter, Abrabanel quickly established himself as a leading financier and royal servant. By 1485, he had relocated to the Spanish heartland at Alcala de Henares in order to oversee tax-farming operations for Cardinal Pedro Gonzalez de Mendoza, the "third king of Spain." The initial total involved was the vast sum of 6,400,000 maravedis, with Abrabanel earning 118,500 mara-vedis per year as commission. As collateral he put up, without restriction, all that he owned. Abrabanel also supported the campaign of Ferdinand and Isabella against Granada, Islam’s last Iberian citadel, offering extensive loans.

Ferdinand’s and Isabella’s signing of an order of expulsion against Jews in Spain and her possessions took Abrabanel by surprise. After the edict of expulsion had been signed, on March 31, 1492, Abrabanel was among those who tried in vain to obtain its revocation. Abrabanel relinquished his claim to certain sums of money which he had advanced to Ferdinand and Isabella against tax-farming revenues, which he had not yet managed to recover. In return he was allowed to take 1000 gold ducats and various gold and silver valuables out of the country with him (May 31, 1492).

Though occupied with worldly affairs, Abrabanel continued to pursue scholarship and produce works in Spain. Most notably, he composed commentaries on Joshua, Judges, and Samuel soon after arriving in Castile. Among other things, these commentaries attest to Abrabanel’s novel approaches to questions concerning the authorship and origins of biblical books, some of which imply the impress of a humanist sense of historicity on his exegesis. Seen from this vantage-point, these commentaries offer perhaps the earliest example of Renaissance stimulus in works of Hebrew literature composed beyond Italy.

After the 1492 expulsion, Abrabanel passed two years in Naples. Here he completed his commentary on Kings (fall 1493). But he was again prevented from devoting his time to study for long, eventually coming to serve in the court of Alfonso 11. Abrabanel tells of wealth recouped in Italy and renewed fame "akin to that of all of the magnates in the land." Abrabanel’s fortunes turned again, however, when the French sacked Naples (1494). His library was destroyed. Before departing Naples, Abrabanel managed to complete a work on dogma (Rosh Amanah ("Principles of Faith")) structured around Maimonides’ enumeration of 13 foundational principles of Judaism. Abrabanel now followed the royal family to Messina, remaining there until 1495. Subsequently he removed to Corfu where he began his commentaries on Isaiah and the Minor Prophets (summer 1495) and then to Monopoli (Apulia), where early in 1496 he completed the commentary on Deuteronomy which he had begun in Lisbon, as well as his commentaries on the Passover Haggadah (Zevah Pesah), and on Avot (NahalatAvot). Of the same period are his works expressing the hopes for redemption which at times explain contemporary events as messianic tribulations – Ma’yenei Yeshuah, Yeshu’ot Meshiho, and Mashmia Yeshuah. Two other works addressed the problem of the world’s createdness, Shamayim Hadashim ("New Heavens") and Mifalot Elohim ("Wonders of the Lord"). In 1503, Abrabanel settled at last in Venice. He was engaged in negotiations between the Venetian senate and the kingdom of Portugal in that year, for a commercial treaty to regulate the spice trade. He now finished commentaries on Jeremiah and Ezekiel, Genesis and Exodus, and Leviticus and Numbers. In a reply to an enquiry from Saul ha-Kohen of Candia, he mentions that he was engaged in composing his book ZZedek Olamim, on recompense and punishment, and Lahakat ha-Nevi’im, on prophecy (a new version of Mahazeh Shaddai which had been lost in Naples), and in completing his commentary on Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed. Abrabanel died in Venice and was buried in Padua. Owing to the destruction of the Jewish cemetery there during the wars in 1509, his grave is unknown.

Abrabanel as Biblical Exegete

Though Abrabanel’s writings traverse many fields, they mainly comprise works of scriptural interpretation. It was in his role as a biblical interpreter that Abrabanel was most emphatic about his originality as a writer.

In his general prologue to his commentaries on the Former Prophets, Abrabanel spelled out some of his main procedures and aims as an interpreter of Scripture. To ease the task of explaining biblical narratives, Abrabanel would "divide each of the books into pericopes." These would be smaller than the units devised by his 14th century Jewish predecessor, Ger-sonides, but larger than the ones fashioned by "the scholar Jerome, who translated Holy Writ for the Christians." Before explaining a pericope, he would raise questions or "doubts" about it. Overall, Abrabanel’s interpretive aim was twofold: explanation of the verses "in the most satisfactory way possible" and exploration of "the conceptual problems embedded therein to their very end." In short, he would explore both Scripture’s exegetical and doctrinal-theological dimensions. Abrabanel warns that such interpretation yields lengthy commentary. In his commentary on the Pentateuch these questions have no fixed number, sometimes amounting to over 40, but in his commentary to the Prophets he limits himself to six. Despite the marked artificiality of this method, Abrabanel states that he chose it as a means of initiating discussion and encouraging investigation.

