introduction

One of the most challenging issues facing educators in all levels of formal schooling, particularly higher education, is assessment of complex learning outcomes of what is called “21st century skills” (Bennett, Persky, Weissm, & Jenkins (NAEP), 2007). Faculty, administrators, students, parents, and the public at large are increasingly concerned about how assessment is conducted in higher education (Reeves, 2000). Scholars have also questioned current approaches to assessing institutional quality (Callan & Finney, 2002; Ewell, 2002), indicating assessing student learning should be the fundamental purpose of higher education. Over the years, various types of assessment models have been developed. The newer assessment models address complex learning outcomes and support measuring learning more authentically and providing alternatives to the conventional, test-based assessment models (Glaser & Silver, 1994; Resnick & Resnick, 1992; Sanders, 2001). Alternative assessment models and methods promise to promote authentic, real world learning, and to provide a diversity of learning opportunities so students are able to display critical thinking skills and greater depth of knowledge, connect learning to their daily lives, develop a deeper dialog over the course material, and foster both individual and group oriented learning activities (Muirhead, 2002). Furthermore, alternative, authentic assessment models support assessment for learning rather than assessment for grading (Black & William, 1998). The concept of assessment for learning, emphasizes integrating assessment and instruction and requires a dynamic, continuous, and performance-based assessment system that emphasizes progress in learning (formative assessment) and in becoming increasingly sophisticated learners and knowers. Ideally, performances that are based on real-life activities become an integral part of the instructional cycle, and feedback provided by the teacher and peers is meant to be formative, that is, it is intended to help the student assess his or her strengths and weaknesses, identifying areas of needed growth and mobilizing current capacity. These performances are provocations for what needs to be learned and extensions of what is learned and can help push the student to the next level of skill in performance (NCREL, 1990; NAEP, 2007). The premises of performance-based assessment models, particularly their emphasis on pedagogical changes in teaching methods and in educational philosophy, continue to challenge educators in higher education and to call for radical reformulation of the basic assumptions of education and the role of assessment.

The emergence of distance education in the form of online or Web-based delivery has taken this challenge further and has added to its complexity and its ambiguity. Numerous studies over the past few years have sought to affirm that distance education is equally as effective (if not better) as face-to-face learning. Many studies have shown that there is no significant difference in the learning outcomes that occur in a distance environment versus face-to-face (e.g., Allen, Bourhis, Burrell, & Mabry, 2002; Bernard, Abrami, Lou, Borokhovski, Wade, Wozney, Wallet, Fiset, & Huang, 2004; Shachar & Neumann, 2003). While this may be so, there is not enough information about what is assessed in online courses compared with on site courses, and whether or not a full range of assessment strategies were compared. In other words, it is not clear if online instructors are using the full potential of online learning for assessment purposes to suggest that there is no difference in student learning in a distance environment compared to face-to-face.

This article analyzes the problem or performance-based approach for assessing complex learning outcomes. It also explores the potential of online learning environments for implementing a problem/performance-based assessment system and proposes a design framework for applying such a system in an online learning environment. Finally, the article shares some thoughts on future trends and issues in assessment of complex learning outcomes.

problem-based, performance-based, assessment

Conventional or traditional assessment practices in higher education often refer to paper-and-pencil activities. Typically, students are asked to write a few short papers or one large research based paper and to take a mid term and final examination. Exams often consist of short answer questions (multiple-choice, true-false, fill-in-the -blank, matching) and/or short essays. Traditionally, instructors write comments on tests, papers and project. These comments range from clarifying the quality of student performance to making suggestions for improvement. Given that these comments are often provided when students have completed the work and submitted it for a grade (summative judgment) it is left up to the student to decide whether he/she wants to improve the work. Therefore, the instructor’s comments may or may not serve as guidelines, compromising the value of writing comments at all. While traditional assessment practices may have their own advantages, they often measure discrete, isolated skills and do not promote complex knowledge and skills, such as critical thinking and active construction of meaning.

On the other hand, performance/problem-based assessment requires demonstration of not only what students know, but also what students can do (Hibbard, Shaw, Van Wagenen, Lewbet, & Waterbury-Wyatt, 1996). Performance/Problem-based assessment emphasizes application and use of knowledge and includes holistic performance of meaningful, complex tasks in challenging real-world environments. Authentic, real world tasks or activities are often multidimensional and require higher order thinking and problem solving skills. In addition, performance/problem-based assessment involves examination of process, as well as product of learning. Progress in both process and product is measured by continuous monitoring of performance over time. Several characteristics differentiate complex or problem-based and/or performance-based assessment from traditional forms of assessment, and may include the following:

• Assessment is focused on measuring complex learning outcomes such as higher level learning in the form of problem solving skills.

