Abstract

Commissioning is the methodology for bringing to light design errors, equipment malfunctions, and improper control strategies at the most cost-effective time to implement corrective action. The primary goal of commissioning is to achieve optimal building systems performance. There are two types of commissioning: acceptance-based and process-based. Process-based commissioning is a comprehensive process that begins in the predesign phase and continues through post acceptance, while acceptance-based commissioning, which is perceived to be the cheaper method, basically examines whether an installation is compliant with the design and accordingly achieves more limited results.

Commissioning originated in the early 1980s in response to a large increase in construction litigation. Commissioning was the result of owners seeking other means to gain assurance that they were receiving systems compliant with the design intent and with the performance characteristics and quality specified. Learn how commissioning has evolved and the major initiatives that are driving its growing acceptance.

The general rule for including a system in the commissioning process is: the more complicated the system is, the more compelling is the need to include it in the commissioning process. Other criteria for determining which systems should be included are discussed. Discover the many benefits of commissioning, such as improved quality assurance, dispute avoidance, and contract compliance.

Selection of the commissioning agent is key to the success of the commissioning plan. Learn what traits are necessary and what approaches to use for the selection process.

The commissioning process occurs over a variety of clearly delineated phases. The phases of the commissioning process as defined below are discussed in detail: predesign, design, construction/ installation, acceptance, and postacceptance.

Extensive studies analyzing the cost/benefit of commissioning justify its application. One study defines the median commissioning cost for new construction as $1 per square foot or 0.6% of the total construction cost. The median simple payback for new construction projects utilizing commissioning is 4.8 years.

Understand how to achieve the benefits of commissioning, including optimization of building performance, reduction of facility life-cycle cost, and increased occupant satisfaction.

INTRODUCTION

This entry provides an overview of commissioning—the processes one employs to optimize the performance characteristics of a new facility being constructed. Commissioning is important to achieve customer satisfaction, optimal performance of building systems, cost containment, and energy efficiency, and it should be understood by contractors and owners.

After providing an overview of commissioning and its history and prevalence, this entry discusses what systems should be part of the commissioning process, the benefits of commissioning, how commissioning is conducted, and the individuals and teams critical for successful commissioning. Then the entry provides a detailed discussion of each of the different phases of a successful commissioning process, followed by a discussion of the common mistakes to avoid and how one can measure the success of a commissioning effort, together with a cost-benefit analysis tool.

The purpose of this entry will be realized if its readers decide that successful commissioning is one of the most important aspects of construction projects and that commissioning should be managed carefully and deliberately throughout any project, from predesign to post-acceptance. As an introduction to those unfamiliar with the process and as a refresher for those who are, the following section provides an overview of commissioning, how it developed, and its current prevalence today.

OVERVIEW OF COMMISSIONING

Commissioning Defined

Commissioning is the methodology for bringing to light design errors, equipment malfunctions, and improper control strategies at the most cost-effective time to implement corrective action. Commissioning facilitates a thorough understanding of a facility’s intended use and ensures that the design meets the intent through coordination, communication, and cooperation of the design and installation team. Commissioning ensures that individual components function as a cohesive system. For these reasons, commissioning is best when it begins in the predesign phase of a construction project and can in one sense be viewed as the most important form of quality assurance for construction projects.

Unfortunately, there are many misconceptions associated with commissioning, and perhaps for this reason, commissioning has been executed with varying degrees of success, depending on the level of understanding of what constitutes a “commissioned” project. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (AHSRAE) guidelines define commissioning as: the process of ensuring that systems are designed, installed, functionally tested, and capable of being operated and maintained to perform conformity with the design intent… [which] begins with planning and includes design, construction, startup, acceptance, and training, and is applied throughout the life of the building.[4] However, for many contractors and owners, this definition is simplified into the process of system startup and checkout or completing punch-list items.

Of course, a system startup and checkout process carried out by a qualified contractor is one important aspect of commissioning. Likewise, construction inspection and the generation and completion of punch-list items by a construction manager are other important aspects of commissioning. However, it takes much more than these standard installation activities to have a truly “commissioned” system. Commissioning is a comprehensive and methodical approach to the design and implementation of a cohesive system that culminates in the successful turnover of the facility to maintenance staff trained in the optimal operation of those systems.

Without commissioning, a contractor starts up the equipment but doesn’t look beyond the startup to system operation. Assessing system operation requires the contractor to think about how the equipment will be used under different conditions. As one easily comprehended example, commissioning requires the contractor to think about how the equipment will operate as the seasons change. Analysis of the equipment and building systems under different load conditions due to seasonal conditions at the time of system startup will almost certainly result in some adjustments to the installed equipment for all but the most benign climates. However, addressing this common requirement of varying load due to seasonal changes most likely will not occur without commissioning. Instead, the maintenance staff is simply handed a building with minimal training and left to figure out how to achieve optimal operation on their own. In this seasonal example, one can just imagine how pleased the maintenance staff would be with the contractor when a varying load leads to equipment or system failure—often under very hot or very cold conditions!

