Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

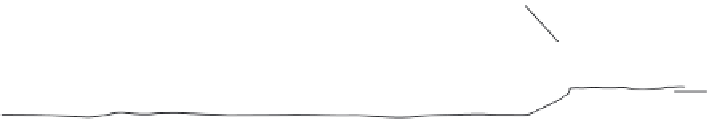

Figure 18.4 Formation of the Basin and

Range.

The Basin and Range Province

consists of a series of normal faults pro-

duced by stretching of the continental crust

over the past 20 million years. After uplift,

erosion attacks the mountain ranges (horsts).

The resulting sediments are then deposited

in the intervening basins (grabens), slowly

filling them with sediment.

Graben

(basin)

Horst

(upthrown block)

Fault planes

Horst

(upthrown block)

applied by an underlying magma plume. As a result of this

stretching, the crust thinned, cracked, and pulled apart, creat-

ing numerous normal faults that have planes inclined at about

a 60° angle (Figure 18.4). This faulting created the series of

alternating basins and ranges that characterize the area.

The importance of rock structure can also be seen where the

rocks are horizontal and have not been deformed (Figure 18.5).

In these areas, which are very common in the West, the rocks

usually consist of alternating layers of limestone, sandstone,

and shale that contribute to a distinctive pattern of differential

weathering. The limestones and sandstones are generally the

most resistant rocks to erosion, whereas the shales are rela-

tively soft and thus easily eroded. Where these patterns occur,

the hard rocks usually form a resistant caprock that protects

the underlying shale to some extent from erosion. Notice in

Figure 18.5 that shale tends to form shallow slopes, whereas

the more resistant rocks are associated with steep slopes. Shale

tends to erode backward gradually due to slope wash when it

does rain. This gradual slope retreat ultimately undermines the

caprock above and causes it to collapse due to rockfall, and the

cycle begins again.

The net effect of this kind of landscape evolution is

that large parts of the western United States are extensively

dissected (appear to be cut up), with upright landforms of

various sizes that rise above the surrounding lower ground.

To the novice these landforms seem to have some relation-

ship to one another, but it is difficult to imagine how they

could be related. Actually, this landscape represents a slow

progression of erosion over millions of years. Figure 18.5

illustrates the landforms associated with this progressive

evolution. It is interesting to notice how each of the rock

layers can be visually traced from one landform to another.

This linkage occurs because the rock was once a uniform

mass with broad regional extent. Through a combination of

stream erosion, differential weathering, and mass wasting

over millions of years, the landscape was slowly dissected,

leaving a succession of flat-topped remnants that tower

throughout the area.

Playa

Plain

Canyon

Mesa

Pediment

Mesa

Butte

Resistant cap rock

(limestone or sandstone)

Plateau

Pinnacle

Nonresistant rock

(shale)

Figure 18.5 Prominent desert landforms associated with horizontal rock structure.

Over time, a plateau

is dissected into progressively smaller landforms that give the region a distinctive appearance.