Cancellation of evil Daoist ritual (xiaozai jiangfu)

The cancellation of evil ritual is a type of exorcism practiced today as part of popular Chinese religion. This ritual is performed by Daoist priests of several sects in a public temple or at a private altar. An article of clothing from a person represents the evil or negative influences that "stick" to a person. These influences may be the result of mistakes or transgressions a person has made in the past, or they may be due to birth dates that are not auspicious in a certain time. Whatever the reason, the individual, who is not necessarily present, is able to avoid calamity if this ritual is performed on his or her behalf.

Through ritual action, usually chanting and reading from a Daoist text, the priest transfers the negativity to a paper model, then burns the paper model, and so destroy the influences. A similar ritual can be performed by individual mediums who fall into trance possession states. In such cases the Daoist text may not be used.

Caodaism

Caodaism is a Vietnamese religion that attempts to merge the principles of Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism. Dao Cao Dai (the Great Way), which originated from a merging of themes from Daoism and early 20th-century French spiritism, emerged in the 20th century as the largest indigenous religious movement in Vietnam. In the early 1920s a group of young Vietnamese who had become enthused over the possibilities of spirit contact through the use of mediums approached Ngo Van Chieu (1878-1932), a government official who had been involved with mediumistic phenomena in a Daoist setting. He assisted the group to organize but soon despaired of the direction in which their thought was developing and left. In his place Le Van Trung (d. 1934) and Pham Cong Tac (1890-1959) emerged as future popes. Cao Dai was formally established in a ceremony in 1926.

The new religious group made the seance, in which a medium sits with a number of believers and attempts to contact and relay messages from the spirit world, its central activity, and Dao Cao Dai grew rapidly. Through mediumship, the leaders have received a number of what are considered sacred texts. The mediums have suggested the texts for worship and prayer time. Also, the center shifted from Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) to Tay Ninh, where a large community assembled and a cathedral was built.

The Supreme Being is symbolized with a Great Eye (Thien Nhan). It is the center for meditative activity as members focus on the eye and hope to create conditions for internal changes. A variety of figures from different religions are assigned a lesser status in the divine hierarchy but are seen as objects to whom prayers may be addressed— Buddha, Confucius, Lao Tzu, Jesus, and the novelist Victor Hugo.

Caodaism was significantly affected by the Vietnam War. After the war it had to deal with a new government hostile to all religion, but especially wary of new religions. While the center in Tay Ninh remains the official international headquarters, most believers are now scattered in countries abroad. Most activity now occurs in the lands of the Vietnamese diaspora. A headquarters for believers outside Vietnam has been established at Redlands, California.

Caodong (Ts’ao Tung) school

Caodong was a major historical branch of Chan Buddhism. The school’s name is simply a combination of the surnames of the founder, Dongshan Lingjie (807-869 c.e.), and his successor, Caoqi Benzhi (840-901). As with all extant schools of Chan (Zen), Caodong ultimately descended from the so-called Southern school founded by Hui Neng (638-713), the sixth Chan patriarch. Dongshan Lingjie was a sixth-generation successor to Hui Neng. His lineage eventually resulted, another eight generations later, in the master Dogen Zenji (1200-1253). This Japanese monk introduced the Caodong school to Japan, where it is known as Soto.

It is also sometimes assumed that Caodong was influenced by Shen Xiu’s Northern school and its Yogacara Buddhism school leanings, and that is a possibility. The Cadong school is often seen as emphasizing quiet sitting and meditation, as opposed to the more active "sudden" techniques of such rivals as the Linji Chan, which included the use of koans. However, in fact all the "Five Schools and Seven Sects" of Chan used koans as instruction aids. Although the Soto line has thrived in Japan, Caodong did not last as a separate tradition in China much longer than the Dogen’s time. Chan itself merged into the larger tradition of Chinese monastic practice, including Pure Land and other schools, and did not retain its separate identity as a school.

Carus, Paul

(1852-1919) German-American scholar and early writer on Buddhism

Though not a Buddhist, the editor Paul Carus emerged as a major spokesperson for Buddhism in the West in the early 20th century. He was born in Germany, where his father was the first superintendent of the Lutheran Church of Prussia. Carus received a Ph.D. from Tubingen and began a teaching career. He was eventually forced out of his position as a result of his liberal theological views.