Thus, the primary goal of commissioning is to achieve optimal building systems performance. For heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems, optimal performance can be measured by thermal comfort, indoor air quality, and energy savings. Energy savings, however, can result simply from successful commissioning targeted at achieving thermal comfort and excellent indoor air quality. Proper commissioning will prevent HVAC system malfunction—such as simultaneous heating and cooling, and overheating or over-cooling—and successful malfunction prevention translates directly into energy savings. Accordingly, energy savings rise with increasing comprehensiveness of the commissioning plan. Commissioning enhances energy performance (savings) by ensuring and maximizing the performance of specific energy efficiency measures and correcting problems causing excessive energy use.[3] Commissioning, then, is the most cost-effective means of improving energy efficiency in commercial buildings. In the next section, the two main types of commissioning in use today—acceptance-based and processed-based—are compared and contrasted.

Acceptance-Based vs Process-Based Commissioning

Given the varied nature of construction projects, contractors, owners, buildings, and the needs of the diverse participants in any building projection, commissioning can of course take a variety of forms. Generally, however, there are two types of commissioning: acceptance-based and process-based. Process-based commissioning is a comprehensive process that begins in the predesign phase and continues through postacceptance, while acceptance-based commissioning, which is perceived to be the cheaper method, basically examines whether an installation is compliant with the design and accordingly achieves more limited results.

Acceptance-based commissioning is the most prevalent type due to budget constraints and the lack of hard cost/ benefit data to justify the more extensive process-based commissioning. Acceptance-based commissioning does not involve the contractor in the design process but simply constitutes a process to ensure that the installation matches the design. In acceptance-based commissioning, confrontational relationships are more likely to develop between the commissioning agent and the contractor because the commissioning agent and the contractor, having been excluded from the design phase, have not “bought in” to the design and thus may be more likely to disagree in their interpretation of the design intent.

Because the acceptance-based commissioning process simply validates that the installation matches the design, installation issues are identified later in the cycle.

Construction inspection and regular commissioning meetings do not occur until late in the construction/installation phase with acceptance-based commissioning. As a result, there is no early opportunity to spot errors and omissions in the design, when remedial measures are less costly to undertake and less likely to cause embarrassment to the designer and additional costs to the contractor. As most contractors will readily agree, addressing issues spotted in the design or submittal stages of construction is typically much less costly than addressing them after installation, when correction often means tearing out work completed and typically delays the completion date.

Acceptance-based commissioning is cheaper, however, at least on its face, being approximately 80% of the cost of process-based commissioning.1-2-1 If only the initial cost of commissioning services is considered, many owners will conclude that this is the most cost-effective commissioning approach. However, this 20% cost differential does not take into account the cost of correcting defects after the fact that process-based commissioning could have identified and corrected at earlier stages of the project. One need encounter only a single, expensive-to-correct project to become a devotee of process-based commissioning.

Process-based commissioning involves the commissioning agent in the predesign through the construction, functional testing, and owner training. The main purpose is quality assurance—assurance that the design intent is properly defined and followed through in all phases of the facility life cycle. It includes ensuring that the budget matches the standards that have been set forth for the project so that last-minute “value engineering” does not undermine the design intent, that the products furnished and installed meet the performance requirements and expectation compliant with the design intent, and that the training and documentation provided to the facility staff equip them to maintain facility systems true to the design intent.

As the reader will no doubt already appreciate, the author believes that process-based commissioning is far more valuable to contractors and owners than acceptance-based commissioning. Accordingly, the remainder of this entry will focus on process-based commissioning, after a brief review of the history of commissioning from inception to date, which demonstrates that our current, actively evolving construction market demands contractors and contracting professionals intimately familiar with and expert in conducting process-based commissioning.

History of Commissioning

Commissioning originated in the early 1980s in response to a large increase in construction litigation. Owners were dissatisfied with the results of their construction projects and had recourse only to the courts and litigation to resolve disputes that could not be resolved by meeting directly with their contractors. While litigation attorneys no doubt found this satisfactory approach to resolving construction project issues, owners did not, and they actively began looking for other means to gain assurance that they were receiving systems compliant with the design intent and with the performance characteristics and quality specified. Commissioning was the result.

While commissioning enjoyed early favor and wide acceptance, the recession of the mid-1980s placed increasing market pressure on costs, and by the mid-to late 1980s it forced building professionals to reduce fees and streamline services. As a result, acceptance-based commissioning became the norm, and process-based commissioning became very rare. This situation exists in most markets today; however, the increasing cost of energy, the growing awareness of the global threat of climate change and the need to reduce CO2 emissions as a result, and the legal and regulatory changes resulting from both are creating a completely new market in which process-based commissioning will become ever more important, as discussed in the following section.

Prevalence of Commissioning Today

There are varying degrees of market acceptance of commissioning from state to state. Commissioning is in wide use in California and Texas, for example, but it is much less widely used in many other states. The factors that impact the level of market acceptance depend upon:

• The availability of commissioning service providers

• State codes and regulations

• Tax credits

• Strength of the state’s economy1-1-1

State and federal policies with regard to commissioning are changing rapidly to increase the demand for commissioning. Also, technical assistance and funding are increasingly available for projects that can serve as demonstration projects for energy advocacy groups. The owner should investigate how each of these factors could benefit the decision to adopt commissioning in future construction projects.

