The invention: An internal combustion engine in which ignition is achieved by the use of high-temperature compressed air, rather than a spark plug.

The people behind the invention:

Rudolf Diesel (1858-1913), a German engineer and inventor Sir Dugold Clark (1854-1932), a British engineer Gottlieb Daimler (1834-1900), a German engineer Henry Ford (1863-1947), an American automobile magnate Nikolaus Otto (1832-1891), a German engineer and Daimler’s teacher

A Beginning in Winterthur

By the beginning of the twentieth century, new means of providing society with power were needed. The steam engines that were used to run factories and railways were no longer sufficient, since they were too heavy and inefficient. At that time, Rudolf Diesel, a German mechanical engineer, invented a new engine. His diesel engine was much more efficient than previous power sources. It also appeared that it would be able to run on a wide variety of fuels, ranging from oil to coal dust. Diesel first showed that his engine was practical by building a diesel-driven locomotive that was tested in 1912.

In the 1912 test runs, the first diesel-powered locomotive was operated on the track of the Winterthur-Romanston rail line in Switzerland. The locomotive was built by a German company, Gesell-schaft fur Thermo-Lokomotiven, which was owned by Diesel and his colleagues. Immediately after the test runs at Winterthur proved its efficiency, the locomotive—which had been designed to pull express trains on Germany’s Berlin-Magdeburg rail line—was moved to Berlin and put into service. It worked so well that many additional diesel locomotives were built. In time, diesel engines were also widely used to power many other machines, including those that ran factories, motor vehicles, and ships.

Rudolf Diesel

Unbending, suspicious of others, but also exceptionally intelligent, Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel led a troubled life and came to a mysterious end. His parents, expatriate Germans, lived in Paris when he was born, 1858, and he spent his early childhood there. In 1870, just as he was starting his formal education, his family fled to England on the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, which turned the French against Germans. In England, Diesel spent much of his spare time in museums, educating himself. His father, a leather craftsman, was unable to support his family, so as a teenager Diesel was packed off to Augsburg, Germany, where he was largely on his own. Although these experiences made him fluent in English, French, and German, his was not a stable or happy childhood.

He threw himself into his studies, finishing his high school education three years ahead of schedule, and entered the Technical College of Munich, where he was the star student. Once, during his school years, he saw a demonstration of a Chinese firestick. The firestick was a tube with a plunger. When a small piece of flammable material was put in one end and the plunger pushed down rapidly toward it, the heat of the compressed air in the tube ignited the material. The demonstration later inspired Diesel to adapt the principle to an engine.

His was the first engine to run successfully with compressed air fuel ignition, but it was not the first design. So although he received the patent for the diesel engine, he had to fight challenges in court from other inventors over licensing rights. He always won, but the strain of litigation worsened his tendency to stubborn self-reliance, and this led him into difficulties. The first compression engines were unreliable and unwieldy, but Diesel rebuffed all suggestions for modifications, requiring that builders follow his original design. His attitude led to delays in development of the engine and lost him financial support.

In 1913, while crossing the English Channel aboard a ship, Diesel disappeared. His body was never found, and although the authorities concluded that Diesel committed suicide, no one knows what happened.

Diesels, Diesels Everywhere

In the 1890′s, the best engines available were steam engines that were able to convert only 5 to 10 percent of input heat energy to useful work. The burgeoning industrial society and a widespread network of railroads needed better, more efficient engines to help businesses make profits and to speed up the rate of transportation available for moving both goods and people, since the maximum speed was only about 48 kilometers per hour. In 1894, Rudolf Diesel, then thirty-five years old, appeared in Augsburg, Germany, with a new engine that he believed would demonstrate great efficiency.

The diesel engine demonstrated at Augsburg ran for only a short time. It was, however, more efficient than other existing engines. In addition, Diesel predicted that his engines would move trains faster than could be done by existing engines and that they would run on a wide variety of fuels. Experimentation proved the truth of his claims; even the first working motive diesel engine (the one used in the Winterthur test) was capable of pulling heavy freight and passenger trains at maximum speeds of up to 160 kilometers per hour.