In 1884, Carus moved to the United States. He became the editor of Open Court, an eclectic journal, and eventually married the owner’s daughter. He attended the World Parliament of Religions held in 1893 in Chicago, where he met Anagarika Dharmapala and the Zen master Soyen Shaku. He agreed to head the American chapter of the Maha Bodhi Society and later arranged Dhar-mapala’s 1896 lecture tour in North America. He also worked with Shaku to host Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki, who lived with Carus from 1897 to 1909 and worked on translating a number of Buddhist works.

In 1894 he published his own book, The Gospel of Buddha According to Old Records. This work was one of the first interpretations of Buddhism in a Western language and continues to be used today. It has also been translated into a variety of languages.

Through the several decades after the Parliament of Religions, Carus wrote almost 50 books and published a spectrum of titles on Buddhism and other non-Christian religions. Carus also wrote some poems that were turned into hymns for use in the songbook of the Buddhist Churches of America.

Today the Hegeler Carus Mansion in LaSalle, Illinois, where the press was headquartered, houses a collection of Carus’s work and a library. The building, designed by the well-known architect W. W. Boyington, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Here Suzuki worked with Carus for 12 years, before returning to his native Japan.

A major award, the Paul Carus Award for Outstanding Contributions to the Interreligious Movement, was announced in 2004, at the Parliament for World Religions meeting in Barcelona.

Caves of the Thousand Buddhas

The Caves of the Thousand Buddhas are located in Dunhuang, a town in northwest China along the ancient Silk Road. Buddhist monks began to settle here in the 360s, after a lone monk experienced a vision of 1,000 golden Buddhas. Over the next centuries, the monks turned the nearly 500 caves into a massive Buddhist shrine. Buddhas, bodhi-sattvas, and various divine figures were carved on the walls throughout the cave system.

Along the main route from Central Asia to China, monks wishing to contribute to the effort of transmitting Buddhism to China often stopped at Dunhuang to learn Chinese. Others traveled to the caves to seek certain benefits. For example, women would go to a famous statue of Guan Yin when trying to become pregnant.

Over the centuries, the caves came to house a large library of Buddhist texts. In more modern times they were largely forgotten as the Silk Road lost much of its importance as a trade route. Then in 1907, the explorer Aurel Stein set out for Dunhuang to see whether the description of the place by the eighth-century traveler Xuan Zang could be verified. There he found the large library of ancient texts that had apparently been sealed up in a room in Cave 17. By bribing the abbot of the surviving community of monks, he was able to acquire most of it and take it back to Europe. Among the major items Stein found was the world’s oldest printed document, a copy of the Diamond Sutra, dating to the ninth century.

Today, the caves have become a major tourist spot, and, while the site has been pillaged a number of times, a surprising amount of statues, carvings, and illustrations that decorated the caves have survived. A small community of monks continues to maintain the site.

Central Asia (The Silk Road)

Over the many centuries of Buddhism’s history Central Asia has played a crucial role in its growth and development. Central Asia includes those land-locked states north of the Indian subcontinent, north also of the Tibetan plateau, south of the Siberian landmass, and west of developed East Asia—those places today known as China, Korea, and Japan. For centuries Central Asia was crisscrossed by traders and armies carrying products, customs, and ideas. Their trails are today known as the Silk Road. Buddhism as well as other religions such as Manichaeism and Islam traveled over the well-worn trade routes. For Buddhism, the key period was approximately 100 b.c.e. to 1000 C.E., when many pilgrims and traders moved the Indian concepts and images of Buddhism into and out of the area. Central Asia was a boiling cauldron as well as repository for Buddhist ideas.

Contact between India and Central Asia began very early. Emperor Asoka sent missionaries to Bactria in Central Asia during the third century b.c.e. Inscriptions in stone left by Emperor Asoka’s empire have been found in Gandhara, in present-day Afghanistan.

