The megalithic structures of the islands of the Maltese archipelago are the earliest freestanding buildings in world, dating from the fourth millennium b.c. They form a class of megalithic monument unparalleled in the prehistoric central-western Mediterranean area, since they are ceremonial and habitable structures rather than the more familiar megalithic mortuary constructions of western Europe. Some thirty such structures, mostly grouped together in local clusters, also include mortuary temples constructed belowground, which seem to have functioned as temples for the dead, with the insertion of hundreds or even thousands of burials over several centuries. In one case, Brochtorffs Circle at Xaghra on the island of Gozo, the mortuary complex of natural caves was surrounded by a mega-lithic circle and connected via a ceremonial path, marked by other megalithic monuments, to the Ggantija temple complex about half a kilometer distant. This complex appears to be one of the earliest in Malta, with the main temple dating from the Ggantija phase at the beginning of major temple building. Massive landscape change and dense settlement in modern times have obscured or destroyed the settings of many sites, and their original extent remains unclear.

RELATIONSHIP TO EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN PREHISTORY

The appearance of megalithic monuments in the western Mediterranean represents an earlier episode in Neolithic activity than the blossoming of prehistoric Maltese architecture. These early phases were invariably linked to the varied tomb-building traditions, especially those in France, Spain, and Portugal. These dolmens date from the late sixth millennium to the late fourth millennium b.c. and link the western Mediterranean with the Atlantic coast within a shared tradition of passage graves, dolmens, gallery graves, and other rough standing-stone structures and menhirs (individual standing stones). The Maltese temples (fourth to third millennia b.c.) appear to have developed locally, without apparent links to other cultures in the Mediterranean; indeed the crude dolmens of the Bronze Age (second millennium b.c.) of Malta seem to postdate the completion of the temples by centuries.

Early cultural links, however, are documented in the origins of Neolithic settlement on Malta, which has strong affiliations with the Stentinello culture of Sicily and Calabria. Similar stamped and impressed pottery with geometrically arranged decorations (Ghar Dalam style); Neolithic artifacts, such as polished stone axes and obsidian and flint tools; agricultural practices; and raw materials derived from Sicily, Italy, and the surrounding islands, suggest colonization of the Maltese islands from Italy rather than from other zones of the Mediterranean. The first settlement was in the mid-sixth millennium b.c., and a relationship between Malta and southern Italy and Sicily was maintained for at least another millennium in the sharing of similar cultural identities and raw materials, such as "Diana" style pottery (a red-slipped pottery with distinctive trumpet-shaped lugs and rounded forms) and obsidian. Thereafter close cultural similarity with Italy and Sicily ceased, and the distinctive Maltese Temple cultures became dominant, without apparent inspiration from elsewhere. Curiously, though, the material culture of Sardinia bears similarities in complex pottery forms (such as tripods and decoration), burial monuments (such as multiple-chambered rock-cut tombs), and iconography in the form of menhirs with heads, fat figurines, and sculptures of the human form.

LOCATION

The Maltese islands lie at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, between Sicily and southern Italy and Tunisia in North Africa, and roughly midway between the eastern and western Mediterranean. The location is remote in terms of Mediterranean islands, however, and Malta appears to have remained uninhabited by early human groups until agriculture became well established in the Neolithic. The distances—80 kilometers from Sicily and 290 kilometers from Tunisia—meant that navigation by small seagoing craft in prehistory was always a rather precarious activity, and thus Malta was more isolated culturally and economically than most other islands in the Mediterranean. The agricultural conditions on the islands were fertile, and the limestone-clay landscape provided an environment rich enough to support dense prehistoric populations and a variety of raw materials. Environmental reconstruction of the prehistoric landscape suggests that the originally wooded islands were cleared rapidly of their tree cover and that one basic resource thereafter was scarce—sizable quantities ofwood for buildings or boats.

CHRONOLOGY

Archaeological research over the last three or four decades of the twentieth century established a secure radiocarbon sequence of absolute dates for Malta’s prehistory and demonstrated the great antiquity of the temples. The dates of course provide an estimated carbon-14 range rather than a precise calendar, and the dating of stone buildings is always beset with problems. At present there is no sign of a Palaeolithic-Mesolithic occupation, and the first settlement is dated to about 5000-4300 b.c., with the Ghar Dalam phase of impressed pottery and early farming. The later Neolithic Grey and Red Skorba phases date from about 4500-4000 b.c., the latter associated with increasingly complex ritual sites and material culture. The Early Temple period is defined by the Zebbug and Mgarr phases, around 4100-3600 b.c., when small family rock-cut tombs and curious rounded structures were built. The first large and impressive temples date from the Ggantija phase, c. 3600-3200 b.c., when culturally the Maltese islands displayed structures and material wholly different from neighboring regions in Sicily and Italy. The main flowering of the temples occurred over the next millennium, with the Saflieni (33003000 b.c.) and the Tarxien periods (3000-2500 b.c.), when many temples were built and earlier ones enlarged and embellished.