Some of the major initiatives driving the growing market acceptance of commissioning are:

• Federal government’s U.S. Energy Policy Act of 1992 and Executive Order 12902, mandating that federal agencies develop commissioning plans

• Portland Energy Conservation, Inc.; National Strategy for Building Commissioning; and their annual conferences

• ASHRAE HVAC Commissioning Guidelines (1989)

• Utilities establishing commissioning incentive programs

• Energy Star building program

• Leadership in Energy Environmental Design (LEED) certification for new construction

• Building codes

• State energy commission research programs

Currently, the LEED is having the largest impact in broadening the acceptance of commissioning. The Green Building Council is the sponsor of LEED and is focused on sustainable design—design and construction practices that significantly reduce or eliminate the cradle-to-grave negative impacts of buildings on the environment and building occupants. Leadership in energy efficient design encourages sustainable site planning, conservation of water and water efficiency, energy efficiency and renewable energy, conservation of materials and resources, and indoor environmental quality.

With this background on commissioning, the various components of the commissioning process can be explored, beginning with an evaluation of what building systems should be subject to the commissioning process.[5]

COMMISSIONING PROCESS

Systems to Include in the Commissioning Process

The general rule for including a system in the commissioning process is: the more complicated the system is the more compelling is the need to include it in the commissioning process. Systems that are required to integrate or interact with other systems should be included. Systems that require specialized trades working independently to create a cohesive system should be included, as well as systems that are critical to the operation of the building. Without a commissioning plan on the design and construction of these systems, installation deficiencies are likely to create improper interaction and operation of system components.

For example, in designing a lab, the doors should be included in the commissioning process because determining the amount of leakage through the doorways could prove critical to the ability to maintain critical room pressures to ensure proper containment of hazardous material. Another common example is an energy retrofit project. Such projects generally incorporate commissioning as part of the measurement and verification plan to ensure that energy savings result from the retrofit process.

For any project, the owner must be able to answer the question of why commissioning is important.

Why Commissioning?

A strong commissioning plan provides quality assurance, prevents disputes, and ensures contract compliance to deliver the intended system performance. Commissioning is especially important for HVAC systems that are present in virtually all buildings because commissioned HVAC systems are more energy efficient.

The infusion of electronics into almost every aspect of modern building systems creates increasingly complex systems requiring many specialty contractors. Commissioning ensures that these complex subsystems will interact as a cohesive system.

Commissioning identifies design or construction issues and, if done correctly, identifies them at the earliest stage in which they can be addressed most cost effectively. The number of deficiencies in new construction exceeds existing building retrofit by a factor of 3.[3] Common issues that can be identified by commissioning that might otherwise be overlooked in the construction and acceptance phase are: air distribution problems (these occur frequently in new buildings due to design capacities, change of space utilization, or improper installation), energy problems, and moisture problems.

Despite the advantages of commissioning, the current marketplace still exhibits many barriers to adopting commissioning in its most comprehensive and valuable forms.

Barriers to Commissioning

The general misperception that creates a barrier to the adoption of commissioning is that it adds extra, unjustified costs to a construction project. Until recently, this has been a difficult perception to combat because there are no energy-use baselines for assessing the efficiency of a new building. As the cost of energy continues to rise, however, it becomes increasingly less difficult to convince owners that commissioning is cost effective. Likewise, many owners and contractors do not appreciate that commissioning can reduce the number and cost of change orders through early problem identification. However, once the contractor and owner have a basis on which to compare the benefit of resolving a construction issue earlier as opposed to later, in the construction process, commissioning becomes easier to sell as a win-win proposal.

Finding qualified commissioning service providers can also be a barrier, especially in states where commissioning is not prevalent today. The references cited in this entry provide a variety of sources for identifying associations promulgating commissioning that can provide referrals to qualified commissioning agents.

For any owner adopting commissioning, it is critical to ensure acceptance of commissioning by all of the design construction team members. Enthusiastic acceptance of commissioning by the design team will have a very positive influence on the cost and success of your project. An objective of this entry is to provide a source of information to help gain such acceptance by design construction team members and the participants in the construction market.

Selecting the Commissioning Agent

Contracting an independent agent to act on behalf of the owner to perform the commissioning process is the best way to ensure successful commissioning. Most equipment vendors are not qualified and are likely to be biased against discovering design and installation problems—a critical function of the commissioning agent—with potentially costly remedies. Likewise, systems integrators have the background in control systems and data exchange required for commissioning but may not be strong in mechanical design, which is an important skill for the commissioning agent. Fortunately, most large mechanical consulting firms offer comprehensive commissioning services, although the desire to be competitive in the selection processes sometimes forces these firms to streamline their scope on commissioning.

Owners need to look closely at the commissioning scope being offered. An owner may want to solicit commissioning services independently from the selection of the architect/mechanical/electrical/plumbing design team or, minimally, to request specific details on the design team’s approach to commissioning. If an owner chooses the same mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) firm for design and commissioning, the owner should ensure that there is physical separation between the designer and commissioner to ensure that objectivity is maintained in the design review stages. An owner should consider taking on the role of the commissioning agent directly, especially if qualified personnel exist in-house. This approach can be very cost effective. The largest obstacles to success with an in-house commissioning agent are the required qualifications and the need to dedicate a valuable resource to the commissioning effort. Many times, other priorities may interfere with the execution of the commissioning process by an in-house owner’s agent.

