Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

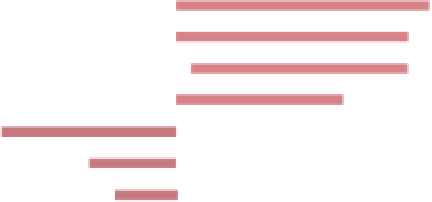

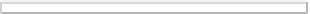

Magnetic susceptibility (SI)

10

-5

10

-4

10

-3

10

-2

10

-1

10

0

10

1

10

2

Haematite

Monoclinic pyrrhotite

Minerals

Ilmenite/titanohaematites

Paramagnetic minerals

(Titano) magnetites/maghaemite

Disseminated

Massive/coarse

Basalt/dolerite

Gabbro/norite

Spilites

Felsic volcanics

Andesite

Granite/granodiorite/tonalite

Ilmenite series

Magnetite series

I type

Igneous

S type

Trachyte/syenite

Monzonite/diorite

Pyroxenite/hornblendite

Phonolites

Kimberlites

Peridotites (including dunite)

Serpentinised

Metasediments

Amphibolite/mafic granulite

Metamorphic

Felsic granulite

Skarn

Magnetite skarn

Siliciclastics, shales

Sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks

Carbonates

Banded iron formation

Haematite-rich

Magnetite-rich

Laterite

Mineralisation

Haematite-goethite-rich

Maghaemite-bearing

Figure 3.42

Susceptibility ranges for

common minerals and rock types.

The darker shading indicates the

most common parts of the ranges.

Redrawn with additions, with

Sulphide-oxide

mineralisation

Pyrite-rich

Haematite-rich

Pyrrhotite-rich

Magnetite-rich

Paramagnetic

limit

Steel

10

-5

10

-4

10

-3

10

-2

10

-1

10

0

10

1

10

2

the magnetic grains occupy more than about 20% of the

rock volume the relationship becomes substantially non-

linear and susceptibility increases faster. This is because the

strongly magnetic grains are packed closer together,

increasing interactions between the grains. For weakly

magnetic minerals, such as haematite and paramagnetic

species, susceptibility is essentially proportional to the

magnetic mineral content, right up to 100% concentration.

Figures 3.42

and

3.43

show the variation in susceptibility

and Königsberger ratio (see

Section 3.2.3.4

)

for common

rock types. All of the signi

cantly magnetic minerals are

accessory minerals, except in certain ore environments.

Their presence or absence is largely disregarded when

assigning a name to a particular rock or rock unit. Since

it is the magnetic minerals that control magnetic

responses, there is no reason to expect a one-to-one cor-

relation between magnetic anomalies and geologically

mapped lithological boundaries. In most cases the overall

magnetism of

rocks

re

ects

their magnetite content,

because of magnetite

s common occurrence and strong

magnetism. Consequently, magnetic maps are often

described as

'

'

magnetite-distribution maps

'

, which for most

types of terrain is a valid statement.

Magnetic susceptibility varies widely in all the major rock

members with high and low susceptibilities re

ecting the

presence or absence, respectively, of ferromagnetic minerals

along with

paramagnetic

species. The

range

in

Search WWH ::

Custom Search