The best reflection of Central Asia’s role is seen in the vast libraries recovered from Dunhuang, the cave complex at the eastern edge of Central Asia. The 20,000 texts and art pieces recovered there are written in many languages, including Sanskrit, Brahmi, Kharosthi, Tibetan, Turki, Tokharian, Manichean, Syriac, Sogdian, Uighur, and Chinese. Most of the works were written on palm leaves or birch bark, with carvings on wood or bamboo, leather, or, later, paper. In addition to this textual evidence are archaeological sites. There are stupas, temples, and caves still in existence, all decorated with Buddhism figures and frescoes. Luckily for scholars of Buddhism, many sites are well preserved as a result of the generally dry desert terrain. And especially for those areas near China there are many historical accounts of Buddhism’s development in Chinese.

THE SILK ROAD

The sources clearly describe two major trade routes that constituted the Silk Road. These developed in the early years of the Common Era and passed north or south of the great Takla-makan desert, which includes the Tarim Basin. Going west from China, the northern passage transited through Hami, Turfa, Karasahr, Kucha, Aksu, Tumshuk, and Kashgar and finally ended at Samarkand. The southern road went through Miran, Cherchen, Keriya, Khotan, and Yarkand before ending at Herat and, finally, Kabul in present-day Afghanistan. The Silk Road passed through many such city-states, which were often established by groups from Kashmir and northern India, who often claimed connections with Indian royal families.

The monasteries that grew up along these trade routes were often connected to the various schools of Buddhism that had developed in northern India and Kashmir. Many of the monasteries on the southern route followed Mahayana Buddhism, while those on the northern route (Kashgar, Kucha, and Turfan) were connected to Hinayana or Theravadin teachings.

Of all the states on the Silk Route in this period probably Kucha and Khotan were the most important for Buddhism’s history. Many manuscripts are in Kuchan Sanskrit, a form of Sanskrit. And the important scholar Kumarajiva (344-413 C.E.), who was taken to China in 401 c.e. to translate Buddhist texts, was from Kucha.

The northern and southern roads met in China at Yunmen Guan, to the west of Dunhuang. Yunmen is noted for its thousand grottoes or caves with Buddhist-inspired carvings carved between the fifth and eighth centuries c.e. Political developments in India also influenced the spread of Buddhism into Central Asia. The Mau-ryan prince Kunala is said to have migrated and settled in Khotan after leaving Taxila in northern Afghanistan. Chinese accounts note other Indian "colonies" established throughout the area. These oasis cultures played a key role in the Chinese importation of Buddhism.

INTERACTION WITH CHINA

There were most likely two major waves of importation of Buddhism from Central Asia into China. The first recorded instance was a mission headed by the Central Asian monks Kasyapa-matanga and Zhu Fa Lan to China, in 65 c.e. Around the same time the emperor Ming had a dream of a Buddha-like figure who instructed him to invite two Buddhist monks. A monastery, Baimasi (the White Horse Monastery), was indeed constructed for these two missionaries in the Han capital of Luoyang, where they spent the remainder of their days.

As Buddhism became established in successive states throughout the area, more missionaries had contact with China. Tokharestan, a state north of modern Afghanistan, adopted Buddhism, as did the nearby Parthians. The Parthian prince Lokot-tama visited China with numerous Buddhist texts. He remained in China at Baimasi in 144. The Kushan monk An Shigao visited the Han Chinese capital of Luoyang in 148 and began a translation center there. And Lokaksema, a Scythian, worked there from 147 to 189.

Dharmaraksa, from Tokhara, settled in Dun-huang between 284 and 313; there he translated 90 Buddhism works. She Lun, also from Tokhara, arrived in 373, followed by Dharmanandi.

Chinese pilgrims also began to travel to the Central Asian places, and beyond, leaving detailed records. The great northern city of Kashgar was visited by numerous pilgrims. The monks there followed the Sarvastivadin school. The great Chinese translator Xuan Zang (596-664 c.e.) records that the southern kingdom of Khotan had 100 monasteries and 5,000 monks, all following Mahayana. Chinese records from the Jin dynasty (265-316 c.e.) note that Kucha held 1,000 stupas and temples, including nunneries.

MATERIAL CULTURE OF THE SILK ROAD

Other religions flourishing in the Tarim Basin area included Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Manichaeism, all of which influenced Buddhism’s development. However, Buddhism appears to have been the most influential religion during this period, as is reflected in the material culture.