There are three basic approaches to selecting the commissioning agent:

Negotiated—best approach for ensuring a true partnership

Selective bid list—preapproved list of bidders

Competitive—open bid list

Regardless of the approach, the owner should clearly define the responsibilities of the commissioning agent at the start of the selection process. Fixed-cost budgets should be provided by the commissioning agent to the owner for the predesign and design phases of the project, with not-to-exceed budgets submitted for the construction and acceptance phases. Firm service fees should be agreed upon as the design is finalized.

Skills of a Qualified Commissioning Agent

A commissioning agent needs to be a good communicator, both in writing and verbally. Writing skills are important because documentation is critical to the success of the commissioning plan. Likewise, oral communication skills are important because communicating issues uncovered in a factual and nonaccusatory manner is most likely to resolve those issues efficiently and effectively. The commissioning agent should have practical field experience in MEP controls design and startup to be able to identify potential issues early. The commissioning agent likewise needs a thorough understanding of how building structural design impacts building systems. The commissioning agent must be an effective facilitator and must be able to decrease the stress in stressful situations. In sum, the commissioning agent is the cornerstone of the commissioning team and the primary determinant of success in the commissioning process.

At least ten organizations offer certifications for commissioning agents. However, there currently is no industry standard for certifying a commissioning agent. Regardless of certification, the owner should carefully evaluate the individuals to be performing the work from the commissioning firm selected. Individual experience and reputation should be investigated. References for the lead commissioning agent are far more valuable than references for the executive members of a commissioning firm in evaluating potential commissioning agents. The commissioning agent selected will, however, only be one member of a commissioning team, and the membership of the commissioning team is critical to successful commissioning.

Commissioning Team

The commissioning team is composed of representatives from all members of the project delivery team: the commissioning agent, representatives of the owner’s maintenance team, the architect, the MEP designer, the construction manager, and systems contractors. Each team member is responsible for a particular area of expertise, and one important function of the commissioning agent is to act as a facilitator of intrateam communication.

The maintenance team representatives bring to the commissioning team the knowledge of current operations, and they should be involved in the commissioning process at the earliest stage, defining the design intent in the predesign phase, as described below. Early involvement of maintenance team representatives ensures a smooth transition from construction to a fully operational facility, and aids in the acceptance and full use of the technologies and strategies that have been developed during the commissioning process. Involvement of the maintenance team representatives also shortens the building turnover transition period.

The other members of the commissioning team have defined and important functions. The architect leads the development of the design intent document (DID). The MEP designer’s responsibilities are to develop the mechanical systems that support the design intent of the facility and comply with the owner’s current operating standards. The MEP schematic design is the basis for the systems installed and is discussed further below. The construction manager ensures that the project installation meets the criteria defined in the specifications, the budget requirements, and the predefined schedule. The systems contractors’ responsibilities are to furnish and install a fully functional system that meets the design specifications. There are generally several contractors whose work must be coordinated to ensure that the end product is a cohesive system.

Once the commissioning team is in place, commissioning can take place, and it occurs in defined and delineated phases—the subject of the following section.

COMMISSIONING PHASES

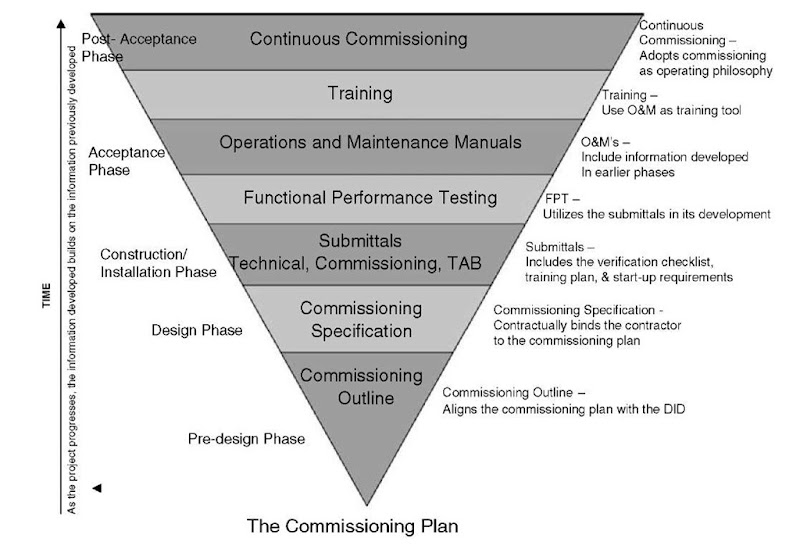

The commissioning process occurs over a variety of clearly delineated phases. The commission plan is the set of documents and events that defines the commissioning process over all phases. The commissioning plan needs to reflect a systematic, proactive approach that facilitates communication and cooperation of the entire design and construction team.

The phases of the commissioning process are:

Predesign

Design

Construction/installation

Acceptance

Postacceptance

These phases and the commissioning activities associated with them are described in the following sections.