Abrabanel’s exegesis combines a quest for Scripture’s contextual sense (peshat) with other levels of interpretation. His repeated and emphatic statements about the primacy of peshat notwithstanding, Abrabanel incorporates midrashim into his commentaries often and occasionally digresses into detailed explanations of them. At the same time, he says that he describes Rashi’s overindulgence in midrashic interpretation as "evil and bitter." Like some geonim and Spanish interpreters before him, Abrabanel distinguishes rabbinic dicta that reflect a "received tradition," which he says are indubitably true and hence binding, from midrashim that reflect fallible human reasoning. The latter can be rejected. Abrabanel’s criticisms of individual midrashim can be unusually blunt ("very unlikely," "evidently weak," and so forth) even as Abrabanel often uses Midrash as a vehicle to extract maximal insight and meaning from the biblical word.

Abrabanel’s commentaries evince a dialogue with a wide variety of earlier commentators. The predecessor who most shaped his exegetical program was *Nahmanides. Like this earlier Spanish scholar, Abrabanel devotes considerable attention to questions of scripture’s literary structure and argues for the biblical text’s chronological sequentiality wherever possible.

Abrabanel was ambivalent about philosophically oriented biblical interpretation as practiced by Maimonides and his rationalist successors. He vehemently fought the extreme rationalism of philosophical interpretation (for example in Joshua 10, Second Excursus) as well as interpretations based on philosophical allegory. At the same time he himself had recourse, especially in his commentary on the Pentateuch, to numerous interpretations based on philosophy, as when he interprets the paradise story. Abrabanel refers to kabbalistic interpretation only rarely.

At times, he points to errors and moral failings in the heroes of the Bible. For example, he criticizes certain actions of David and Solomon and points out some stylistic and linguistic defects of Jeremiah and Ezekiel.

Among the innovations in Abrabanel’s exegesis are the following:

(1) His comparison of the social structure of society in biblical times with that of the European society in his day (for example, in dealing with the institution of monarchy, 1 Samuel 8). He had wide recourse to historical interpretation, particularly in his commentaries to the Major and Minor Prophets and to the Book of Daniel.

(2) Preoccupation with Christian exegesis. He disputed christological interpretations, but he did not hesitate to borrow from Christian writers when their interpretation seemed correct to him.

(3) His introductions to the books of the prophets, which are much more comprehensive than those of his predecessors. In them he deals with the content of the books, the division of the material, their authors and the time of their compilation, and also draws comparisons between the method and style of the various prophets. His investigations at once reflect the spirit of medieval scholasticism and incipient Renaissance humanism.

Abrabanel’s commentaries were closely studied by a wide variety of later Jewish scholars, such as the 19th-century biblical interpreter Meir Loeb ben Jehiel Michael (*Malbim), as well as by many Christian thinkers from the 16th through 18th centuries, some of whom translated excerpts from his biblical commentaries into Latin.

Abrabanel’s Thought

The religious thought of Abrabanel appears in no single volume, but is distributed throughout his works. His religious teachings reflect ongoing dialogues with the major figures of earlier medieval Jewish theology, especially Maimonides. Abrabanel typically evaluates earlier views on a given issue, and then sets forth his own teachings. In doing so, he displays considerable philosophic depth and theological erudition. Among Abrabanel’s main theological concerns were the world’s creation, prophecy, history, politics, and eschatology.

Creation. God’s creation of the world ex nihilo stands as the Archimedean point of Abrabanel’s religious thought. This view, which alone conforms to the teaching of the Torah, is also sustained by arguments from reason. Abrabanel refutes a number of competing cosmogonies influenced by different streams in ancient and medieval philosophy: the idea of the visible world’s eternity, associated in the Middle Ages with Aristotle; the hypothesis of its creation from eternal matter, associated with Plato; and the doctrine of eternal creation. Abrabanel’s teaching that God voluntarily created the world from nothing informs his understanding of the universe as a place ruled by God’s infinite power in which the miracles of the Bible occurred according to their literal description.

Prophecy. Prophecy is another cornerstone of Abrabanel’s theology. The form in which Abrabanel discusses prophecy is influenced by the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic cosmology and the medieval Jewish philosophers who preceded him, particularly Maimonides. The influence of the latter was largely negative rather than positive, a stimulus that provoked a negative response, but which shaped the character of that response.