The material culture of the Silk Road was rich and confused. Most inhabitants were nomadic and pastoral. Buddhism, once introduced, became the common thread linking these various small states. Rulers often adopted Indian names and titles, for instance. Slavery was practiced, even in monasteries, and a mild form of caste consciousness appears to have been widespread, limiting intermarriage between different classes. Indian music and dress were also adopted throughout Central Asia.

Economically the societies in Central Asia were agricultural with trade as a sideline. Monks were prosperous and often could marry and own property.

Artistic production, centered on depictions of the Buddha and his lives, flourished. Multiple influences, including Greek, Roman, Persian, and Sassanian, all impacted Central Asian art. The closeness to the trade routes stimulated artistic production, since artists could make a living by selling to the traders. overall Indian and Persian influences were dominant in the south, and Chinese, Tibetan, and Uighur styles were strong in the north. The earliest artistic influence on Central Asia was from Gandhara, in northeast India, which was a center of Greek-influenced art. The paintings in the caves at Dunhuang show a range of styles, including Indian and Tibetan. These date from the fifth to the eighth century c.e. Khotan as well as India also had strong influence on the development of art in Tibet.

Some scholars believe Central Asian beliefs influenced core Mahayana practices. For instance, the bodhisattva Manjusri, worshipped at Mt. Wutai in western China, is said to have been imported from Takharia. And the bodhisattva Kshitigarbha, while originally from India, did not flourish there and only became a major deity figure in Central Asia. Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, is said to have been borrowed from the Zoroastrian deity Ahuramazda.

In addition Tibetan culture had an intimate relationship with those around the Tarim Basin, since Tibetans occupied the area for a period.

LATER DEVELOPMENTS IN CENTRAL ASIA

While the first 500 years of the Common Era saw much Buddhist activity, this came to an end with a series of Arab invasions from the early 600s. In 642 a Sassanian ruler was defeated by Arab armies, and from that point on Buddhist civilization in Central Asia was dismantled, to be discovered by 19th-century archaeology.

Chah, Ajahn

(1918-1981) Thai Forest Meditation Tradition master

The Venerable Ajahn Chah, one of the most well-known Thai Forest Meditation Tradition masters, was born in rural northeast Thailand. He worked on his parents’ farm until the age of 20, then decided to enter the monastic life and was ordained as a BHIKSU. His first years as a monk were spent during World War II, which, along with the death of his father, set him upon an individual search to overcome suffering. While on a pilgrimage in 1946, he learned of the Venerable Ajaan Mun Bhuridatto (1870-1949) and sought him out. Ajaan Mun set him on the simple path of mindfulness meditation characteristic of the Thai Forest tradition. Ajahn Chah spent the next seven years as a wandering mendicant.

In 1954 he accepted an invitation to return to the town near his parents’ farm. He settled in a forest near ubon Rajathani, and as disciples gathered, he built Wat Pah Pong, which became the mother of other monasteries of a similar kind. In 1967 the first Westerner, a recently ordained monk named Sumedho, arrived. He adopted the strict and austere life at Wat Pah Pong. As the Venerable Ajahn Sumedho, he would found another monastery, Wat Pah Nanachat, in northeast Thailand, as a center administered by English-speaking monks for English-speaking seekers.

In 1977, Ajahn Chah, accompanied by Ajahn Sumedho and the Venerable Khemadhammo,visited England. Sumedho and Khemadhammo remained behind to establish the Forest Tradition in England and the West. He made a second visit to England in 1979. However, at the time his health was taking a downward turn. He returned to Thailand and died of diabetes two years later.

Chajang

(seventh century c.e.) Korean Buddhist monk

Chajang, a Korean Buddhist monk, emerged out of obscurity in the 630s when he became one of the first Korean monks to go to China to study. Born in a royal family, he rejected a promising career at court to become a monk. Early in his life he developed a desire to make the pilgrimage to Wutai Shan, a mountain in Shanxi said to be the home of the bodhisattva Manjusri, the embodiment of perfect wisdom. While at Wutai, Chajang chanted before a statue of Manjusri and was given a poem in a dream. unable to interpret the poem, he consulted a local monk, who gave him several relics of the Buddha and told him to return to his home. After a further week of devotional practice, he had a vision in which he was told that the monk was in fact Manjusri and that upon his return home he must build a temple to the bodhisattva.