Predesign Phase

The predesign phase is the phase in which the design intent is established in the form of the DID. In this phase of a construction project, the role of commissioning in the project is established if process-based commissioning is followed. Initiation of the commissioning process in the predesign phase increases acceptance of the commissioning process by all design team members. Predesign discussions about commissioning allow all team members involved in the project to assess and accept the importance of commissioning to a successful project. In addition, these discussions give team members more time to assimilate the impact of commissioning on their individual roles and responsibilities in the project. A successful project is more likely to result when the predesign phase is built around the concept of commissioning instead of commissioning’s being imposed on a project after it has been designed.

Once an owner has decided to adopt commissioning as an integral part of the design and construction of a project, the owner should be urged to follow the LEED certification process, as discussed above. The commissioning agent can assist in the documentation preparation required for the LEED certification, which occurs in the postacceptance phase.

The predesign phase is the ideal time for an owner to select and retain the commissioning agent. The design team member should, if possible, be involved in the selection of the commissioning agent because that member’s involvement will typically ensure a more cohesive commissioning team. Once the commissioning agent is selected and retained, the commissioning-approach outline is developed. The commissioning-approach outline defines the scope and depth of the commissioning process to be employed for the project. Critical commissioning questions are addressed in this outline. The outline will include, for most projects, answers to the following questions:

What equipment is to be included?

What procedures are to be followed?

What is the budget for the process?

As the above questions suggest, the commissioning budget is developed from the choices made in this phase. Also, if the owner has a commissioning policy, it needs to be applied to the specifics of the particular project in this phase.

The key event in the predesign phase is the creation of the DID, which defines the technical criteria for meeting the requirements of the intended use of the facilities. The DID document is often created based in part upon the information received from interviews with the intended building occupants and maintenance staff. Critical information—such as the hours of operation, occupancy levels, special environmental considerations (such as pressure and humidity), applicable codes, and budgetary considerations and limitations—is identified in this document. The owner’s preference, if any, for certain equipment or contactors should also be identified at this time. Together, the answers to the critical questions above and the information in the DID are used to develop the commissioning approach outline. A thorough review of the DID by the commissioning agent ensures that the commissioning-approach outline will be aligned with the design intent.

With the commissioning agent selected, the DID document created, and the commissioning approach outline in place, the design phase is ready to commence.

Design Phase

The design phase is the phase in which the schematics and specifications for all components of a project are prepared.

One key schematic and set of specifications relevant to the commissioning plan is the MEP schematic design, which specifies installation requirements for the MEP systems. As noted, the DID is the basis for creating the commissioning approach outline in the predesign phase. The DID also serves as the basis for creating the MEP schematic design in the design phase. The DID provides the MEP designer with the key concepts from which the MEP schematic design is developed.

The completed MEP schematic design is reviewed by the commissioning agent for completeness and conformance to the DID. At this stage, the commissioning agent and the other design team members should consider what current technologies, particularly those for energy efficiency, could be profitably included in the design. Many of the design enhancements currently incorporated into existing buildings during energy retrofitting for operational optimization are often not considered in new building construction. This can result in significant lost opportunity, so these design enhancements should be reviewed for incorporation into the base design during this phase of the commissioning process. This point illustrates the important principle that technologies important to retrocommissioning should be applied to new building construction—a point that is surprisingly often overlooked in the industry today.

For example, the following design improvements and technologies should always be considered for applicability to a particular project:

• Variable-speed fan and pumps installed

• Chilled water cooling (instead of DX cooling)

• Utility meters for gas, electric, hot water, chilled water, and steam at both the building and system level

• CO2 implementation for minimum indoor air requirements

This list of design improvements is not exhaustive; the skilled commissioning agent will create and expand personalized lists as experience warrants and as the demands of particular projects suggest.

In addition to assisting in the evaluation of potential design improvements, the commissioning agent further inspects the MEP schematic design for:

• Proper sizing of equipment capacities

• Clearly defined and optimized operating sequences

• Equipment accessibility for ease of servicing

Once the commissioning agent’s review is complete, the feedback is discussed with the design team to determine whether its incorporation into the MEP schematic design is warranted. The agreed-upon changes or enhancements are incorporated, thus completing the MEP schematic design.

The completed MEP schematic design serves as the basis on which the commissioning agent will transform the commissioning-approach outline into the commissioning specification.

The commissioning specification is the mechanism for binding contractually the contractors to the commissioning process. Expectations are clearly defined, including:

• Responsibilities of each contractor

• Site meeting requirements

• List of the equipment, systems, and interfaces

• Preliminary verification checklists

• Preliminary functional-performance testing checklists

• Training requirements and who is to participate

• Documentation requirements

• Postconstruction documentation requirements

• Commissioning schedule

• Definition for system acceptance

• Impact of failed results

Completion of the commissioning specification is required to select the systems contractor in a competitive solicitation. Alternatively, however, owners with strong, preexisting relationships with systems contractors may enter into a negotiated bid with those contractors, who can then be instrumental in finalizing the commissioning specification.

Owners frequently select systems contractors early in the design cycle to ensure that the contractors are involved in the design process. As noted above, if there are strong, preexisting relationships with systems contractors, early selection without a competitive selection process (described in the following paragraph) can be very beneficial. However, if there is no competitive selection process, steps should be taken to ensure that the owner gets the best value. For example, unit pricing should be negotiated in advance to ensure that the owner is getting fair and reasonable pricing. The commissioning agent and the MEP designer can be good sources for validating the unit pricing. The final contract price should be justified with the unit pricing information.

