Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

C LOCAL WINDS

air in a valley is laterally constricted, compared with

that over an equivalent area of lowland, and so tends to

expand vertically. The volume ratio of lowland/valley

air is typically about 2 or 3:1 and this difference in

heating sets up a density and pressure differential, which

causes air to flow from the lowland up the axis of the

valley. This valley wind (Figure 6.10) is generally light

and requires a weak regional pressure gradient in order

to develop. This flow along the main valley develops

more or less simultaneously with

anabatic

(upslope)

winds, which result from greater heating of the valley

sides compared with the valley floor. These slope winds

rise above the ridge tops and feed an upper return current

along the line of the valley to compensate for the valley

wind. This feature may be obscured, however, by the

regional airflow. Speeds reach a maximum at around

14:00 hours.

At night, there is a reverse process as denser cold air

at higher elevations drains into depressions and valleys;

this is known as a

katabatic

wind. If the air drains down-

slope into an open valley, a 'mountain wind' develops

more or less simultaneously along the axis of the valley.

This flows towards the plain, where it replaces warmer,

For a weather observer, local controls of air movement

may present more problems than the effects of the major

planetary forces discussed above. Diurnal tendencies

are superimposed upon both the large- and the small-

scale patterns of wind velocity. These are particularly

noticeable in the case of local winds. Under normal

conditions, wind velocities tend to be least about dawn

when there is little vertical thermal mixing and the lower

air is less affected by the velocity of the air aloft (see

Chapter 7A). Conversely, velocities of some local winds

are greatest around 13:00 to 14:00 hours, when the air

is most subject to terrestrial heating and vertical motion,

thereby enabling coupling to the upper-air movement.

Air always moves more freely away from the surface,

because it is not subject to the retarding effects of

friction and obstruction.

1 Mountain and valley winds

Terrain features give rise to their own special meteo-

rological conditions. On warm, sunny days, the heated

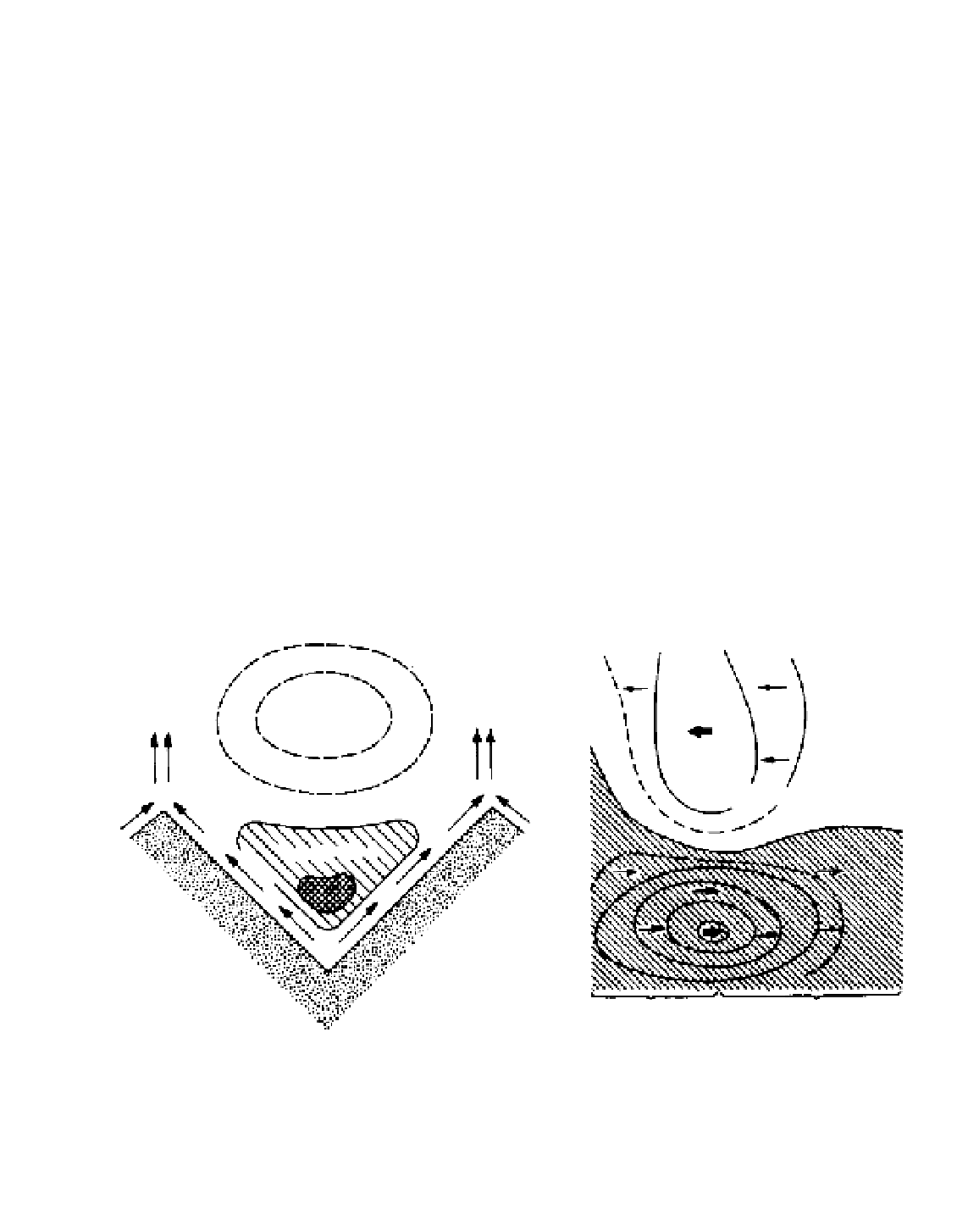

Anti-valley

wind

div.

div.

Ridge

wind

Ridge level

Valley wind

Plain

Distal

end

Valley

Proximal

end

A

B

Figure 6.10

Valley winds in an ideal V-shaped valley. (A) Section across the valley. The valley wind and anti-valley wind are directed

at right angles to the plane of the paper. The arrows show the slope and ridge wind in the plane of the paper, the latter diverging (div.)

into the anti-valley wind system. (B) Section running along the centre of the valley and out on to the adjacent plain, illustrating the valley

wind (below) and the anti-valley wind (above).

Source

: After Buettner and Thyer (1965).