Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

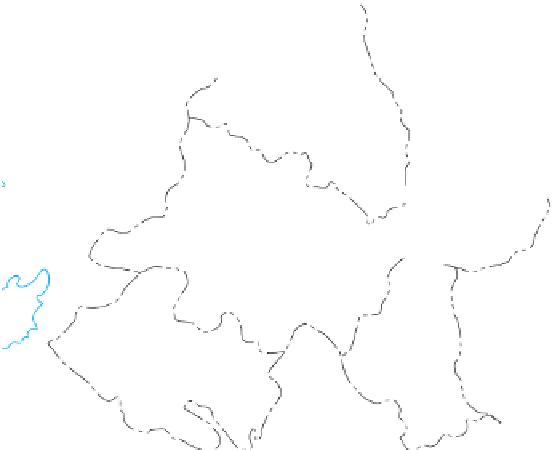

Figure 7.39

Religious Affi liation in Northern Ireland.

Areas of Catholic and Protestant majorities

are scattered throughout Northern Ireland.

Adapted with permission from

: D. G. Pringle,

One Island, Two Nations?

Letchworth: Research

Studies Press/Wiley, 1985, p. 21.

Ireland was sensitive to the plight of Catholics in the

North, no offi cial help was extended to those who were

engaging in violence.

In the face of worsening confl ict, Catholics and

Protestants in Northern Ireland increasingly distanced

their lives and homes from one another. The cultural land-

scape marks the religious confl ict, as each group clusters

in its own neighborhoods and celebrates either important

Catholic or Protestant dates (see Fig. 6.11). Irish geogra-

pher Frederick Boal wrote a seminal work in 1969 on the

Northern Irish in one area of Belfast. Boal used fi eldwork

to mark Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods on a map,

and he interviewed over 400 Protestants and Catholics in

their homes. Boal used the concept of

activity space

to

demonstrate how Protestants and Catholics had each cho-

sen to separate themselves in their rounds of daily activity.

Boal found that each group traveled longer distances to

shop in grocery stores tagged as their respective religion,

walked further to catch a bus in a neighborhood belong-

ing to their own religion, gave their neighborhood differ-

ent toponyms, read different newspapers, and cheered for

different football (soccer) teams.

Although religion is the tag-line by which we refer to

“the Troubles” in Northern Ireland, the confl ict is much

more about nationalism, economics, oppression, access to

opportunities, terror, civil rights, and political infl uence.

But religion and religious history are the banners beneath

which the opposing sides march, and church and cathe-

dral have become symbols of strife rather than peace.

In the 1990s, Boal updated his study of Northern

Ireland and found hope for a resolution. Boal found that

religious identities were actually becoming less intense

among the younger generation and among the more

educated. In Belfast, the major city in Northern Ireland,

Catholics and Protestants are now intermixing in spaces

such as downtown clubs, shopping centers, and college

campuses.

Boal's observations proved to be right, and a move-

ment toward resolution among the population along

with the British government's support for devolution (see

Chapter 8) helped fuel the April 1998 adoption of an Anglo-

Irish peace agreement known as the Belfast Agreement

& Good Friday Agreement, which raised hopes of a new

period of peace in Northern Ireland. Following a decade

of one step forward and two steps back toward peace,

Northern Ireland fi nally realized a tenuous peace in 2007

when the Northern Ireland Assembly (Parliament) was

reinstated. The two sides have made major strides toward

reconciliation in recent years, but the confl ict has not gone

away. While some of the younger generation may be mix-

ing socially, more “peace walls” (giant barriers between

Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods) have been con-

structed since the signing of the Belfast agreement—raising

concerns that segregation may be increasing.