If the system selection process is competitive, technical proposals should be requested with the submission of the bid price. The systems contractors need to demonstrate a complete understanding of the project requirements to ensure that major components have not been overlooked. Information such as the project schedule and manpower loading for the project provide a good basis from which to measure the contractor’s level of understanding. If the solicitation does not have a preselected list of contractors, the technical proposal should include the contractor’s financial information, capabilities, and reference lists. As in the negotiated process described above, unit pricing should be requested to ensure the proper pricing of project additions and deletions. The review of the technical proposals should be included in the commissioning agent’s scope of work.

A mandatory prebid conference should be held to walk the potential contractors through the requirements and to reinforce expectations. This conference should be held regardless of the approach—negotiated or competitive— used for contractor selection. The contractor who is to bear the financial burden for failed verification tests and subsequent functional-performance tests should be reminded of these responsibilities to reinforce their importance in the prebid meeting. The prebid conference sets the tone of the project and emphasizes the importance of the commissioning process to a successful project.

Once the MEP schematic design and commissioning specification are complete, and the systems contractors have been selected, the construction/installation phase begins.

Construction/Installation Phase

Coordination, communication, and cooperation are the keys to success in the construction and installation phase. The commissioning agent is the catalyst for ensuring that these critical activities occur throughout the construction and installation phase.

Frequently, value engineering options are proposed by the contractors prior to commencing the installation. The commissioning agent should be actively involved in the assessment of any options proposed. Many times, what appears to be a good idea in construction can have a disastrous effect on a facility’s long-term operation. For example, automatic controls are often value engineered out of the design, yet the cost of their inclusion is incurred many times over in the labor required to perform their function manually over the life of the building. The commissioning agent can ensure that the design intent is preserved, the life-cycle costs are considered, and the impact on all systems of any value engineering modification proposed is thoroughly evaluated.

Once the design aspects are complete and value engineering ideas have been incorporated or rejected, the submittals, including verification checklists, need to be finalized. The submittals documentation is prepared by the systems contractors and reviewed by the commissioning agent. There are two types of submittals: technical submittals and commissioning submittals. Both types of submittals are discussed below.

Technical submittals are provided to document the systems contractors’ interpretation of the design documents. The commissioning agent reviews the technical submittals for compliance and completeness. It is in this submittal review process that potential issues are identified prior to installation, reducing the need for rework and minimizing schedule delays. The technical submittals should include:

• Detailed schematics

• Equipment data sheets

• Sequence of operation

• Bill of material

A key technical submittal is the testing, adjusting, and balancing submittal (TAB). The TAB should include:

• TAB procedures

• Instrumentation

• Format for results

• Data sheets with equipment design parameters

• Operational readiness requirements

• Schedule

In addition to the TAB, other technical submittals, such as building automation control submittals, will be obtained from the systems contractors and reviewed by the commissioning agent.

The commissioning submittal generally follows the technical submittal in time and includes:

• Verification checklists

• Startup requirements

• Test and balance plan

• Training plan

The commissioning information in the commissioning submittal is customized for each element of the system.

These submittals, together with the commissioning specification, are incorporated into the commissioning plan, which becomes a living document codifying the results of the construction commissioning activities. This plan should be inspected in regular site meetings. Emphasis on the documentation aspect of the commissioning process early in the construction phase increases the contractors’ awareness of the importance of commissioning to a successful project.

In addition to the submittals, the contractors are responsible for updating the design documents with submitted and approved equipment data and field changes on an ongoing basis. This update design document should be utilized during the testing and acceptance phase.

The commissioning agent also performs periodic site visits during the installation to observe the quality of workmanship and compliance with the specifications. Observed deficiencies should be discussed with the contractor and documented to ensure future compliance. Further inspections should be conducted to ensure that appropriate corrective action has been taken.

The best way to ensure that the items discussed above are addressed in a timely manner is to hold regularly scheduled commissioning meetings that require the participation of all systems contractors. This is the mechanism for ensuring that communication occurs. Meeting minutes prepared by the commissioning agent document the discussions and decisions reached. Commissioning meetings should be coordinated with the regular project meetings because many participants in a construction project need to attend both meetings.

Typical elements of a commissioning meeting include:

• Discussing field installation issues to facilitate rapid response to field questions

• Updating design documents with field changes

• Reviewing the commissioning agent’s field observations

• Reviewing progress against schedule

• Coordinating multicontractor activities

Once familiar with the meeting process, an agenda will be helpful but not necessary. Meeting minutes should be kept and distributed to all participants.

With approved technical and commissioning plan submittals, as installation progresses, the contractor is ready to begin the system verification testing. The systems contractor generally executes the system verification independently of the commissioning agent. Contractor system verification includes:

• Point-to-point wiring checked out

• Sensor accuracy validated

• Control loops exercised

Each of the activities should be documented for each control or system element, and signed and dated by the verification technician.

The documentation expected from these activities should be clearly defined in the commissioning specification to ensure its availability to the commissioning agent for inspection of the verification process. The commissioning agent’s role in the system verification testing is to ensure that the tests are completed and that the results reflect that the system is ready for the functional-performance tests. Because the commissioning agent is typically not present during the verification testing, the documentation controls how successfully the commissioning agent performs this aspect of commissioning.