• Assessment task is presented within a meaningful context (Meyer, 1992; Reeves & Okey, 1996; Wiggins, 1993).

• Assessment task provides complex, ill structured challenges that require judgment and a full array of tasks (Wiggins, 1990; 1993; Linn, Baker, & Dunbar, 1991; Torrance, 1995).

• Assessment task requires significant student time and effort in collaboration with others (Linn, Baker, & Dunbar, 1991; Kroll, Masingila, & Mau, 1992).

• Assessment is seamlessly integrated with learning task or activity.

• Assessment task provides multiple indicators of learning (Wiggins, 1990; Lajoie, 1991; Resnick & Resnick, 1992).

assessment of complex learning in technology rich, online learning environments

An examination of the literature on online learning indicates that the online learning environment has the highest potential for complex and real world, authentic performance assessment (e.g., Hazari & Schorr, 1999; Nelson, 1998; Wild & Omari, 1996). The literature suggests that new technology tools and resources that are available in an online learning environment make implementation of a complex or performance/problem-based, project-based, progress-based assessment model a reality. Furthermore, review of the available course management systems (e.g., BlackboardVista, Sakai, Moodle) for online delivery ofinstruction suggests that there are tools and resources within this technology that are not readily available in face-to-face courses. Such tools and resources provide an easier and more effective system to conduct problem-based assessment because of the emphasis on interactive, formative and continuous assessment. Some of these tools and resources are as follows:

• The database and interactive system to track, monitor and document students’ activities automatically.

• Easy access and easy development process for conventional assessment tools (quizzes, open-ended question, etc.) to give students the opportunity to self-assess their own knowledge through automatic and instant feedback.

• Multiple social and communication tools (synchronous, asynchronous) to facilitate as well as to document dialogue between and among learners, materials and the instructor.

• Content tools to develop and manage multimedia rich projects and problem solving tasks that incorporate multiple resources and perspectives and require collaboration and learners’ interaction and engagement.

• Content tools to make it possible for learners to complete the complex tasks at various intervals to track the progress.

• Communication and content tools to provide continuous formal and informal feedback on assignments, thoughts and progress from both the instructor and peers and other mentors or colleagues.

• Unlimited and self-paced access to course materials and communication tools to complete independent and team work projects/problems at any time.

• Interactive, but asynchronous communication tools, to promote thoughtful and reflective commentaries.

• Both learner’s and instructor’s access to the record of responses, answers, feedback, etc. to analyze and interpret one’s own performance and to reflect.

In addition to the availability of the above-mentioned assessment tools and resources in the majority of current online course management systems, learners and instructors can use various emerging, yet open-source technology tools, to complete a project or to solve a problem even though the tools may not have yet been integrated in the adopted course management system. Furthermore, the online teaching and learning provides an excellent environment for practicing duties of a mentor, coach and/or facilitator that are necessary for developing critical thinking and problem solving skills. Given automatic documentation of student work and thoughts and easy access to such documents and records, providing proper guidance and feedback are not as difficult as it is in traditional face-to-face classrooms.

