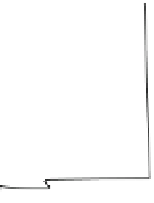

Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

1.Manitou Experimental Forest, CO, Boyden et

al. 2005.

W 109

2. Turkey Springs, San Juan Mountains, CO,

Romme unpublished

Colorado

Utah

3. Archuleta Mesa, NM, Brown and Wu 2005.

1

4. Monument Canyon Research Natural Area,

NM, Falk and Swetnam, unpublished.

3

N 37

5.Chuska Mountains, AZ, Savage 1991.

2

6

5

6. Powell Plateau, Grand Canyon National Park,

AZ, Fule et al. 2002.

7

4

8

7. Walhalla Plateau,

AZ, Mast & Wolf 2004.

Grand Canyon National

New Mexico

9

Park,

10

8. Gus Pearson Natural Area, AZ, Mast et al.

1999.

Arizona

11

12

9. Maverick Fort Apache Reservation, AZ,

Cooper 1960.

Km

10. Malay gap, San Carlos Reservation, AZ,

Cooper 1960.

200

0

400

Mexico

11. Santa Catalina Mountains, Iniquez and

Swetnam, unpublished.

12. Rhyolite Canyon, Chiricahua National

Monument, AZ, Barton et al. 2001.

Fig. 9.9

Map of the Southwest and southern Rocky Mountains showing locations of the 12 sites

where ponderosa pine age structure data have been collected and composted for analysis in this

chapter. The

gray shaded

area is the approximate range of ponderosa pine in this region

of trees also appear to approximately coincide with drier periods in the 1750s-

1760s, 1850s-1860s, and 1950s-1960s. Note also that a most recent cohort in the

1980s-1990s also coincides with a wet period in the Southwest that occurred from

datasets used here lack counts of tree seedlings and saplings in these recent decades.

Earlier wet periods (1610s-1640s and 1690s-1710s) may coincide with very slight

establishment episodes, but these cohorts are not well resolved, probably because

fewer trees overall are included in this earlier part of the record.

Although this is a relatively coarse-scale spatial and temporal analysis of pon-

that there are several key features of local to regional recruitment dynamics that

were responsive to climatic variability. It is well known that ponderosa pine pro-

duces large cone crops only erratically, and that successful germination of the seeds

establishment and survival of seedlings into saplings is dependent on (1) favorable

moisture conditions (i.e., lack of drought), (2) the absence of surface fires for a suffi-

cient length of time to allow the saplings to develop thicker, more heat-resistant bark