In addition to system verification testing, equipment startup is an important activity during this phase. Equipment startup occurs at different time frames relative to the system verification testing, depending on the equipment and system involved. There may be instances when the system verification needs to occur prior to equipment startup to prevent a catastrophic event that could lead to equipment failure. The commissioning agent reviews the startup procedures prior to the startup to ensure that equipment startup is coordinated properly with the system verification. Unlike in verification testing, the commissioning agent should be present during HVAC equipment startup to document the results. These results are memorialized in the final commissioning report, so their documentation ultimately is the responsibility of the commissioning agent.

Once system verification testing and equipment startup have been completed, the acceptance phase begins.

Acceptance Phase

The acceptance phase of the project is the phase in which the owner accepts the project as complete and delivered in accordance with the specifications, and concludes with acceptance of the project in its entirety. An effective commissioning process during the installation phase should reduce the time and labor associated with the functional-performance tests of the acceptance phase.

Statistical sampling is often used instead of 100% functional-performance testing to make the process more efficient. A 20% random sample with a failure rate less than 1% indicates that the entire system was properly installed. If the failure rate exceeds 1%, a complete testing of every system may need to be completed to correct inadequacies in the initial checkout and verification testing. This random-sampling statistical approach holds the contractor accountable for the initial checkout and test, with the performance testing serving only to confirm the quality and thoroughness of the installation. This approach saves time and money for all involved. It is critical, however, that the ramifications of not meeting the desired results of the random tests are clearly defined in the commissioning specifications.

The commissioning agent witnesses and documents the results of the functional-performance tests, using specific forms and procedures developed for the system being tested. These forms are created with the input of the contractor in the installation phase. Involvement of the maintenance staff in the functional-performance testing is important. The maintenance team is often not included in the design process, so they may not fully understand the design intent. The functional-performance testing can provide the maintenance team an opportunity to learn and appreciate the design intent. If the design intent is to be preserved, the maintenance team must fully understand the design intent. This involvement of the maintenance team increases their knowledge of the system going into the training and will increase the effectiveness of the training.

Training of the maintenance team is critical to a successful operational handover once a facility is ready for occupancy. This training should include:

• Operations and maintenance (O&M) manual overview

• Hardware component review

• Software component review

• Operations review

• Interdependencies discussion

• Limitations discussion

• Maintenance review

• Troubleshooting procedures review

• Emergency shutdown procedures review

The support level purchased from the systems contractor determines the areas of most importance in the training and therefore should be determined prior to the training process. Training should be videotaped for later use by new maintenance team members and in refresher courses, and for general reference by the existing maintenance team. Using the O&M manuals as a training manual increases the maintenance team’s awareness of the information contained in them, making the O&M manuals more likely to be referenced when appropriate in the future.

The O&M manuals should be prepared by the contractor in an organized and easy-to-use manner. The commissioning agent is sometimes engaged to organize them all into an easily referenced set of documents. The manuals should be provided in both hard-copy and electronic formats, and should include:

• System diagrams

• Input/output lists

• Sequence of operations

• Alarm points list

• Trend points list

• Testing documentation

• Emergency procedures

These services—including functional-performance testing, training, and preparing O&M manuals—should be included in the commissioning plan to ensure the project’s successful acceptance. The long-term success of the project, however, is determined by the activities that occur in the post acceptance phase.

Post acceptance Phase

The post acceptance phase is the phase in which the owner takes beneficial occupancy and forms an opinion about future work with the design team, contractors, and the commissioning agent who completed the project. This is also the phase in which LEED certification, if adopted, is completed. Activities that usually occur in the acceptance phase should instead occur in the post acceptance phase. This is due to constraints that are not controllable by the contractor or owner. For example, seasonal changes may make functional-performance testing of some HVAC systems impractical during the acceptance phase for certain load conditions. This generally means that in locations that experience significant seasonal climate change, some of the functional-performance testing is deferred until suitable weather conditions exist. The commissioning agent determines which functional-performance tests need to be deferred and hence carried out in the post acceptance phase.

During the post acceptance phase, the commissioning agent prepares a final commissioning report that is provided to the owner and design team. The executive summary of this report provides an overall assessment of the design intent conformance. The report details whether the commissioned equipment and systems meet the commissioning requirements. Problems encountered and corrective actions taken are documented in this report. The report also includes the signed and dated startup and functional-performance testing checklists.

The final commissioning report can be used profitably as the basis of a “lessons learned” meeting involving the design team so that the commissioning process can be continuously improved and adaptations can be made to the owner’s commissioning policy for future projects. The owner should use the experience of the first commissioned project to develop the protocols and standards for future projects. The documentation of this experience is the owner’s commissioning policy. Providing this policy and the information it contains to the design and construction team for the next project can help the owner reduce budget overruns by eliminating any need to reinvent protocols and standards and by setting the right expectations earlier in the process.

Commissioning therefore should not be viewed as a one-time event but should instead be viewed as an operational philosophy. A recommissioning or continuous commissioning plan should be adopted for any building to sustain the benefits delivered from a commissioning plan. The commissioning agent can add great value to the creation of the recommissioning plan and can do so most effectively in the post acceptance phase of the project.