The Temple culture appears to have ceased abruptly in the middle of the third millennium and was replaced by an apparently intrusive culture bearing close similarity to the Early Bronze Age cultures in southern Italy and Sicily. The newly introduced rite of cremation burials, metalwork in a nonmetal-working technology, and very different pottery and artifacts, such as curious flat Helladic-style figurines and a locally distinctive ceramic tradition with stylistic links across the central Mediterranean, confirm a total break with the previous indigenous cultural sequence. These Bronze Age cultures, the Tarxien cemetery and its successor the Borg-in-Nadur, developed locally but in parallel with Mediterranean neighbors in Pantelleria, Sicily, and southern Italy.

KEY FEATURES

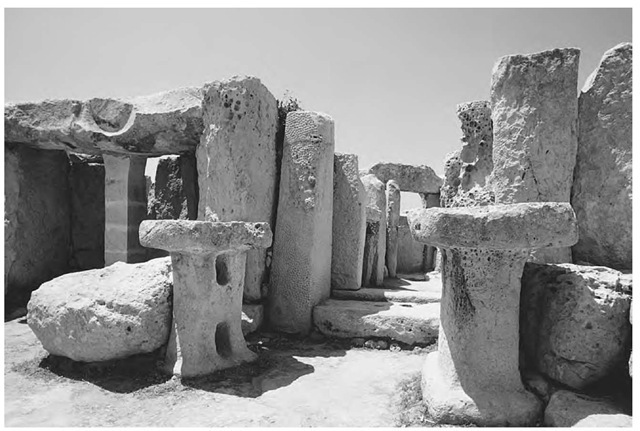

The so-called temples were built of local limestones, from a combination of unworked and rough coralline and smoothly cut, shaped, and carved softer globigerina limestone. The stone is important, since very large rough slabs allowed for the realization of the huge megalithic structures, which then were embellished with the finely finished softer stone. The temples normally were arranged in a series of semicircular apses around central corridors in a trefoil form, which in turn opened to an entrance shaped by impressive trilithons and threshold steps facing a large, open court. Some courts, as at Ggantija, were on raised manmade terraces and form an impressive approach to the high, curved facade of the temple. The size of the individual apses and temples seems to have been limited by building materials, where the length of stone or timber to span roofs may have been restricted.

Typical apses are between 5 and 8 meters in diameter and, when paired across the corridor, allow a maximum width of 15 to 20 meters. The depth of many temples is some 20 to 30 meters, and the whole then is encapsulated within massive outer walls and a facade. The most elaborate and late temples, such as Tarxien and Hagar Qim (fig. 1), have complex ground plans around several separate corridors and entrances, whereas the earlier and simpler structures focus on an end apse with pairs of apses on either side, usually two or four, as seen at Ggan-tija and Mnaijdra north.

The artistic embellishments to the temples in the form of carvings, reliefs, pecked and drilled stone surfaces, altars, painted plaster walls, and finely finished plaster floors are a particular characteristic of Maltese temples. Decorative forms include floral and geometric patterns, spirals, animals, and human forms and are remarkably sophisticated, rivaling art in contemporary Egypt or the Near East. The shape of stones and their finish was significant, and altars made up of stones in pillar and triangle forms, as at Hagar Qim and Brochtorff Circle, appear to be shrines to male and female genitalia and thus perhaps fertility symbols. In other examples, plants, stacked ram’s horns, rows of male animals, or carvings of suckling pigs may have comparable symbolic associations.