In 643, Chajang arrived at the mountain Odae-san in southern Korea, where after some waiting he had another encounter with Manjusri. He subsequently built Woljong-sa (Calm Moon Temple), later a major center for disseminating Buddhism throughout the peninsula. Three years later he settled on Yongjuk-san Mountain and from there oversaw the building of Tongdo-sa Temple. Here he enshrined the relics of the Buddha acquired in China. (Woljong-sa was destroyed during the Korean War but rebuilt in 1969. Tongdo-sa had been destroyed during the Japanese invasion in 1592 and reconstructed in 1601.)

Chajang was aided in his Buddhist mission by Queen Sondok (r. 632-646), the daughter of King Chinp’yong (r. 570-632), who followed her father’s program of utilizing Buddhist language to promote her own governmental program, as well as defend her position as a female ruler.

Chan Buddhism

The emphasis on meditation as the essential tool for the practice of Buddhism and the realization of enlightenment is usually traced to India and the image of the Buddha sitting under the Bodhi tree. In India, the emerging movement encountered both Hinduism and Daoism, especially the concept of dhyana, the Indian word commonly translated as "meditation." Dhyana was a practice in Hinduism and Jainism (an Indian movement that grew up alongside Buddhism). Meditation was well established in Buddhism during the Indian era, as may be seen in such writings as the prajnaparamita sutras, which date to the first century b.c.e.

It is in China, however, that the meditative practices that existed as one element in Buddhist practice became the basis of a separate school of Buddhism, which became known as Chan (a Chinese word derived from the Sanskrit dhyana). Most researchers now see the emergence of Chan as based on an isolation of meditative practice and the merger of Buddhist and Daoist mystical concepts, though in Chan practice, meditation had always been more important than any metaphysical/theological speculation. Among the people important to the process of isolating and emphasizing meditation as a practice was Dao Sheng (c. 360-434), who advocated the idea of sudden enlightenment following the pattern set by the Buddha. He also manifested the Chan distrust of scriptures and their study.

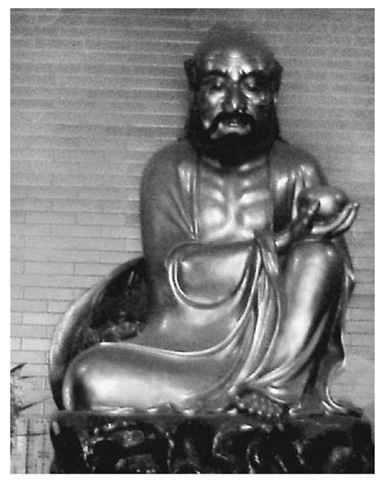

Lacquer image of Bodhidharma, the founder of Chan Buddhism, from the Hualin temple, Guangzhou, southern China

The credit for actually founding Chan is usually assigned to Bodhidharma (c. 470-c. 534), the first patriarch in a lineage of enlightened masters who were able to recognize when others were enlightened and to pass to them a "seal of enlightenment." Bodhidharma is seen as initiating a tradition that understood the inadequacy of words to convey enlightenment and hence passed truth directly to people, who intuitively apprehended it.

We know few details of Bodhidharma’s life. He appears to have been born in southern India, moved to China relatively late in life, and died there around 534 c.e. Around him many semimy-thical stories accumulated. He ended his life as the abbot of the Shaolin (Young Forest) Temple/ Monastery (located near Luoyang, west of the old capital of Xian), and he passed the leadership of the monastery to his successors, the next five of whom would be remembered as the patriarchs of the movement. Bodhidharma passed the inkasho-mei, or seal of enlightenment, directly to the second patriarch, Hui Ke (c. 484-c. 590).

The person recognized as the fourth Chan patriarch, Dao Xin (580-651), settled in one place and built a community of monks who wished to practice meditation. The needs of the new community, not the object of charity from the nearby population, led to Dao Xin’s introduction of a daily schedule that included time for the monks to engage in agricultural work to meet the community’s food needs. Work subsequently was integrated into the monastic life and became another means of practice along with meditation. The development of communities centered on Zen practice also facilitated the participation of lay people in meditation activities in ways not previously available.