Fig. 1 depicts the information development that occurs in the evolution of a commissioning plan and summarizes the information presented in the preceding sections by outlining the various phases of the commissioning process.

With this background, the reader is better positioned for success in future commissioning projects and better prepared to learn the key success factors in commissioning and how to avoid common mistakes in the commissioning process.

COMMISSIONING SUCCESS FACTORS

Ultimately, the owner will be the sole judge of whether a commissioning process has been successful. Thus, second only to the need for a competent, professional commissioning agent, keeping the owner or the owner’s senior representative actively involved in and informed at all steps of the commissioning process is a key success factor. The commissioning agent should report directly to the owner or the owner’s most senior representative on the project, not only to ensure that this involvement and information transfer occur, but also to ensure the objective implementation of the commissioning plan—a third key success factor.

Another key success factor is an owner appreciation— which can be enhanced by the commissioning agent—that commissioning must be an ongoing process to get full benefit. For example, major systems should undergo periodic modified functional testing to ensure that the original design intent is being maintained or to make system modification if the design intent has changed. If an owner appreciates that commissioning is a continuous process that lasts for the entire life of the facility, the commissioning process will be a success.

Fig. 1 The commissioning plan.

Most owners will agree that the commissioning process is successful if success can be measured in a cost/benefit analysis. Cost/benefit or return on equity is the most widely used approach to judge the success of any project. Unfortunately, the misapplication of cost/benefit analyses has been the single largest barrier to the widespread adoption of commissioning. For example, because new construction does not have an energy baseline from which to judge energy savings, improper application of a cost/ benefit analysis can lead to failure to include energy savings technologies—technologies the commissioning agent can identify—in the construction process. Similarly, unless one can appreciate how commissioning can prevent schedule delays and rework by spotting issues and resolving them early in the construction process, one cannot properly offset the costs of commissioning with the benefits.

Fortunately, there are now extensive studies analyzing the cost/benefit of commissioning that justify its application. A study performed jointly by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; Portland Energy Conservation, Inc.; and the Energy Systems Laboratory at Texas A&M

University provides compelling analytical data on the cost/benefit of commissioning. The study defines the median commissioning cost for new construction as $1 per square foot or 0.6% of the total construction cost. The median simple payback for new construction projects utilizing commissioning is 4.8 years. This simple payback calculation does not take into account the quantified nonenergy impacts, such as the reduction in the cost and frequency of change orders or premature equipment failure due to improper installation practices. The study quantifies the median nonenergy benefits for new construction at $1.24 per square foot per year.[3]

While the primary cost component of assessing the cost/benefit of commissioning lies in whether there was a successful negotiation of the cost of services with the commissioning service provider, the more important aspect of the analysis relates to the outcomes of the process. For example, after a commissioning process is complete, what are the answers to these questions?

Are the systems functioning to the design intent? Has the owner’s staff been trained to operate the facility?

How many of the systems are operated manually a year after installation?

Positive answers to these and similar questions will ensure that any cost/benefit analysis will demonstrate the value of commissioning.

To ensure that a commissioning process is successful, one must avoid common mistakes. A commissioning plan is a customized approach to ensuring that all the systems operate in the most effective and efficient manner. A poor commissioning plan will deliver poor results. A common mistake is to use an existing commissioning plan and simply insert it into a specification to address commissioning. Each commissioning plan should be specifically tailored to the project to be commissioned.

Also, perhaps due to ill-conceived budget constraints, commissioning is implemented only in the construction phase. Such constraints are ill conceived because the cost of early involvement of the commissioning agent in the design phases is insignificant compared with the cost of correcting design defects in the construction phase. Significant cost savings can arise from identifying design issues prior to construction. Studies have shown that 80% of the cost of commissioning occurs in the construction phase.[2] Also, the later the commissioning process starts, the more confrontational commissioning becomes, making it more expensive to implement later in the process.[2] Therefore, adopting commissioning early in the project is a key success factor.

Value engineering often results in ill-informed, last-minute design changes that have an adverse and unintended impact on the overall building performance and energy use.[3] By ensuring that the commissioning process includes careful evaluation of all value engineering proposals, the commissioning agent and owner can avoid such costly mistakes.

Finally, the commissioning agent’s incentive structure should not be tied to the number of issues brought to light during the commissioning process, as this can create an antagonistic environment that may create more problems than it solves. Instead, the incentive structure should be outcome based and the questions outlined above regarding compliance with design intent, training results, and post acceptance performance provide excellent bases for a positive incentive structure.

— Improved quality of construction

• Reduced facility life-cycle cost

— Reduced impact of design changes

— Fewer change orders

— Fewer project delays

— Less rework or post construction corrective work

— Reduced energy costs

• Increased occupant satisfaction

— Shortened turnover transition period

— Improved system operation

— Improved system reliability

With these benefits, owners and contractors alike should adopt the commissioning process as the best way to ensure cost-efficient construction and the surest way to a successful construction project.

CONCLUSION

Commissioning should be performed on all but the most simplistic of new construction projects. The benefits of commissioning include:

• Optimization of building performance

— Enhanced operation of building systems

— Better-prepared maintenance staff

— Comprehensive documentation of systems

— Increased energy efficiency