FINDS

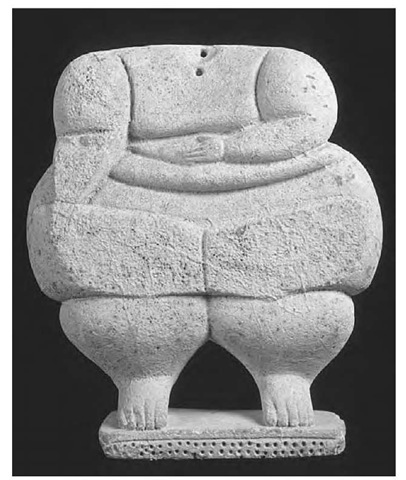

The material culture of the Temple period is remarkable for its craftsmanship and unique style. Pottery developed distinctive forms and handles, with jars, cups, and bowls designed for domestic use and for ritual feasting. There also were miniatures for ritual offerings. Dumps around some temples have revealed great quantities of drinking cups and jars, indicating the scale of use. Stone tools made from imported rock, obsidian, and flint or local chert were formed into knives, scrapers, and axes. Greenstone was imported from Italy and ground into tiny axe amulets, which often accompanied the dead as grave goods. Animal bones were carved into utilitarian tools (spatulas, points, and needles) and also beads and amulets, along with seashells, which were used as personal ornaments and even musical instruments. The most distinctive objects are the figurines and phalluses made from clay and stone. These items include the famous "fat ladies"—small and large seated or kneeling figurines, standing skirted priest figures, and a range of both realistic and highly symbolized human forms (fig. 2). A rare group includes human and fish figures seated or lying on couches, known principally from the hypo-gea (underground burial chambers), although a huge pair of seated stone figures is included in the outer wall of Hagar Qim. A cache of six stick figures was found together with three other carvings at the Brochtorff Circle; they represent a new category of cult figure. The location of such finds appears, from surviving archaeological records, to be highly significant, since figurines and cult material seem to be placed in close proximity to shrines, altars, and thresholds into special areas and under floors.

ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

The temples have been subject to much study since they were discovered in the late eighteenth century, and interpretations have changed alongside the developing discipline and fashions in archaeology. Themistocles Zammit undertook the first significant research early in the twentieth century, first with his work at the Hal Saflieni Hypogeum and then with the excavation of Tarxien Temple. Earlier only clearance and crude excavation had taken place, removing without record the bulk of preserved sediment at the majority of temple sites. Zammit recorded material carefully and presented his findings to a wide community. Work by John Evans in the 1950s followed by that of David Trump in the 1960s provided new data, phasing, dating, and publications, enabling comparative studies of Malta and establishing the antiquity of the prehistoric sequence. Of the thirty or so known individual temples, there are about twenty complexes that remain sufficiently intact to assess their form and scale. They each comprise two to five structures, some of which are apsed temples and others of which are ancillary buildings. The reduced state of many sites means that interpretation is difficult, and few have been systematically excavated or studied. One area of potential research has been the orientation of the temples, which shows a consistent pattern: temples face south, southeast, or southwest, looking out from their entrances. Equally this orientation might be reversed (as in a Christian church), and then the view from the entrance of the Maltese temples would be looking north at the altars.

The repeated form of the temples and the clearly demarcated areas within them signal that they are not domestic houses but instead have a ritual function. The locking holes in doorjambs, the restricted lines of sight from the entrances to the areas within, the large ceremonial courtyards outside, and the apparently large quantities of exotic, rare, highly stylized artistic objects and decoration all suggest a ritual or cult use. Studies have focused on the role of ritual specialists, perhaps those portrayed in the so-called priest figurines, who may have controlled access and activity in the temple complex. The large quantities of animal bone stacked within Tarxien and the dumps of pots and bones at other sites, such as Ggantija, indicate the slaughter of animals and special feasting and consumption of food and drink on a large scale. The scale of prehistoric Maltese populations has been much discussed, since the rocky 314 square kilometers (121 square miles) could support only a limited population, estimated variously between five thousand and ten thousand people maximum. The twenty separate temple complexes may have served local communities of only three hundred to five hundred people and may have been built for a variety of different functions and cults.

Fig. 1. Monolithic altars stand at the ruins of Hagar Qim, a Neolithic temple on Malta. The pits and pockmarks in the limestones are caused by long-term erosion.

Fig. 2. This figurative statuette, now headless, once stood at Hagar Qim. Male and female forms at Neolithic temples could be standing, seated, or kneeling, and depictions ranged from realistic to highly symbolized.

Only two sites currently have associated burial hypogea—Tarxien with Hal Saflieni and Ggantija at Xaghra on Gozo with the Brochtorff Circle. Crude estimates at Hal Saflieni in about 1910 suggested on the basis of one recorded chamber a potential population of seven thousand buried people. The much disturbed (and still incompletely excavated) site of Brochtorff Circle produced more than 200,000 human bones, representing a minimum population of 800 people. As Colin Renfrew has shown, however, when the long time scale of use of these hypo-gea is tallied with the total number of individuals, the contributing population is quite small, with the addition of only a few corpses each year.

