Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

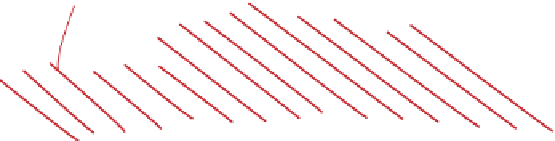

Figure 10.8

An example of a

sketch section, redrawn from a

notebook, based on observations

of cleavage and bedding attitudes

and minor fold structures on a road

traverse in the northwest Himalaya.

Numbers refer to localities. The

kilometre-scale antiformal fold

inferred here is a subordinate

structure on the SW-dipping limb of

a 20-km-scale syncline. (Tom W.

Argles, The Open University, UK.)

10

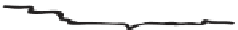

Sketch sections such as the example in Figure 10.8 are not

intended to be accurate, but to focus attention on structural

problems and try out ideas of the regional geology. They may

even direct mapping, for instance by identifying the best

location(s) to visit in order to test a hypothesis. This may be an

iterative process in areas of poor exposure, and a certain

amount of trial and error may be required to deduce the

thicknesses of lithological units that produce a geologically

reasonable cross-section.

10.5 Mapping techniques

You should always aim to record as much relevant detail as

practical in your notebook to help construction of the fi nal

geological map. Some features (e.g. uniformly dipping strata)

can be adequately recorded with a few measurements. Others,

such as complex brittle fault zones, may require numerous

measurements and observations to constrain their orientation

and kinematics satisfactorily. Mapping may be focused on

different aspects of the geology (e.g. bedrock, superfi cial

deposits, artifi cial deposits, mineral deposits, glacial

geomorphology, soils), which will impose different constraints

on the mapping techniques used. In addition, other constraints

such as time, terrain, vegetation, weather, etc., mean that you

must develop an appropriate mapping strategy for the

conditions. Three common mapping methods are described in

the following sections, although in some areas a combination of

these different techniques may be appropriate.

Whichever mapping technique is employed, it is good practice

to constantly develop hypotheses that predict what you will

fi nd at the next exposure. Then on arrival, the prediction (e.g.

the dip will have changed, it will be the same rock type) is

tested immediately. If correct, the hypothesis is supported; if

wrong, you may need to develop a new hypothesis - for

instance, a fold axis or fault has been crossed between the two

exposures.