The fifth patriarch, Hong Ren (601-674), was the last to preside over a relatively united movement. He passed his lineage to two students, Shen Xiu (606-706) and Hui Neng (638-713). The former, actually the more dynamic of the two, established himself at Luoyang in northern China. Here he developed a variation on the Zen tradition by an emphasis on gradual enlightenment. He built a large following due to his charisma, but his approach to Zen did not long survive him.

Hui Neng has become known as the leader of the so-called Southern school of Chan that maintained the emphasis on instant enlightenment. He saw experience as the way to enlightenment, which occurred in a sudden, direct, and personal apprehension of the self. Word and scriptures were not essential and might actually be distractions. As the northern school of Shen Xiu died out, future Chan lineages would all be traced to Hui Neng, now considered the sixth patriarch. His status is manifest in the collection of his discourses in an authoritative volume, the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch.

And beginning with Hui Neng, Chan flourished in China, at least for the next century. During this time, the use of the koan (a practice usually attributed to Mazu [707-786]) would be introduced. The koan is a story or question or image that defies a rational response and hence pushes the student toward intuitive jumps. De Shan (780-865) is credited with introducing the stick with which the master would strike students to take them to the present and, it was hoped, shock them into sudden enlightenment. Bo Zhang (749-814) compiled and codified the rules that would regulate monastic life, the monasteries where people could engage in the daily routine of "work, live, meditate, sleep," advocated by Dao Xin. To Bo Zhang is attributed the saying "One day without work means one day without food."

The development of Hui Neng’s students encountered a disastrous moment during the reign of the emperor Wuzong (r. 840-846). Rising to the throne during a time of economic crisis, the emperor eventually gazed upon the Buddhist monasteries as a solution to his cash flow problem. He confiscated many of the monasteries and scattered the monks, forcing them back into a secular lay existence. Wuzong’s persecution (which extended to other religions as well) was an almost fatal wound to the Zen community. It took a generation to revive and never fully overcame the effects. During the late ninth century, the revived community would divide into five major sects, called the Five Houses. Of these, two would become dominant, the Linji (later transferred to Japan as Rinzai Zen) and the Caodong (in Japan as Soto Zen) schools.

Linji Chan, which took its name from its main center located at Linji, was founded by Yi Xuan (also known as Gigen) (d. 867). Over time, Linji Chan would divide into a number of different schools, each characterized by a unique lineage of leaders, though each could be traced to Yi Xuan.

Caodong Chan took its name from its two founders, Cao Shan (840-901) and Dong Shan (807-869), who in turn had adopted their religious names from the mountains on which they resided. Caodong emphasizes zazen, sitting in meditation, a practice that if pursued over time leads to enlightenment. Caodong thus reintro-duced a form of the gradual enlightenment advocated by Shen Xiu.

Stone image of Muso Kokushi (1327-1351), Rinzai Zen priest, founder of Zuisen-ji and builder of many Japanese gardens, in the garden of the Zuisen-ji, Kamakura, Japan

Chan would be introduced into Japan (where it would be called Zen) in the seventh century, and the island nation would receive regular new injections. The most important transmission of Chan would occur in the 12th and 13th centuries when Linji Chan would be introduced by Eisai (1141-1215) and Caodong by Dogen (1200-53).

During China’s Song dynasty (960-1279), Chan Buddhism was able to recover somewhat, and with Pure Land Buddhism would become one of two major schools of Chinese Buddhism. In many places, practitioners of the two schools shared a single monastic facility, a practice that led to the blurring of the lines between Pure Land and Chan life.

Among the interesting developments within the Chan community, the monks at Shaolin responded to the unrest in China during the time of Wuzong and his predecessors by inviting practitioners of the martial arts to the monastery. The monks compiled the knowledge from different teachers and over time developed the major center for the teaching and practice of kung fu, which was integrated into the Zen culture.

Chan survived through the centuries in China in spite of the ups and downs of various dynasties that favored other forms of Buddhism, including Vajrayana. It would face its greatest test in the 20th century after the Chinese revolution and antireligious policies adopted by the People’s Republic of China, which led to the closing (and even destruction) of many Chan monasteries and the transformation of many of the leading Chan monastic centers into tourist attractions.

The Chinese revolution also led to the diffusion of Chan Buddhism, first to Taiwan and then to other communities of the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia and the West. Prominent among the diaspora Chan communities are the Dharma Drum Mountain Association and Foguangshan, both based in Taiwan.