Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

What Is Soil?

Although all soils can be viewed in these various ways, they nev-

ertheless vary dramatically in terms of their character and thick-

ness, ranging from a few centimeters to several meters in depth.

Soils are indeed one of our most important natural resources.

They are fundamental to life on Earth because of their interaction

with climate and vegetation. Soils provide plants with physical

support as well as nutrients and water for growth. Plants, in turn,

support soils by anchoring them to Earth. Without a vegetative cover,

soil is prone to erosion, which leads to reduced fertility for agricul-

ture and can contribute to famines in the world's poorest nations.

Did you ever play in the dirt as a child? Did you ever stop to

think about where the dirt had come from and how long it had

been there? Although you generally referred to the material as

“dirt,” in all probability you were playing in soil. You may won-

der what difference it makes whether it is called “dirt” or “soil”:

Are they not the same thing? In everyday language the two terms

can be used interchangeably, but in the context of physical geog-

raphy and soil science, the concepts are indeed very different.

The fact is that dirt is not necessarily soil, but soil

forms

in dirt.

Another way to look at it is that soil is what happens to dirt.

Soil

is the uppermost layer of the Earth's surface and con-

tains mineral and organic matter capable of supporting plants

(Figure 11.1). Another way to think about soil is that it is the

outermost rind of Earth, similar to how an orange peel is the

outermost part of the orange. Still another way to consider soil

is as the transition between the atmosphere and the rocky Earth.

Basic Soil Properties

The different variables that, taken together, comprise soil can be

generally classified into the following four groups (Figure 11.2).

1.

Inorganic materials

Inorganic materials are naturally

occurring chemical elements or compounds that possess

a crystalline structure. Each specific mineral (element

or compound) owes its structure to the particular rock

from which it came. Some of the most common miner-

als found in soil contain the elements silicon, aluminum,

iron, calcium, potassium, and magnesium. The element

calcium, for example, is part of the rock limestone. As

limestone disintegrates through a process called

weath-

ering

(discussed in Chapter 14), the minerals become

reduced in size enough for plants to use them as nutrients.

The key point for our present purposes is that, until the

plants absorb the minerals, they are stored in the soil.

2.

Organic matter

Organic matter forms from living and

decayed organisms and accumulates in the upper part of

soil. As plants and animals die and decay, bacteria and fungi

decompose their remains and produce

humus

, which is par-

tially decomposed organic matter. Humus has a sponge-like

quality that allows soil to hold water. In addition, humus

increases soil fertility because (a) it helps stabilize the soil

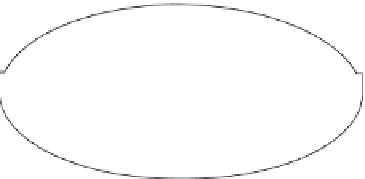

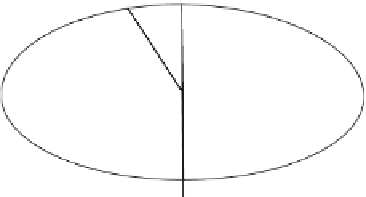

Organic matter (5%)

Pore spaces

(50%)

Mineral

matter (45%)

Includes water

and air

Includes ions and

parent materials

Figure 11.1 Analyzing soil in the field.

Soil scientists investi-

gating a soil profile in a backhoe trench. Understanding soils is an

important part of geography. Many geography students spend at

least some time doing “hands-on” work like this.

Figure 11.2 General composition of soil

Approximately 50%

of soil is mineral and organic matter. The remaining 50% consists

of pore spaces between grains. These spaces hold water and air.

Soil

The uppermost layer of the Earth's surface that forms by

the influence of parent material, climate, relief, and chemical

and biological agents.

Humus

Decomposed organic matter, typically dark, that is

contained within the soil.