By 1912, Diesel, a millionaire, saw the wide use of diesel locomotives in Europe and the United States and the conversion of hundreds of ships to diesel power. Rudolf Diesel’s role in the story ends here, a result of his mysterious death in 1913—believed to be a suicide by the authorities—while crossing the English Channel on the steamer Dresden. Others involved in the continuing saga of diesel engines were the Britisher Sir Dugold Clerk, who improved diesel design, and the American Adolphus Busch (of beer-brewing fame), who bought the North American rights to the diesel engine.

The diesel engine is related to automobile engines invented by Nikolaus Otto and Gottlieb Daimler. The standard Otto-Daimler (or Otto) engine was first widely commercialized by American auto magnate Henry Ford. The diesel and Otto engines are internal-combustion engines. This means that they do work when a fuel is burned and causes a piston to move in a tight-fitting cylinder. In diesel engines, unlike Otto engines, the fuel is not ignited by a spark from a spark plug. Instead, ignition is accomplished by the use of high-temperature compressed air.

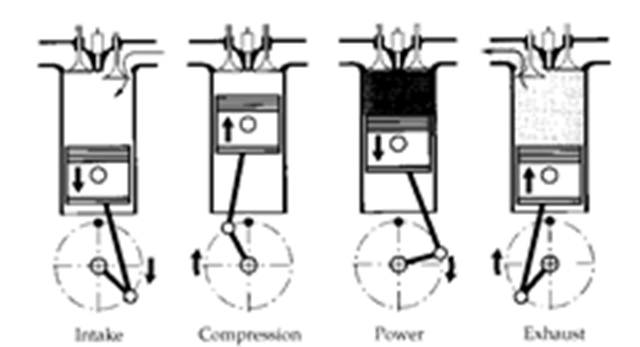

The four strokes of a diesel engine.

In common “two-stroke” diesel engines, pioneered by Sir Dug-old Clerk, a starter causes the engine to make its first stroke. This draws in air and compresses the air sufficiently to raise its temperature to 900 to 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. At this point, fuel (usually oil) is sprayed into the cylinder, ignites, and causes the piston to make its second, power-producing stroke. At the end of that stroke, more air enters as waste gases leave the cylinder; air compression occurs again; and the power-producing stroke repeats itself. This process then occurs continuously, without restarting.

Impact

Proof of the functionality of the first diesel locomotive set the stage for the use of diesel engines to power many machines. Although Rudolf Diesel did not live to see it, diesel engines were widely used within fifteen years after his death. At first, their main applications were in locomotives and ships. Then, because diesel engines are more efficient and more powerful than Otto engines, they were modified for use in cars, trucks, and buses.

At present, motor vehicle diesel engines are most often used in buses and long-haul trucks. In contrast, diesel engines are not as popular in automobiles as Otto engines, although European auto-

makers make much wider use of diesel engines than American automakers do. Many enthusiasts, however, view diesel automobiles as the wave of the future. This optimism is based on the durability of the engine, its great power, and the wide range and economical nature of the fuels that can be used to run it. The drawbacks of diesels include the unpleasant odor and high pollutant content of their emissions.

Modern diesel engines are widely used in farm and earth-moving equipment, including balers, threshers, harvesters, bulldozers,rock crushers, and road graders. Construction of the Alaskan oil pipeline relied heavily on equipment driven by diesel engines. Diesel engines are also commonly used in sawmills, breweries, coal mines, and electric power plants.

Diesel’s brainchild has become a widely used power source, just as he predicted. It is likely that the use of diesel engines will continue and will expand, as the demands of energy conservation require more efficient engines and as moves toward fuel diversification require engines that can be used with various fuels.

See also Bullet train; Gas-electric car; Internal combustion engine.