COMPARABLE SITES

The Maltese temples have no direct parallels and form a unique group of sites. The closest parallels are burial sites found in contemporary Sicily and Sardinia, where the tradition of rock-cut tombs evolved along with that of Malta. In Sardinia the Ozieri culture, in particular, is noted for elaborate hypogea, which involve several chambers and passages and the carving (and ochre painting) of such forms as bulls’ horns. Figurines also were carved, and the small, fat, and detailed figures of the Late Neolithic Bonu Inghinu and the Ozieri flat steatite figurines offer a broad parallel to Maltese art. A large site in southeastern Sicily at Calaforno is a comparable burial complex.

SIGNIFICANT ADVANCES

The work at the Brochtorff Circle at Xaghra on Gozo (1987-1994) has enabled the first detailed study of the human populations of early Malta and has shown details of population structures, disease, health, and burial ritual that were hitherto unknown. Over the long occupation of the site, the buried population apparently became less well nourished, as shown by the state of teeth as well as through studies of child and infant bones, where deficiencies in vitamins and minerals appear to have been significant. This may be an indicator of overpopulation and general economic stress toward the end of the Temple period and may help explain the collapse of the Temple culture.

Other factors to explain the Maltese temples are under discussion, such as: the apparent lack of fish in the diet; the enormous physical investment in temple-building activity; the possible political structures that directed activities, tribute, redistribution, and production; and indeed the old explanation of invaders, famine, and disease. Advances in understanding depend on future fieldwork on settlement (evidence of which is elusive and mostly destroyed), genetics, economics, and environmental change. A major initiative, in the form of protective conservation legislation, has begun to ensure the future preservation of the sites, especially those inscribed as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO, at Ggantija, Tarxien-Hal Saflieni, Mnaijdra, and Hagar Qim.

Since the late nineteenth century European prehi-storians have pondered the significance of the megaliths, fortified settlements, and decorated figurines of the Late Neolithic and Copper Age of Iberia, including the Balearic Islands. Many early scholars, such as the French prehistorian Emile Cartailhac and the Belgian mining engineer Louis Siret, attributed the development of these cultural features to invasions by or contacts with distant eastern Mediterranean cultures, such as the Myce-naeans, Minoans, Phoenicians, or Egyptians. The development of radiocarbon and thermolumines-cent dating in the 1960s, however, undermined these traditional frameworks and demonstrated that Late Neolithic and Copper Age Iberian cultures predated or were roughly contemporary with their supposed eastern Mediterranean inspirations. There is also no archaeological evidence that similar objects originated in the eastern Mediterranean at this time, as some prehistorians of the late nineteenth century also noted. For these reasons archaeologists interpret the cultural transformations of the Late Neolithic and Copper Age of Iberia as the product of local sociopolitical, economic, and ecological forces. There were certainly, however, exchange networks or contacts among groups within the Iberian mainland, among mainland groups and populations on the Balearics, and among Iberians and peoples in North Africa and the western Mediterranean in general. Archaeologists are engaged in assessing the nature of these interactions and their role in the evolution of late prehistoric Iberian societies.

CHRONOLOGY

The Late Neolithic and Copper Age of the Iberian Peninsula lasted from 4500 to 2200 b.c. The Late Neolithic (sometimes referred to as the Almeria culture in southeastern Spain or the Alentejo culture in southern Portugal) dates from 4500 to 3250 b.c. and was associated with the construction of the first megalithic tombs and the establishment of hilltop settlements. The Copper Age (also known as the Chalcolithic, Eneolithic, Vila Nova de Sao Pedro [VNSP] culture, Los Millares [LM] culture, or Bronce I) lasted from 3250 to 2200 b.c. and was characterized by the development of copper metallurgy, fortified settlements, and new ceramic types, such as bell beakers. In the Tagus River estuary of Portugal and in southeastern Spain it is possible to subdivide the Copper Age into a pre-beaker, Early Copper Age (3250-2600 b.c.) and a beaker, Late Copper Age (2600-2200 b.c.). Those archaeological sites that provide the best chronometric evidence for cultural changes between the Late Neolithic and Copper Age are Zambujal, Penedo de Lexim, Cas-telo de Santa Justa.