Abrabanel vigorously attacked the naturalistic view of prophecy and Judaism advanced by Maimonides, notably in his commentary on the Guide (2:32-45). According to this view, prophecy is a natural function of human beings that arises from an individual’s achievement of moral, and especially intellectual, perfection. By contrast, Abrabanel argues that prophecy is an essentially supernatural phenomenon in which the prophet is chosen by God. As the miraculous creation of God, prophecy supplies insight that is qualitatively superior to natural or scientific knowledge: the latter is probable and refragable, whereas the former is certain and infallible.

History. Abrabanel bases his understanding of history upon the Scriptures, which has been established as a perfect source of truth. This is the history of the universe as well as of man. The foundation is the personal God who creates the universe ex nihilo. As such, the universe presents no pre-existent nature to limit the absolute power of God. Neither does God relinquish control over the universe to nature, which, intervening between God and man, exercises a mechanical providence over humanity. Abrabanel thus rejects the naturalism of Maimonides and his followers adopted from the Neoplatonized Aristotelianism of medieval science. What befalls man is directly attributable to God, human freedom, or supernatural beings. The major outlines of Abrabanel’s theory of history correspond essentially with the rabbinic view. God created the universe according to a grand design which culminates in the salvation of righteous mankind and the vindication of Judaism. Adam was created by God and placed in Eden to realize his spiritual potentialities. Instead, he chose to disobey God by eating of the forbidden tree of knowledge. For this sin, Adam became subject to death and was condemned to live on an inhospitable earth. Ultimately, through Noah, Abraham, and Jacob, the people Israel was developed to continue God’s plan of salvation. God exercised a special providence over them, revealing the Torah and giving them the land of Israel, which was perfectly suited for spiritual realization and the reception of prophecy. Yet the Jews sinned against God, and after the destruction of the First Temple were sent into exile, which will continue until the advent of the Messianic Age when the history of this universe will come to an end.

Politics. Some of Abrabanel’s most trenchant ideas lie in the sphere of politics. The view of Abrabanel on government reflects his religious convictions. The need for the state is temporal, arising with the expulsion of Adam from Eden and ending in the Messianic Age. As a product of spiritual exile, no state is perfect, some are better than others, but none provides salvation. The best possible state serves the spiritual as well as the political needs of its people, as does the state based on the principles of Mosaic law. In his commentaries on Scripture, Abrabanel presents somewhat conflicting views of the optimum society. However, its basic structure along Mosaic lines is presented clearly in his comments upon Deuteronomy 16:18. Two legal systems are provided for, civil and ecclesiastical. The civil system consists of lower courts, a superior court, and the king; the ecclesiastical system consists of levites, priests, and prophets. The officials of the lower courts, which possessed municipal jurisdiction, were chosen by the people. The superior court or Sanhedrin, possessed national jurisdiction, and was appointed by the king, primarily from among the priests and levites. A significant feature of Abrabanel’s political convictions generally is seen in this structure: the diffusion of political power. Abrabanel’s distrust of concentrated authority is echoed in his intensely negative opinion of monarchy. He considered monarchy a demonstrable curse, and the insistence of ancient Israel upon human kings in place of God’s (theocratic) sovereignty, a sin for which it paid dearly. Monarchy’s inferiority as a form of government is demonstrable on philosophic and not only on scriptural grounds.

Eschatology. Abrabanel produced a substantial eschato-logical corpus several years after his arrival in Italy. As part of an exhaustive study of the classical (biblical-rabbinic) and medieval Jewish eschatological tradition, he set forth a powerful messianic message that included a specific forecast for the end of days, or for major events anticipating it: the year 1503. Spain’s expulsion of her Jews was one significant context for Abrabanel’s messianic writings. Christian missionizing based on christological interpretation of biblical and rabbinic sources was another. Just how convinced Abrabanel was by his undeniably vivid apocalyptic rhetoric is hard to say.

Abrabanel’s vision of the Messiah and of messianic times differs considerably from Maimonides’ naturalistic one. The Messiah will possess superhuman perfection. The days of the Messiah will see miracles in abundance such as unprecedented agricultural fertility. At that time the Jews will be revenged on their enemies in extraordinary ways, the dispersed Jews will return to Israel, the resurrection and judgment will take place, and all Jews will live in Israel under the Messiah, whose rule will extend over all mankind. Though it is often said that Abrabanel’s messianic speculations contributed significantly to the powerful messianic movements among the Jews in the 16th and 17th centuries, there is little evidence to support this claim.