Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

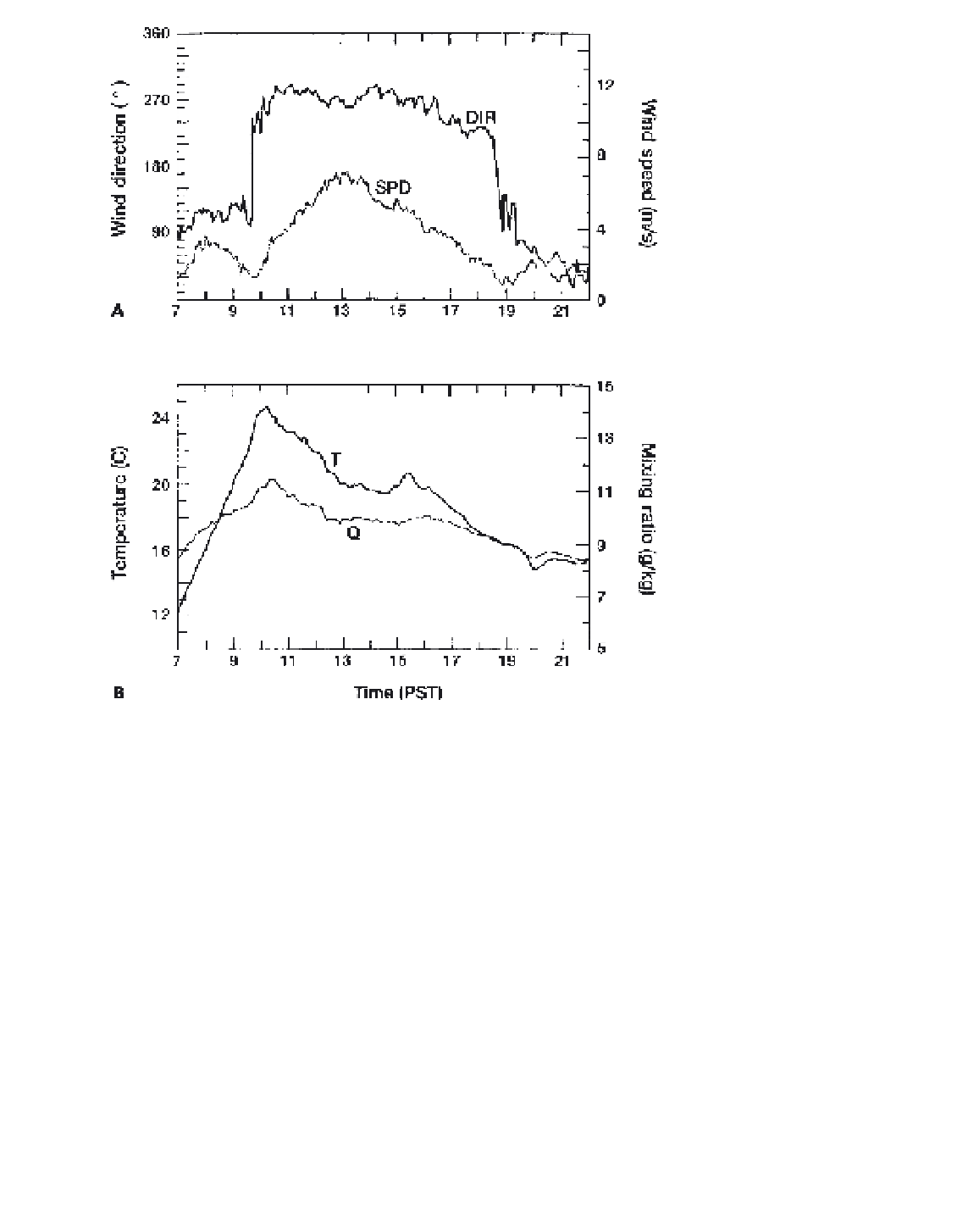

Figure 6.12

The effects of a westerly

sea breeze on the California coast on

22 September 1987 on temperature

and humidity. (A) Wind direction (DIR)

and speed (SPD). (B) Air temperature

(T) and humidity mixing ratio (Q) on a 27-

m mast near Castroville, Monterey Bay,

California. The gradient flow observed in

the morning and evening was easterly.

Source

: Banta (1995, p. 3621, Fig. 8), by

permission of the American Meteorological

Society.

northern hemisphere) so that eventually it may blow

more or less parallel to the shore. Analogous 'lake

breeze' systems develop adjacent to large inland water

bodies such as the Great Lakes and even the Great Salt

Lake in Utah.

Small-scale circulations may be generated by local

differences in albedo and thermal conductivity. Salt flats

(playas) in the western deserts of the United States and

in Australia, for example, cause an off-playa breeze by

day and an on-playa flow at night due to differential

heating. The salt flat has a high albedo, and the moist

substrate results in a high thermal conductivity relative

to the surrounding sandy terrain. The flows are about

100 m deep at night and up to 250 m by day.

and buoyant (see Chapter 5B), whereas stable air returns

to its original level in the lee of a barrier as the grav-

itational effect counteracts the initial displacement. This

descent often forms the first of a series of

lee waves

(or

standing waves

) downwind, as shown in Figure 6.13.

The wave form remains more or less stationary relative

to the barrier, with the air moving quite rapidly through

it. Below the crest of the waves, there may be circular

air motion in a vertical plane, which is termed a

rotor

.

The formation of such features is of vital interest to

pilots. The presence of lee waves is often marked by

the development of lenticular clouds (see Plate 7), and

on occasion a rotor causes reversal of the surface wind

direction in the lee of high mountains (Plate 13).

Winds on mountain summits are usually strong, at

least in middle and higher latitudes. Average speeds on

summits in the Colorado Rocky Mountains in winter

months are around 12 to 15 m s

-1

, for example, and

on Mount Washington, New Hampshire, an extreme

value of 103 m s

-1

has been recorded. Peak speeds in

3 Winds due to topographic barriers

Mountain ranges strongly influence airflow crossing

them. The displacement of air upward over the obstacle

may trigger instability if the air is conditionally unstable