a model for assessing complex learning outcomes in online learning

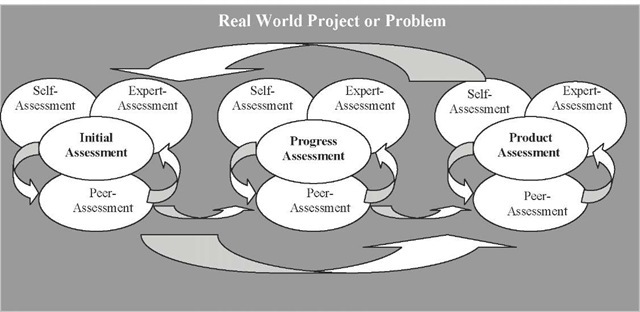

Figure 1 shows the conceptualization of performance-based assessment in an online learning environment. As Figure 1 shows, a challenging, complex and authentic task, problem, or investigation is the main focus of assessment of student learning. Such a task measures complex learning outcomes and bears a close relationship to real world problems in the home and workplace of today and tomorrow and involves sustained amounts of time to be completed. This larger and more ambitious project/task/problem is divided into smaller problems/projects that prepare students for the larger and more complex tasks. The assessment of tasks, projects or problems is integrated in instruction and occurs throughout the instruction. However, as Figure 1 shows, three forms or stages of assessment can coexist for each task regardless of their complexity in an online learning environment; and they include initial assessment, progress assessment, and product assessment. While each stage or form of assessment would have different purposes, the process and results of each assessment stage should affect other stages directly. In all stages of assessment, students take responsibility and are involved in setting and using standards of excellence to evaluate whether they have achieved their goals. In addition, in each stage of assessment, the teacher/expert models thinking processes and strategies, and monitors individual students as they work on instructional tasks in order to assess thinking processes and provide ongoing feedback. Projects and other instructional tasks are designed to be completed by groups, and students are encouraged to, not only share ideas and resources, but also to assess each other’s work. Thus, for each instructional task, three different, but related, assessment tools are used: self-assessment, expert assessment and peer assessment. During all stages of assessment, the feedback provided by the teacher and peers is meant to be formative- that is, it is intended to help the student assess his or her strengths and weaknesses, identify areas of needed growth and mobilize current capacity. Performances are provocations for what needs to be learned, and extensions of what is learned can help push the student to the next level of skill in performance. Performances also become tools for reflection on learning accomplished and learning deferred.

Figure 1. The conceptual model for performance-based assessment in an online learning environment

THE STAGES OF THE MODEL

The initial assessment stage provides both public and private computerized individual assessment activities in which individual learners test their current knowledge constructions and understanding before having to work with groups or go public with their ideas. During this stage the teacher/expert reviews the student’s initial thoughts and provides individual and private feedback to foster further thinking and reflection. After self-reflection and self-assessment of initial thoughts, the learner goes public by sharing his/her ideas with peers or group members. This initial sharing of ideas provides an opportunity for the student to benefit from peers’ perspectives. By focusing attention on the contrast between what the student has generated and what other peers think of the product, the student then engages in more self-assessment and may begin noticing important distinctions among different perspectives and accommodating new ideas (Schwartz & Bransford, 1998).

During the stage of progress assessment, students work as teams to share and discuss ideas, use different technology tools to test ideas and form hypotheses, consult resources, listen and read “just-in-time” lectures and expert opinions and explore ways to solve the problem in hand. The teacher/expert’s role is to monitor closely both teams’ discussion and individual student contributions in order to provide new resources or redirect students to the existing resources, offer “just-in-time” lectures or skill building lessons, ask guiding questions, and help students test their thoughts or solution using self-assessment rubrics or criteria. During this stage the three forms of assessment—self-assessment, peer-assessment, and expert assessment– may occur all at the same time. As a result of working with teams, which involves peer-discussion and peer-assessment, individual students may engage in self-assessment of their own thoughts and ideas. They may realize the needs for seeking more information, exploring extra resources, and mastering areas of knowledge and skills that are lacking. The expert’s continuous assessment of the team’s progress toward their goals should provide a different level of assessment for both teams and individual students. Therefore, the combination of self-assessment, peer-assessment and expert assessment during the process of solving problems should help students to progress in their thinking and in solving the bigger problem or project.

The last stage of assessment—product assessment— occurs at three levels. Individual students and teams should use both the standards and criteria for the best product and the model performance to conduct a self-assessment of their own products and identify the areas of improvement before submitting the final product. Teams or groups may serve as peer-reviewers of each other’s products and provide constructive feedback. Expert’s periodic review of students’ products should also provide formative information about the quality of the final product. As a result of this multiple level of formative assessment, the quality of students’ final products should be assured. The summative evaluation of students’ products should serve as a means of both evaluating achievements of goals and the effectiveness of instruction.

toolkit for assessing complex learning in online learning environments

Implementation of the above-described model requires development of a series of learning and/or assessment tools. The following explains these tools:

• Design and development of a simulated or multimedia rich real world performance task or problem: A real world project or problem that requires students to demonstrate achievement of a set of complex learning outcomes should be developed. The real world task could be a simulated scenario that would feature as much as possible the exploration characteristic of real-world problem solving. In other words, the task or problem should be multifaceted and require students to engage in activities which present the same type of cognitive challenges as those in the real world (Honebein, Duffy, & Fishman, 1993). The real world task will serve as a learning activity as well as an assessment tool.

