Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

15

°

20

°

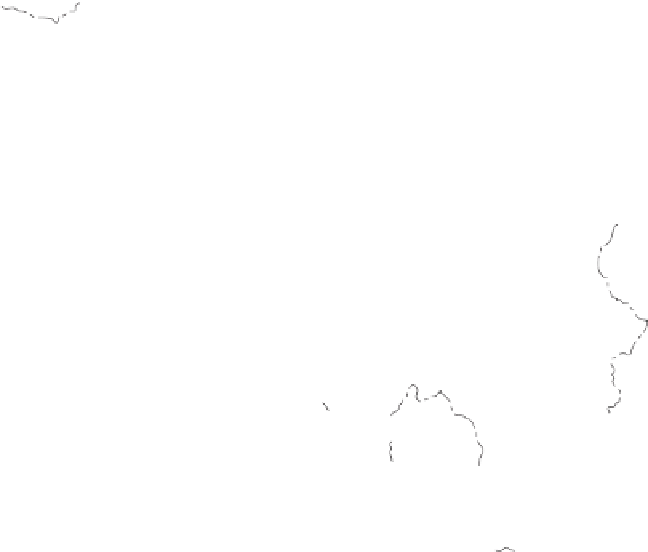

HUNGARY

L

j

ub

lj

ana

Subotica

SLOVENIA

Za

g

reb

ROMANIA

VOJVODINA

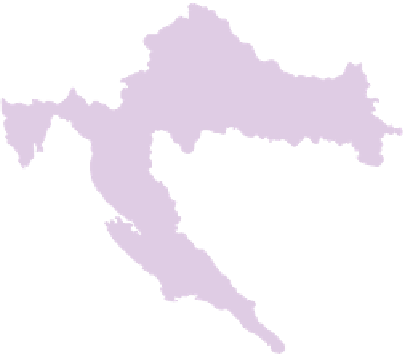

CROATIA

EASTERN

SLAVONIA

Rijeka

Novi Sad

Posavina Corridor

Serb "Republic"

Brcko

Be

lg

rade

Muslim

Domain

Banja Luka

Tuzla

Muslim

Domain

Serb

"Rep."

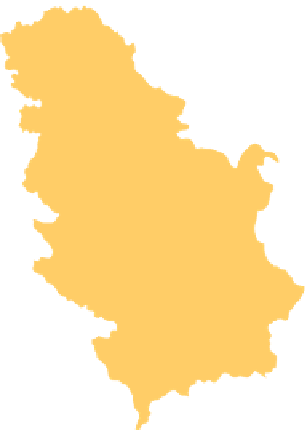

SERBIA

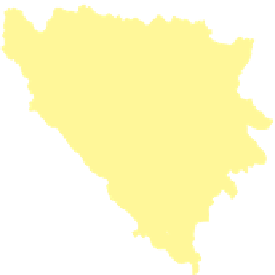

BOSNIA

Sara

j

evo

Pale

Croat

Domain

Serb communities

in Kosovo

Split

Kosovar - Albanian

communities

in Serbia

Mostar

MONTENEGRO

Mitrovica

Niksic

Pristina

Dubrovnik

ITALY

Pec

KOSOVO

Pod

g

orica

BULGARIA

Prizren

Muslim Kosovo

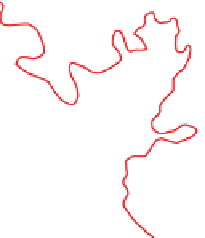

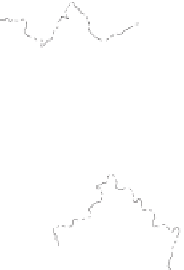

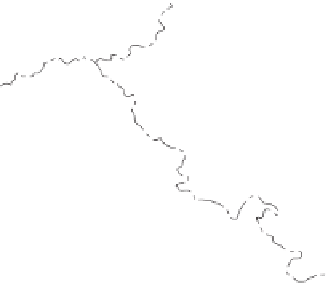

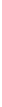

SERBIA AND ITS NEIGHBORS

Skopje

Dayton Accords Partition Line

Muslim Macedonia

MACEDONIA

Muslim-dominated areas

Serb-dominated areas

Tirane

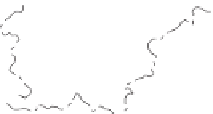

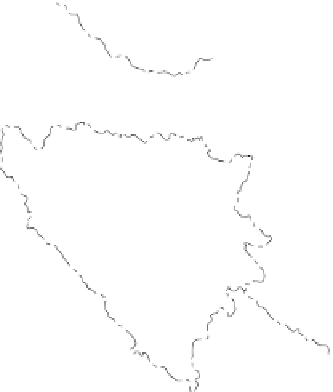

Figure 7.38

Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The map shows

the Muslim-Croat Federation, the Serb

Republic, and the Dayton Accord partition

line.

Durres

National capitals are underlined

ALBANIA

0

0

50

100

150 Kilometers

GREECE

50

100 Miles

Longitude East of Greenwich

20

°

© H. J. de Blij, Power of Place.

Northern Ireland

A number of western European countries, as well as

Canada and the United States, have large Catholic com-

munities and large Protestant communities, and often

these are refl ected in the regional distribution of the pop-

ulation. In most places, the split between these two sects

of Christianity creates little if any rift today. The most

notable exception is Northern Ireland.

Today Northern Ireland and Great Britain

(which includes England, Scotland, and Wales) form

the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern

Ireland (the UK). This was not always the case. For

centuries, the island of Ireland was its own entity,

marked by a mixture of Celtic religious practices and

Roman Catholicism. As early as the 1200s, the English

began to infi ltrate the island of Ireland, taking control

of its agricultural economy. Colonization began in the

sixteenth century, and by 1700, Britain controlled the

entire island. During the 1800s, the Irish colony pro-

duced industrial wealth for Britain in the shipyards

of the north. Protestants from the island of Great

Britain (primarily Scotland) migrated to Ireland dur-

ing the 1700s to Northern Ireland to take advantage of

the political and economic power granted to them in

the colony. During the 1800s, migrants were drawn to

northeastern Ireland where industrial jobs and oppor-

tunities were greatest. During the colonial period, the

British treated the Irish Catholics harshly, taking away

their lands, depriving them of their legal right to own

property or participate in government, and regarding

them as second-class citizens.

In the late 1800s, the Irish began reinvigorating

their Celtic and Irish traditions; this strengthening of

their identity fortifi ed their resolve against the British. In

the early 1900s, the Irish rebelled against British colo-

nialism. The rebellion was successful throughout most of

the island, which was Catholic dominated, leading to the

creation of the Republic of Ireland. But in the 1922 settle-

ment ending the confl ict, Britain retained control of six

counties in the northeast, which had Protestant majori-

ties. These counties constituted Northern Ireland, which

became part of the United Kingdom. The substantial

Catholic minority in Northern Ireland, however, did not

want to be part of the United Kingdom (Fig. 7.39)—par-

ticularly since the Protestant majority, constituting about

two-thirds of the total population (about 1.6 million) of

Northern Ireland, possessed most of the economic and

political advantages.

As time went on, economic stagnation for both

populations worsened the situation, and the Catholics

in particular felt they were being repressed. Terrorist

acts by the Irish Republican Army (IRA), an organi-

zation dedicated to ending British control over all of

Ireland by violent means if necessary, brought British

troops into the area in 1968. Although the Republic of