• Design and development of simpler performance tasks and problems: The complexity of the main task, project or problem and its relatively long-term integrated units of instruction should make it possible to break the task into several subtasks or mini projects, tasks or problems to be completed at various intervals. The less complex but related subordinate tasks or problems should provide the required learning experiences for the completion of the main task, project or problem. The subtasks should be designed to be real world problems, yet address domain specific knowledge and skills that students need in order to complete the main task. Upon development of these subtasks, each subtask or problem can be analyzed to further identify technology tools needed and develop resources and supporting instructional materials. The subtasks should also provide some structure and serve as a timeline for student work as well as to incorporate process-based, continuous assessment and feedback.

• Clear list of assessment criteria for the main performance task and subtasks: After the main task and its subtasks are determined, the elements within each task that can be used to determine the success of the student’s performance should be identified and developed into a list of assessment criteria or rubric. Assessment criteria are designed to be either product related, for example, a lab report on a photosynthesis experiment; content specific, for example, a research project on Japanese American relocation camps; or task specific, for example, writing an essay with a thesis statement. Often students are encouraged to participate in this process. A clearly defined list of criteria will make it easier for learners and the instructor to remain objective during the learning and assessment process. Moreover, the assessment criteria can serve as a self-assessment tool as well as guidance for offering feedback for improvement.

• Examples of model performance: For the main task and each of the subtasks examples of desired performance (completed by a skilled (but not an expert), a performer should be selected and made available (Jonassen, 1999). Worked or model examples should include a description of how the problems are solved by an experienced problem solver (Sweller & Cooper, 1985). Worked examples can serve as an assessment tool to communicate task or problem requirements as well as understanding the nature of the problem.

• Non-graded, self-assessment quizzes: For each subtask, or domain specific knowledge and skills, non-graded, self-assessment quizzes should be developed. These non-graded, self-assessment quizzes should provide immediate feedback using automatic computerized feedback and encourage students to self-assess their own understanding of the learning materials before engaging in discussion with their collaborative team.

• Guideline and assessment rubric for collaboration and team work: In order to establish individual accountability toward the group task, to encourage commitment to the group and its goals and encourage efforts toward achieving the group goals and to facilitate smooth interaction among group members both at an interpersonal and/or a group level (a set of guidelines should be developed. These guidelines then should be used to develop a rubric to assess collaboration and group work. Both instructor/facilitator and peers should participate in assessing collaboration and team work skills.

• Individual thinking and reflective assignments: Within each domain specific task individual learners should be directed to engage in assessing their own prior knowledge related to each task or problem and in formulating their initial thoughts before working in groups and on the task. To accomplish this goal, a set of thinking and reflective questions should be developed to encourage individual learners to respond to these questions to activate their prior knowledge and to make their implicit thoughts explicit. Learners’ responses to these questions can be responded to by a new set of reflective thoughts and questions. Blogs and wikis should be used to, not only provide the environment, but also to track and monitor learners’ thoughts.

• Collaborative peer evaluation checklists: Peer evaluation can be a useful and valuable tool in helping students to develop their critical skills and insight into the evaluation process. By making a critical appraisal of another student’s work or performance, students can begin to understand the requirements of the curriculum and the teacher. Furthermore, an effective and increasingly common way of addressing individual accountability to the team is to have team members rate one another’s performance and to use the ratings to improve the team assignment to adjust for individual performance.

The challenge is to devise a peer review rating system that is fair, simple to administer, reliable, and valid. To effectively implement peer evaluation two rubrics or rating sheets should be developed. The first rubric is for the students to use in doing their reviews, and the second is for instructors to use in doing their reviews of reviews.

ISSUES INFLUENCE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE MODEL

Several issues may hinder the successful implementation of this model in the online learning environment.

First, in order to fully implement a process-based, performance-based assessment system in an online learning environment, the instructor/facilitator of the course must be willingly accessible and fully responsive to student ideas, views and changes. Second, applying a performance-based assessment system requires the instructor’s/facilitator’s epistemological beliefs in learning as a personal construction of meaning and assessment as a contextual, longitudinal and collaborative process between students and teachers. Such beliefs would further facilitate the integration of assessment and instruction and would encourage students to analyze, interpret, and predict information and engage in self-reflection. Thus, in the absence of such a philosophy of learning and assessment, it is difficult to implement a model of assessment that demands a new way of thinking about learning and assessment. Third, a successful implementation of this assessment model requires a manageable number of online learners (small class size), or in the case of large scale courses, an employment of multiple, well trained and capable facilitators to monitor student progress and to provide just-in time guidance. Fourth, establishment of a participatory online learning environment is crucial for implementation of this model. Finally, designing, developing, and particularly delivering an online course that incorporates performance-based, process and product-based assessment system requires considerable time and effort both on the part of the instructor and students. Students of such courses must be willing to achieve higher performance standards, and to that end must be willing to spend time and effort to use assessment tools to monitor their own progress and to promote their own understanding.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE TRENDS

Clearly, assessment of complex learning outcomes will need more sophisticated instruments than constructing a test and an answer key. In addition, implementing such a complex assessment system requires advanced and more sophisticated technology tools. A discussion of these issues can be found in “The efficacy of current technology tools for assessment of complex learning outcomes in online learning environments” in this issue for the interested readers. In this section, the trends and issues for the proposed assessment system and its instrumentations will be discussed.

In order to make reliable judgments, high quality performance criteria are needed. These assessment criteria or rubrics should be developed from the standards and benchmarks adopted in each course or subject area. However, developing a clear and an effective rubric (rating scale with several categories) for judging students’ process of learning and products is harder than carrying out the activity. Thus, a skillful teacher/designer is needed to develop the assessment criteria and rubrics and then to carry out an assessment system that is embedded in day to day instructional activities. If a teacher fails to have a clear sense of the full dimensions of performance, ranging from poor or unacceptable to exemplary, he or she will not be able to teach students to perform at the highest levels or help students to evaluate their own performance. Future efforts, therefore, should be devoted to assisting online teachers/designers to understand the characteristics of a task’s design that facilitates the requirements of an entire course of study and where the students make the important decisions about why, how, and in what order they investigate a problem. To develop and implement an assessment system that focuses on complex learning outcomes, teachers/designers should be clear on the relationship that exists between the learners, tasks, and technology engaged in authentic learning settings. In other words, pedagogical understanding is required before a teacher/designer attempts to develop proper instrumentations.

Another critical skill area for successful implementation of assessment of complex learning outcomes is feedback and coaching. Feedback is the first step in motivating individuals to change their behaviors. Continuous assessment requires that the teacher/facilitator or the computer analyze the progress of the learner in order to, not only provide proper feedback, but also assist the learner in adapting or customizing the learning materials and conditions in order to achieve the identified learning outcomes. Future research and development should focus on developing scaffolding or coaching strategies for online teachers and designers. Intelligent tutoring systems are already under development to diagnose learners’ weaknesses, provide individualized on-the-spot feedback, and tailor instruction to the learners’ needs– all with an inhuman degree of patience. By creating a virtual personal tutor that recognizes and adapts to the student’s limitations and emotional distress, online teachers/facilitators can scaffold and support more complex cognitive processes without having to spend a lot of time. Virtual tutors will enhance the role of the teacher/facilitator and offers a better way for the teachers to interact with more learners. An artificial tutor, integrated in an e-learning system, which develops lectures, plans and tailors its behavior towards the student according to the student reactions, and his/her presumed affective states will be the next major development in improving coaching and scaffolding.

Finally, the future work should emphasize multiple assessment methods and tools. Assessing complex learning outcomes encourages multiple and varied assessment techniques. Various assessment techniques and tools should help teachers/designers to gather multiple samples and a sufficient variety of measures of performance. Variety of measurement can be accomplished by assessing the students through different measures that allows the teacher/designer to see them apply what they have learned in different ways and from different perspectives. The future enhancement in online learning environment should make it easier for online teachers to implement and track multiple assessment techniques.

key terms

Assessment Criteria: The statements that express in explicit terms how performance of desired learning outcomes might be demonstrated.

Alternative Assessment: Also referred to as authentic assessment, these measures often require direct examination of student performance using “real-world” tasks requiring complex thinking processes.

Artificial Intelligence: Is the branch of computer science concerned with making computers behave like humans. The term was coined in 1956 by John McCarthy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Authentic Performance Assessment: An authentic performance assessment is a from of assessment that requires students to demonstrate skills and competencies which realistically represent those needed for success in the daily lives of adults. Authentic tasks are worth repeating and practicing.

Complex Learning Outcomes: Refer to integrated sets of learning goals—multiple performance objectives that emphasize coordination and integration of separate skills that constitute real-life task performance. In complex learning, the whole is clearly more than the sum of its parts because it also includes the ability to coordinate and integrate those parts (Van Merrienboer, Clark, & de Croock, 2002).

Learning Outcome: Describes the kinds of things that learners should know or can do after instruction that they did not know or could not do before.

Rubric: A rubric is a rating system by which teachers can determine at what level of proficiency a student is able to perform a task or display knowledge of a concept.